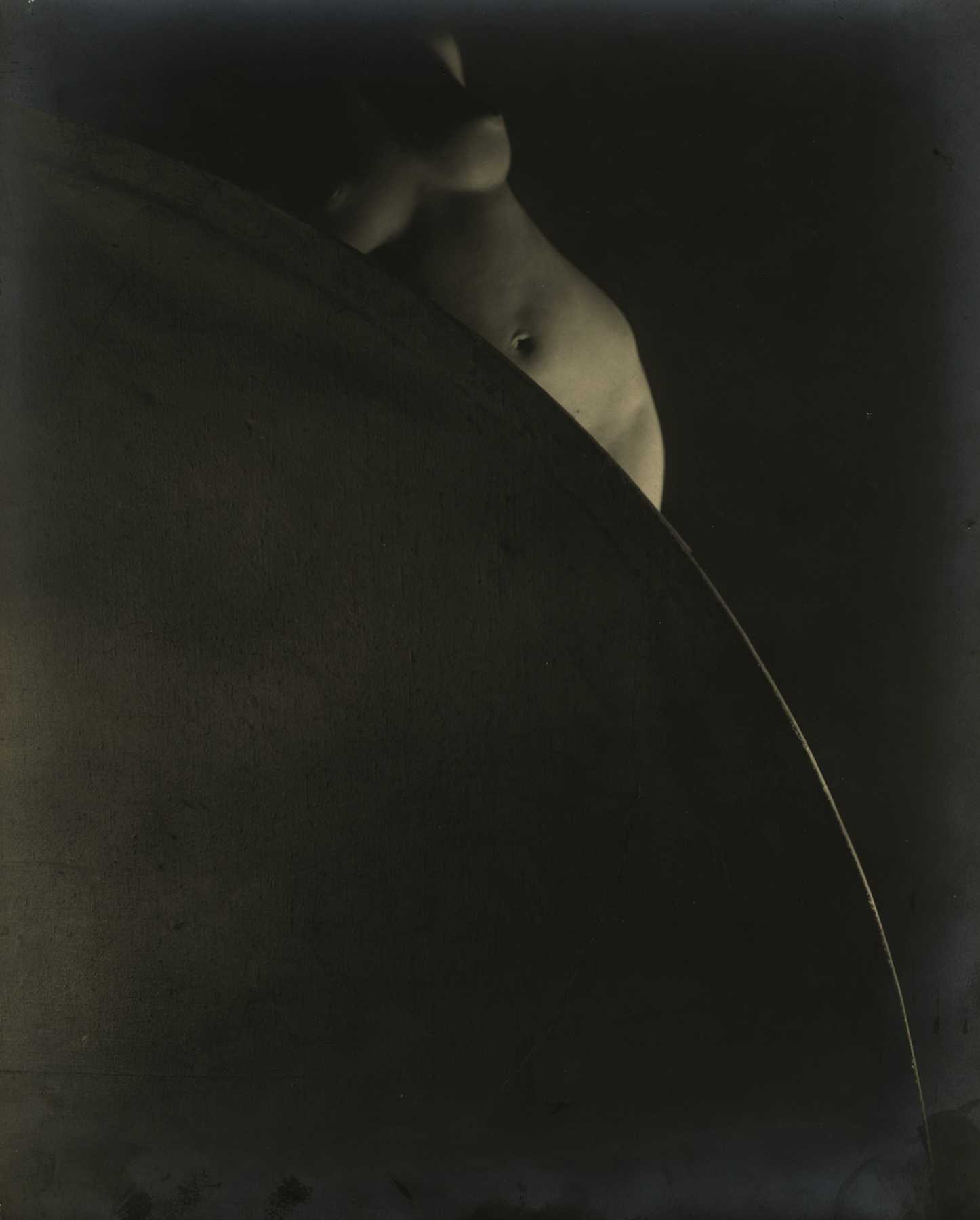

Nude with disk by Drtikol

images that haunt us

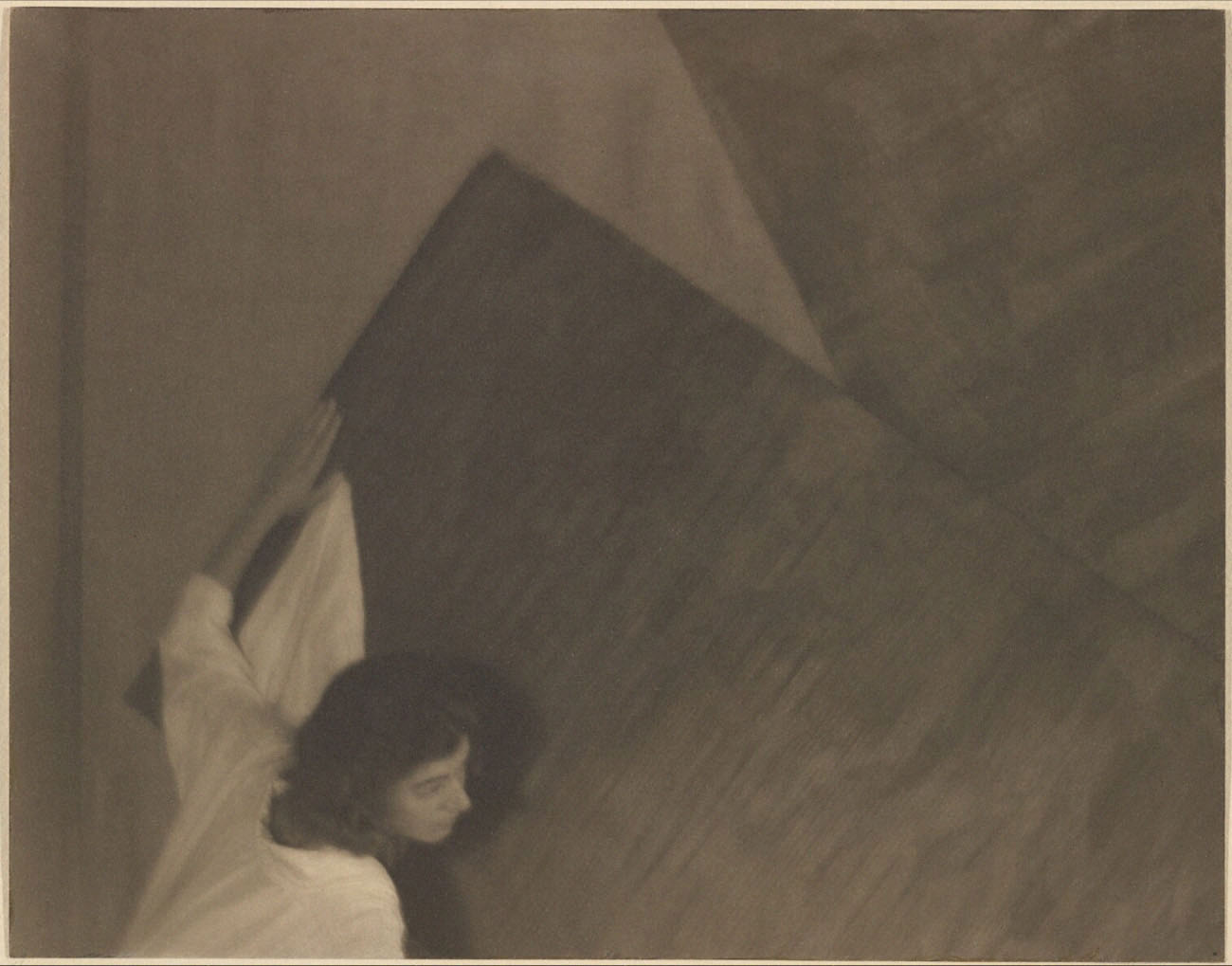

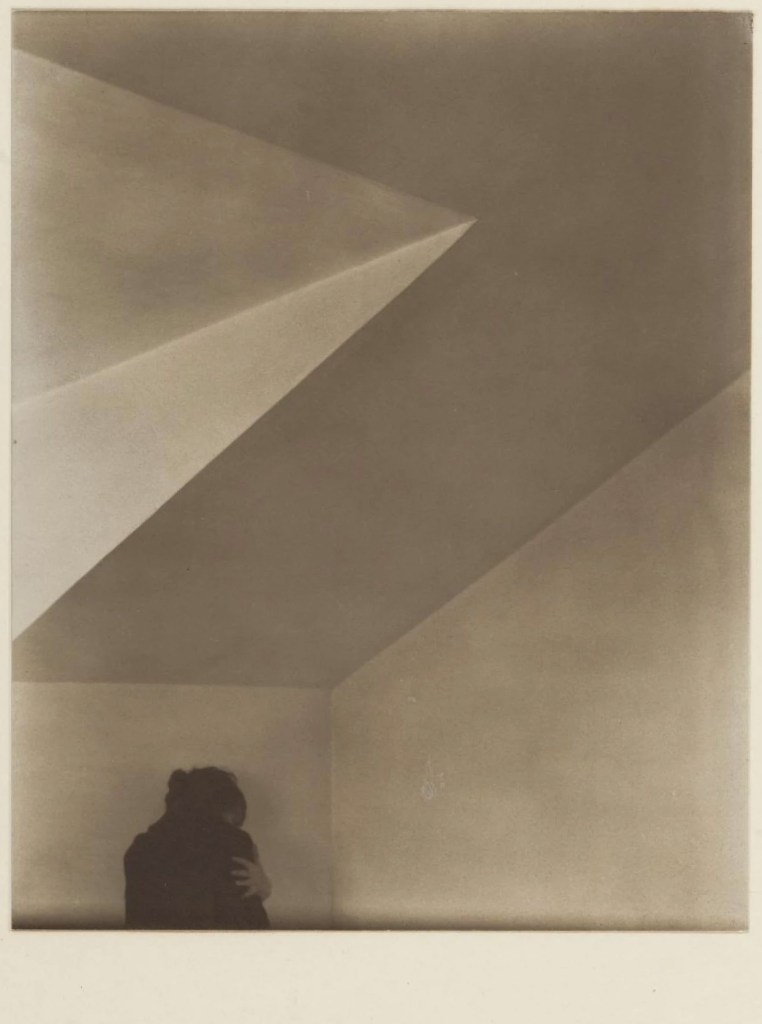

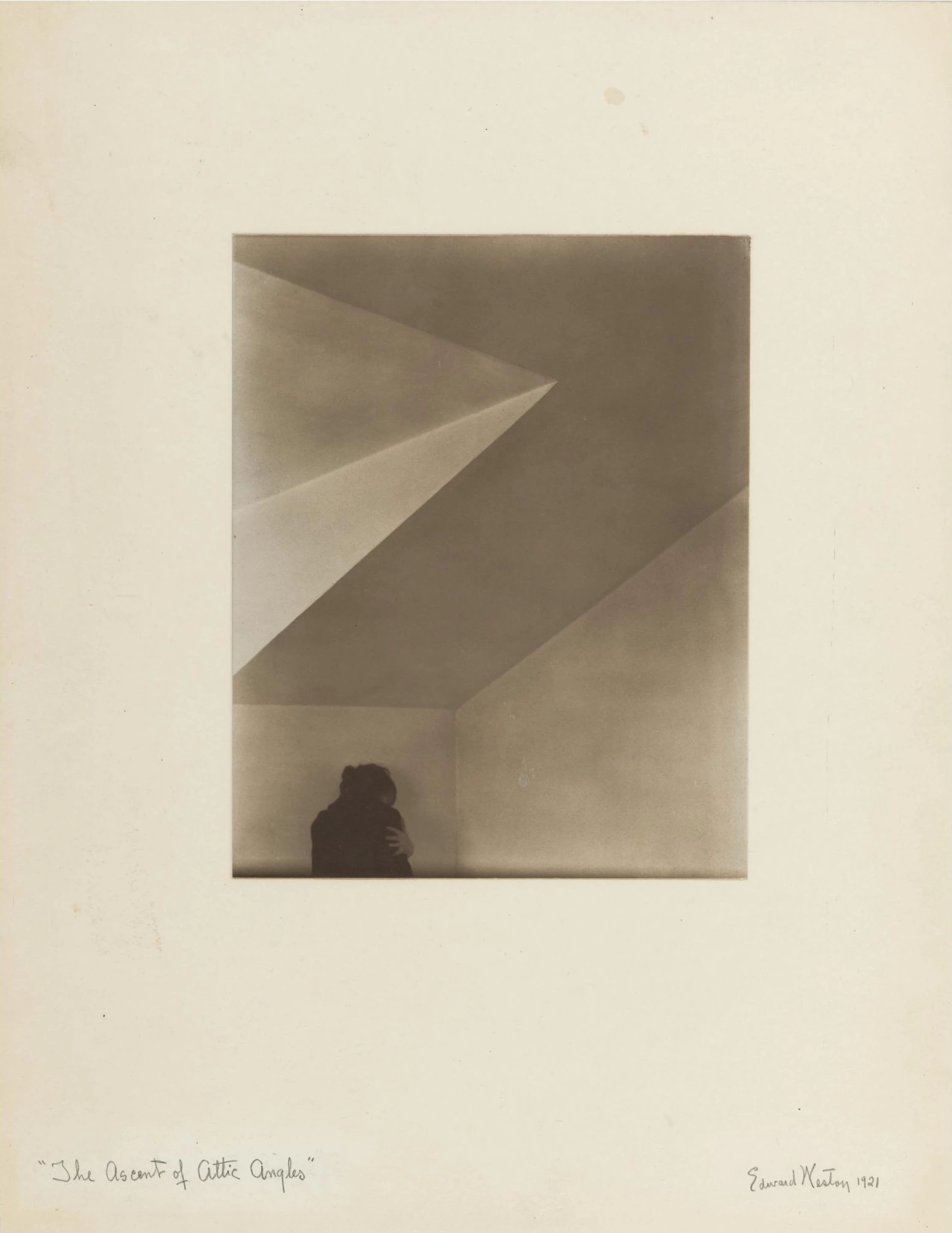

This particular photograph is part portrait and part compositional experiment with Weston’s growing interest in the formal concerns of Modernism. Katz is shown sitting in a niche where a network of large intersecting planes made up of the attic’s