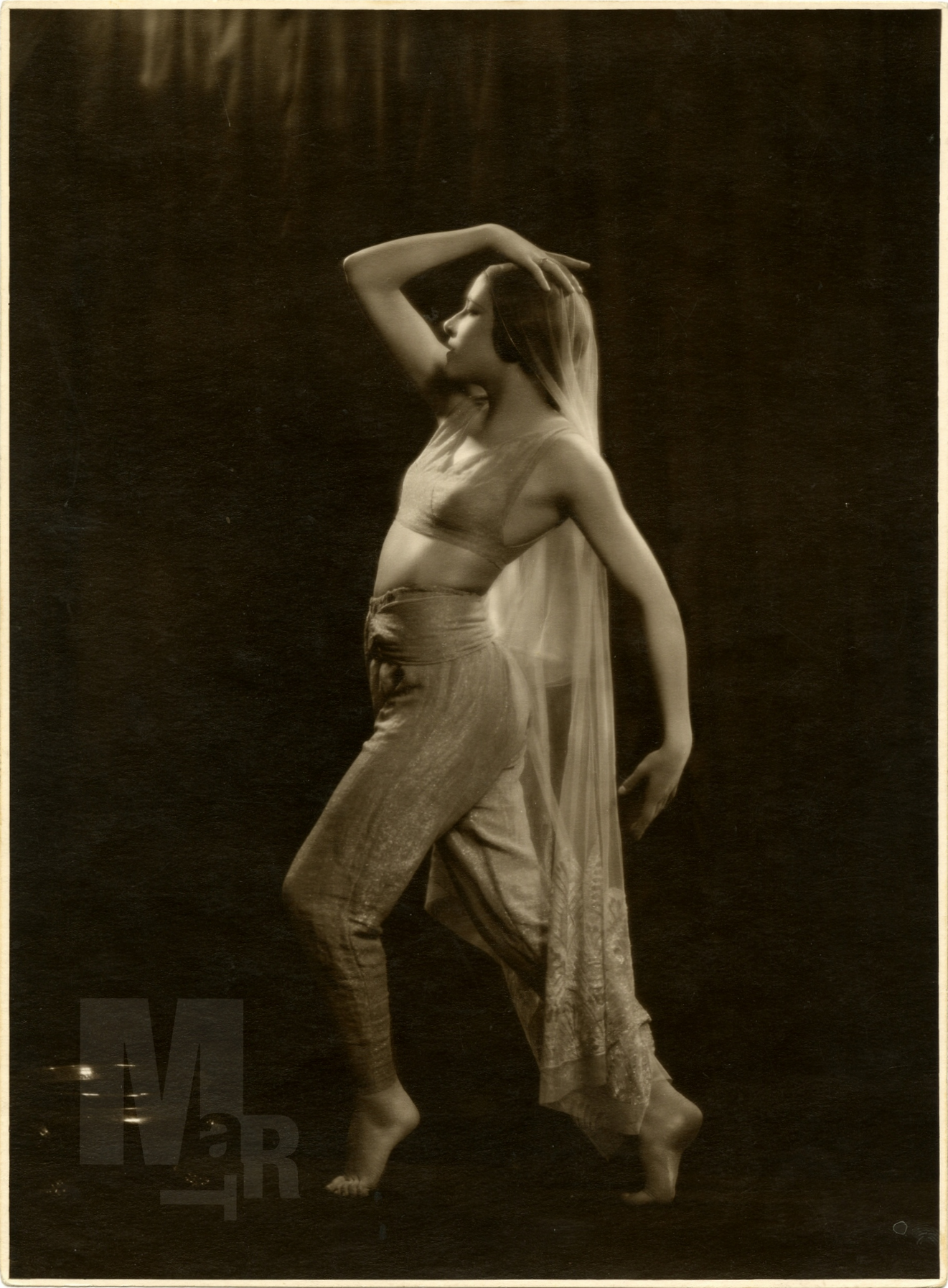

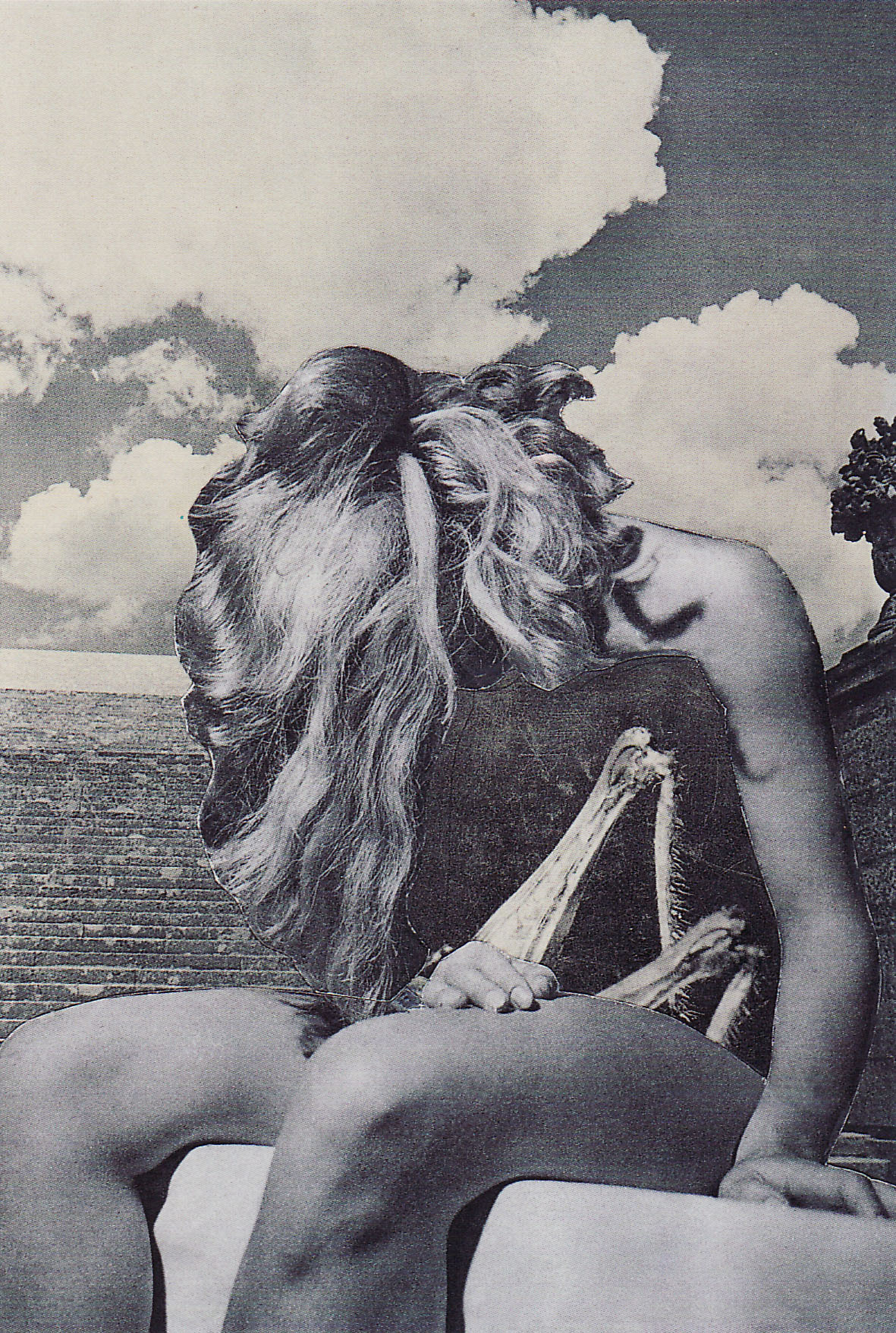

Nude with apples by Drtikol

images that haunt us

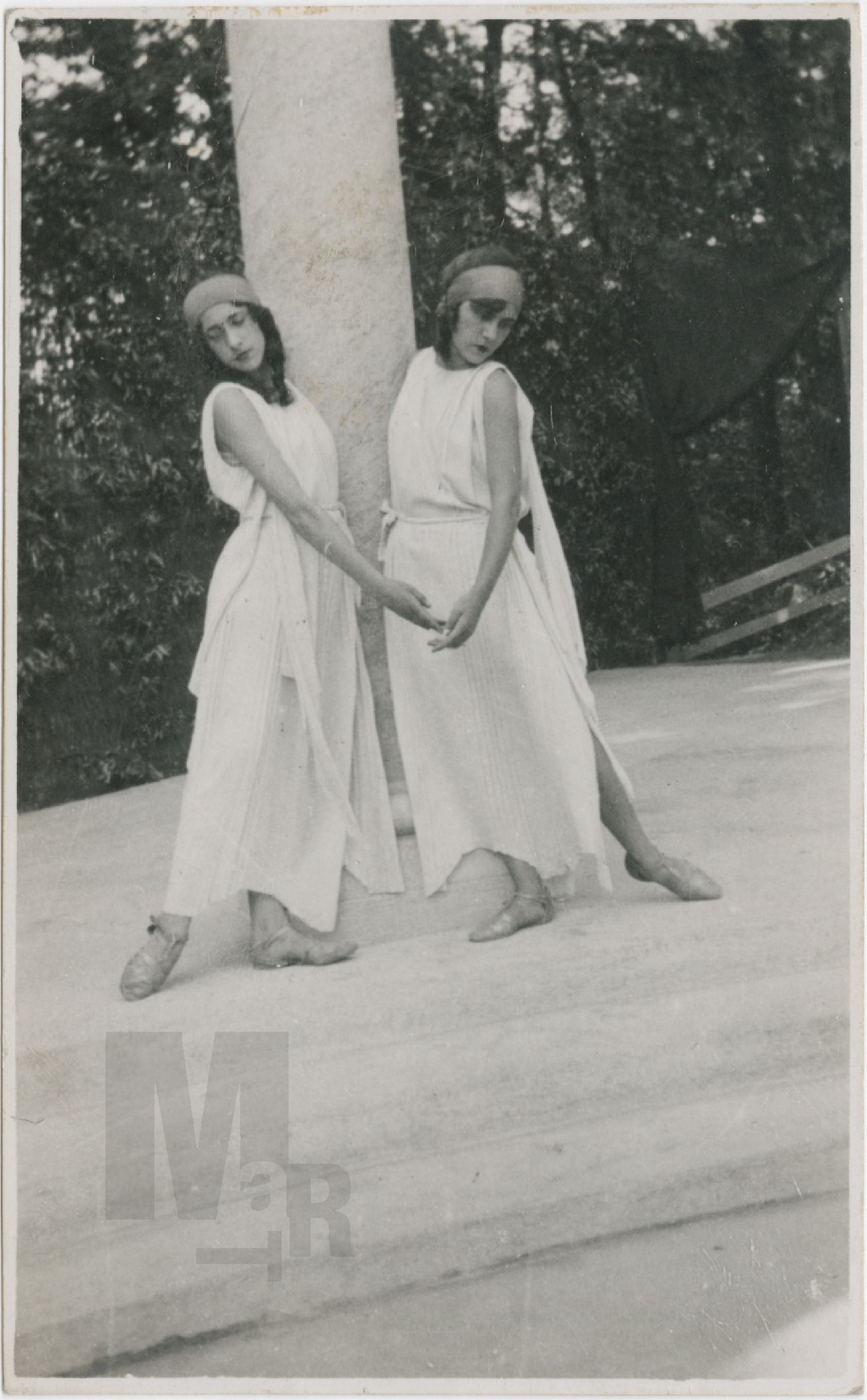

Pubblicata in Vaccarino E., (a cura di) Giannina Censi: danzare il futurismo. Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, 1998 | src & © MART · Fondo Giannina Censi

