images that haunt us

Faces. The power of the human visage (2021)

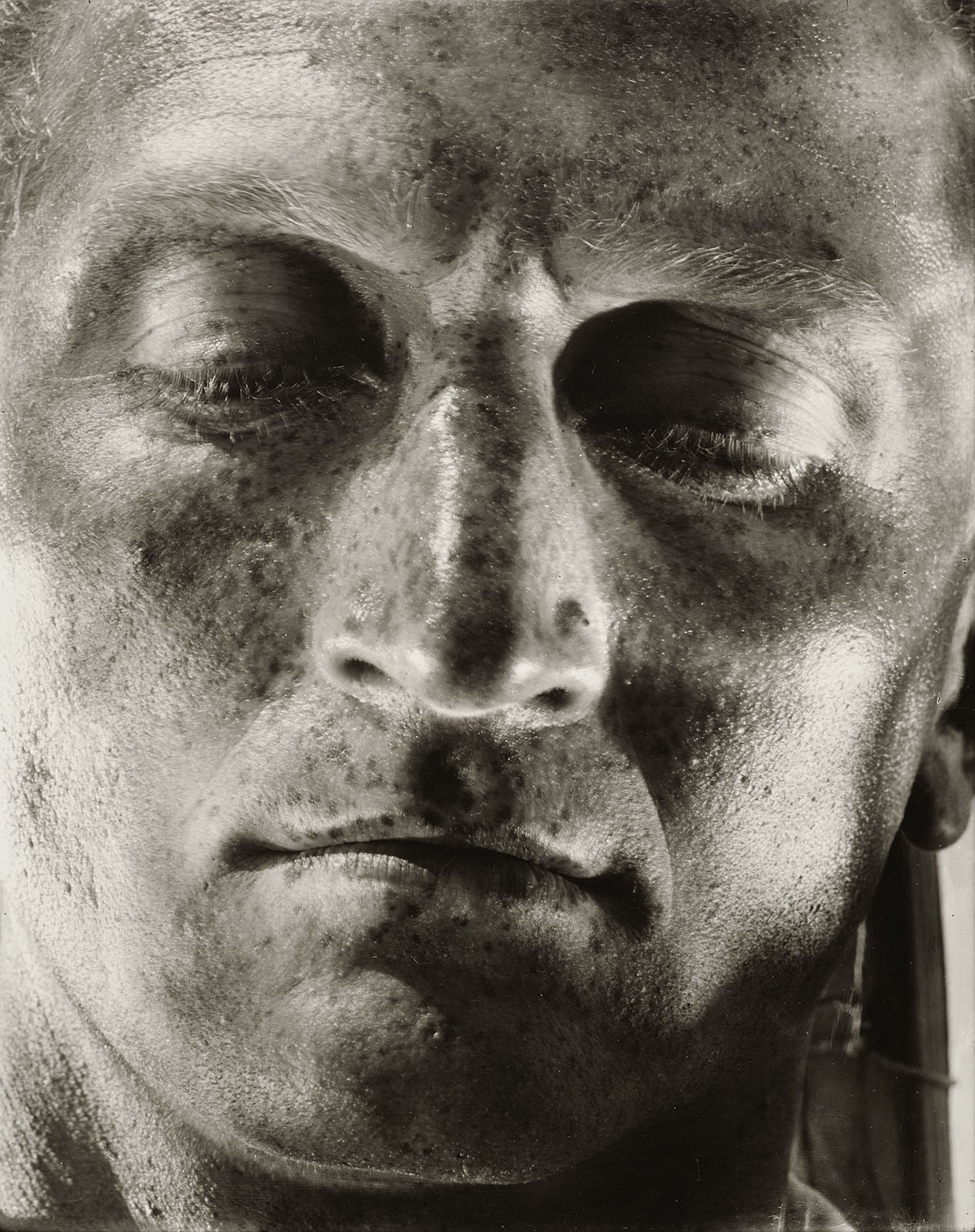

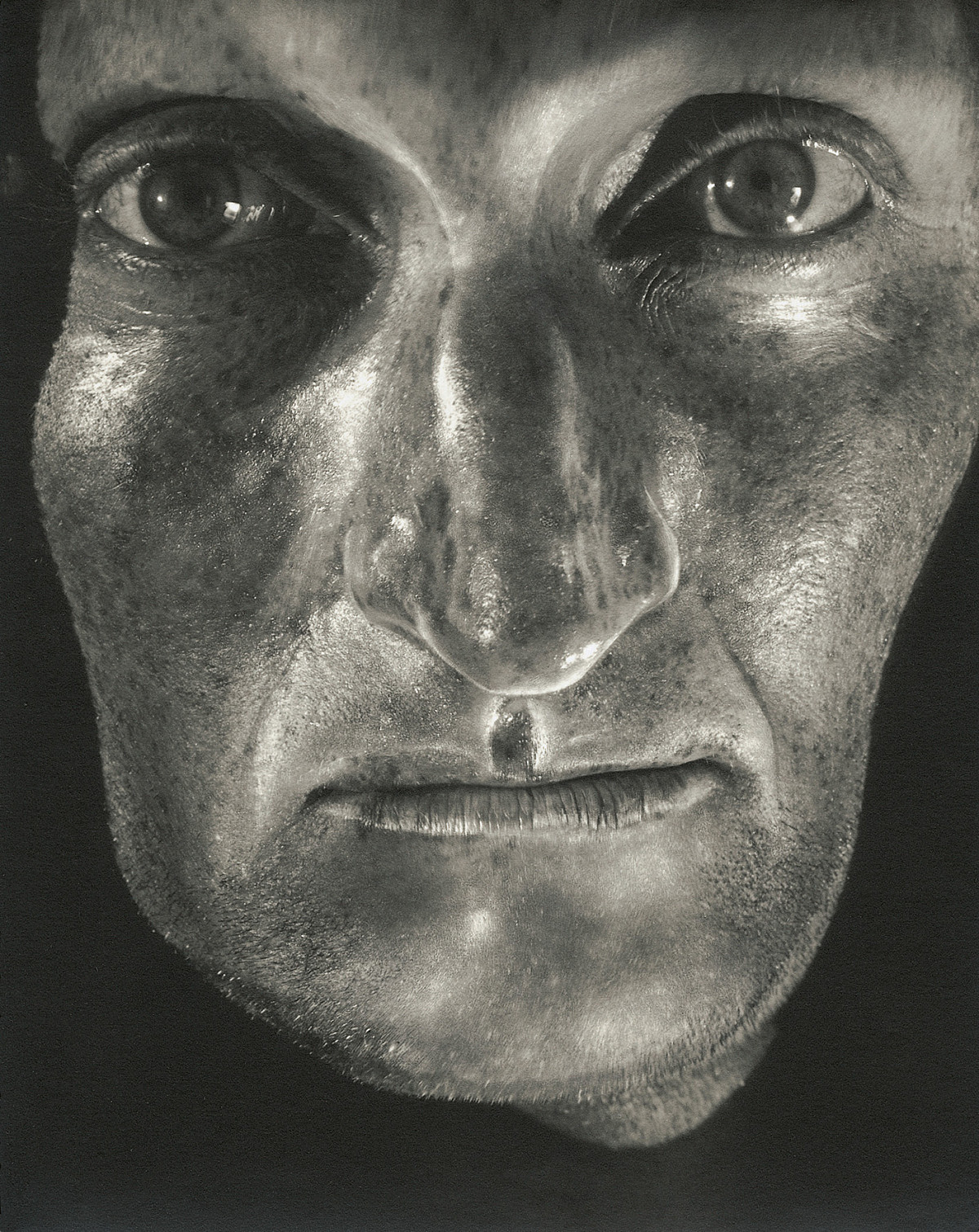

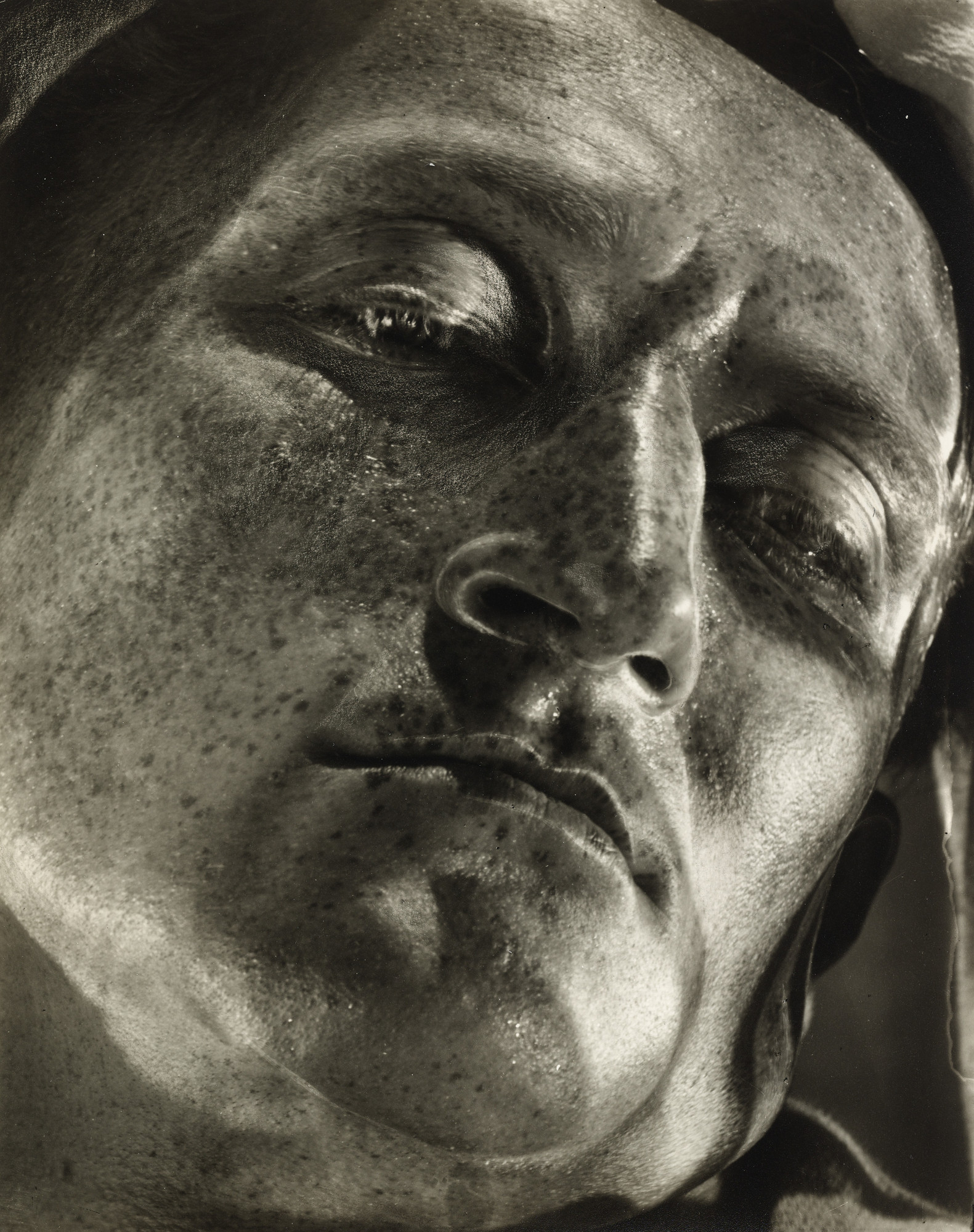

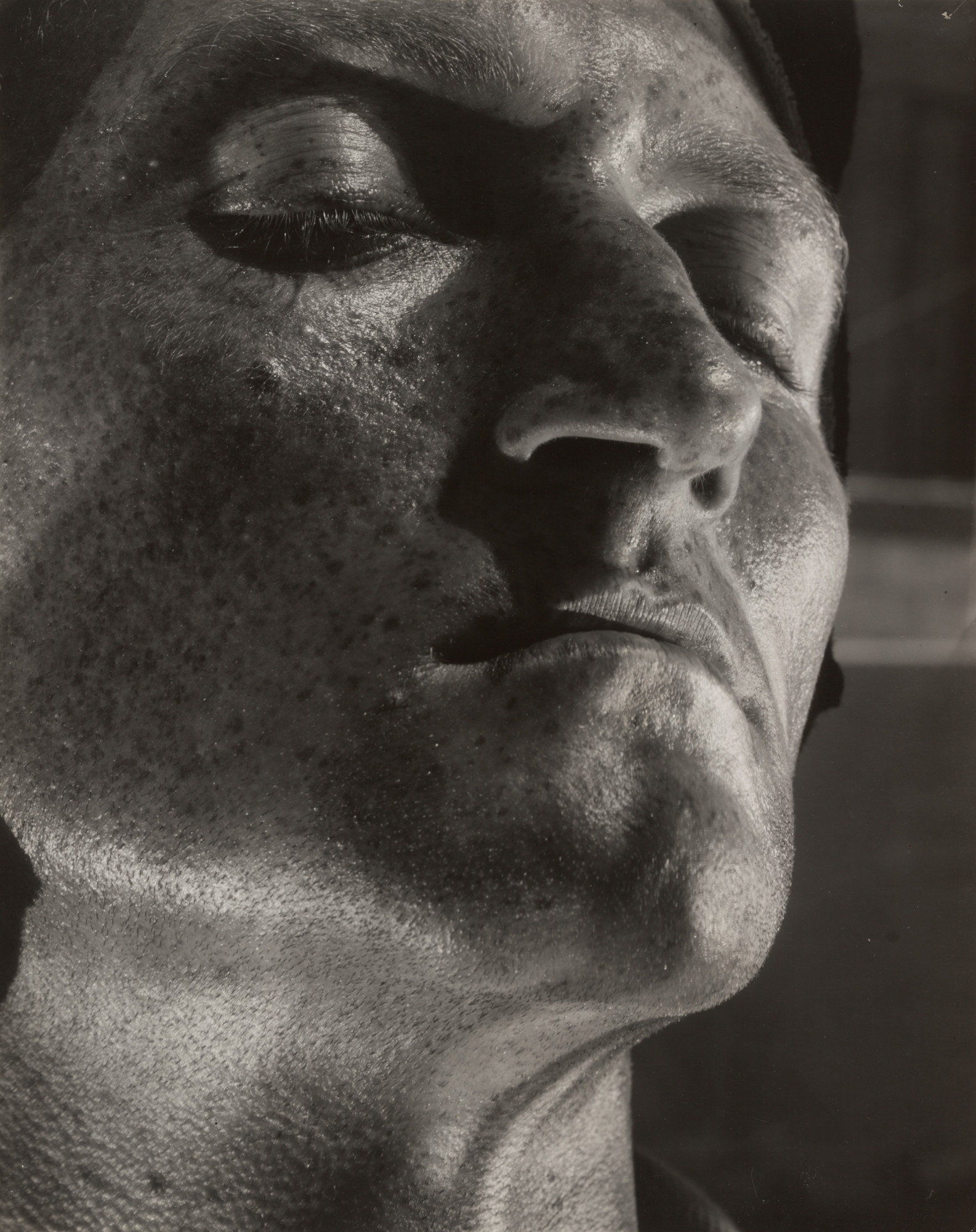

Starting from Helmar Lerski’s outstanding photo series Metamorphosis through Light (1935/36), the exhibition Faces presents portraits from the period of the Weimar Republic.

The 1920s and ’30s saw photographers radically renew the conventional understanding of the classic portrait: their aim was no longer to represent an individual’s personality; instead, they conceived of the face as material to be staged according to their own ideas. In this, the photographed face became a locus for dealing with avant-garde aesthetic ideas as well as interwar-period social developments. And it was thus that modernist experiments, the relationship between individual and general type, feminist roll-playing, and political ideologies collided in—and thereby expanded—the general understanding of portrait photography.

Faces. Die Macht des Gesichts (2021)

Die Ausstellung Faces in der ALBERTINA präsentiert Porträts der deutschen Zwischenkriegszeit. Ausgangspunkt dafür ist Helmar Lerskis herausragende Fotoserie Verwandlungen durch Licht (1935/36).

In den 1920er- und 30er-Jahren erneuern Fotografinnen und Fotografen das Verständnis des klassischen Porträts radikal: Ihre Aufnahmen dienen nicht mehr der Darstellung der Persönlichkeit eines Menschen, sondern fassen das Gesicht als nach ihren Vorstellungen inszenierbares Material auf.

Über das fotografierte Gesicht werden sowohl ästhetische Überlegungen der Avantgarde als auch gesellschaftliche Entwicklungen der Zwischenkriegszeit dargestellt. Experimente mit neuer Formensprache, das Verhältnis zwischen Individuum und Typ, feministische Rollenspiele und politische Ideologien treffen aufeinander und erweitern damit das Verständnis der Porträtfotografie.

Quelle : Albertina Museum

