images that haunt us

![Aenne Biermann :: Orchid, ca. 1930. Gelatin silver print. [Detail] From : Aenne Biermann : Up Close and Personal at Tel Aviv Museum of Art](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/aenne-biermann_orchid-ca.-1930-detail-tel-aviv-museum.jpg)

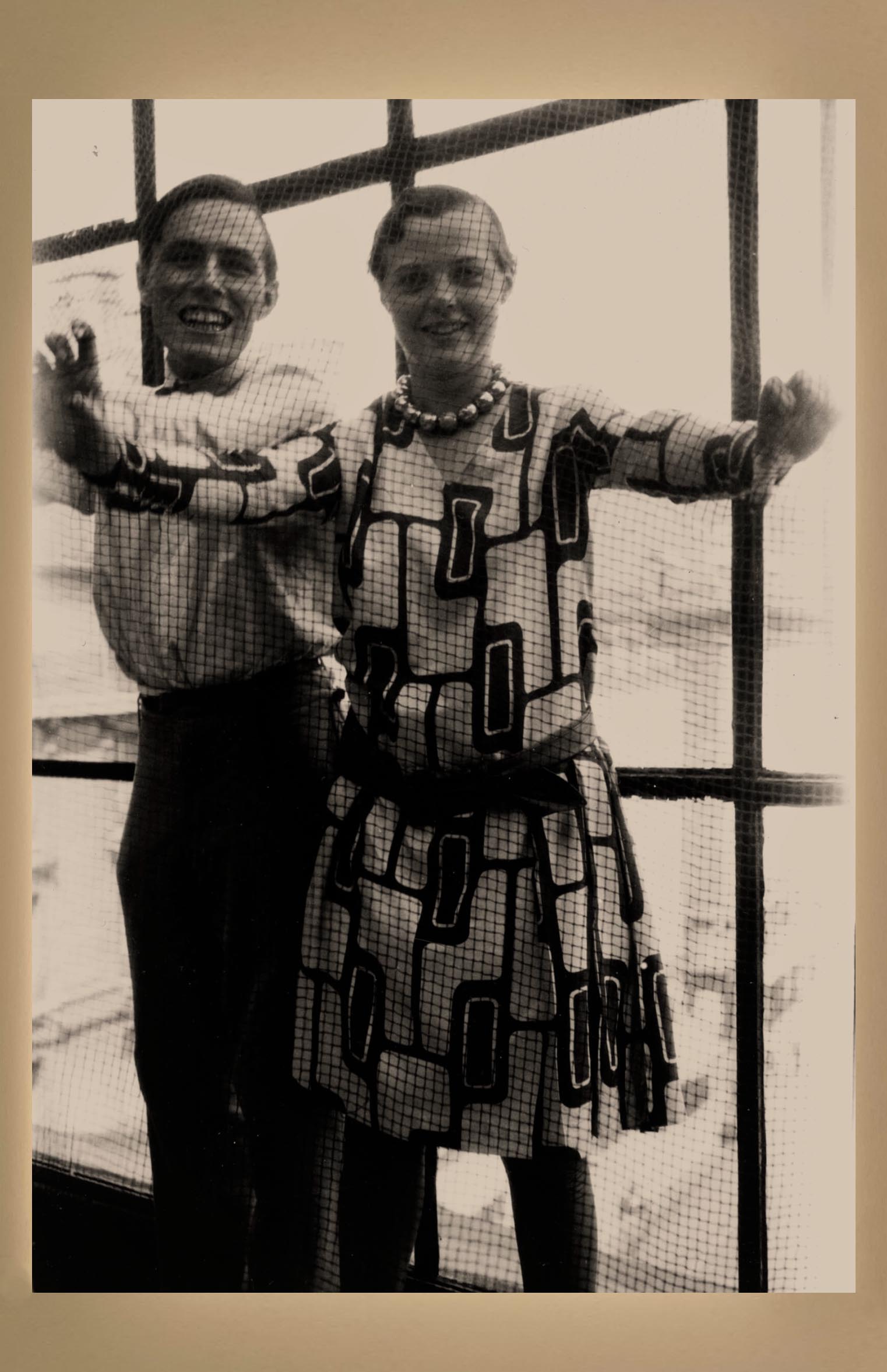

Charlotte Perriand’s ball-bearings necklace was exhibited in 2009 at the exhibition “Bijoux Art Deco et Avant Garde” at the Musee Des Arts Decoratifs in Paris and, in 2011, in the show “Charlotte Perriand 1903-99: From Photography to Interior Design” at the Petit Palais. The necklace became, for a short period, synonymous with Perriand and with her championing of the machine aesthetic in the late 1920s and has subsequently attained the status of a mythical object and symbol of the machine age. This essay considers the necklace as an object and symbol in the context of modernist aesthetics. It also discusses its role in the formation of Perriand’s identity in the late 1920s, when she was working with Le Corbusier, and aspects of gender and politics in the context of the wider modern movement. [more on Semantic Scholar]

“I had a street urchin’s haircut and wore a necklace I made out of cheap chromed copper balls. I called it my ball-bearings necklace, a symbol of my adherence to the twentieth-century machine age. I was proud that my jewelry didn’t rival that of the Queen of England.”

Perriand had asked an artisan with a workshop in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine to make the piece out of lightweight chrome steel balls strung together on a cord. The piece was inspired by Fernand Léger’s still life “Le Mouvement à billes” (1926).

The necklace became a symbol of Perriand’s passion for the mechanical age […] (see also: Charlotte Perriand’s “Ball Bearings” Necklace on Irenebrination)

“Art is in everything,” insisted Charlotte Perriand. […] When you see Charlotte’s chaise longue, chair, and tables in front of that immense Léger, you cannot imagine the design without the art—it is a global vision.

On an adjacent wall, Collier roulement à billes chromées (1927)—a silver choker made from automotive ball bearings that Perriand not only designed but wore—is placed next to a Léger painting, Nature morte (Le mouvement à billes) (Still life [Movement of ball bearings], 1926). [quoted from William Middleton review of the exhibition Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World, on Gagosian]

