images that haunt us

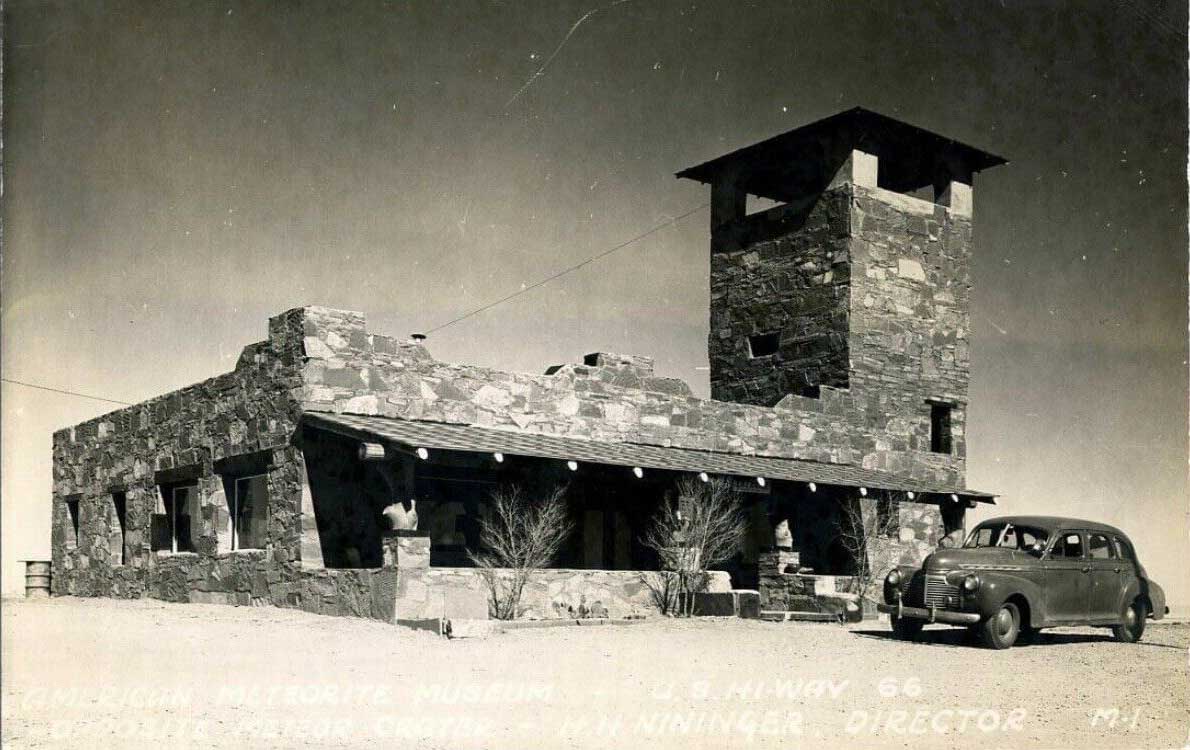

The Barringer Crater, also known as Meteor Crater, is a large impact crater located in Arizona, in the United States (*). It is about 1.2 kilometers (0.75 miles) in diameter and about 170 meters (570 feet) deep. The crater was formed about 50,000 years ago when an iron meteorite struck the Earth’s surface. It is unusually well preserved in the arid climate of the Colorado Plateau, in fact the (alleged) best preserved meteorite impact site on Earth and is a popular tourist destination. The crater is named after the mining engineer and businessman Daniel M. Barringer, who was the first person to suggest that it was formed by the impact of a large iron-metallic meteorite on Earth.

(*) The site had several earlier names, and the fragments of the meteorite are officially called the Canyon Diablo Meteorite, after the adjacent Cañon Diablo.

This is a Public Domain Work. Please credit both “University of Southern California. Libraries” and “California Historical Society” as the source. Digitally reproduced by the USC Digital Library.

Meteor Crater (also known as Barringer Crater) on Earth is only 50,000 years old. Even so, it’s unusually well preserved in the arid climate of the Colorado Plateau. Meteor Crater formed from the impact of an iron-nickel asteroid about 46 meters (150 feet) across. Most of the asteroid melted or vaporized on impact. The collision initially formed a crater over 1,200 meters (4,000) feet across and 210 meters (700 feet) deep. Subsequent erosion has partially filled the crater, which is now only 150 meters (550 feet) deep. Layers of exposed limestone and sandstone are visible just beneath the crater rim, as are large stone blocks excavated by the impact.