![Aenne Biermann :: Orchid, ca. 1930. Gelatin silver print. [Detail] From : Aenne Biermann : Up Close and Personal at Tel Aviv Museum of Art](https://unregardobliquehome.files.wordpress.com/2023/01/aenne-biermann_orchid-ca.-1930-detail-tel-aviv-museum.jpg)

![Aenne Biermann (1898-1933) :: Kaktus, [Cactus], around 1929, © Museum Ludwig, Köln](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52626356372_254b3ddb72_o.jpg)

Aenne Biermann zeigte, wie viel Poesie in unscheinbaren Dingen stecken kann

Die deutsche Fotografin Aenne Biermann begann als Autodidaktin mit der Geburt ihrer Kinder zu fotografieren. Auch wenn sie das Alltägliche abbildete, banal sind ihre Arbeiten keineswegs.

Aenne Biermann (1898-1933) wurde als Tochter einer wohlhabenden jüdisch-deutschen Familie geboren. Mit der Geburt ihrer Kinder begann sie ohne künstlerische Ausbildung als Autodidaktin zu fotografieren. Sie fotografierte zunächst in ihrer häuslichen Umgebung – oft ihre Kinder. Aber auch Landschaften, Architekturdetails und Stillleben gehörten seit den Anfängen zum fotografischen Oeuvre der Künstlerin.

Die Fotografin arbeitete sich in ihrer nur 13-jährigen dauernden Schaffenszeit an ihrer unmittelbaren Umgebung ab (welche in Gera war) und vergrösserte ihren Radius bis Paris. Mit Ausweitung ihres Radius’ erweiterte sich auch ihre Arbeitsweise – Akt- und Stadtaufnahmen von Paris ergänzten ihr späteres Werk.

Betrachtet man ihre Bilder, ist es so, als ob man eine zweite Chance bekäme, das Banal-Alltägliche neu zu sehen. Die Arbeiten zeigen Früchte, Pflanzen, das Innenleben einer Schublade, Eier, Steine, Krimskrams, Gleise, das Innere eines Klaviers, Kindergesichter oder Körper.

Die Fotografin muss in einer Art Unermüdlichkeit und Konzentriertheit das sie Umgebende auf Schönheit und Stimmung abgetastet haben. Baumnüsse in einer Papiertüte oder Äpfel auf einem Teller, alles ist einem vertraut. Und doch sind ihre Werke durch das Spiel mit Perspektiven, Ausschnitt, Kontrast und Licht einzigartig und voll Poesie. Ihre Arbeiten haben etwas Beruhigendes an sich und könnten den gestressten, von reizüberfluteten Jetztlern ein neues Sehen beibringen.

