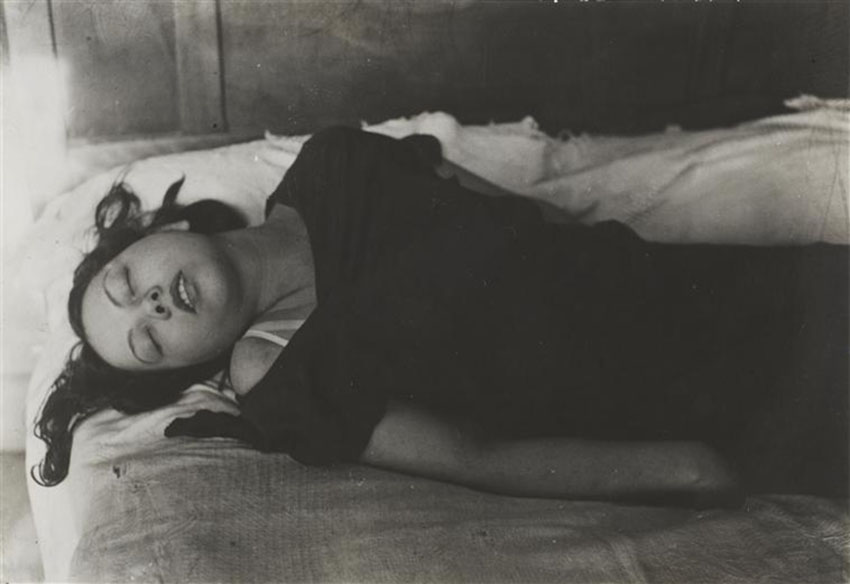

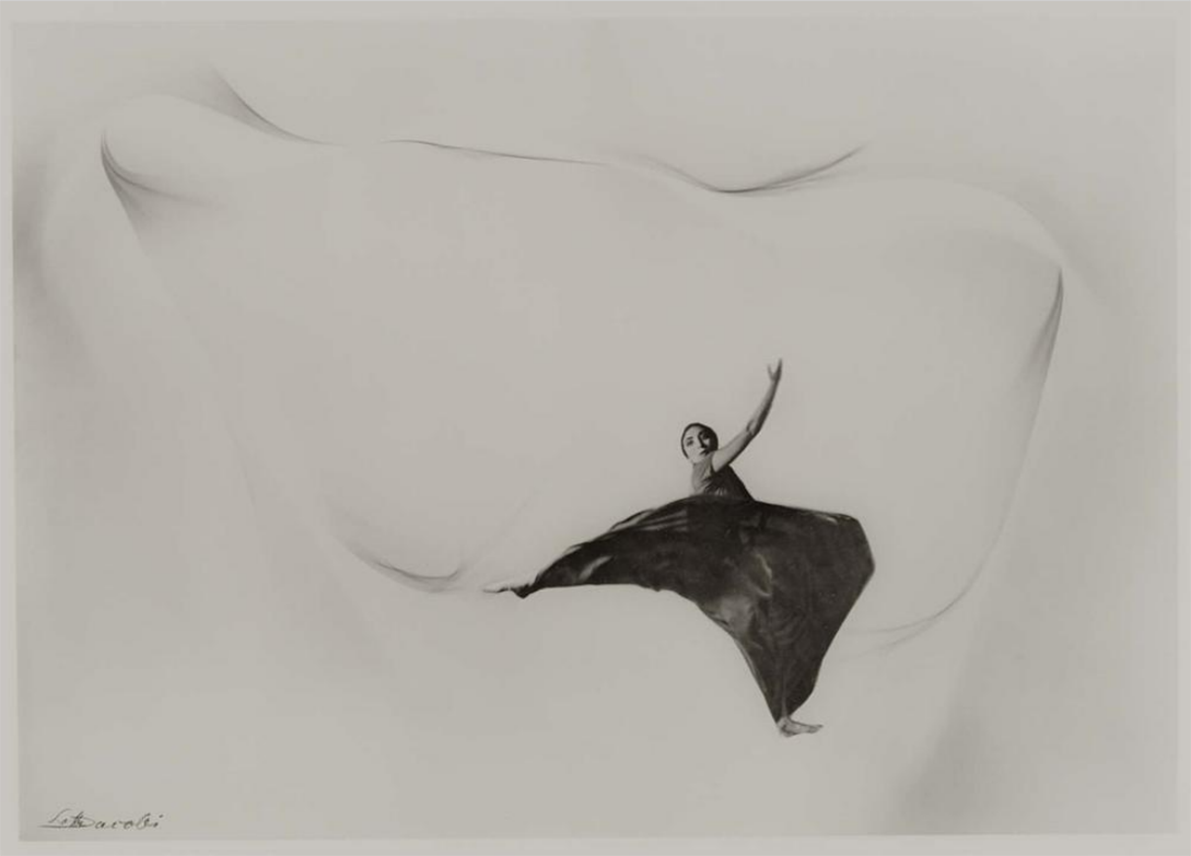

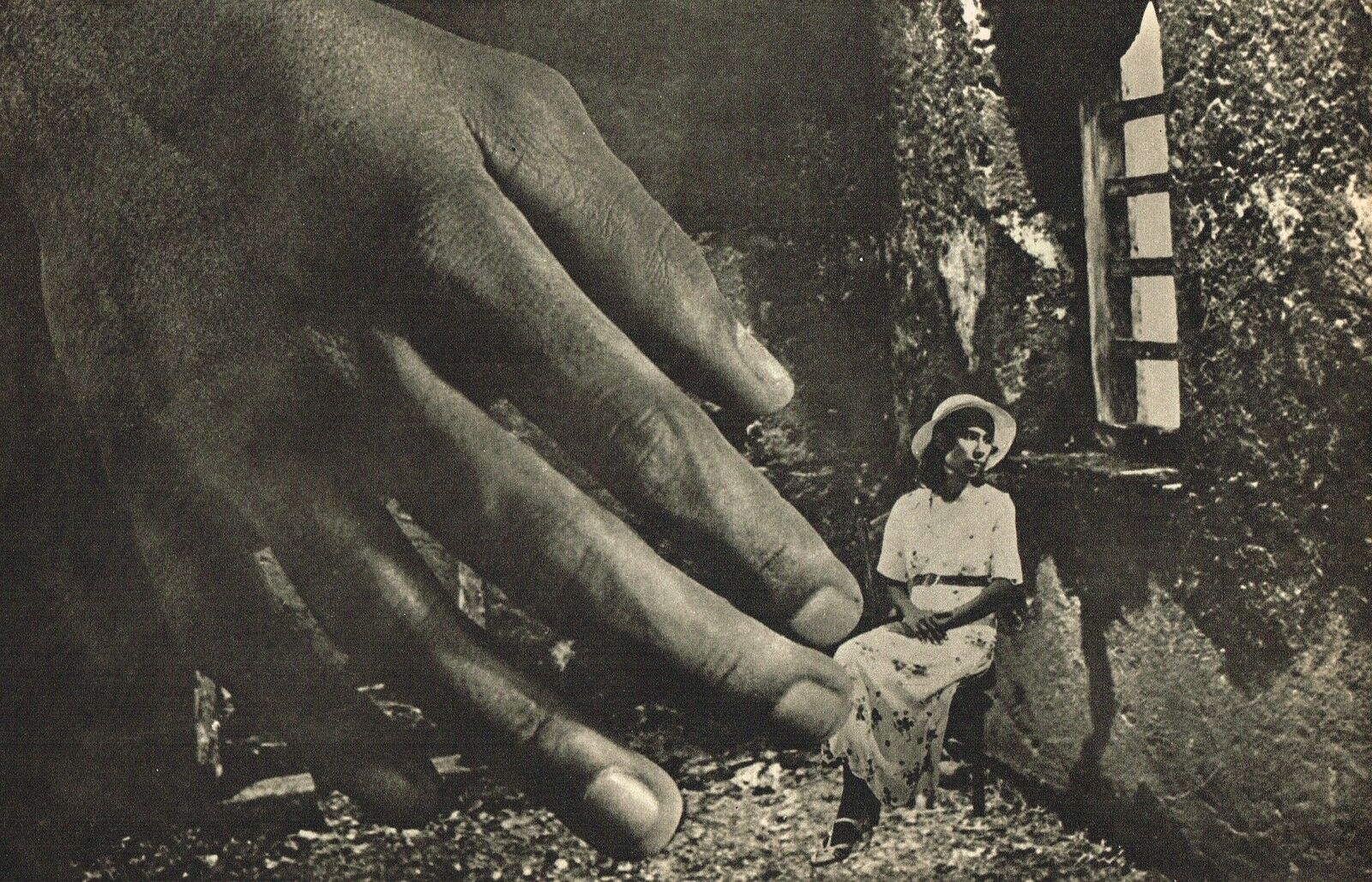

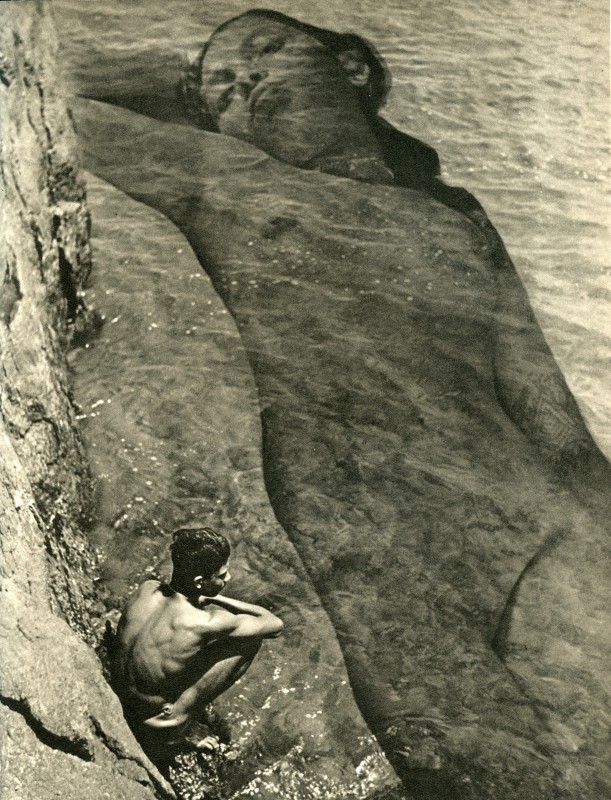

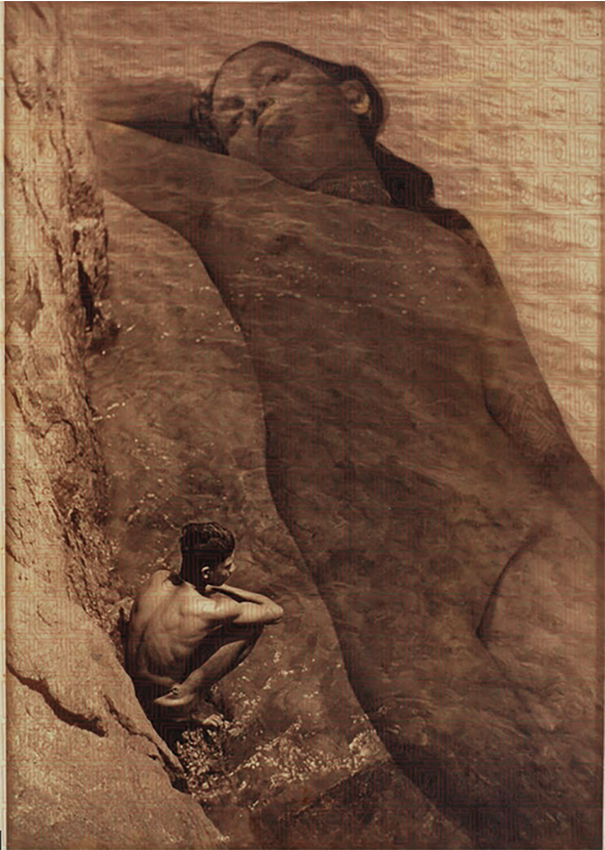

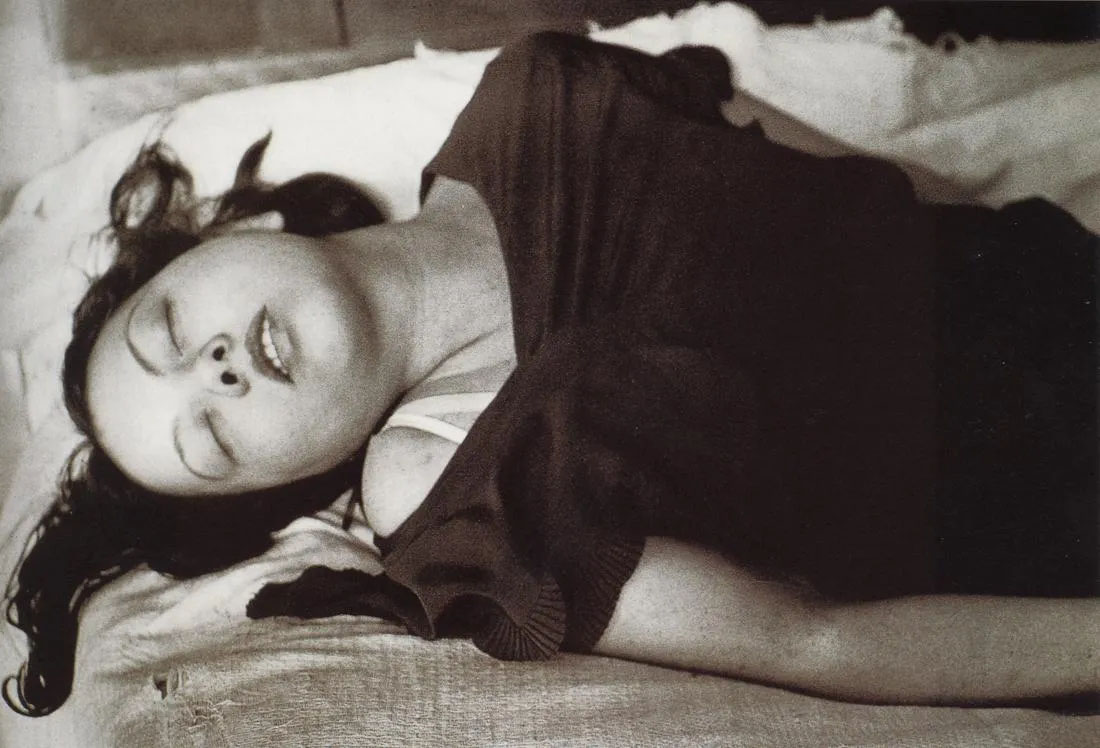

The Phenomenon of Ecstasy, is a photomontage built in a spiral: it is made up of 32 photos organized in a labyrinth of photos which wind up, drawing the eye in a hypnotic way towards the central photo, a portrait of a woman by Brassaï. This photo was part of a series of «femmes en jouissance onirique» (women in dreamlike enjoyment), taken in 1932.

Dalí saw in the convolutions of Art Nouveau a form of madness or intoxication. Brassaï’s portrait of the “overthrown” woman fit perfectly with his point. It therefore logically lands at the heart of a system which functions like a puzzle.

The historian Michel Poivert in his analysis of «Le phénomène de l’extase» ou le portrait du surréalisme même (1997) first lists the elements that make up the image: “most of them show a woman’s face that the title invites us to consider in ecstasy. In addition