She recalls how in 1927 at the age of just 24 she marched into the studio of Le Corbusier in Paris and showed the master architect her designs in order to present herself as an architect. He looked at everything and then said, “Mademoiselle, we don’t embroider cushions here.” [src indion]

The young woman bathed confidently in the sparkling energy of the “années vingt”, learned the Charleston, admired Josephine Baker, wore her hair cropped short and had a necklace made of chrome-plated balls, which she called her “ball bearings” – a provocation of industrial aesthetics. Modernism was gathering momentum. In her apartment, a car headlamp hung above her extending table made of materials used in automotive production. The direction was clear: we need to get away from the classical parlour. [src indion]

Charlotte Perriand did not have to wait until her meeting with Le Corbusier to give vent to her creativity; it was long before then that she started to design pieces completely off her own bat. To be sure, the turning point came for her in 1927, when she read the Swiss architect’s two essays, Vers une architecture and L’art décoratif aujourd’hui, and had a revelation: “Those books made me see past the wall that was blocking my view of the future. So I took a decision: I was going to work with Le Corbusier.” But their first meeting was a disaster. She presented herself at no. 35 Rue de Sèvres, the studio that the Swiss architect and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret had set up in a long corridor that had formerly been the cloister of a Jesuit monastery (a building that was later demolished and replaced by a glass and concrete construction). She took out her drawings and when Le Corbusier asked her what she wanted, blurted out the only sentence she had prepared: “To work with you.” He looked her up and down through his round spectacles, glanced through the drawings and dismissed her with the words: “We don’t embroider cushions here.” Disheartened, Perriand turned on her heel, but not before telling Le Corbusier about her Bar sous le toit on show at the Salon. [quoted from Klat magazine]