Ob der klaren Schönheit und Pointierung gerät man beinah in eine Art kontemplative Verzückung und beginnt, die Dinge, die Landschaften, die Personen neu, anders oder wahrhaftig zu sehen. Diese sensible, unaufgeregte, aber auch sehr konkrete Eigenschaft ihrer Bilder führte dazu, dass sie zu einer der wichtigsten Vertreterinnen der Avantgardefotografie der 1920er und 1930er Jahre wurde.

Der Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess hat jüngst unter dem Titel «Aenne Biermman: Up close and personal» in Kooperation mit dem Tel Aviv Museum of Art eine Publikation veröffentlicht, die mit 100 Abbildungen und mehreren Essays Biermanns Schaffen umfassend beschreiben. Die Publikation begleitet die Anfangs August 2021 eröffnete Ausstellung in Tel Aviv.

Aenne Biermann showed how much poetry can be found in inconspicuous things

The German photographer Aenne Biermann started as an autodidact with the birth of her children. Even if she depicts the everyday, her works are by no means banal.

Aenne Biermann (1898-1933) was born into a wealthy Jewish-German family. With the birth of her children, she began to photograph as an autodidact without any artistic training. She initially photographed in her home environment – often her children. But landscapes, architectural details and still-lifes have also been part of the artist’s photographic oeuvre from the very beginning.

During her creative period of only 13 years, the photographer worked on her immediate environment (which was in Gera) and extended her radius to Paris. As her radius expanded, so did her way of working – nude and city photographs of Paris complemented her later work.

Looking at her paintings is like getting a second chance to see the mundane everyday in a new way. The works show fruits, plants, the inner workings of a drawer, eggs, stones, odds and ends, rails, the inside of a piano, children’s faces or bodies.