floor, walls, and dormers and articulated in varying shades by light entering from an unseen window on the right.

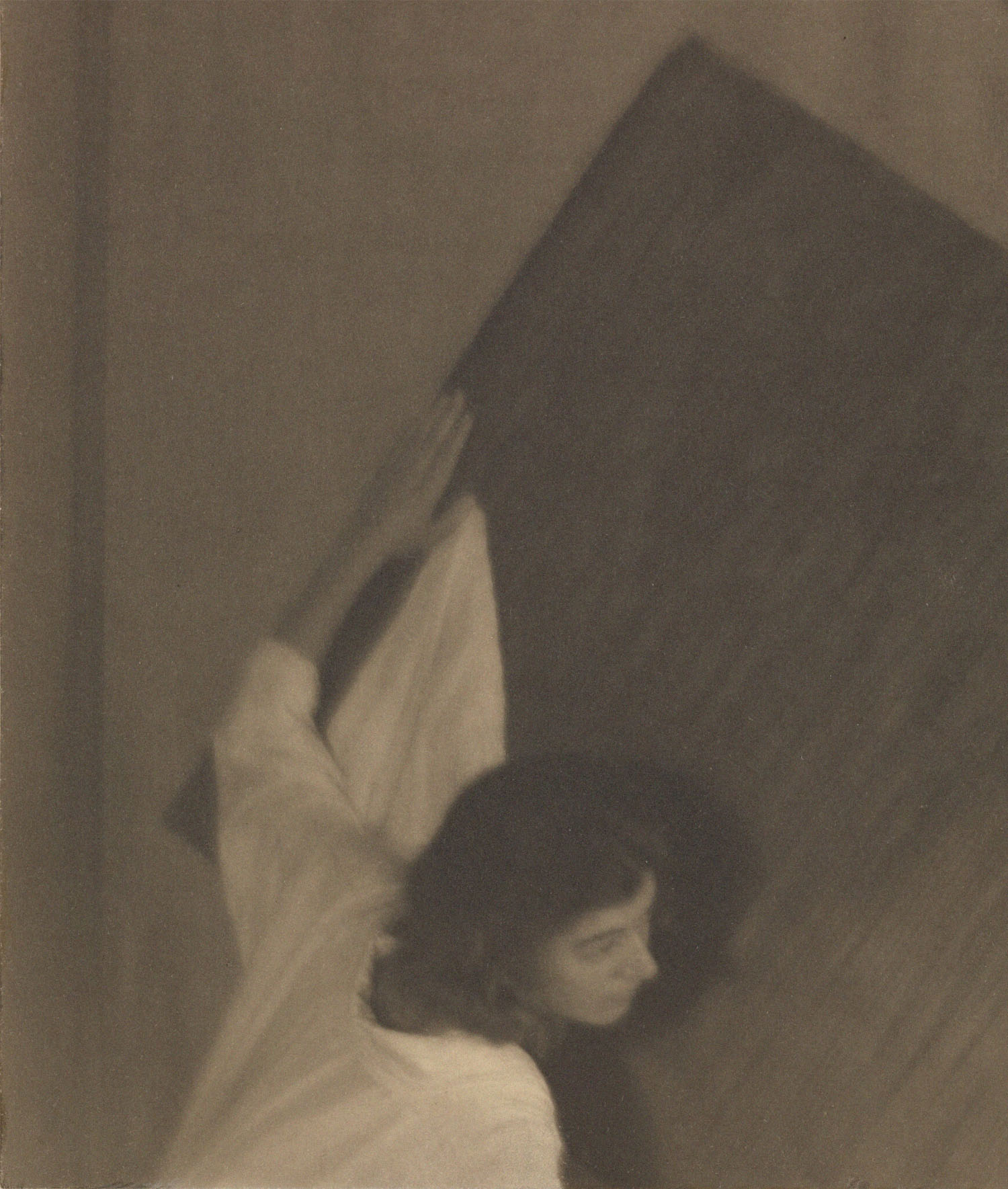

This particular photograph is Pictorialist in its soft focus and compositional arrangement. However, it is also Modernist in its self-conscious use of space and form as subjects of the photograph. Weston subordinated Katz’s figure to the graphic abstraction of the large rectangles that she appears to hold up. The print’s muted tones flatten the image’s depth, reducing the room to a two-dimensional space.

A critic for Pictorial Photography, wrote about this image: “Queerness for its own sake must have obsessed Edward Weston when he recorded the stiff and angular lines in Betty in Her Attic . . . , although there is no denying the truth and beauty of tones of the floors and walls. But the position of the girl!—is there not a touch of cussedness in that?”

