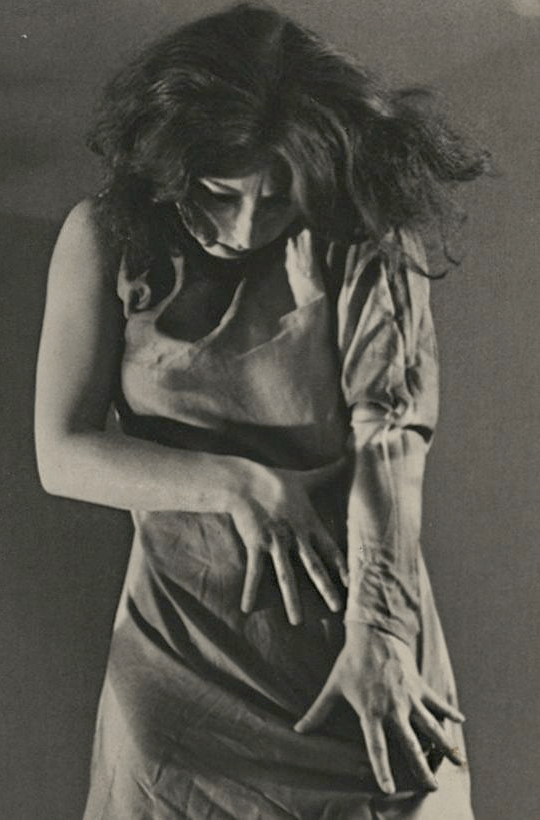

Ruth St. Denis, circa 1920s

images that haunt us

The tragic life of Sasha

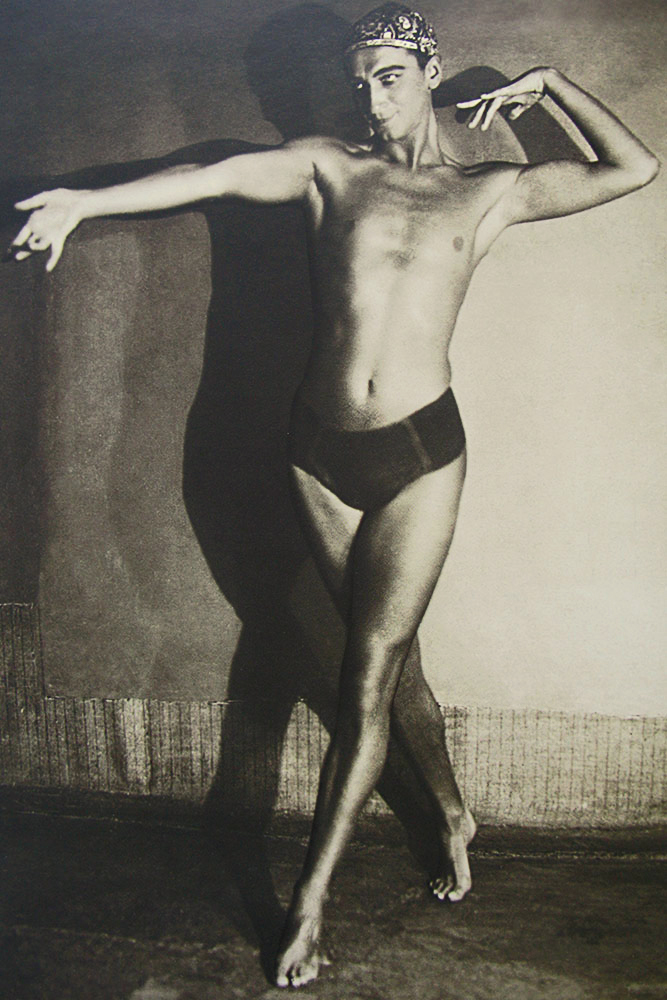

Soviet dance pioneer Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Ziakin (1899-1965), known as Rumnev or Alexander Rumnev, took his pseudonym from the family estate: Rumnia.

Rumnev started dancing after Duncan’s show in 1905. Little Sasha Zyakin (Rumnev) had not seen Duncan’s performance in Moscow in 1905 (he only heard his parents talk about it), the boy «stripped himself of all his clothes, wrapped into a sheet and attempted to reproduce her dance in front of the mirror».

