Les Jambes de Claire, ca. 1970

images that haunt us

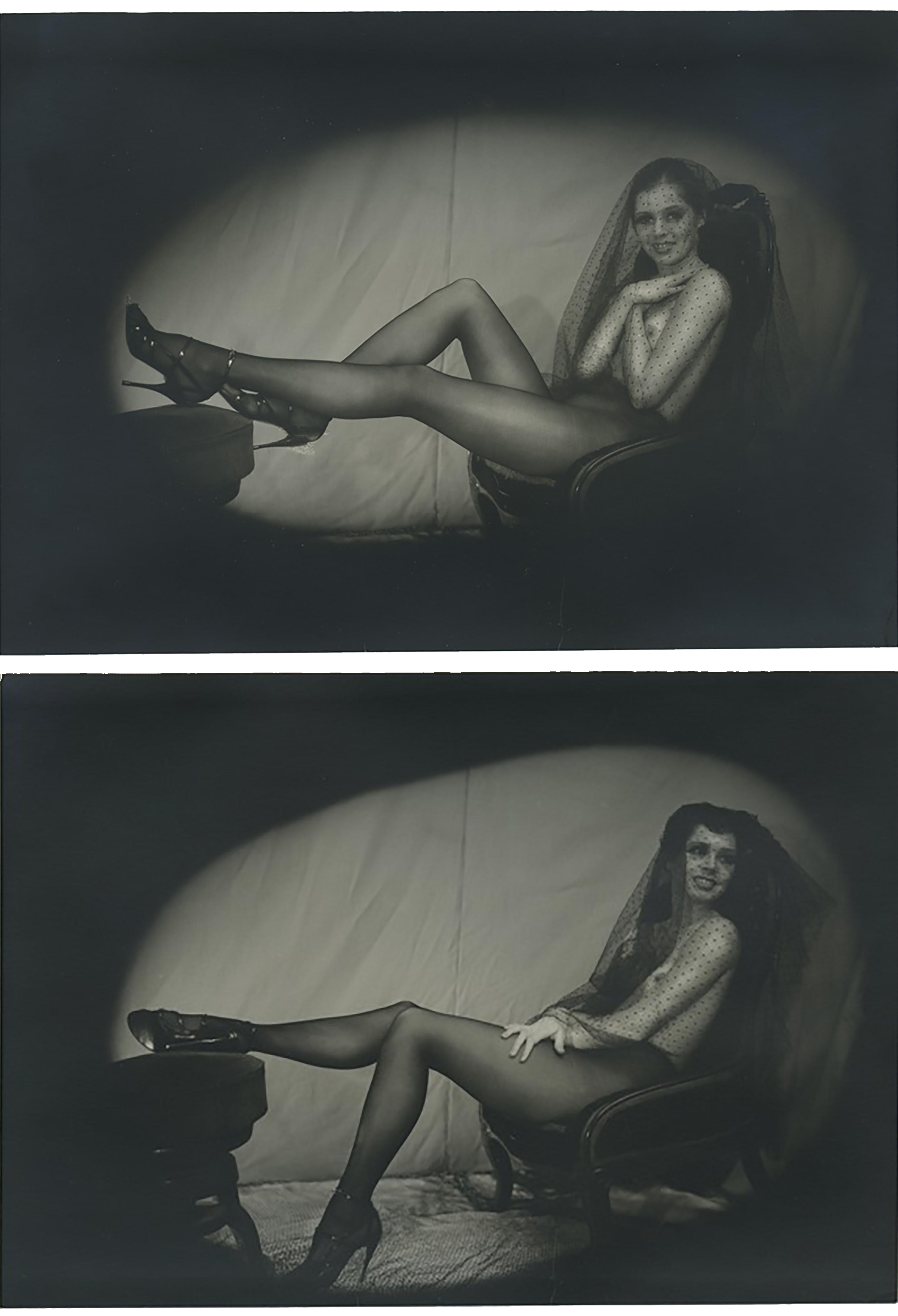

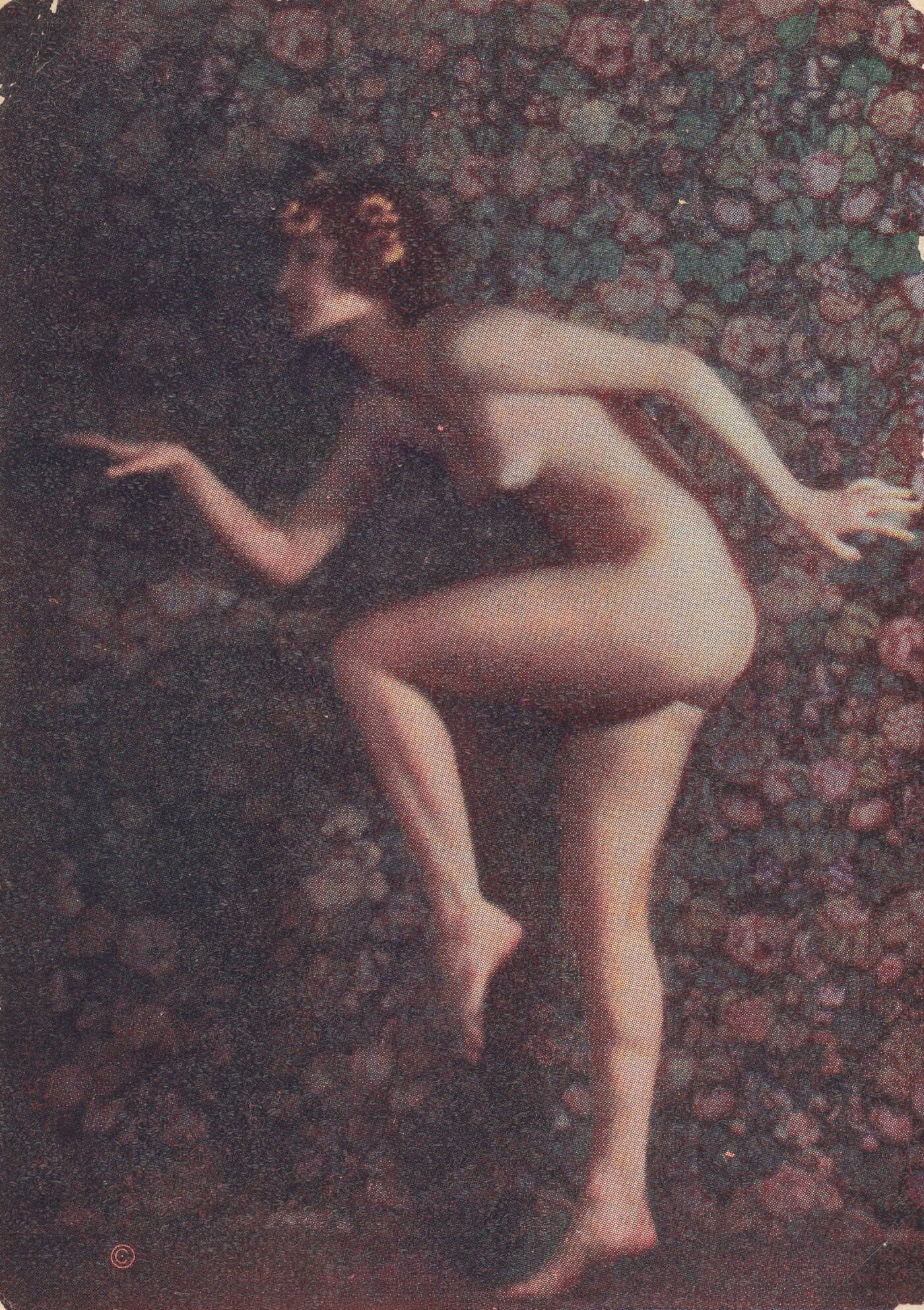

![Karl Struss (1886-1981) :: [Female nude]; ca. 1917. Hess-Ives print. Printed on mat board. | src Amon Carter Museum of American Art](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52583244407_4ffa2a0f6d_o.png)

Inscriptions on mount, verso:

u.l. to u.c. printed on mat board: [trimmed] OTOGR [trimmed] \ THE [trimmed] Corpora [trimmed] \ 1201 Race [St.] \ Philadelphia.P[a.]