These were not easy times for women: the world of architecture was peopled with extremely misogynous men. Charlotte felt herself to be a failure: she had not been able to get herself accepted. So it was a delightful surprise for her to find out, a few days later, that Le Corbusier had seen her furniture and was ready to let her join his studio to design the interiors of his new buildings. The mutual understanding between them in design would be so great that Charlotte Perriand’s name would be overshadowed and even erased by Le Corbusier’s, even though their collaboration would last for about ten years. [quoted from Klat magazine]

Those were years of great complicity. The pair shared a passion for emptiness: “Vacuum is all potent because all containing,” as Taoism teaches us. But they would also be years filled with enthusiasms and jealousies, seeing that, after her divorce from Percy Kilner Scholefield, Charlotte discovered Moscow and Berlin, founded an association of artists and had a love affair with Le Corbusier’s cousin and partner Jeanneret, forming a fruitful and complicated relationship with him. Together they would embark on research into art brut, studying with Fernand Léger the shapes of pebbles on the beaches of Dieppe, the fractals of fossils and the trunks of trees. And together they would work until 1940. [quoted from Klat magazine]

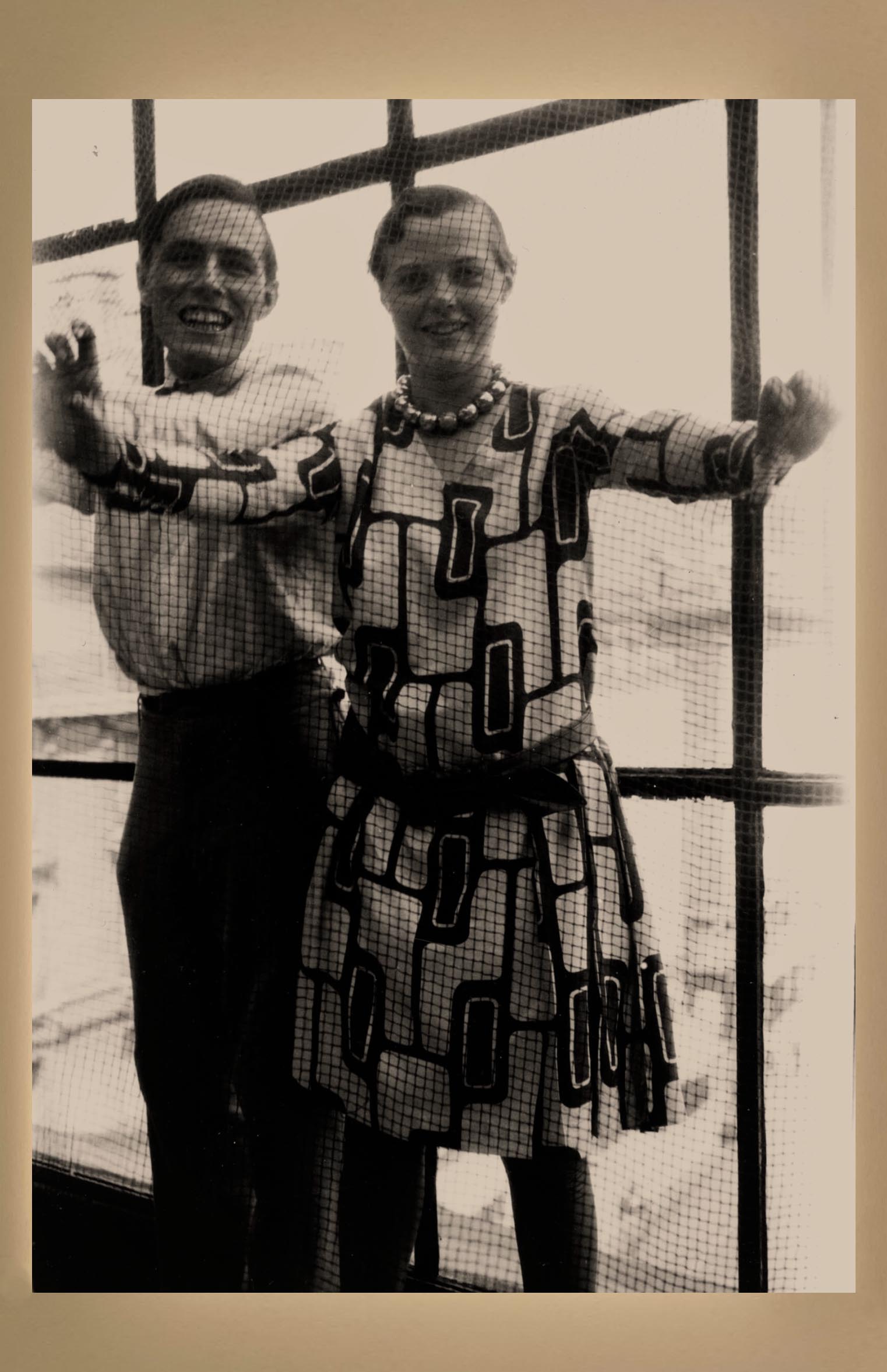

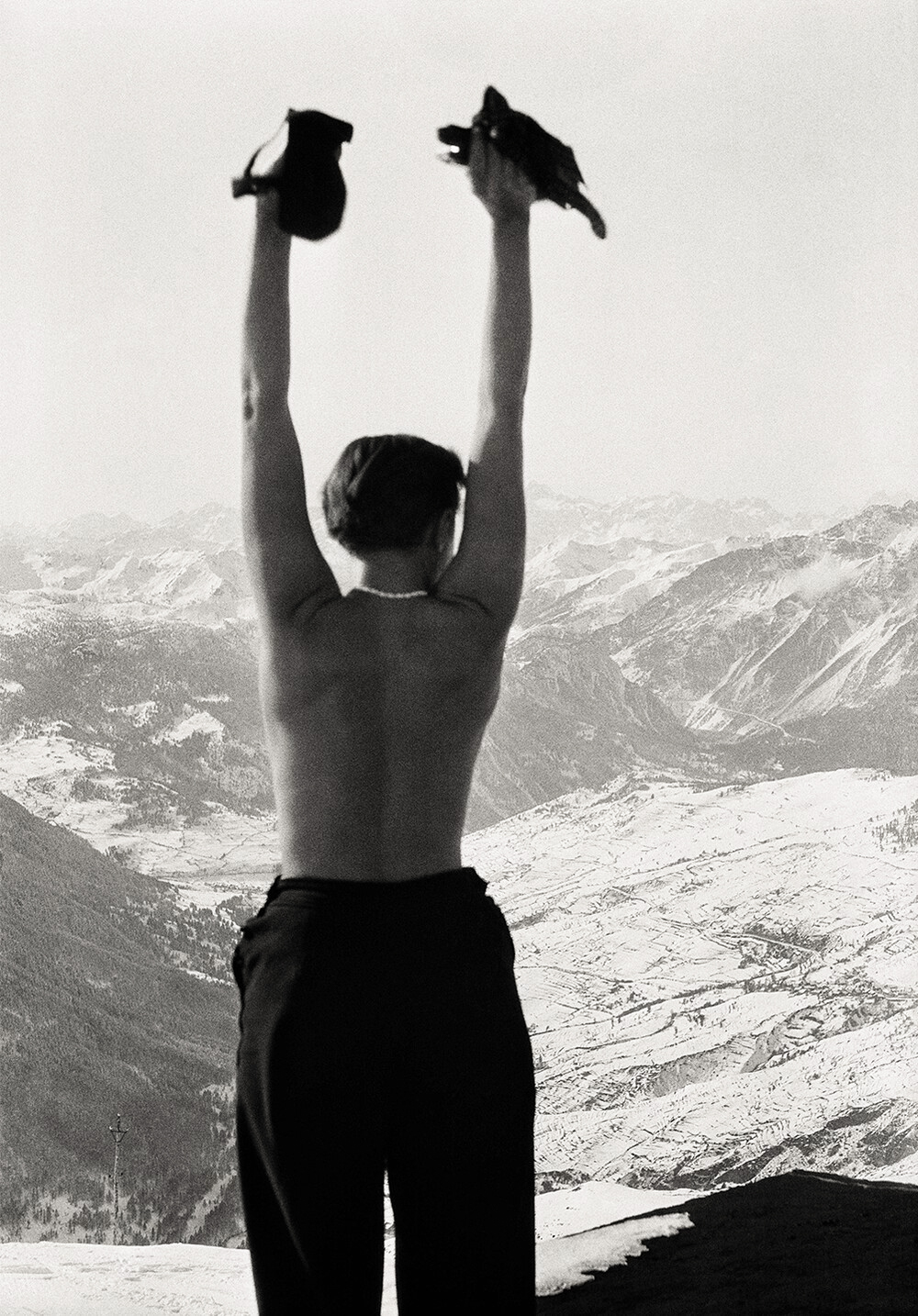

In the summer of 1940 Charlotte Perriand left for Tokyo. Appointed, thanks to her friend, colleague and former intern Junzo Sakakura, an adviser on industrial design to the Japanese government; Perriand was supposed to stay in Japan for just a year and a half to prepare a major exhibition. She was to remain there for six years, as the war upset her plans, separating her from Jeanneret and leading her to finding a new love, Jacques Martin, who would become her second husband and the father of her daughter Pernette. From that time on, the life of this infinitely resourceful girl from the mountains, a skilled skier and off-piste enthusiast, but also a lover of the sea and fanatic swimmer, would be an unending series of encounters and discoveries in a continual process of renewal in order to try out new forms and unprecedented solutions. [quoted from Klat magazine]