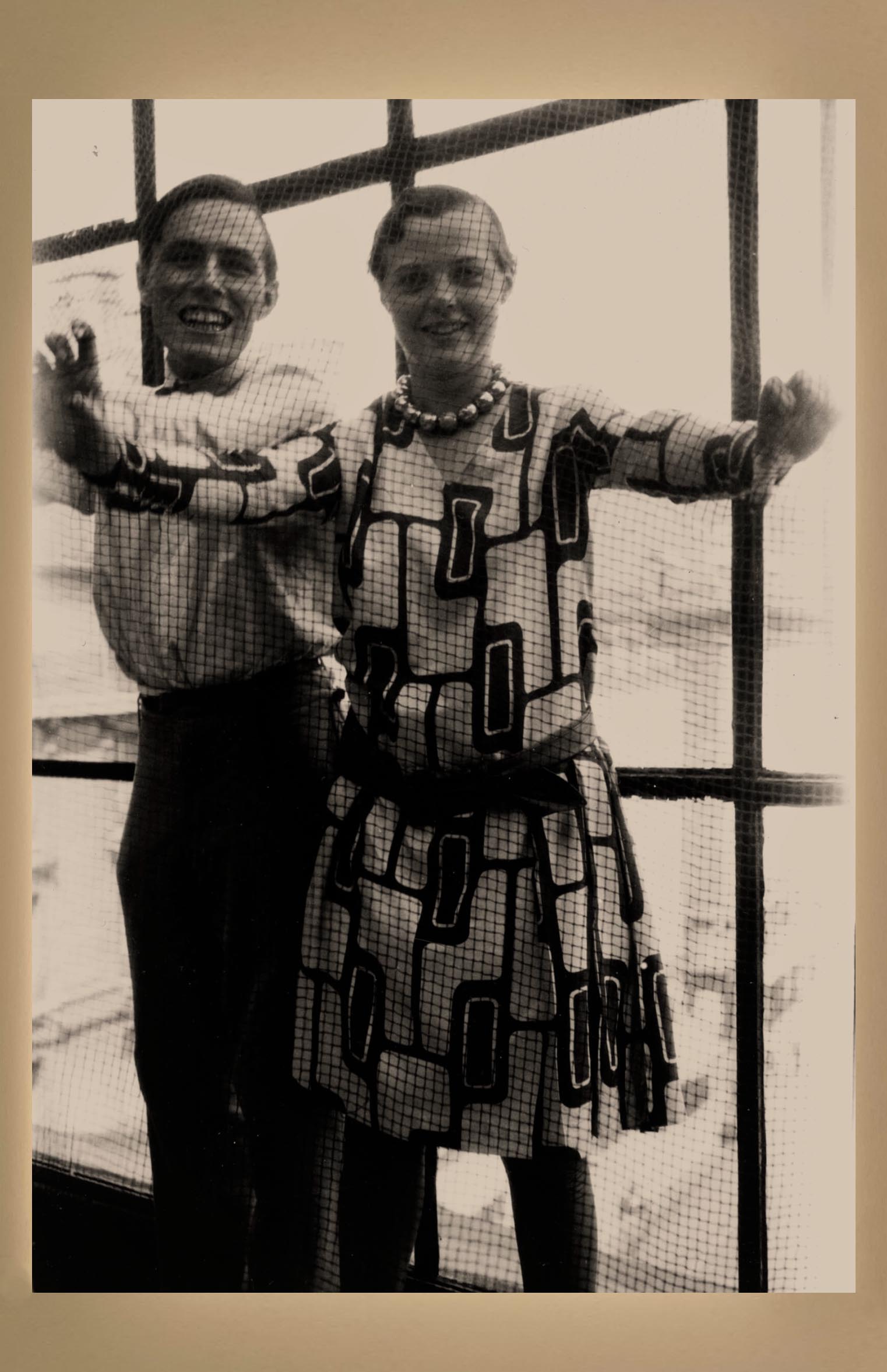

Charlotte Perriand’s ball-bearings necklace was exhibited in 2009 at the exhibition “Bijoux Art Deco et Avant Garde” at the Musee Des Arts Decoratifs in Paris and, in 2011, in the show “Charlotte Perriand 1903-99: From Photography to Interior Design” at the Petit Palais. The necklace became, for a short period, synonymous with Perriand and with her championing of the machine aesthetic in the late 1920s and has subsequently attained the status of a mythical object and symbol of the machine age. This essay considers the necklace as an object and symbol in the context of modernist aesthetics. It also discusses its role in the formation of Perriand’s identity in the late 1920s, when she was working with Le Corbusier, and aspects of gender and politics in the context of the wider modern movement. [more on Semantic Scholar]

“I had a street urchin’s haircut and wore a necklace I made out of cheap chromed copper balls. I called it my ball-bearings necklace, a symbol of my adherence to the twentieth-century machine age. I was proud that my jewelry didn’t rival that of the Queen of England.”

Perriand had asked an artisan with a workshop in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine to make the piece out of lightweight chrome steel balls strung together on a cord. The piece was inspired by Fernand Léger’s still life “Le Mouvement à billes” (1926).

The necklace became a symbol of Perriand’s passion for the mechanical age […] (see also: Charlotte Perriand’s “Ball Bearings” Necklace on Irenebrination)

“Art is in everything,” insisted Charlotte Perriand. […] When you see Charlotte’s chaise longue, chair, and tables in front of that immense Léger, you cannot imagine the design without the art—it is a global vision.

On an adjacent wall, Collier roulement à billes chromées (1927)—a silver choker made from automotive ball bearings that Perriand not only designed but wore—is placed next to a Léger painting, Nature morte (Le mouvement à billes) (Still life [Movement of ball bearings], 1926). [quoted from William Middleton review of the exhibition Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World, on Gagosian]