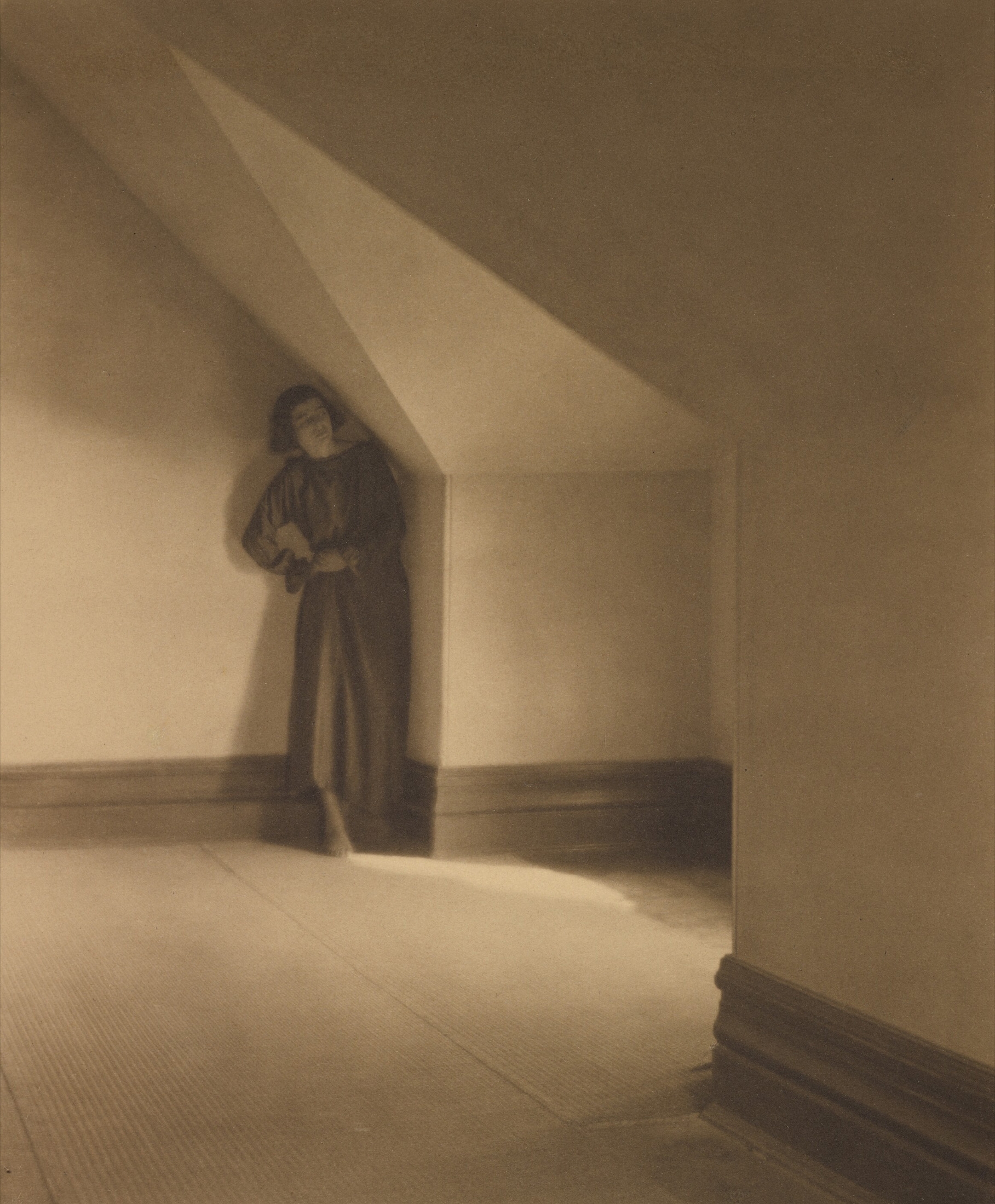

This particular photograph is part portrait and part compositional experiment with Weston’s growing interest in the formal concerns of Modernism. Katz is shown tucked into a network of large intersecting planes made up of the attic’s floor, walls, and dormers and articulated in varying shades by light entering from an unseen window on the left.

This particular photograph is part portrait and part compositional experiment with Weston’s growing interest in the formal concerns of Modernism. Katz is shown tucked into a network of large intersecting planes made up of the attic’s floor, walls, and dormers and articulated in varying shades by light entering from an unseen window on the right.