to these female faces, there are three male heads, four sculptures, two objects (a chair, a pin) as well as sixteen ears. These ear photos were taken by Alphonse Bertillon who was a criminologist. More precisely, he was the creator of judicial anthropometry: in 1882 he founded the first criminal identification laboratory in France.

Michel Poivert explains: “The iconography of criminal anthropology makes an incursion here at the very moment when the group seeks to define a revolutionary identity.” The surrealists were very interested in the grammar of repression. Dalí, in particular, was passionate about the journal La Nature, a popular science journal which published at least three articles by Bertillon, illustrated with forensic photographs. The photographic fragments used by Dalí are in fact extracted from synoptic tables or tabbed directories by Bertillon. Bertillon’s ambition was to draw up an atlas of human morphology. What modern police was developing is therefore the transformation of the human body into a territory of surveillance and control. Bertillon reduces the body to a set of records.

Michel Poivert underlines that the repetition of the motif of the ear acts in the manner of a «stéréotypie», that is to say of a gesture reproduced in a loop or of a word reiterated without end: the symptom of a mental disorder. What’s closer to ecstasy than a morbid or hysterical fixation? From this point of view, certainly, the judicial photos of ears have their place perfectly in this photomontage, “which precisely mixes devotion and the disciplinary in the pathological figure of ecstasy,” suggests Michel Poivert: Dali’s passion for hysteria inevitably guides us towards Jean-Martin Charcot. Indeed, at the time when Dalí was concerned about a representation of ecstasy, the definition of the phenomenon by theologians was entirely constructed in reaction against the popularization of hysterical ecstasy.

In the text entitled “The Phenomenon of Ecstasy” (published in Le Minotaure, 1933), Dalí himself explains in covert terms the reason for this choice: the ears are “always in ecstasy” he says, probably in allusion to their coiled shape. The ears are shaped like a fractal or vortex. They lead the eye through a whirlwind to their central point, the black orifice of the ear canal… But the photomontage is itself constructed in the manner of an ear, guiding the eye to the portrait of the woman in ecstasy.

The Phenomenon of Ecstasy shows a woman at the heart of the photomontage; she offers the ambiguous spectacle of a being carried away by an emotion of mixed suffering and joy; between the devotional universe of grace and the clinical one of madness. What passion is she devoted to? Terrestrial or celestial?

Dalé expressed it in these terms: “During ecstasy, at the approach of desire, pleasure, anxiety, all opinions, all judgments (moral, aesthetic, etc.) change dramatically. Every image, likewise, changes sensationally. One would believe that through ecstasy we have access to a world as far from reality as that of dreams. The repugnant can be transformed into desirable, affection into cruelty, the ugly into beauty, defects into qualities, qualities into black misery. (The Phenomenon of Ecstasy, 1933).

sources of the text: Libération & open edition journals