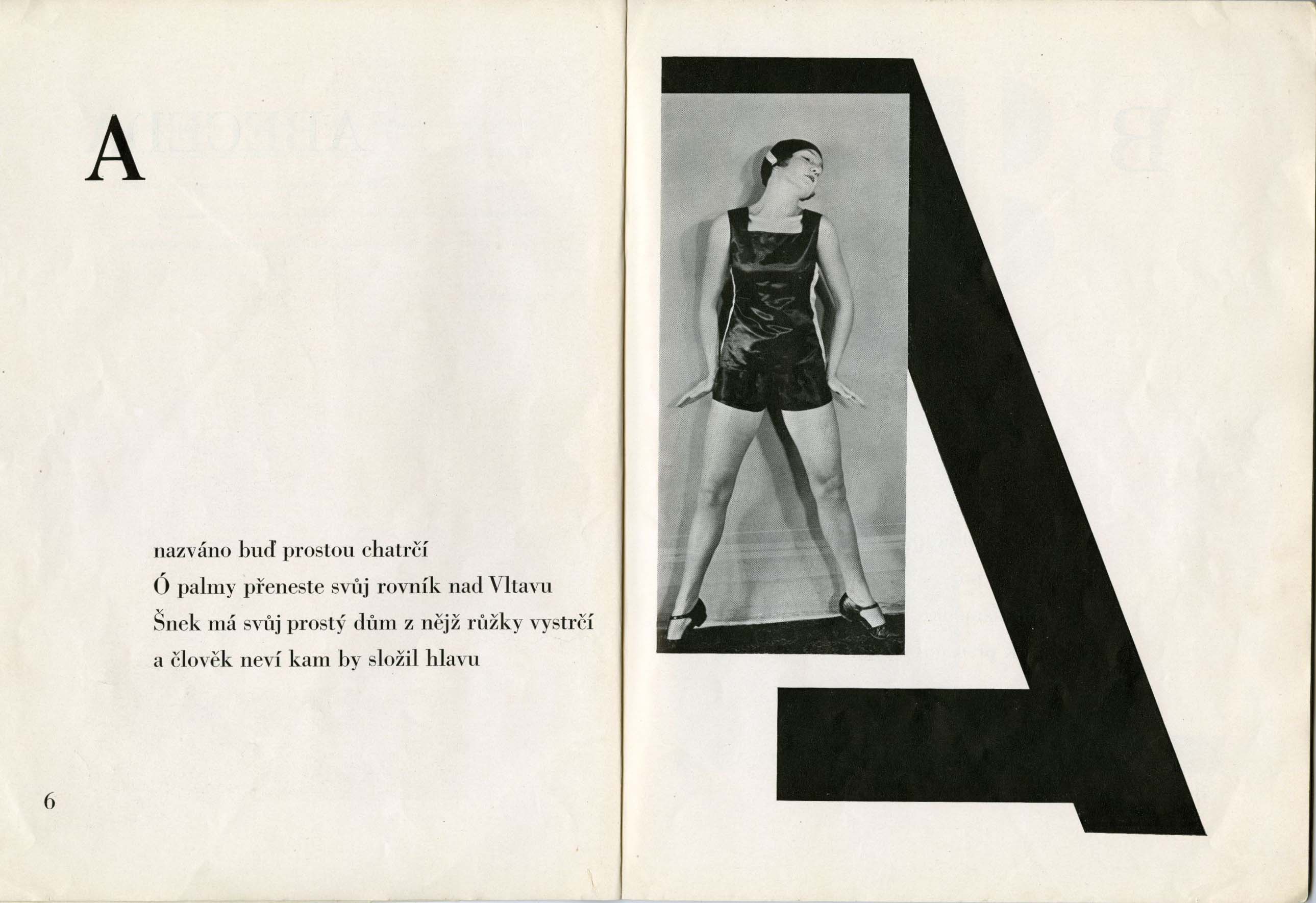

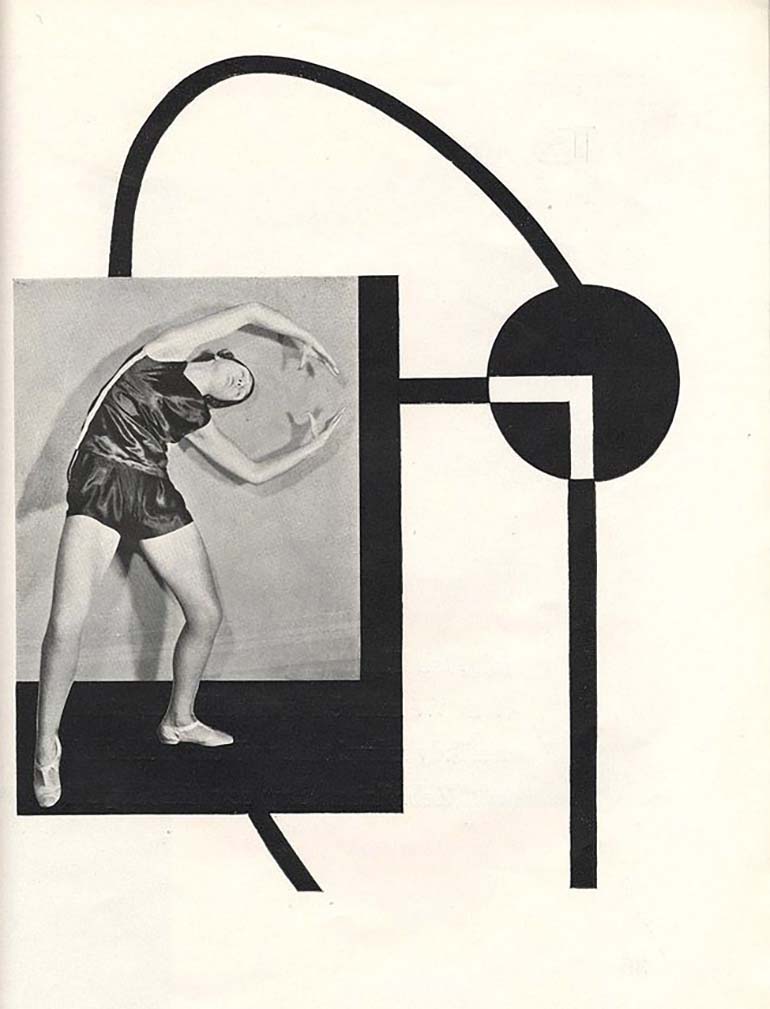

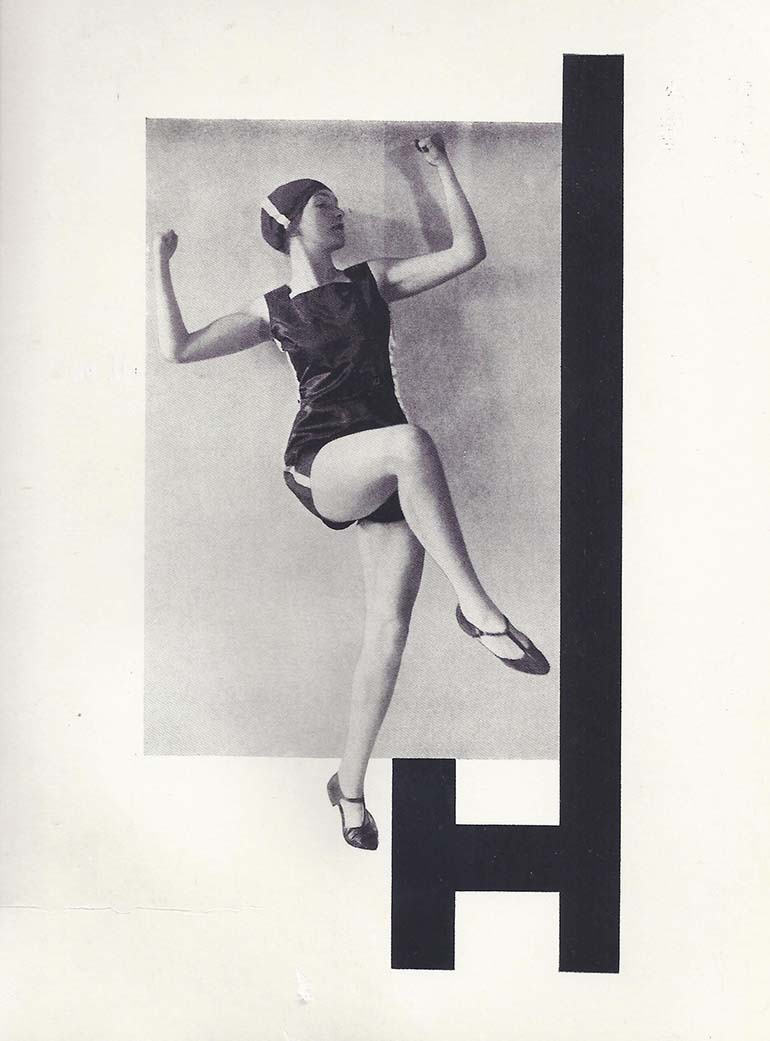

« In Nezval’s Abeceda, a cycle of rhymes based on the shapes of letters, I tried to create a ‹ typofoto › of a purely abstract and poetic nature, setting into graphic poetry what Nezval set into verbal poetry in his verse, both being poems evoking the magic signs of the alphabet. » –Karel Teige, quoted from Abeceda – Index Grafik

In 1926 the Czech dancer Milca Mayerová choreographed the alphabet as a photo-ballet. Each move in the dance is made to the visual counterpoint of Karel Teige’s typographic music. Teige was a constructivist and a surrealist, a poet, collagist, photographer, typographer and architectural theorist, and his 1926 photomontage designs for the alphabet are a uniquely elegant and witty invention, and one of the enduring masterpieces of Czech modernism. –Quoted from The Guardian

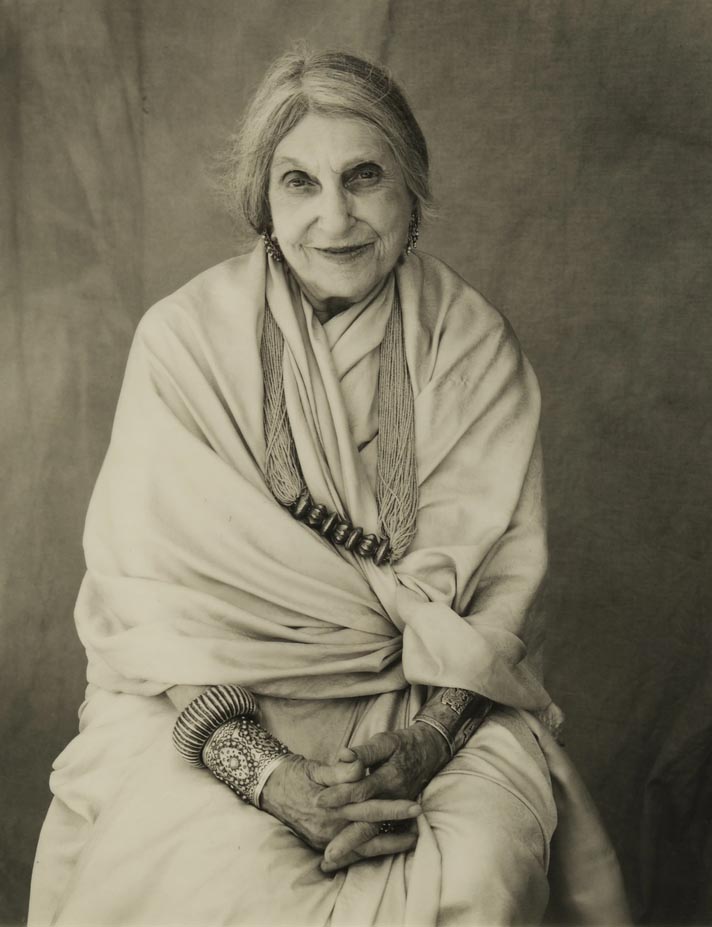

“My life is full of mistakes. They’re like pebbles that make a good road.” ~ Beatrice Wood

“There are three things important in life:

Honesty, which means living free of the cunning mind.

Compassion, because if we have no concern for others, we are monsters.

Curiosity, for if the mind is not searching, it is dull and unresponsive.”

~ Beatrice Wood

Beatrice Wood, aka the “Mama of Dada” was born into a wealthy San Francisco family in 1893. Defying her family’s Victorian values, she moved to France to study theater and art. On the brink of WWI, her parents brought a reluctant Beatrice back to New York, where her mother did everything within her power to discourage her plans for a career on the New York stage. Despite this, Beatrice’s fluency in French led her to join the French National Repertory Theater, where she played over sixty ingénue roles under the stage name “Mademoiselle Patricia” to save her family’s name and reputation.