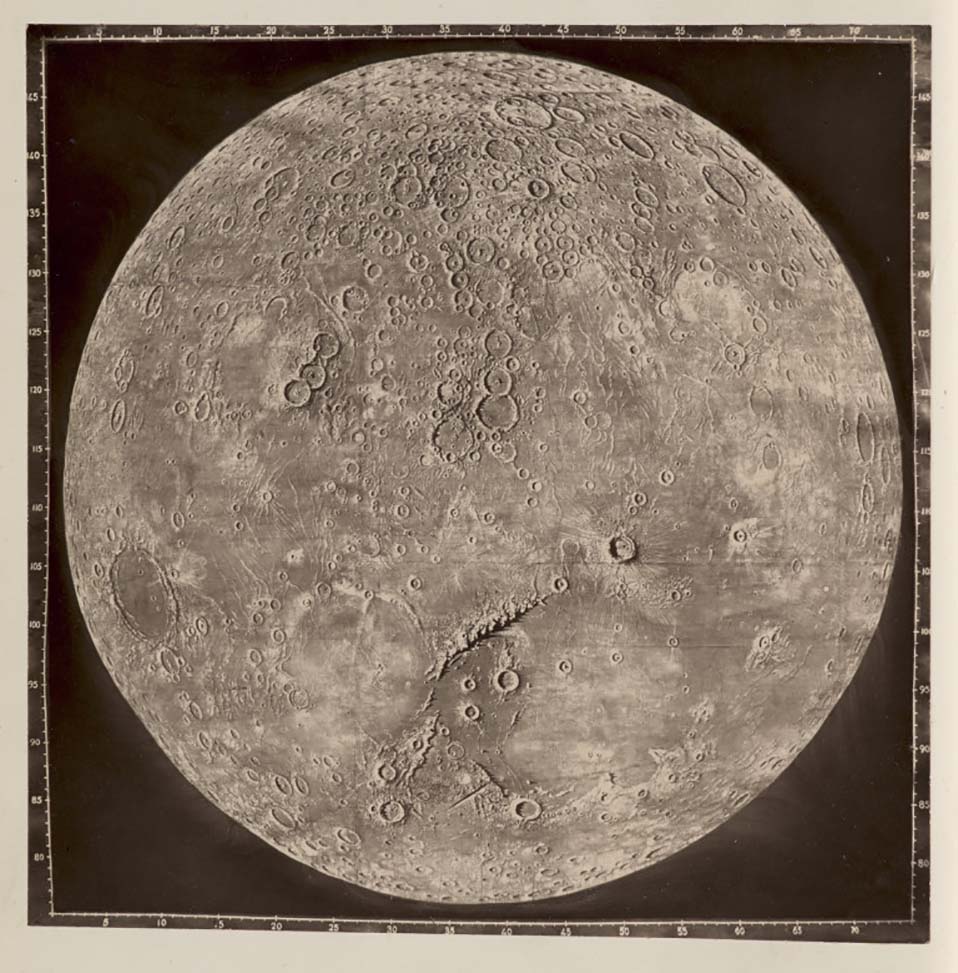

Impacts have shaped the Earth and Moon since early in the history of the solar system. In fact, the Moon likely formed when a proto-planet (likely the size of Mars) crashed into the Earth over 4.5 billion years ago. The collision sprayed material from the two worlds into orbit around the Earth. The debris coalesced and formed the Moon.

Meteorites continue to strike both the Earth and Moon. Micrometeorites bombard the Earth continuously. Larger asteroids hit Earth less frequently. Asteroids measuring roughly 50 meters (160 feet) across strike the Earth every 1,000–2,000 years, while more than 100,000 years typically elapse between strikes from asteroids larger than 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) across. [quoted from NASA]