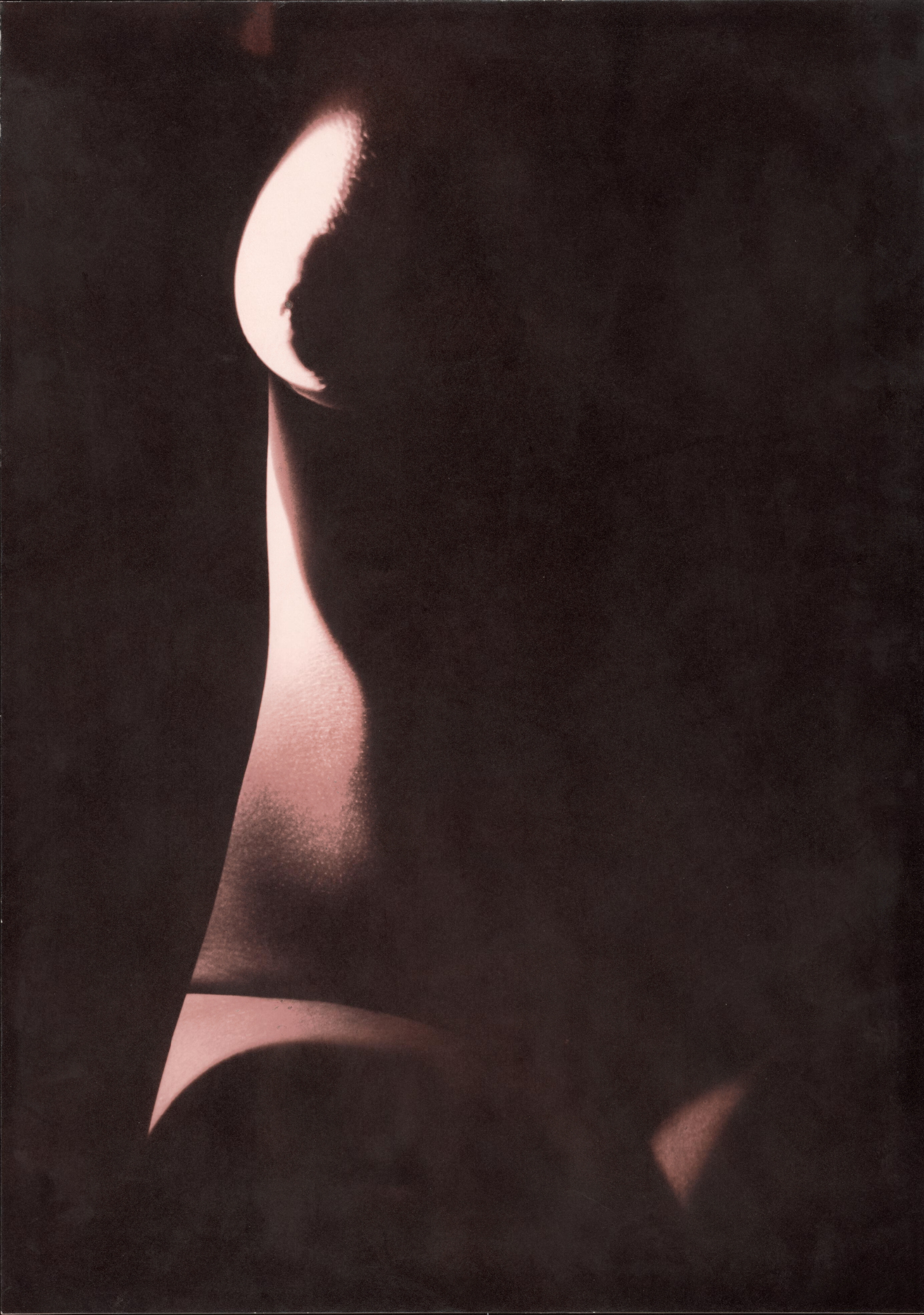

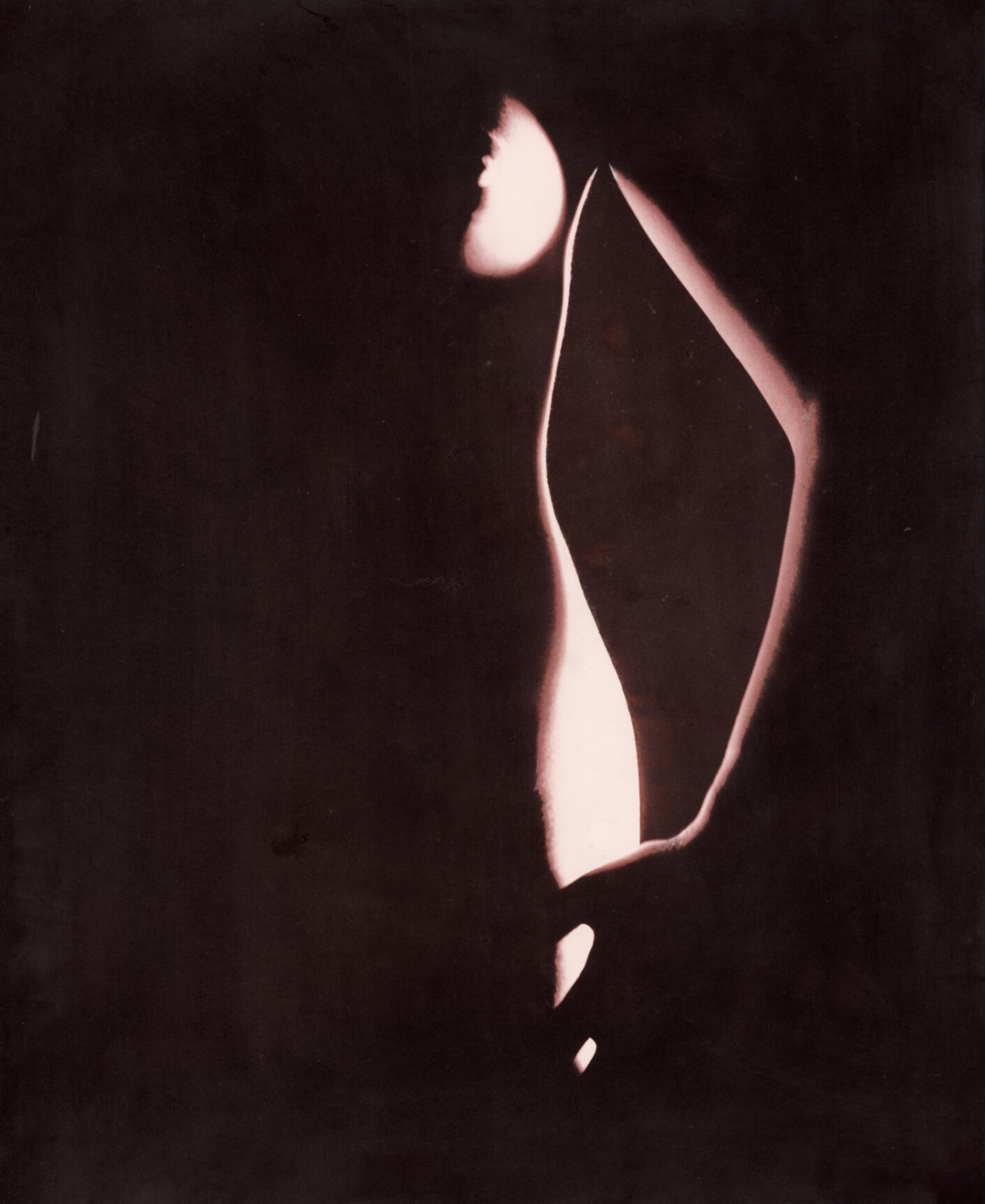

Oľga Bleyová (1930 – 2019) belongs to the generation of Slovak photographers that emerged on the art scene betweenthe 1960s and 1970s, and was open to experimenting in photography. She brought to photography her sense of imagination and poeticism, and conveyed her female view into a thoroughly articulated message. Her nudes can, without any doubt, be considered among her most distinctive work.

![Clara E. Sipprell :: [Clara Sipprell or Irinia Khrabroff at the Grand Canyon Rim], 1929. Gelatin silver print. | src Amon Carter Museum](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52593043396_4315025c51_o.jpg)

![Unknown; [Clara Sipprell and Irina Khrabroff positioning camera], ca. 1929. Gelatin silver print. | src Amon Carter Museum of American Art](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/clara-e.-sipprell-1885-1975-clara-sipprell-and-a-irina-khrabroff-positioning-camera-ca-1929-amon-carter-museum.jpg)