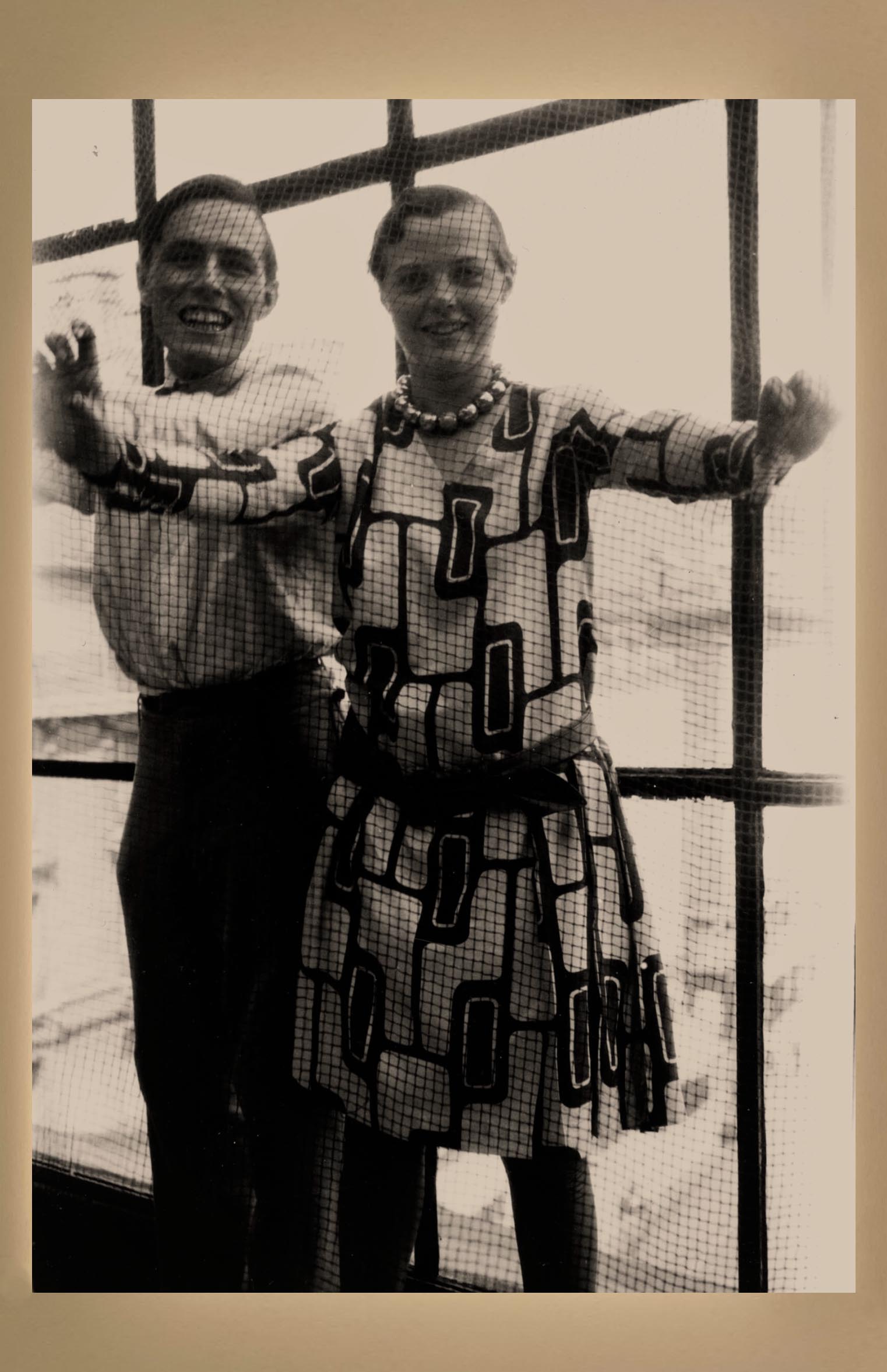

In 1920 Edward Weston began a creative series of pictures made in his friends’ attics. Reactions to these images were mixed. Imogen Cunningham (1883-1976), one of Weston’s friends and fellow photographers, wrote glowingly of one in a letter addressed to him, “It has Paul Strand’s eccentric efforts, so far as I have seen them, put entirely to shame, because it is more than eccentric. It has all the cubistically inclined photographers laid low. It is a most pleasing thing for the mind to dwell on, the mind I say and mean, not the emotions or fancies. It is literal in a most beautiful and intellectual way.”

The woman pictured is Betty Katz (later Brandner, 1895-1982), who was introduced to Weston by his colleague Margrethe Mather (1886-1952). Weston and Katz engaged in a brief affair in October 1920, when he made several other images of her in her attic and out on a balcony.

Text adapted from Brett Abbott. Edward Weston, In Focus: Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum [All quotes from this post retrieved from Getty museum]