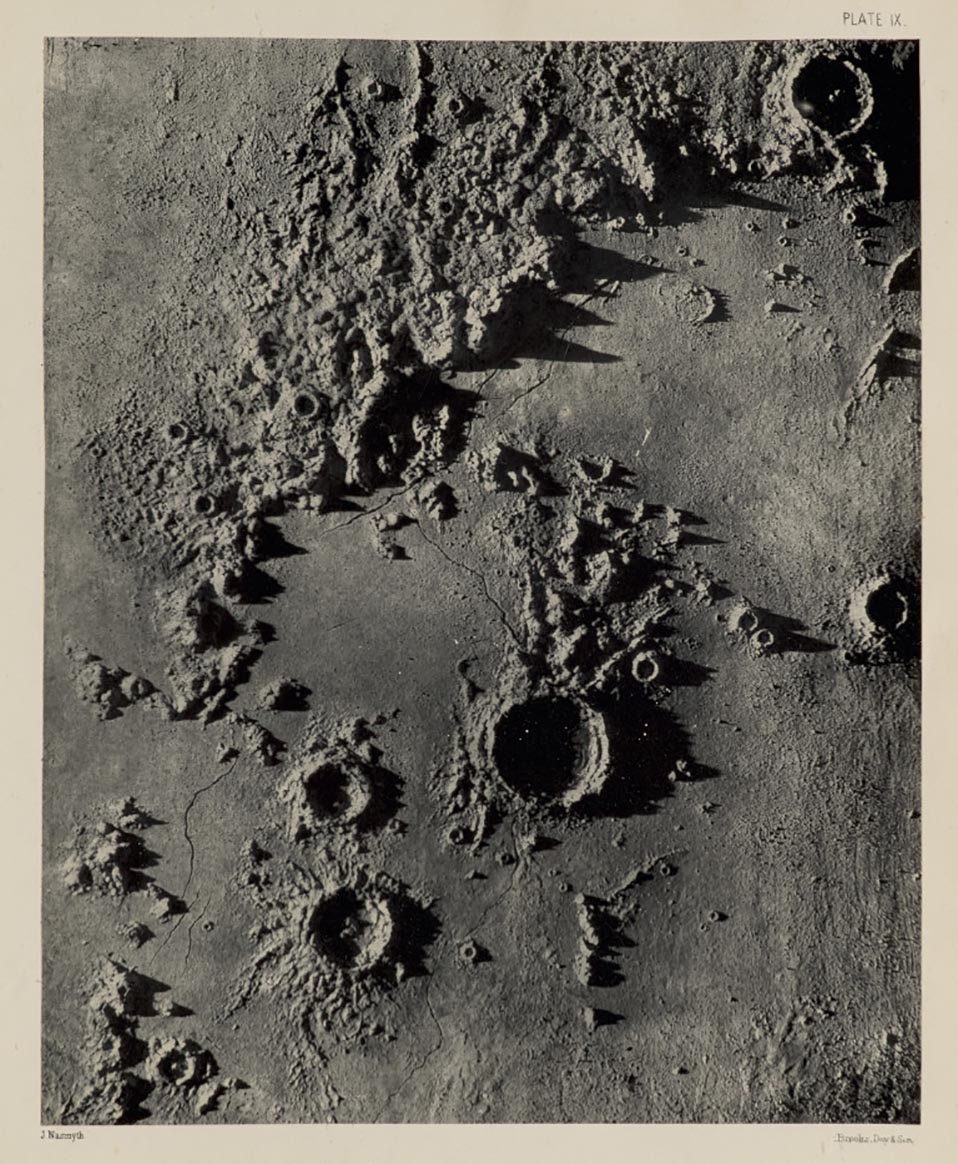

The Moon; Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite (1873). With 46 text illustrations, and 25 plates on 24 leaves, comprising 12 mounted Woodburytypes of lunar models, 6 photogravures, 4 autotypes, 2 lithographs, and one chromolithograph. First edition of the classic and influential text on lunar geology by James Nasmyth (1808-1890) and James Carpenter. It was thanks to Nasmyth’s superior talent for visual communication that this book held the misconception that the lunar craters were volcanic for almost 100 years. It was not until 1969, when the Apollo 11 space mission brought back geological samples from the moon, that the impact theory gained credibility and the volcanic hypothesis was finally abandoned. – The book was one of the first to be illustrated with photomechanical prints, praised by a contemporary reviewer as one of the “truest and most striking representations of natural objects”, although the illustrations are not actual photographs of the Moon. The book is the result of decades of studies Nasmyth, a retired industrial engineer and amateur astronomer, made of the moon with a large telescope of his own design. He made numerous studies and maps of the moon, recording its topographical features with extraordinary clarity and precision. Nasmyth and Carpenter pointed the camera not at the lunar surface itself, but at a series of hand-made plaster models based on these drawings. It was already possible to photograph the Moon, but the highly magnified views they sought could only be achieved using plaster models photographed outdoors in glaring light, both to replicate the oblique angle of the sun’s rays on the lunar surface and to reveal the subtle topographical variations of the model’s surface. – Nasmyth’s first drawings of the moon were made as early as 1842 and were first exhibited in Edinburgh in 1850. The first public presentation of photographs of Nasmyth’s models took place at the Manchester Photographic Society exhibition in 1856. – This edition contains seven different prints by six printers, including two different variants of the Woodburytype. [quoted from Jeschke van Vliet]

There are many different ways of creating and viewing stereoscopic 3D images but they all rely on independently presenting different images to the left and right eye.

Anaglyphs are a straightforward way of presenting stereo pair images is the stereoscopic 3D effect achieved by means of encoding each eye’s image using filters of different (usually chromatically opposite) colors, typically red and cyan. Anaglyph 3D images contain two differently filtered colored images, one for each eye. When viewed through the “color-coded” “anaglyph glasses”, each of the two images reaches the eye it’s intended for, revealing an integrated stereoscopic image. The visual cortex of the brain fuses this into the perception of a three-dimensional scene or composition.