Wood’s involvement in the Avant-Garde began in these years with her introduction to Marcel Duchamp and later to his friend Henri-Pierre Roché, a diplomat, writer and art collector. Roché, a man fourteen years her senior, joined the duo, becoming creatively (and romantically) entangled. Together they wrote and edited The Blind Man (and the Rongwrong magazine), a magazine that poked the conservative art establishment and helped define the Dada art movement.

Marcel Duchamp brought Beatrice into the world of the New York Dada group, which existed by the patronage of art collectors Walter and Louise Arensberg. The Arensbergs’ home became the center of legendary soirees that included leading figures of the time including Francis Picabia, Mina Loy, Man Ray, Charles Demuth, Joseph Stella, Charles Sheeler and the composer Edgard Varèse.

Beatrice Wood’s career as an artist of note began when she created an abstraction to tease Duchamp that anyone could create modern art. Duchamp was impressed by the work, arranging to have it published in a magazine and inviting her to work in his studio. It was here that she developed her style of spontaneous sketching and painting that continued throughout her life.

Following the formation of the Society of Independent Artists in 1917, Beatrice exhibited work in their Independents exhibition. [text extracted from Wikipedia entry and Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts]

(*) Pubblicata in Vaccarino E., (a cura di) Giannina Censi: danzare il futurismo. Milano: Electa; Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, 1998, p. 15

(**) Pubblicata in Vaccarino E., (a cura di) Giannina Censi: danzare il futurismo. Milano: Electa; Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, 1998, p. 85