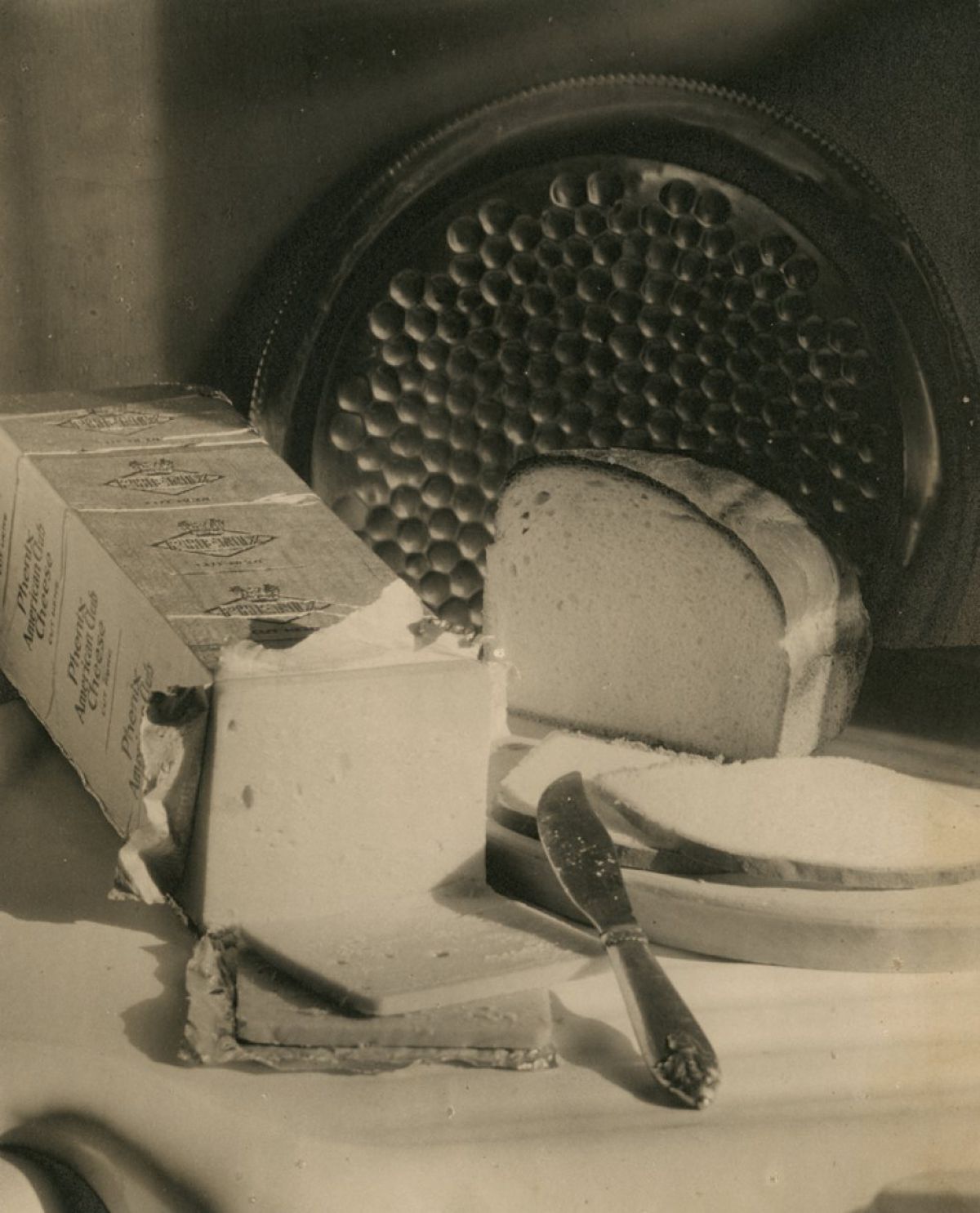

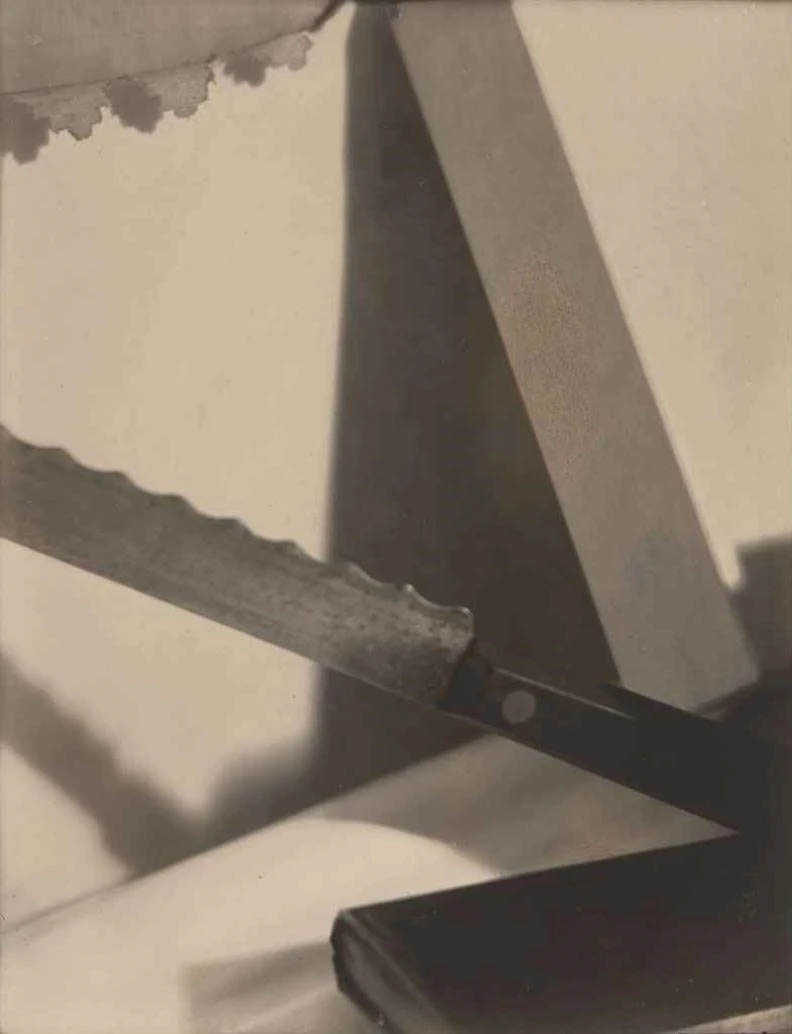

Watkins was likely influenced by Arthur Wesley Dow, a Columbia University professor of fine arts who was closely associated with the White school. Dow wrote about the beauty of compositions that use curved and straight lines, and alternating light and dark masses. Dow also promoted the ideas of Ernest F. Fenollosa, who believed that music was the key to the other fine arts since its essence was “pure beauty.” Watkins herself used music as a metaphor for visual patterning in an essay about the emergence of advertising photography out of painting: “Weird and surprising things were put upon canvas; stark mechanical objects revealed an unguessed dignity; commonplace articles showed curves and angles which could be repeated with the varying pattern of a fugue.” / Quoted from: Margaret Watkins: Of Sight and Sound (National Gallery of Canada)