There are three types of anaglyph glasses in common use: red-blue, red-cyan, and red-green.

![Wenceslaus Hollar :: Vlinders, torren en een mot [Butterflies, Beetles and a Moth], Antwerp, 1646. Insecten (series title)

Muscarum Scarabeorum (series title). Etching. | src Rijksmuseum](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52423282575_bc2018693b_4k.jpg)

![Wenceslaus Hollar :: Dragonfly [Libellen], Antwerp, 1646. | src Rijksmuseum / Detail](https://unregardobliquehome.files.wordpress.com/2022/10/wenceslaus-hollar-insects-rijksmuseum-b1-crp.jpg)

![Wenceslaus Hollar :: Dragonfly [Libellen], Antwerp, 1646. | src Rijksmuseum](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52422828411_0ce4850237_3k.jpg)

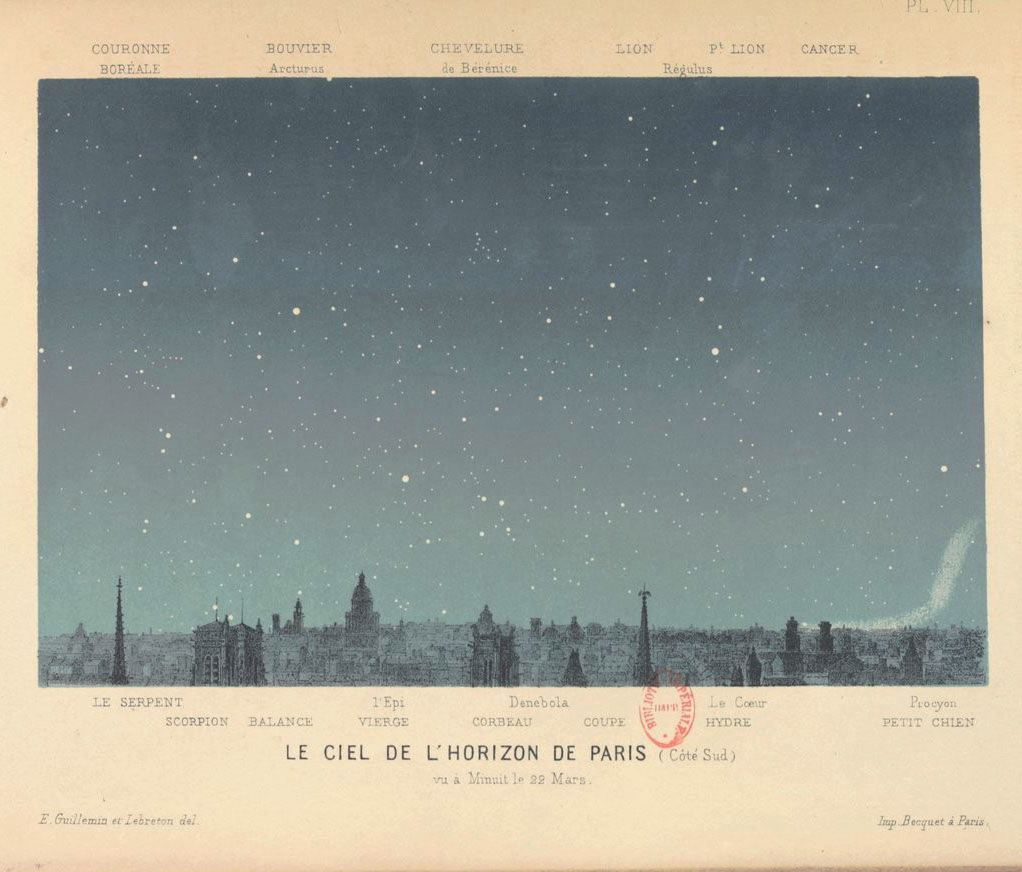

![Le ciel de l'horizon de Paris (Côté Sud ) vu à Minuit le 29 Mars [detail] | BnF · Gallica](https://unregardobliquehome.files.wordpress.com/2022/08/le_ciel_-_notions_dastronomie_...guillemin_amedee_bpt6k62098808_437-1.jpeg)

![Le ciel de l'horizon de Paris (Côté Sud ) vu à Minuit le 20 Décembre [detail] | BnF · Gallica](https://unregardobliquehome.files.wordpress.com/2022/08/le_ciel_-_notions_dastronomie_...guillemin_amedee_bpt6k62098808_411-1.jpg)