![Clara E. Sipprell (1885-1975) :: [Clara Sipprell or Irina Khrabroff by Great Rock, Grand Canyon], 1929. | src Amon Carter Museum](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52593468455_df8a035baa_o.jpg)

![Unknown; [Clara Sipprell and Irina Khrabroff having a picnic], ca. 1920s - 1930s. Gelatin silver print. | src Amon Carter Museum of American Art](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52608611847_a1b46a8a03_o.jpg)

All images: Archival Pigment Prints on Hahnemuhle Fine Art Paper

“Flowers in Dutch Light”

Taking inspiration from the mastery of Dutch Golden Age painters and by blending this with 20th century photographers and their use of light, Stella Gommans’ resulting work is poetic, aesthetic, elegant and minimalistic. For Gommans – a former dancer and a largely self-taught photographer, nature in its broadest sense is an unfailing source of inspiration.

This exquisite body of work celebrates flowers – capturing their different phases and the variety of shapes and colours – each telling their own story. In beautiful detail she depicts how the light emphasises the elegance of the stem, or how it catches the leaf, or how it allows us to catch a glimpse of the brittle petals and the burst of colours when in full bloom. Gommans invites the viewer to look closer and sometimes even take a step back, because in that instant – hidden aspects emerge – like a choreography, a fabulous dance.

‘A Declaration of Love, flowers in Dutch light’ is a series that symbolises life.

Flowers naturally bloom in all their strength, vulnerability and beauty – with elegance and grace – poetically captured in that single moment in time, never to be repeated again. Quoted from Elliott Gallery

All images: Archival Pigment Prints on Hahnemuhle Fine Art Paper