From an early age, Aleksandr Rumnev (1899-1965) dreamt of dancing, yet he could do it only after graduating from high school. In 1918 he took up ballet classes, and a friend brought him to Liudmila Alekseeva’s studio. For the talented student, Alekseeva choreographed several dances to the music by Rakhmaninov and a dance of the ocean wave to the etude by Carl Czerny. Tall, slim and flexible, Rumnev was a born dancer, and within a year he had already founded his own company. He also performed with other companies including Lev Lukin’s Free Ballet (see below). The art critic Aleksey Sidorov found him «stunning»; he believed that «even the West» could be proud of such dancer.

During the Civil War private dance studios experienced hard times for the shortage of rooms with heating. As a matter of survival, Rumnev suggested to create an umbrella-studio, A Search in Dance. The space was provided by Alekseeva, there Rumnev taught dance and pantomime, and other dancers gave classes of gymnastics, modern dance, rhythmical gymnastics, «expression» and «musicality». Yet in winter it was so cold that, sprayed with water to prevent sliding, wooden floor was quickly covered with ice.

In 1920 Rumnev joined the Chamber Theatre (Kamernyi Teatr) as a pantomime actor and teacher. He also choreographed his own «grotesque» dances commenting that «this was a tragic grotesque». One of his solos, The Last Romantic, to music by Scriabin, was about a «contemporary Don Quixote». Yet, for the new proletarian culture, Rumnev was «too refined, he moved too elegantly, waving with aristocratic narrow hands, striking with broken movement of long arms and legs». Critics found him old-fashioned and ‘decadent’. He was also gay which became criminalized under Stalin. In 1933 Rumnev fled Moscow. Several years later he was arrested in the provinces and served a prison sentence. In 1962 he finally succeeded in founding the Experimental Theatre for Pantomime, the genre he had been committed to from the beginning. Sadly, Rumnev died two years later, and his theatre did not survive his death.

quoted from Irina Sirotkina: The Revolutionary Body, or Was There Modern Dance in Russia?

As a young girl, Alekseeva (1890-1964) loved dancing. Seeing her dance, the sculptress Anna Golubkina, her neighbor in the small town of Zaraisk, sent her to Moscow to study with Rabenek. In 1911 Liudmila joined her classes and quickly became one of the company’s prime dancers. Two years later she left the company dissatisfied with both the life on the road and Rabenek’s way of teaching which appeared to her not too serious. Alekseeva realized that, in order to become professional and to compete with ballet, modern dance had to develop its own training, as efficient as the classical bar.

An ambitious dancer, she wanted to combine Anna Pavlova’s virtuosity with the performance of tragic actress. In 1914, Alekseeva opened her own studio. «She was very young, tall, slim, and ironic, with tomboy manners and a deep hypnotic voice. Her dance had nothing of ballet. It was not even dance in the usual sense of the word. Rather, she taught the art of moving graciously. Every exercise was like a short étude of danse plastique»

Her firsts choreographies were solos: the Bacchanalia to music by Saint-Saëns and The Butterfly to Grieg (in continuation of both Isadora Duncan and Anna Pavlova’s dances). Her choreography including The Dying Birds to Chopin’s Revolutionary Etude, for a group of dancers, was preserved by her students.

In 1918 Alekseeva quickly realized that the wind had changed. She registered her studio with the People’s Commissariat of Enlightenment. For the first anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, she choreographed a trilogy, Darkness. A Break Through. La Marceillaise, to the music by Schumann, Liszt and her husband, the composer Meerson. Allegedly, the leader of the Soviet state Vladimir Lenin attended one of the performances. Like Isadora, Alekseeva’s ambition was bringing dance to ‘the masses’ and transforming every woman’s life with the help of ‘harmonious’, or ‘artistic’ gymnastics. Later she became one of the founders of the female sport with the same name, khudozhestvennaia gimnastika.

quoted from Irina Sirotkina: The Revolutionary Body, or Was There Modern Dance in Russia?