Inscriptions on verso:

l.c. in blue ink: # 10

[stamp]: Original Photograph by Karl Struss \ From “The Female Figure.” \ First Series. Plate No. [in ink]: 16

[stamp]: Published & Copyrighted by F. Kotausek \ New York City

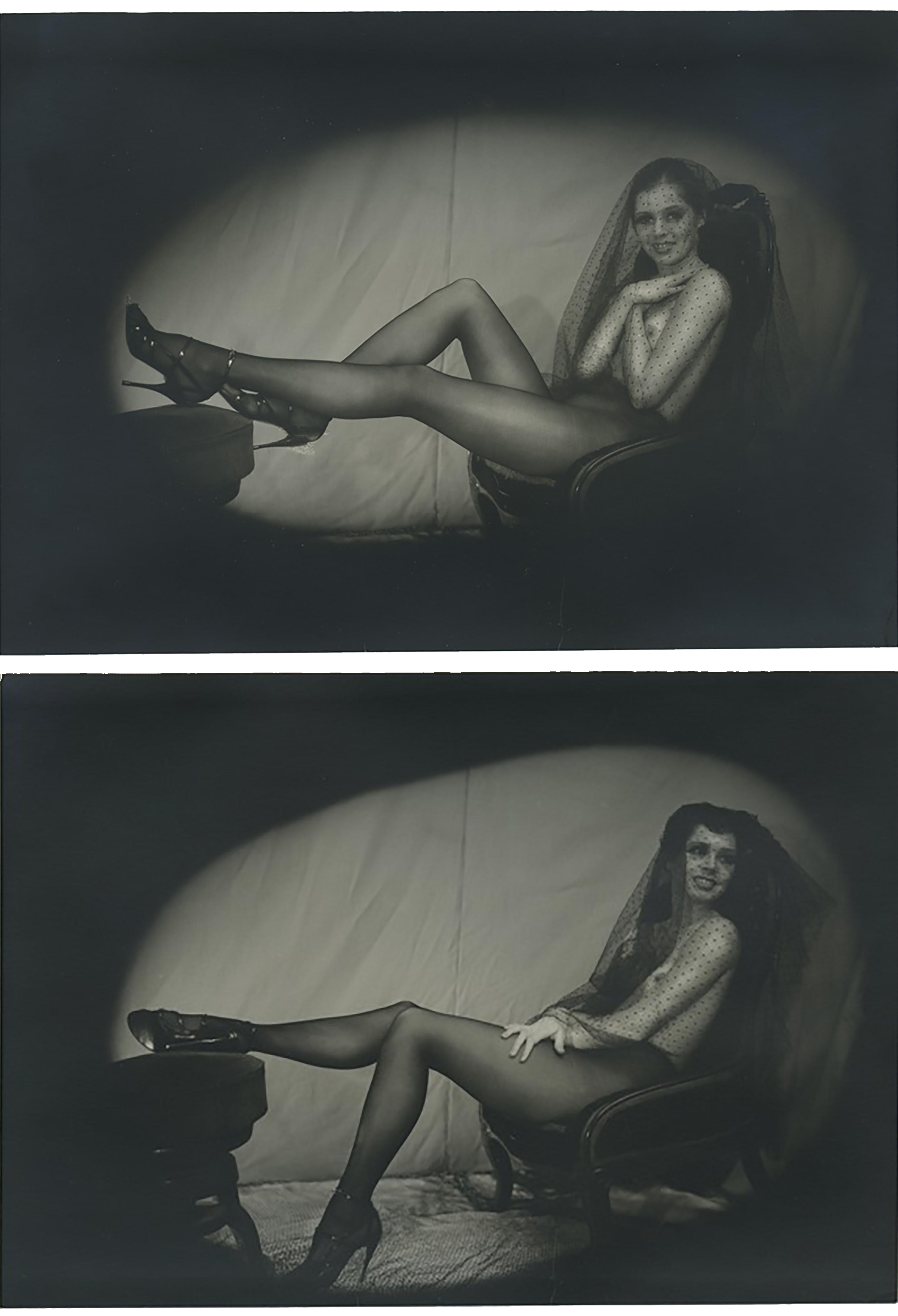

![Karl Struss (1886-1981) :: [Female nude], ca. 1917. Hess-Ives printt. | src Amon Carter Museum of American Art](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52584230768_7d7768d2d3_o.png)

Inscriptions on mount, verso:

u.l. to u.c. printed on mat board: First \ [trimmed] E \ [trimmed] GRAPH \ 1201 Race St. \ Philadelphia.Pa.

ANTIOS – this clearly legible and decorative signet is as much an effective design element of these famous portraits as EGON SCHIELE’s signature. For a long time, it seemed no one was interested in the fact that this legendary Viennese painter and self-portraitist could not have produced such accomplished photographs without the cooperation of a partner who was a master of photographic technique. The way expressive movement blends with the demands of ”classic” portraiture, or the way graphic outline contrasts with the two-dimensional rendering of figures and garments – this cannot have been the work of an amateur.