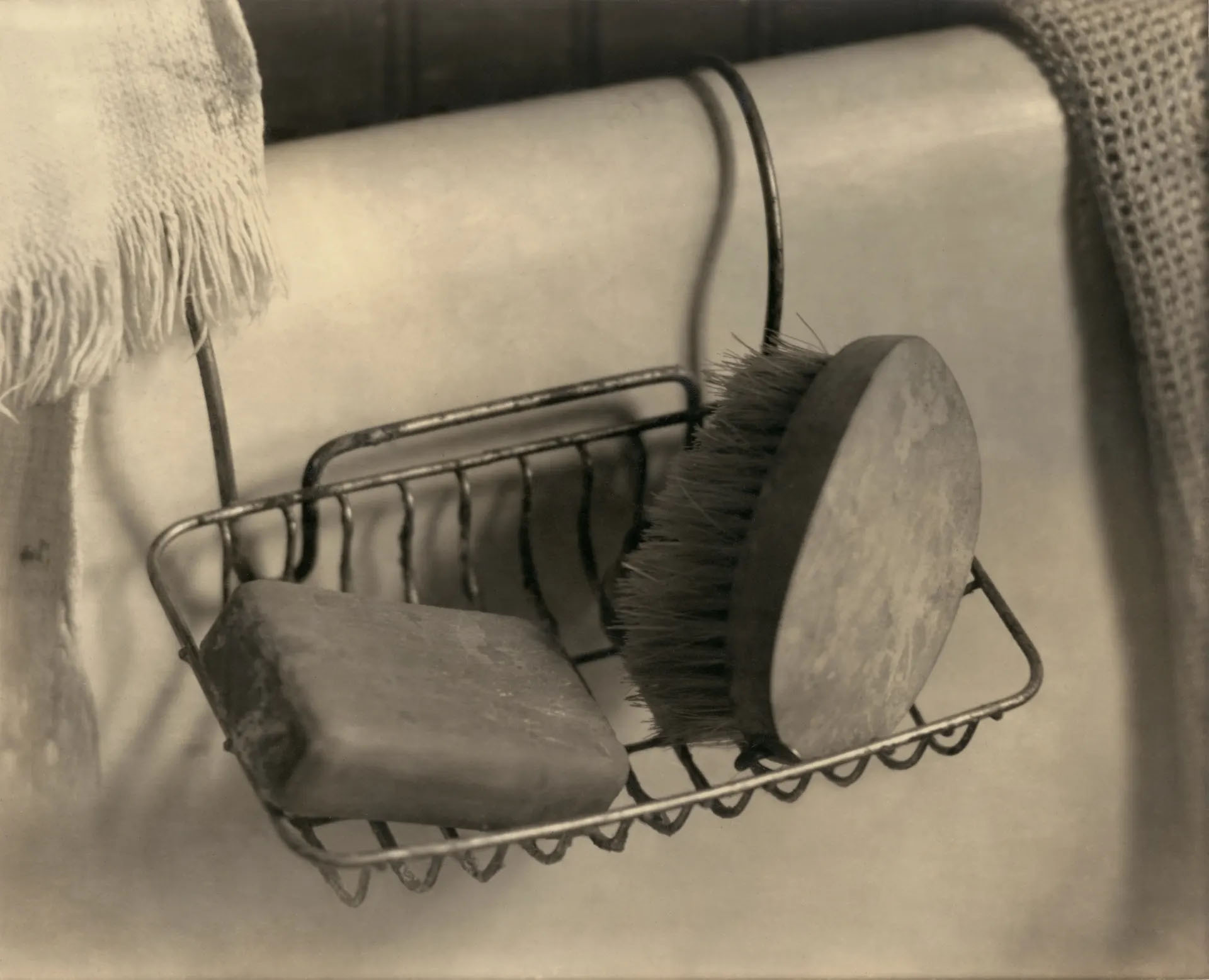

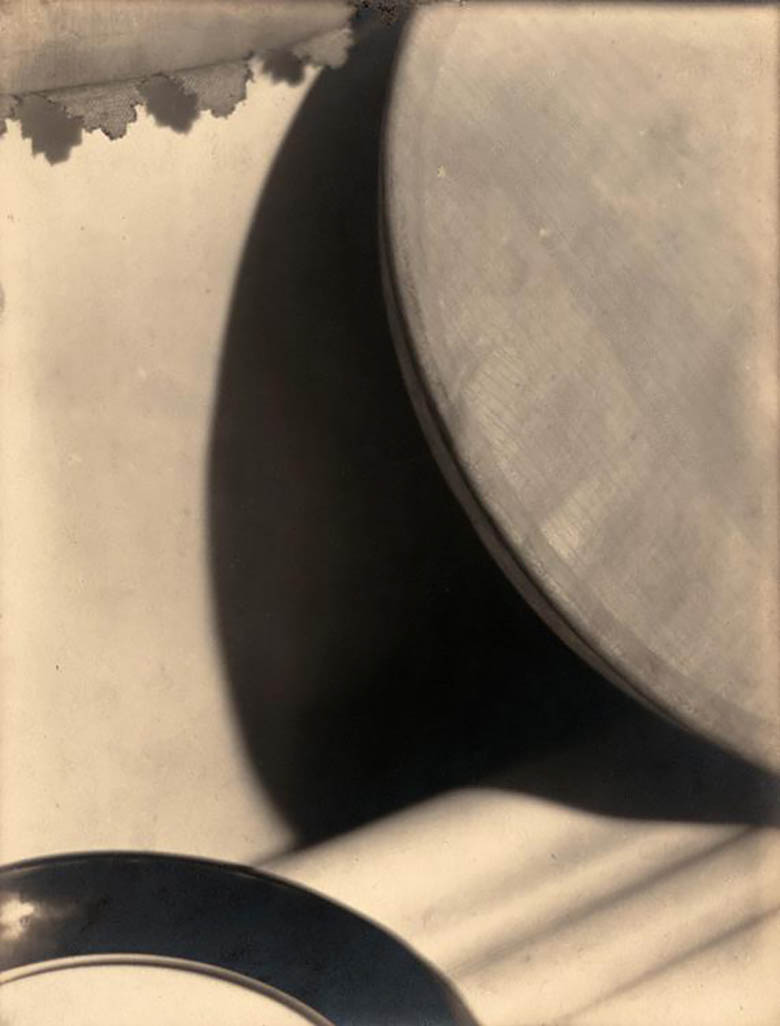

Margaret Watkins was a student at The Clarence H. White School of Photography in New York City. The school emphasized the principles of design that were common to all modes of artistic expression. This aesthetic, as seen here, resulted in works that merge realism and abstraction. Watkins received particular praise for her artistic transformation of the most common things: in this instance, the contents of her kitchen sink. / Quoted from The Nelson-Atkins Museum (x)

In 1919 Watkins made her first ground-breaking domestic still lifes, taking as her subject such mundane scenes as a kitchen sink and bathroom fixture. In Domestic Symphony, the graceful curve of the porcelain recalls the fern-like scroll of a violin. Again, the composition is striking: the lower three-quarters of the image is in darkness, anchoring the forms and volumes in the upper portion. / Quoted from: Margaret Watkins: Of Sight and Sound (National Gallery of Canada)