The photographer must have scanned her surroundings for beauty and mood with a kind of tirelessness and concentration. Tree nuts in a paper bag or apples on a plate, everything is familiar. And yet her works are unique and full of poetry through the play with perspective, detail, contrast and light. There’s something calming about her work, and it could teach the stressed, overstimulated now-people a new way of seeing.

Because of the clear beauty and emphasis, one almost falls into a kind of contemplative rapture and begins to see the things, the landscapes, the people in a new, different or truthful way. This sensitive, calm, but also very concrete quality of her pictures made her one of the most important representatives of avant-garde photography of the 1920s and 1930s.

The publishing house Scheidegger & Spiess recently published a publication entitled “Aenne Biermman: Up close and personal” in cooperation with the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, which comprehensively describes Biermann’s work with 100 illustrations and several essays. The publication accompanies the exhibition that opened in Tel Aviv at the beginning of August 2021.

Quoted from Bellevue (NZZ)

About the Work

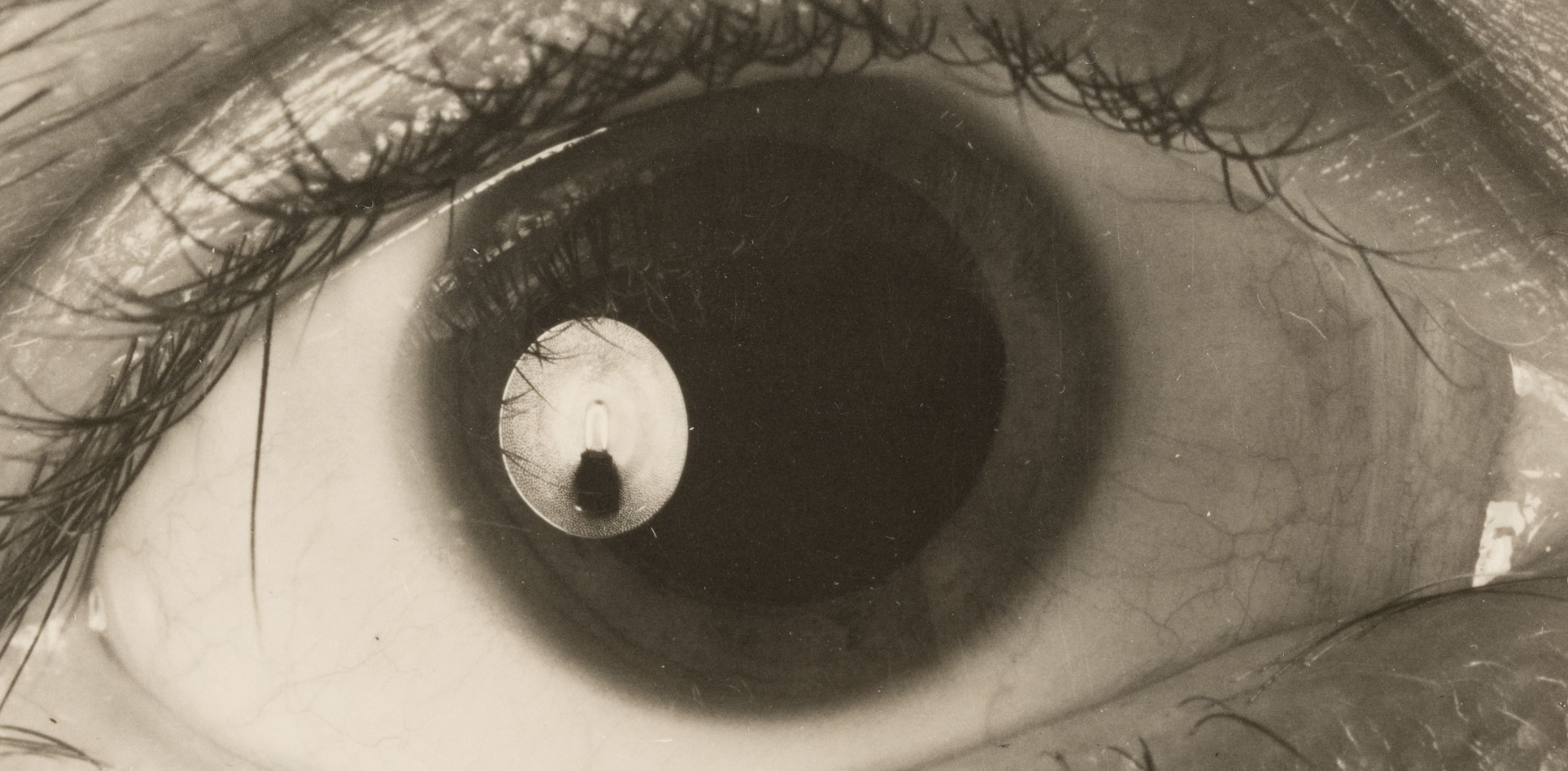

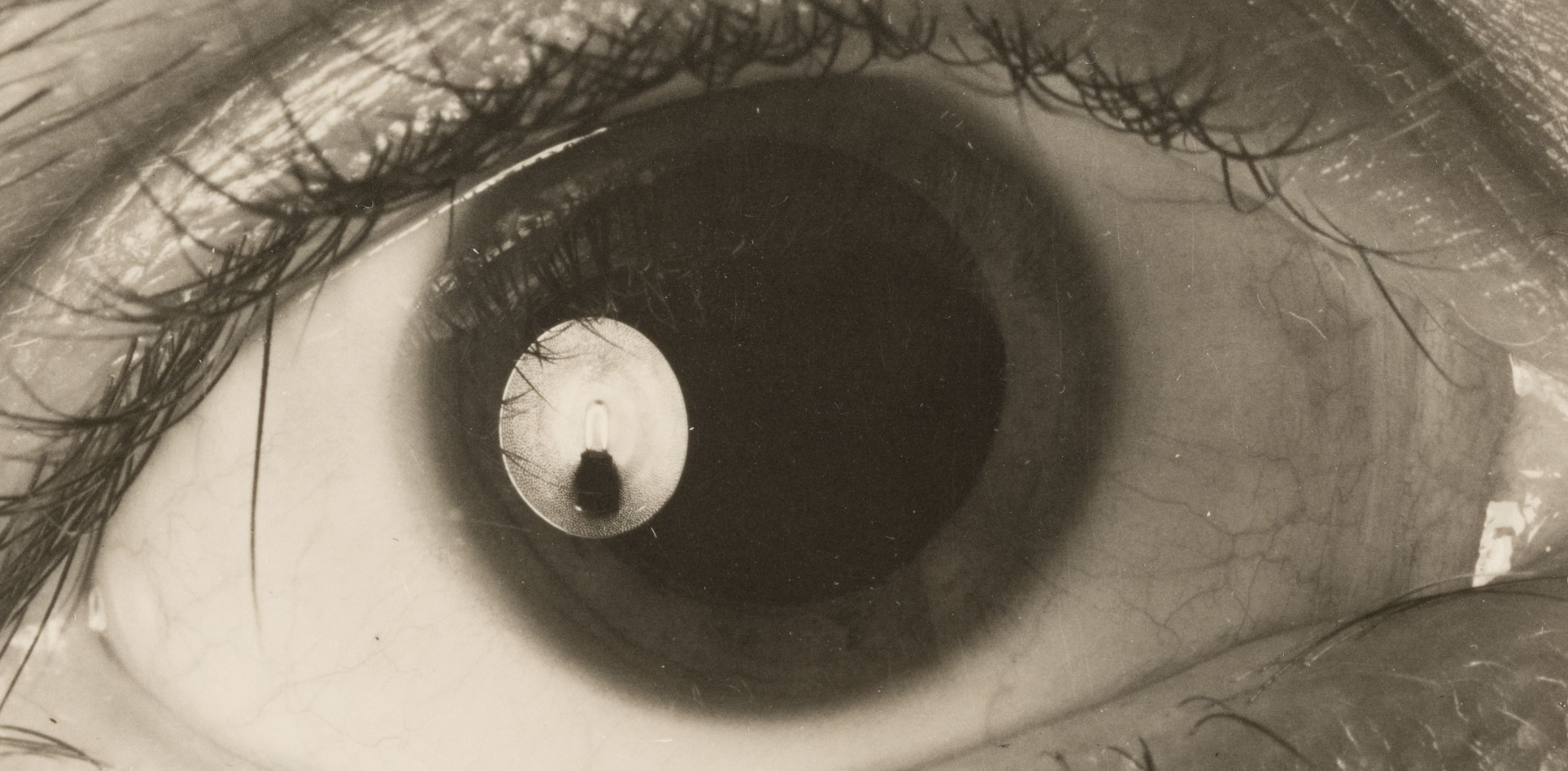

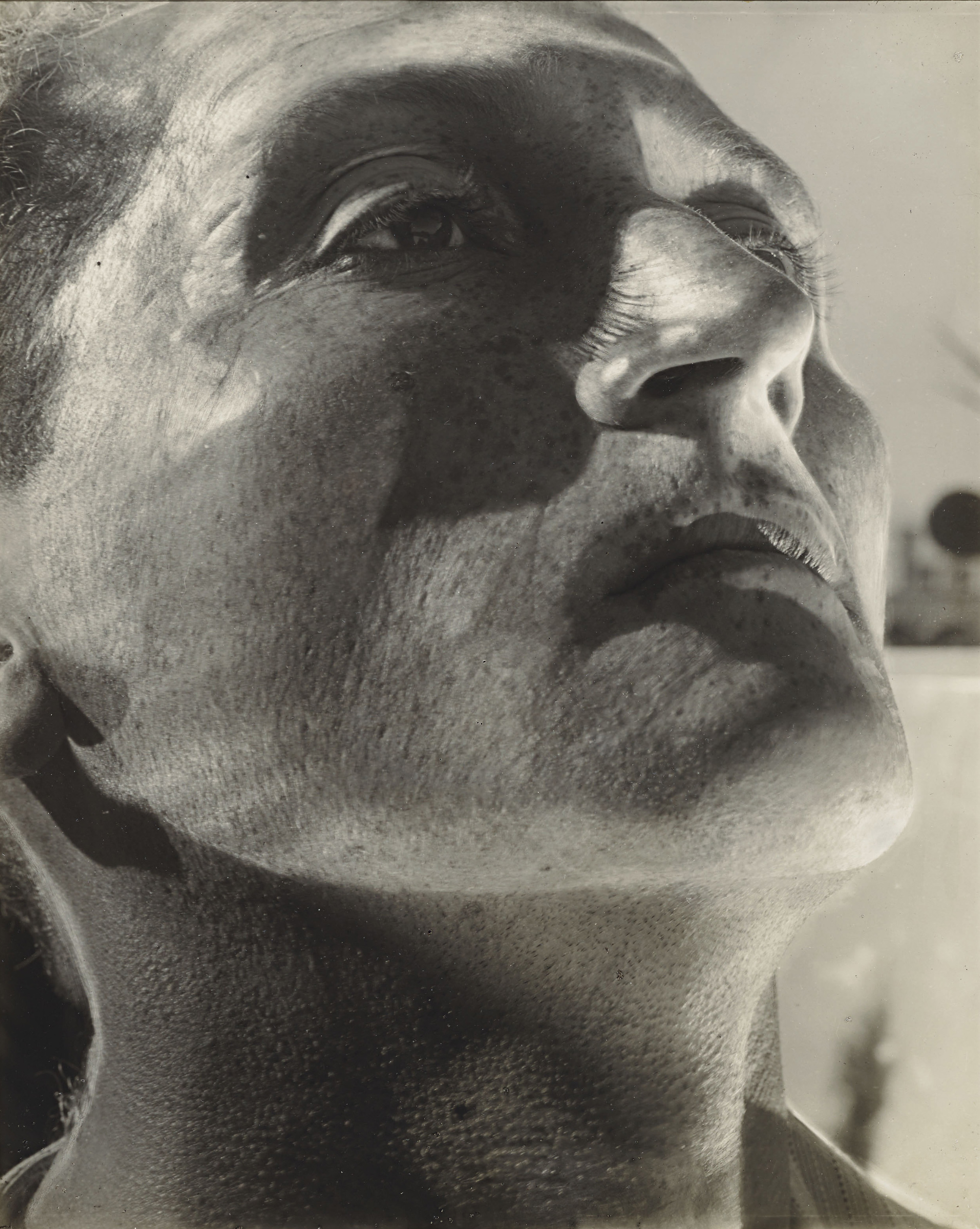

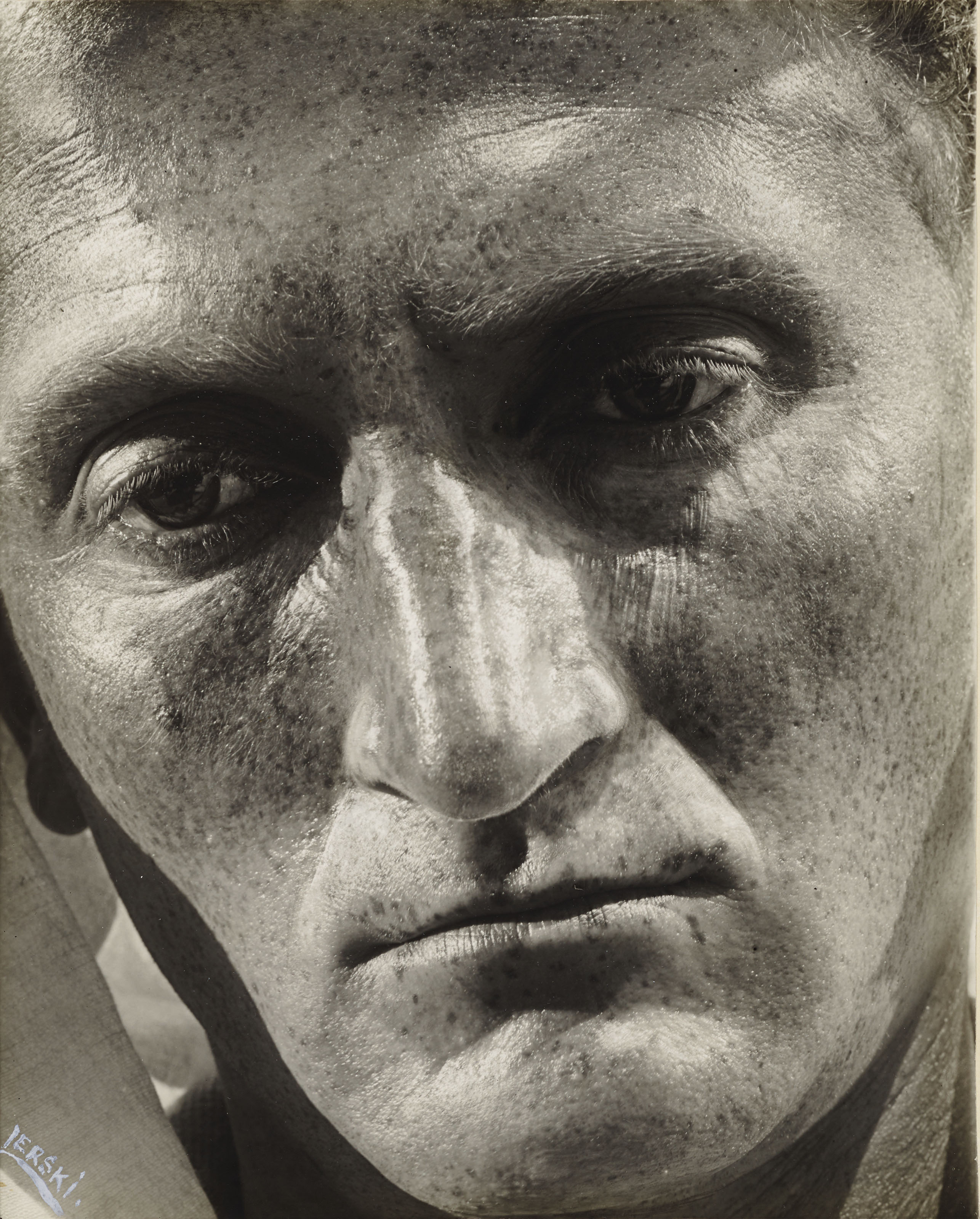

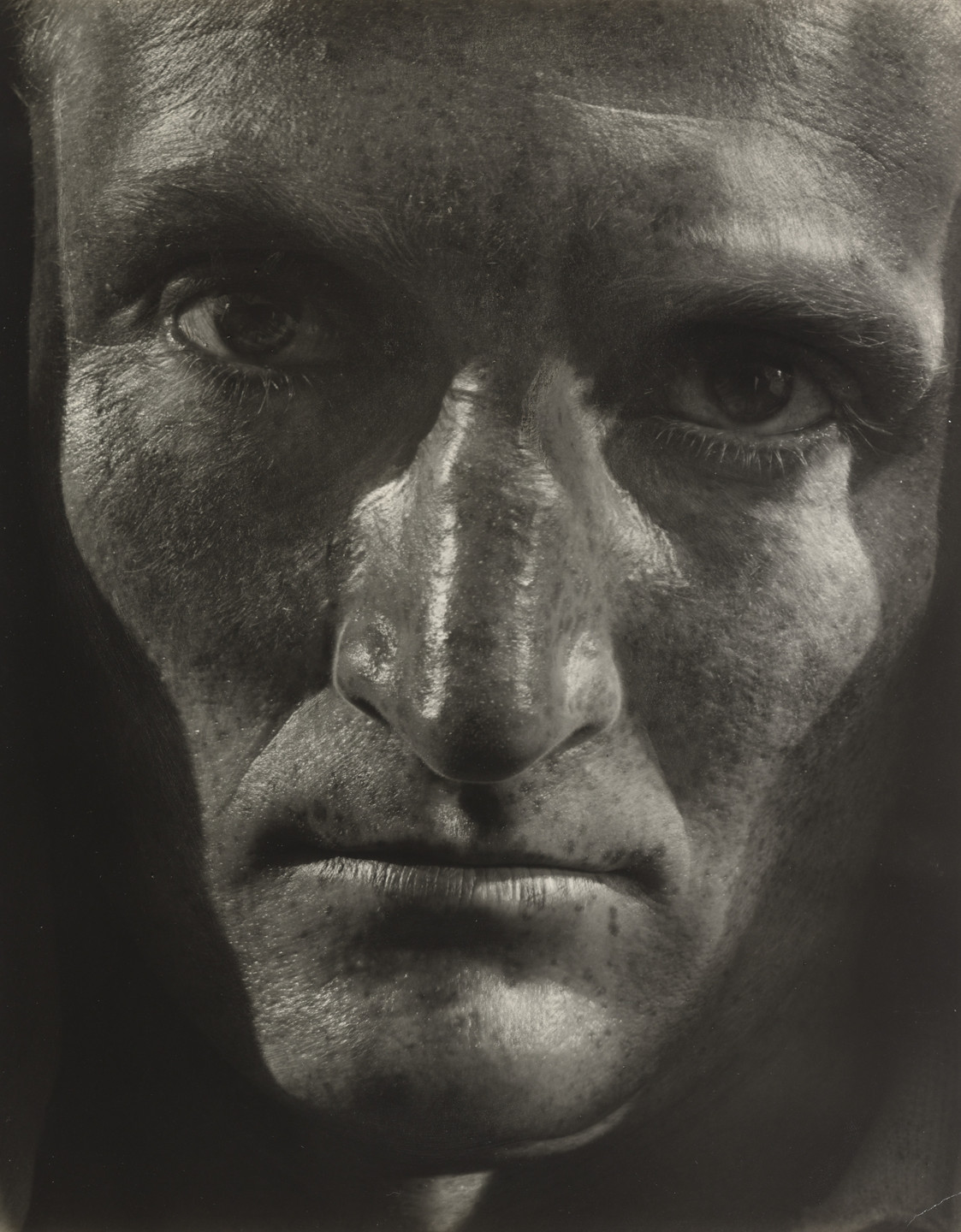

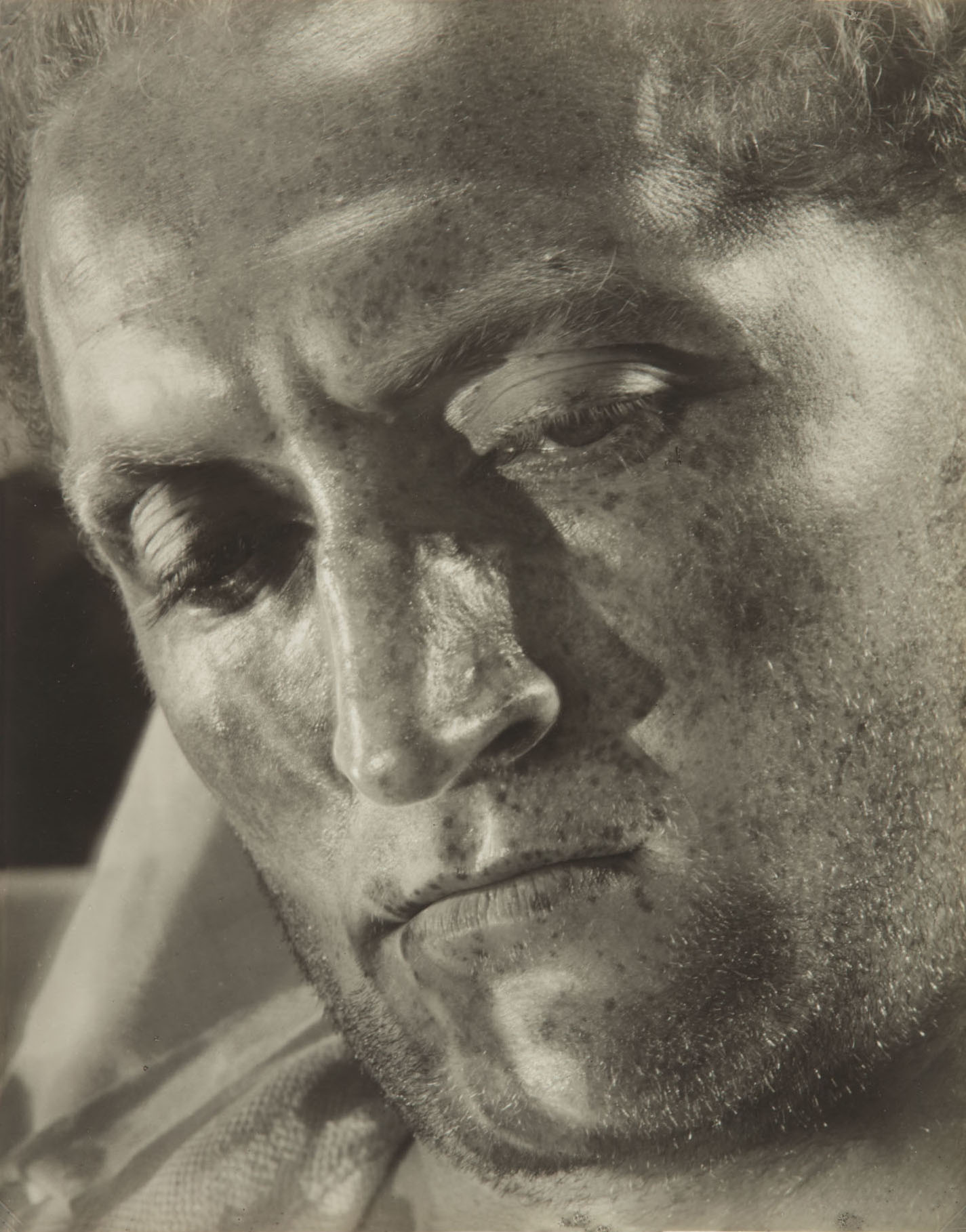

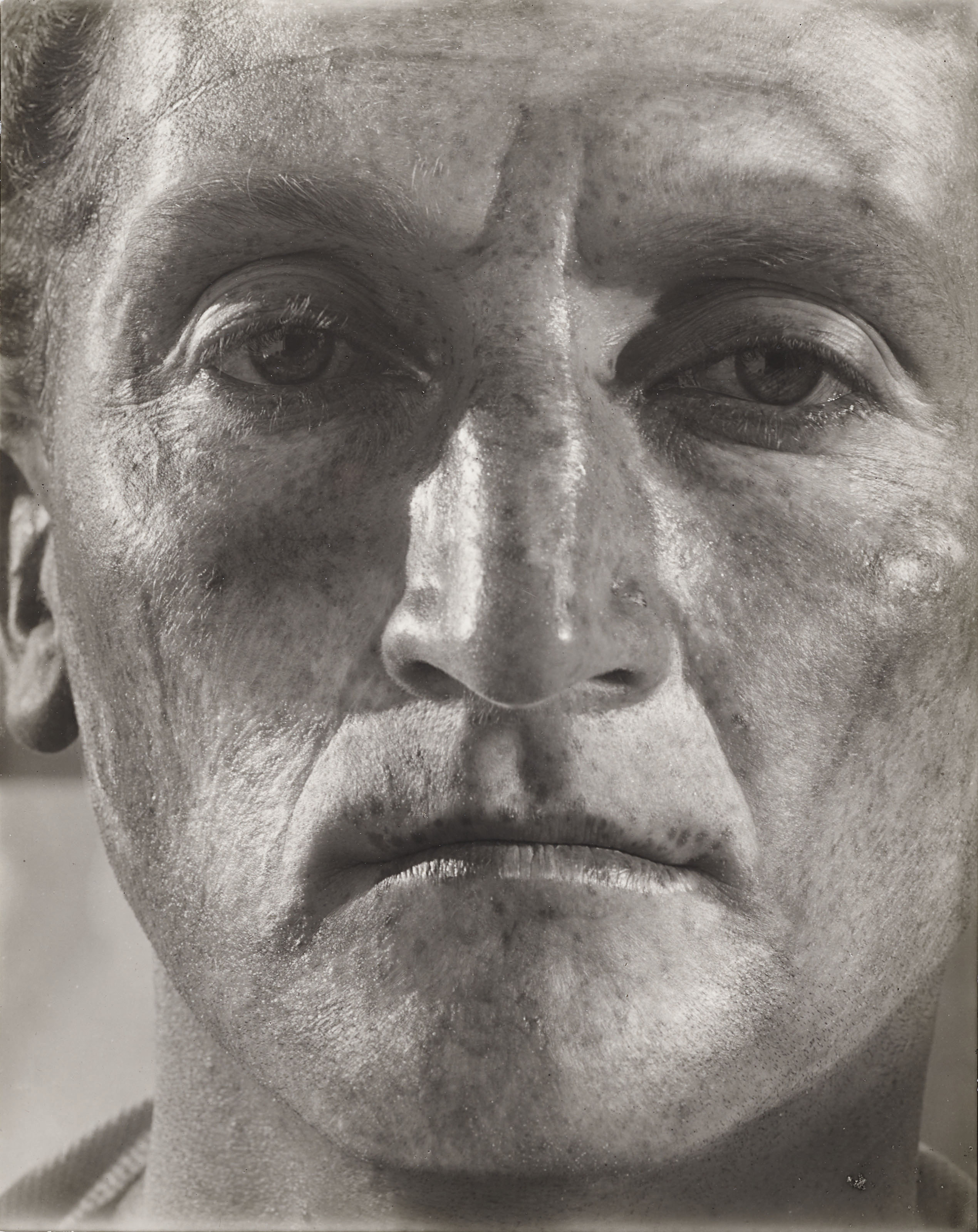

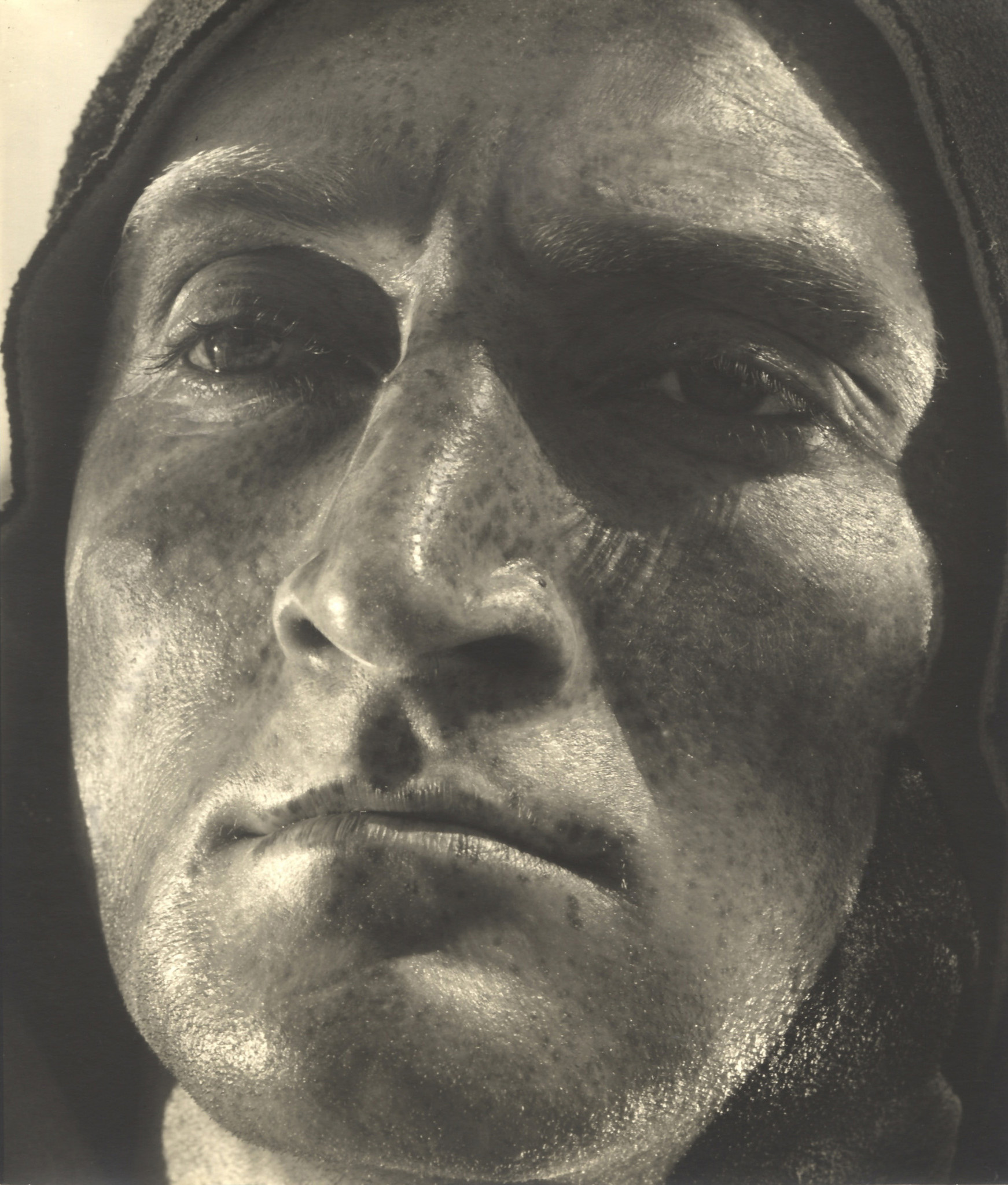

Helmar Lerski photographed the face of the construction engineer Leo Uschatz in a series of 140 closeups. Working in the blazing sun on a roof terrace in Tel Aviv, he achieved his dramaturgical lighting effects with up to sixteen mirrors and flags that helped him vary the intensity of the shadows. Having fled the National Socialists, the photographer and cameraman thus continued the studies in portrait photography he had begun in Berlin. He had already published his photo book Everyday Heads, containing closeup shots of anonymous persons, in 1931. Presented as impenetrable surfaces of mask-like rigidity, their faces speak of the conflict between emotionality and ideality. | Städel Museum

Über das Werk