An amateur he certainly was not, this Anton Josef Trčka, who contracted his own name to form the artistic trademark ANT(on) IOS(ef) during his third year of studies at the “Graphischen Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt” (Institute of Graphic Instruction and Experimentation) in Vienna. This specialized learning institute for photography and reproduction technology, the first of its kind worldwide, was founded in 1888 in the tradition of the commercial arts schools, and combined the demand for technical perfection with solid instruction of an artistic nature. The young Trčka found in Karel Novak (later the co-founder of a similar school in Prague that produced the likes of Sudek or Rössler) a teacher, who not only taught his students how to turn the idea of Pictorialism into professional practice, but also conveyed an understanding of classical portraiture and a love of contemporary painting. The level of Novak’s influence can be seen in the way artists such as Rudolf Koppitz or Trude Fleischmann, along with ANTIOS, remained true their life long to decorative design devices particular to their teacher.

Well before his Schiele and Klimt portraits, ANTIOS had experimented with compositions that were indebted to Jugendstil. The dynamic contours of his figures appear to be inspired by the work of those young dancers who, in the first decades of the 20th century, consciously distanced themselves from classical ballet. By 1924, Trčka had developed close friendships with several dancers, including Hilde Holger and Gertrud Bodenwieser, and these found expression in photographic dance studies, nudes and portraits, and even drawings and poems. During this period, he developed a portrait style that clearly sets him apart from what is generally considered to be the international avant-garde of the 1920’s, yet at the same time is far removed from the great amateur art photographers at the turn of the century. ANTIOS’s imagery – with its wonderfully circular compositions, the painterly reworking by the artist himself, and the integration of the image title and his signature – radiates a deeper melancholy stemming from a determination for perfection that stands diametrically opposed to the photographic goals of the ”Neues Sehen” movement.

As early as his student years, the young Trčka considered himself not only a photographer but also – or mainly! –a painter and poet. And he put these inclinations to use in the service of his intense interest in religion, theosophy and anthroposophy. His admiration for Rudolf Steiner was second only to his admiration for Otokar Brezina, a Czech Poet who at the turn of the last century, created a language based on religion and nature that turned against traditional poetry as well as the hated Austrian domination. Due to this conflict between his Czech roots and the Austrian identity forced (due to economic reasons) on him, and driven with missionary zeal for Anthroposophy, Anton Josef Trcka would be damned to a lifelong existence on the margins. He saw his photographs and paintings exhibited only once in his lifetime, his poetry was made public only through private readings. However, his few friends and admirers, such as Hilde Holger, found in his work something extraordinary that accompanied them in times of escape or emigration. (Text by Monika Faber) ~ quoted from Galerie Kicken Berlin