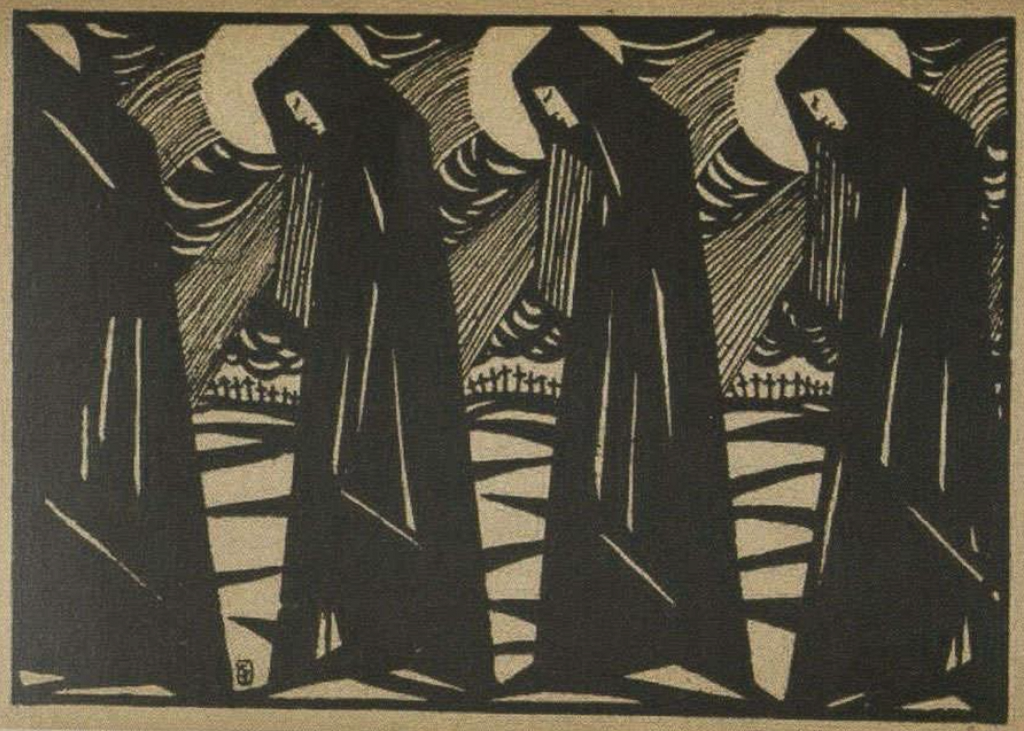

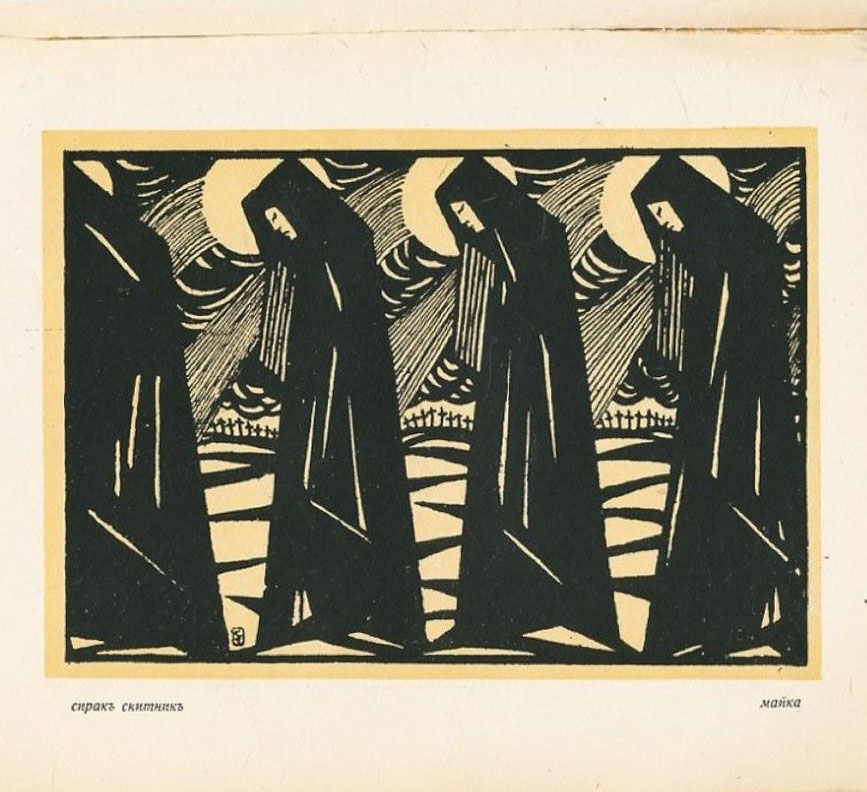

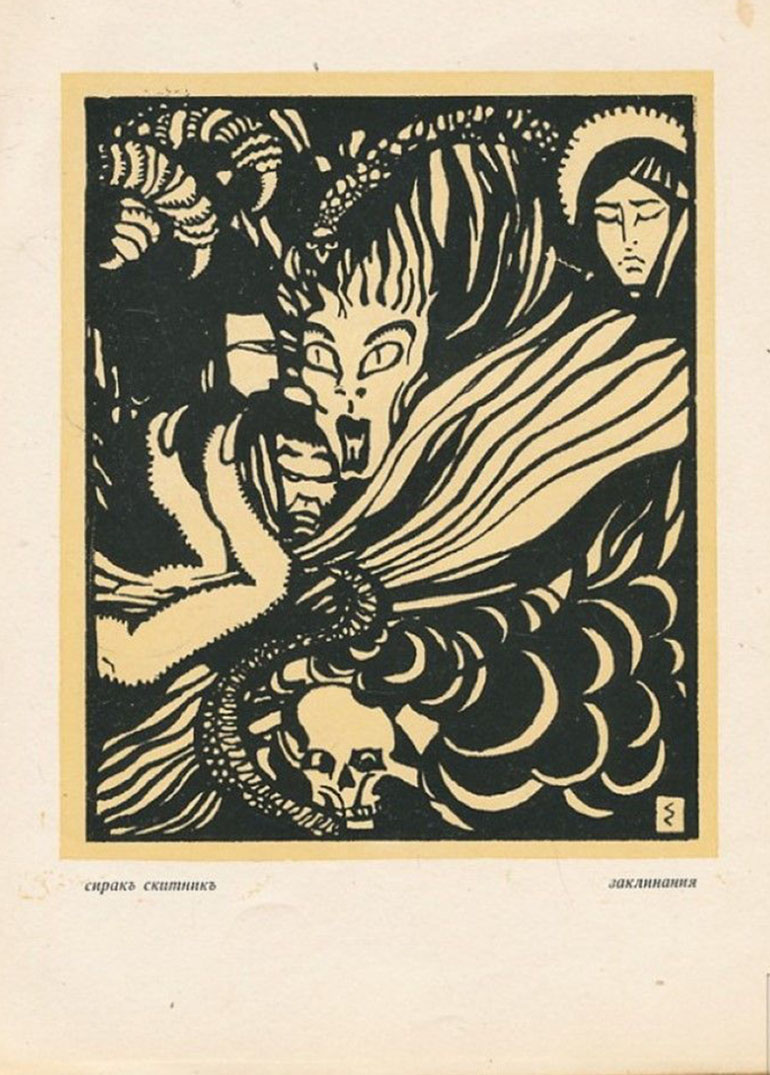

If you wish to learn more or read more about Sirak Skitnik and Bulgarian Modernism or Native Art, you may want to dig further here:

Modernism and the National Idea in Bulgaria @ sledva.nbu.bg (in English)

The whole batch of illustrations from the book are available to be viewed (but in very poor resolution) at the NYPL

Charlotte Perriand’s ball-bearings necklace was exhibited in 2009 at the exhibition “Bijoux Art Deco et Avant Garde” at the Musee Des Arts Decoratifs in Paris and, in 2011, in the show “Charlotte Perriand 1903-99: From Photography to Interior Design” at the Petit Palais. The necklace became, for a short period, synonymous with Perriand and with her championing of the machine aesthetic in the late 1920s and has subsequently attained the status of a mythical object and symbol of the machine age. This essay considers the necklace as an object and symbol in the context of modernist aesthetics. It also discusses its role in the formation of Perriand’s identity in the late 1920s, when she was working with Le Corbusier, and aspects of gender and politics in the context of the wider modern movement. [more on Semantic Scholar]

“I had a street urchin’s haircut and wore a necklace I made out of cheap chromed copper balls. I called it my ball-bearings necklace, a symbol of my adherence to the twentieth-century machine age. I was proud that my jewelry didn’t rival that of the Queen of England.”

Perriand had asked an artisan with a workshop in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine to make the piece out of lightweight chrome steel balls strung together on a cord. The piece was inspired by Fernand Léger’s still life “Le Mouvement à billes” (1926).

The necklace became a symbol of Perriand’s passion for the mechanical age […] (see also: Charlotte Perriand’s “Ball Bearings” Necklace on Irenebrination)

“Art is in everything,” insisted Charlotte Perriand. […] When you see Charlotte’s chaise longue, chair, and tables in front of that immense Léger, you cannot imagine the design without the art—it is a global vision.

On an adjacent wall, Collier roulement à billes chromées (1927)—a silver choker made from automotive ball bearings that Perriand not only designed but wore—is placed next to a Léger painting, Nature morte (Le mouvement à billes) (Still life [Movement of ball bearings], 1926). [quoted from William Middleton review of the exhibition Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World, on Gagosian]