Margo Lion dressed as a poodle

images that haunt us

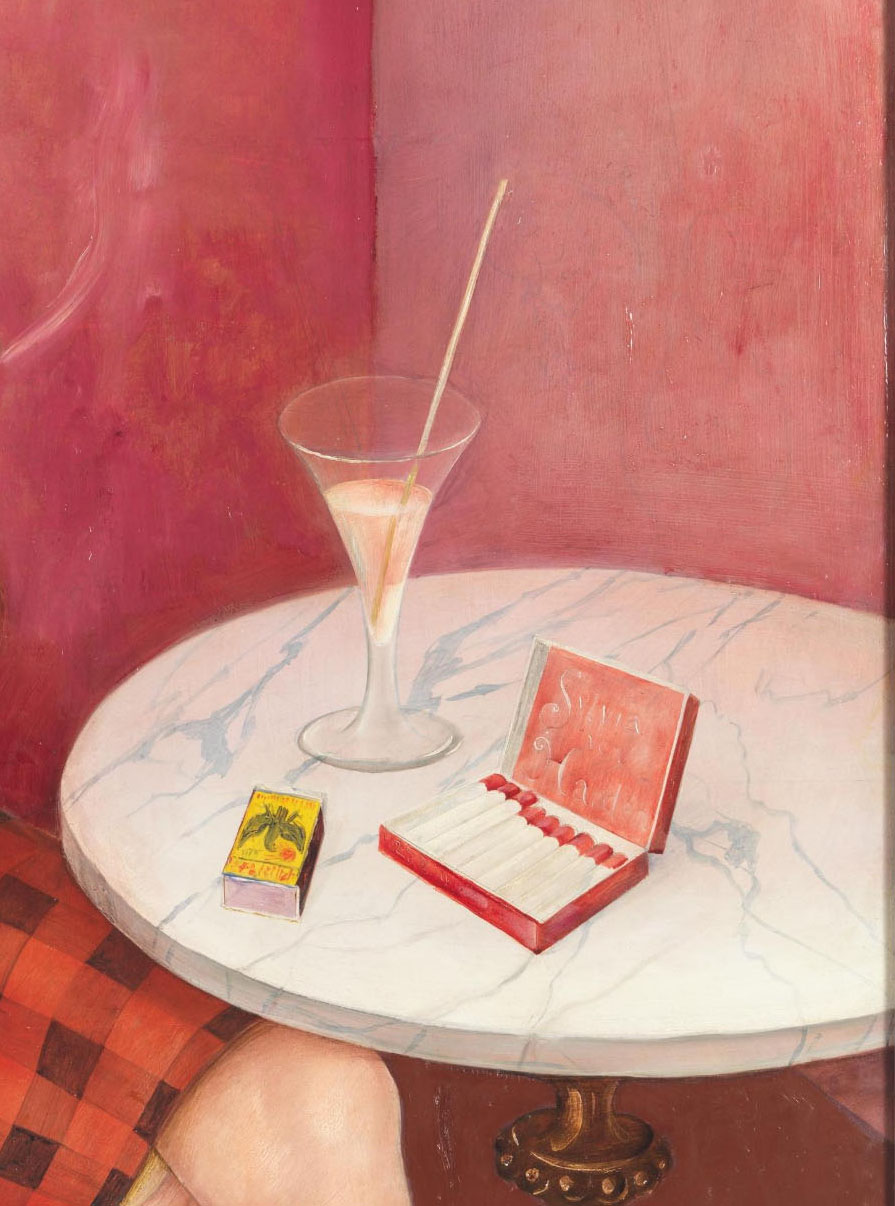

Journaliste à Berlin dans les années 1920, Sylvia von Harden (1894-1963) s’affiche en intellectuelle émancipée par une pose nonchalante. Otto Dix contrarie son arrogance par le détail d’un bas défait. Sa robe-sac à gros carreaux rouges détonne avec l’environnement rose, typique de l’art nouveau. Le style réaliste, froid et satirique est caractéristique du mouvement de la Nouvelle Objectivité [Neue Sachlichkeit] auquel appartient le peintre. Il s’inspire des maîtres allemands du début du 16e siècle (Grünewald, Cranach et Holbein), par la technique de la tempera sur bois et l’exhibition d’une intéressante laideur. | src Centre Pompidou

Sylvia von Harden (1894-1963) was a journalist in Berlin in the 1920s. Her nonchalant stance is a statement of her emancipated intellectual role. Otto Dix undermines her arrogance with the detail of a loose stocking and her rather awkward pose. Her red-checkered sack dress contrast with the pink environment, typically Art Nouveau. The cold, satirical realism typifies the New Objectivity [Neue Sachlichkeit] movement to which the painter belonged. lnspired by early 16th-century German masters (Grünewald, Cranach and Holbein), he embraced the tempera on wood panel technique as well as the choice to exhibit the ugliness. | src Centre Pompidou

