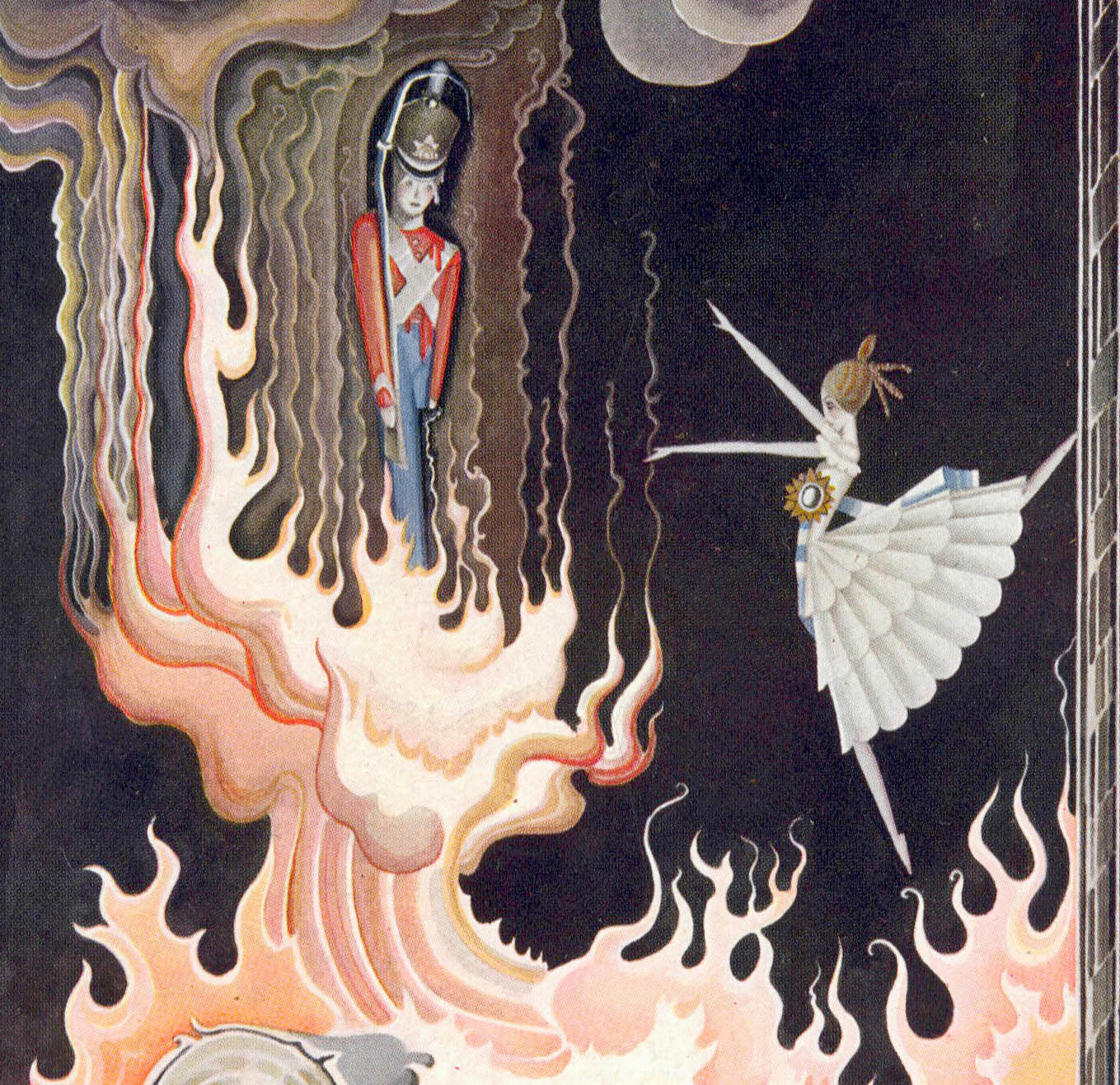

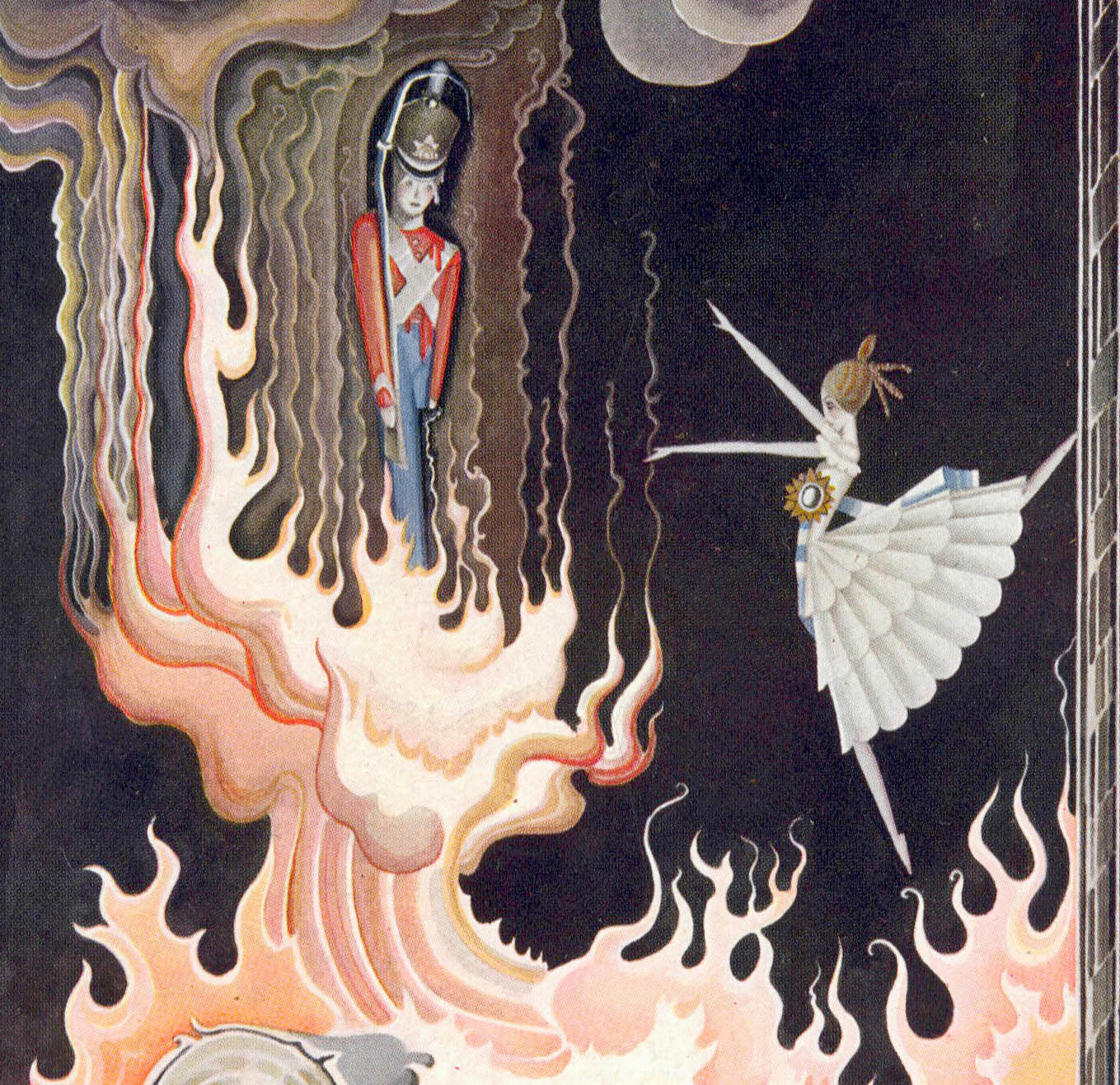

The draught of air caught the dancer, and she flew like a sylph just into the stove to the tin soldier. [The Tin Soldier and the Dancer ~ The Brave Tin Soldier ~ The Hardy Tin Soldier (1838)]

images that haunt us

The draught of air caught the dancer, and she flew like a sylph just into the stove to the tin soldier. [The Tin Soldier and the Dancer ~ The Brave Tin Soldier ~ The Hardy Tin Soldier (1838)]

You could spend hours marveling at Arthur Rackham’s work. The legendary illustrator, born on September 19, 1867, was incredibly prolific, and his interpretations of Peter Pan, The Wind in the Willows, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Rip Van Winkle (to name but a few) have helped create our collective idea of those stories.