Das Gesicht des Bautechnikers Leo Uschatz fotografierte Helmar Lerski in einer Serie von 140 Großaufnahmen. Die dramaturgische Lichtwirkung erzielte er mithilfe von bis zu 16 Spiegeln und Blenden, mit denen er in der prallen Sonne auf einer Dachterrasse in Tel Aviv unterschiedlich starke Schlagschatten erzeugen konnte. Damit setzte der vor den Nationalsozialisten geflüchtete Fotograf und Kameramann seine in Berlin begonnenen Studien zur Porträtfotografie fort. Bereits 1931 veröffentlichte er den Bildband Köpfe des Alltags, in dem er in nahsichtigen Aufnahmen unbekannte Menschen fotografierte. Ihre Gesichter werden maskenhaft-starr als undurchsichtige Oberfläche präsentiert und zeigen einen Konflikt zwischen Emotionalität und Idealität. | Städel Museum

At the beginning of 1936, Helmar Lerski started a new portraiture series. His model was a Jewish worker, who Lerski called ‘Uschatz’. In the next three months he produced 175 images of the man remembered as a jack of all trades in Lerski’s office.

Lerski had conceived his metamorphosis project as early as 1930. When asked about further plans, he responded to the film critic, Hans Feld, that he later wanted to “create a book of portraits of somebody. Fifty images of one and the same person”.