Installé à Berlin entre 1925 et 1927, Dix peint une série de portraits remarquables. Maintes fois reproduit et exposé, celui de la journaliste Sylvia von Harden, de son vrai nom Sylvia Lehr (1894-1963), est l’un des plus fascinants. Il offre une véritable synthèse d’une recherche picturale qui s’inscrit dans ce que le critique Gustav Hartlaub désigne comme « l’aile gauche vériste » de la Neue Sachlichkeit [Nouvelle objectivité]. La représentation sans complaisance d’un type humain à travers ses attributs s’exprime dans le choix d’une intellectuelle émancipée des années 1920, aux allures masculines, fumant et buvant seule dans un café. […] L’image de la journaliste, que Dix a rencontrée au Romanische Café, haut-lieu berlinois du monde littéraire et artistique, reste pourtant ambiguë. Si dans ses souvenirs publiés à la fin des années 1950, la journaliste émigrée à Londres affirme que Dix l’a choisie pour son allure, représentative de cette époque, il semble que l’artiste la montre aussi en porte-à-faux par rapport à un type et un rôle dans lesquels elle paraît mal à l’aise. Sa pose nonchalante, mais peu naturelle, paraît trop ostentatoire ; son arrogance intellectuelle est contrariée par l’image de son bas défait ; et sa robe-sac à gros carreaux rouges l’oppose à l’environnement rose Art nouveau. Cette mise à nu semble avoir échappé au modèle. | src Centre Pompidou

Living in Berlin between 1925 and 1927, Dix painted a series of remarkable portraits. Reproduced and exhibited many times, that of the journalist Sylvia von Harden, whose real name was Sylvia Lehr (1894-1963), is one of the most fascinating. It offers a true synthesis of pictorial research which is part of what the critic Gustav Hartlaub designates as the “verist left wing” of the Neue Sachlichkeit [New Objectivity]. The uncompromising representation of a human type through its attributes is expressed in the choice of an emancipated intellectual from the 1920s, with masculine appearance, smoking and drinking alone in a café. […] The image of the journalist, whom Dix met at the Romanische Café, a Berlin hotspot for the literary and artistic world, nevertheless remains ambiguous. In her memories published at the end of the 1950s, the journalist who emigrated to London affirms that Dix chose her for her appearance, representative of that era, but it seems that the artist also shows her cantilevered from to a type and a role in which she seems uncomfortable. Her nonchalant, but unnatural pose seems too ostentatious; her intellectual arrogance is thwarted by the image of her undone stockings; and her large red check sack dress contrasts with the pink Art Nouveau environment. This exposure seems to have escaped the model.

Angela Lampe. Extrait du catalogue Collection art moderne – La collection du Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne , Paris, Centre Pompidou, 2007

Immediately after the First World War and the founding of the Weimar Republic, Joe May set up a gigantic project in his “Filmstadt” in Woltersdorf. Following the example of American and Italian monumental films and serials à la The Count of Monte Cristo, he brought out a series of eight consecutive, largely self-contained feature films at the end of 1919. His wife, the former operetta diva Mia May, played the leading role of the world traveler Maud Gregaard, who wants to take revenge on her father’s murderer and experiences all sorts of love and other adventures about it. The 5th part, in which Maud and her companion find the mysterious city of Ophir in the heart of Africa, is an adventure film that was staged with great effort – and May’s colleague Fritz Lang may have had to thank her for a few suggestions for Metropolis. [Deutsches Historisches Museum]

The large-scale film series about the adventuress Maud Gregaard, who becomes a modern »Countess of Monte Cristo« in eight parts, was produced in May 1919 and screened at weekly intervals at the end of the year. In Part 5, Maud, having just escaped from the natives of the Makombe tribe with her companion Madsen, ends up in the mysterious city of Ophir in Central Africa. There they mistake the high priests for the goddess Astarte, while Madsen is thrown to the slaves. With the help of the engineer Stanley, who is also enslaved, the trio finally finds the legendary treasure of the Queen of Sheba – and prepare their breakneck escape … A few kilometers outside of Berlin, in a gigantic studio recordings: Joe May’s “Filmstadt”, almost 30,000 people participated. [Film Archiv Austria]

Else Neuländer Simon, also known as Yva :: Painter Max Liebermann, Berlin, ca. 1928 | via kvetchlandia

Max Liebermann was a renowned Jewish painter, printmaker and long-time President of the Prussian Academy of Arts until he was forced from his position by the Nazis. While watching the Nazis stage their victory march through the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin following their assumption of state power in 1933, Liebermann said to a friend “Ich kann gar nicht soviel fressen, wie ich kotzen möchte” (I could not possibly eat as much as I would like to throw up).

more [+] by this photographer

Actress and dancer Anita Berber (1899 – 1928), 1910′s-1920′s. The daughter of a cabaret singer and a violinist, Anita Berber also follows an artistic path and studies theatre and dance from a young age. Appearing on several cabaret stages. She proposes audacious and provocative performances that portray violence, life and passion while she becomes the first dancer to execute her act entirely naked. / src: The Red List

more [+] Anita Berber posts