Rackham is perhaps the most famous of the group of artists who defined the Golden Age of Illustration, the early twentieth-century period in which technical innovations allowed for better printing and people still had the money to spend on fancy editions. Although Rackham had to spend the early years of his career doing what he called “much distasteful hack work,” he was famous—and even collected—in his own time. He married the artist Edith Starkie in 1900, and she apparently helped him develop his signature watercolor technique. From the publication of his Rip Van Winkle in 1905, his talents were always in high demand.

He had the advantage of a canny publisher, too, in William Heinemann. Before the release of each book, Rackham would exhibit the original illustrations at London’s Leicester Galleries, and sell many of the paintings. Meanwhile, Heinnemann had the notion to corner multiple markets by releasing both clothbound trade books and small numbers of signed, expensively bound, gilt-edged collectors’ editions. When the British economy flagged, Rackham turned his attention to Americans, producing illustrations for Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and later Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination.

Pragmatic he may have been, but Rackham’s detailed work is pure fantasy, alternately beautiful, romantic, haunting, and sinister. Nothing he did was ever truly ugly, although he could certainly communicate the grotesque. And his illustrations are never cute, although his animals—as in The Wind in the Willows—have a naturalist’s vividness, and he could do whimsy (think Alice in Wonderland, or his many goblins) with the best of them. Several generations of children grew up with this nuanced beauty; it’s probably wielded even more of an aesthetic influence than we attribute to it.

Rackham once said, “Like the sundial, my paint box counts no hours but sunny ones.” This is peculiar when one considers the moodiness of much of his palate, and the unflinching darkness of many of his illustrations. I think, rather, of a quote from his edition of Brothers Grimm: “Evil is also not anything small or close to home, and not the worst; otherwise one could grow accustomed to it.” He made that evil beautiful, too, and it was this as much as anything that enchanted. By Sadie Stein for The Paris Review Blog

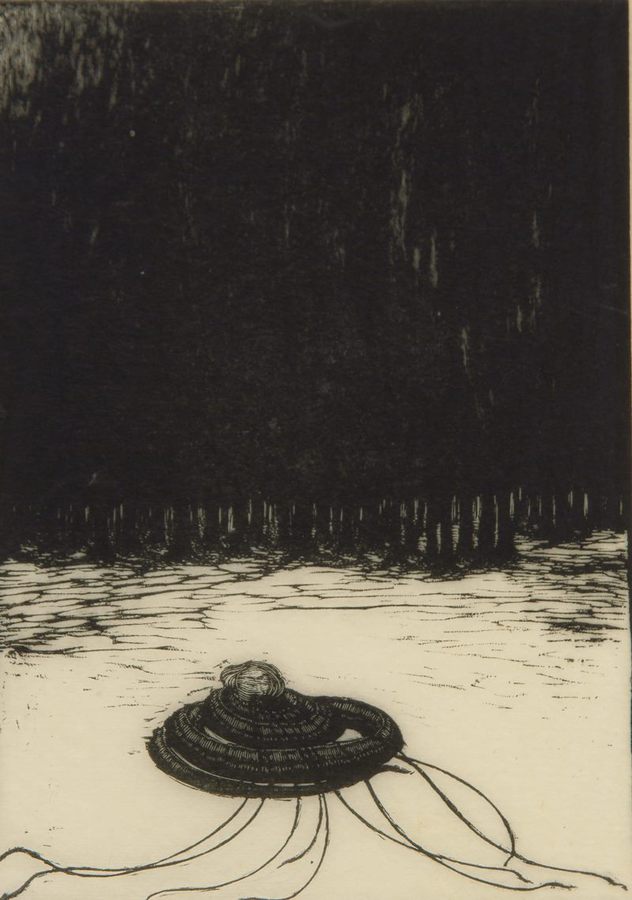

Franz Hanfstaengl :: Fairy

tale ball participants from the Künstlergesellschaft Jung München

artists association. An unidentified member and sculptor Hermann Oehlmann,

portraying the

Grimm Brothers’ race between the hare and the hedgehog, Munich, 1862

/ source: muenchner-stadtmuseum