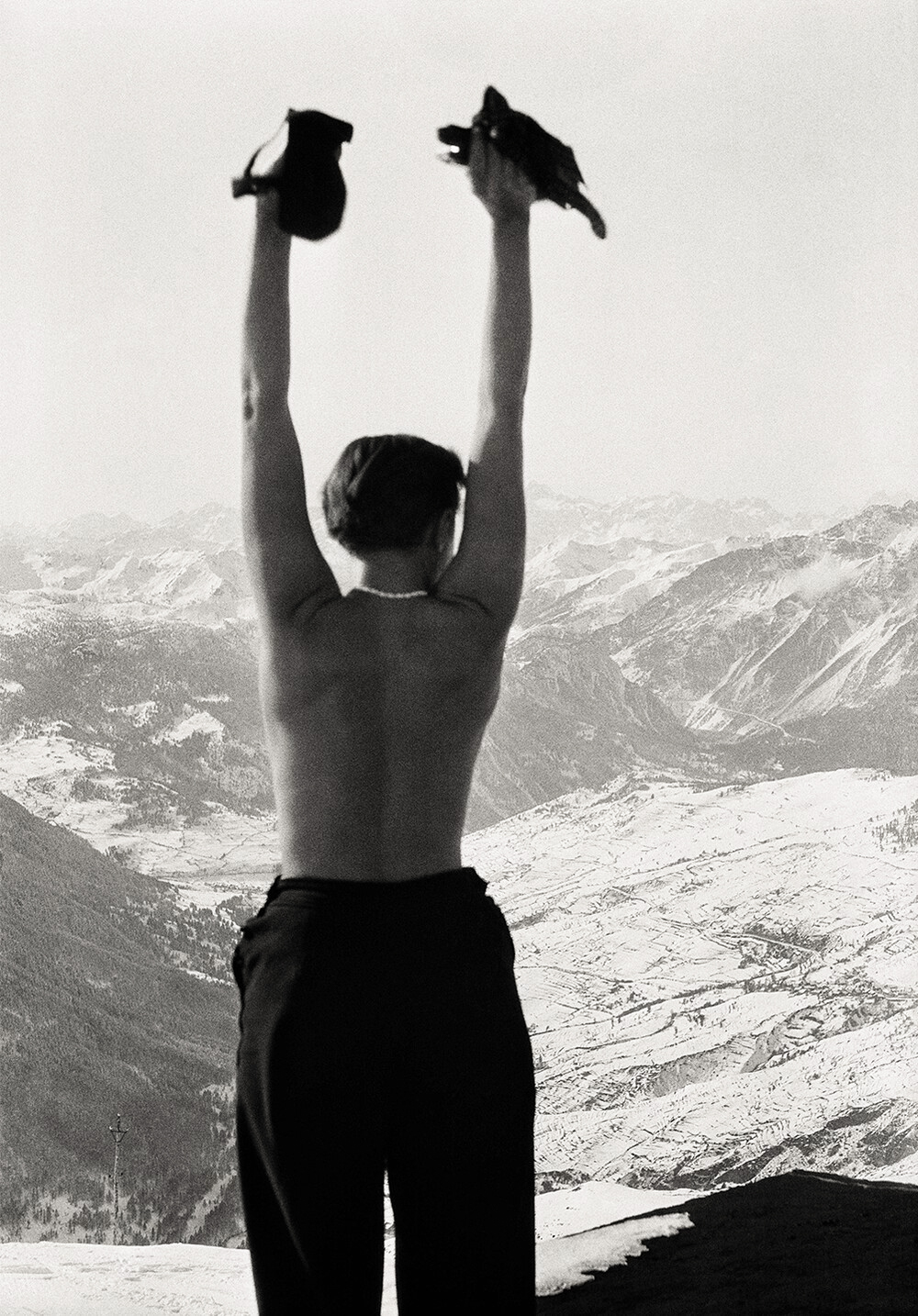

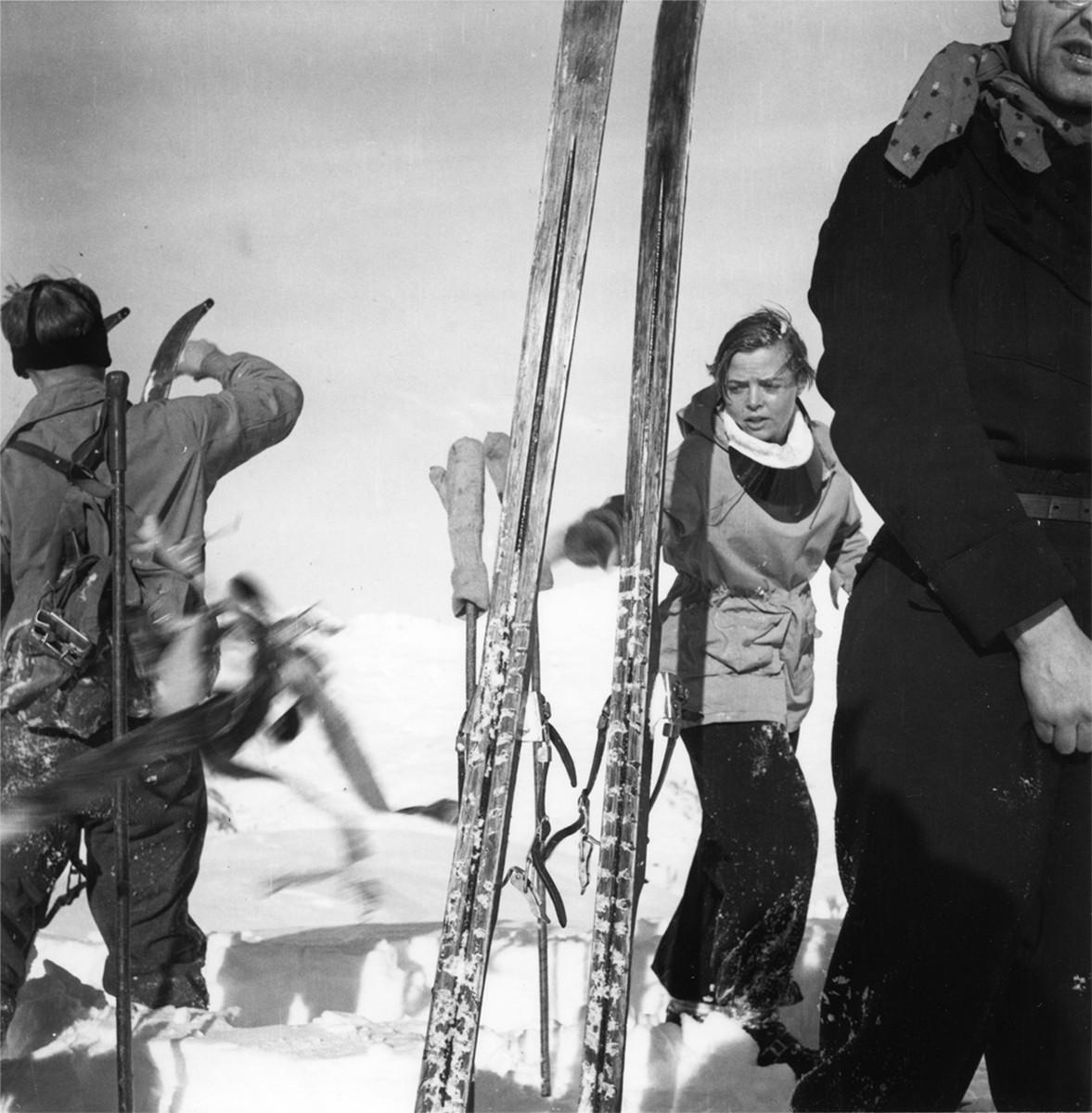

![Giannina Censi all'aria aperta, Plan Maison a 3200 m., 30 luglio 1938 di [Guido Tovo] (1) | src and © Mart ~ Fondo Giannina Censi](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52160045230_13b1f96d9f_o.png)

![Giannina Censi all'aria aperta, Plan Maison a 3200 m., 30 luglio 1938 di [Guido Tovo]. In verso nota ms. "Dal Plan Maison 3200 metri, luglio 1938" (2)](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52159793959_4e87e900f0_o.png)

(1) e (2) Pubblicata in Vaccarino E., (a cura di) Giannina Censi: danzare il futurismo. Milano: Electa; Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, 1998, pp. 50-51

(1) e (3) Pubblicata in Belli G. (a cura di), Sprachen des Futurismus, Berlin: Berliner Festspiele- Martin Gropius Bau, 2009, p. 243

(3) Pubblicata in Bonfanti E., Il corpo intelligente. Torino: il segnalibro, 1995, p. 51