Working on the rooftop terrace of Lerski’s flat in Tel Aviv in the bright, morning sun, Lerski continually directed the light towards his model’s face, using a great number of mirrors. Designated by Lerski as his magnum opus, ‘Metamorphosis through Light’ was to “furnish proof, that a photographer can create freely, following his mind’s eye, like a painter, or sculpture.”

Lerski managed to reverse our traditional notion of portrait art without applying any of supernatural technical devices. It was all about the concept, the approach of an artist to the portrait execution. He neither followed the well-trodden way of attaining meticulous likeness of a portrait and a model nor he tried to render the individual features of a face. With the help of numerous mirrors and specific filters he managed to achieve such a forceful light-and- shade effects that the surface of a man’s face began o look like a sculptural landscape, abstract relief.

“Light is a proof, that a photographer can create freely, following his mind’s eye, like a painter, designer, or sculptor”.

The Palestine portraits became one of Lerski’s most important work series as a photographer. After several trips to Palestine since 1931 Lerski introduced to the world the portrait series of such an expressiveness and formal innovation that its appearance crossed the limits of simply an art event and called the ideological, nationalistic and religious discussions. While creating his famous Judaic portraits, the artist was obsessed by the idea of the official documentation of Jewish nation characters in all its importance and grandeur.

“I want to show only the prototype in all its off-shoots, and, what is more, I want to show him so intensely that the prototype is recognizable in all later branches”.

Later this series was enhanced by the Arab characters and hands portraits exhibited thereafter in the Tel-Aviv Museum (1945).

An intellectual, a person of multimedia consciousness having been for not less than half a century ahead of his time. Nowadays Helmar Lerski together with Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen, is acknowledged in the professional environment as one of the classics and main innovators of the 20 century photography.

Exhibitions: Helmar Lerski. Gary Tatintsian Gallery, Moscow, Russia. February – March 2008