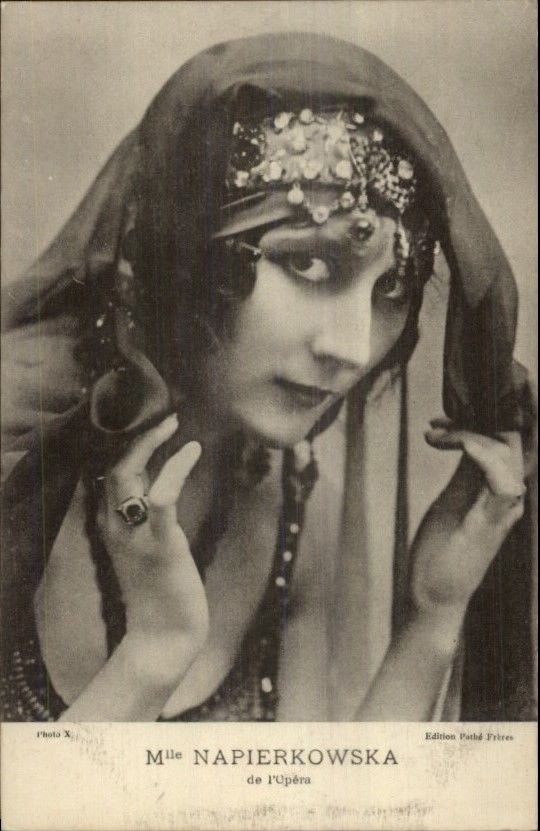

Charlotte Bachrach – auch Bara genannt – wird am 20. April 1901 in Brüssel als Tochter deutsch-jüdischer Eltern geboren; ihr Vater, Paul Bachrach, ist ein wohlhabender Textilhändler. Im Alter von sechs Jahren lernt Charlotte das Tanzen bei Jeanne Defaw, einer Schülerin der bekannten modernen Tänzerin Isadora Duncan (1877-1927). Später besucht sie in Lausanne die Schule eines anderen berühmten Tänzers, Choreographen und Pädagogen, des Russen Alexander Sacharoff (1886-1963). Zwei Begegnungen prägten sie massgeblich: die mit dem javanischen Prinzen Raden Mas Jodjana (1893-1972), einem mystischen Tänzer, bei dem Bara orientalischen Tanzunterricht nimmt, und die mit Uday Shankar (1900-1977), einem bengalischen Pionier des modernen Tanzes in Indien, der ihr indischen Tanz beibringt. Wichtig für ihren künstlerischen Werdegang ist schliesslich ihr Aufenthalt 1918 in Worpswede (Deutschland), wo sich die berühmte Künstlerkolonie befindet und wo viele Künstlerpersönlichkeiten weilen: unter den vielen, denen Charlotte begegnet, sind der Architekt Carl Weidemeyer (1882-1976) und der Maler Heinrich Vogeler (1872-1942), einer der Gründer der Kolonie 1889.

Die ersten öffentlichen Auftritte von Charlotte Bara gehen auf das Jahr 1917 in Brüssel zurück, wo sie sich durch ihren Pantomimentanz auszeichnet. Zwischen 1919 und 1920 erhält sie trotz ihres jungen Alters das Privileg, in einer Aufführung im Kammertheater von Max Reinhart an den Kammerspielen in Berlin zu tanzen; der Pianist Leo Kok begleitet sie am Klavier. In Berlin besucht sie die Kurse der Schweizerinnen Berthe Trümpy und Vera Skoronel. Anfang der 1920er Jahre zieht die Familie Bachrach endgültig nach Ascona, wo Paul Bachrach das Anwesen San Materno gekauft hat, ein antikes romanisches Herrenhaus, das einem französischen Grafen, Enrico De Loppinot, gehörte, umgeben von einem prächtigen botanischen Park mit Magnolien, Zitrusfrüchten, Palmen und Rosen. Seit den frühen Jahren im Schlösschen organisiert Charlotte Bara im grossen zentralen Saal Tanzvorführungen, Musik- und Literaturveranstaltungen. Sie beschliesst, neben dem Haus, dem sogenannten Castello San Materno, eine Tanzschule oder – in ihren Worten – “žeine Schule für Ausdrucksgestalt” zu bauen. Ein Theater also, das in ihren Vorstellungen der Idee eines Tanztempels entsprechen muss, gedacht als Sublimation einer neuen Lebensform. Um dieses Projekt zu realisieren, beruft Paul Bachrach seinen Freund und Architekten Carl Weidemeyer nach Ascona. Charlotte Bara lebt bis zu ihrem Tod am 7. Dezember 1986 in Ascona.

Charlotte Baras Choreographien sind mit dem religiösen und dem orientalischen Tanz verbunden. Besonders im sakralen oder religiösen Tanz lässt sich Bara von mittelalterlichen Legenden, Darstellungen der Passion Christi und heroischen Figuren des Christentums inspirieren (die berühmte Danza Macabra, in der Baras Tanz einen fast sakralen Charakter annimmt, verbindet kulturelle Einflüsse aus der Malerei der Frührenaissance und Renaissance und mittelalterlichen hagiographischen Legenden). Anfang der 1920er Jahre ist Gabriele D’Annunzio von der Intensität ihres Tanzes und den Bewegungen ihrer Hände so beeindruckt, dass er verspricht, ihr mit der Musik von Gian Francesco Malipiero eine Reihe von Legenden zu widmen. Anton Giulio Bragaglia widmet dem “žHeiligen Tanz” von Charlotte Bara eine eingehende Studie. Auch in den 1920er Jahren loben die Schriftsteller Ernst Blass und John Schikowski die Tänzerin und ihre harten und eckigen Bewegungen, ihre ausdrucksstarke und andächtige Intensität, ihren gotischen Stil. Charlotte Bara tanzt in Italien, Frankreich, Österreich und Deutschland, aber ihre Heimat bleibt immer Ascona, San Materno, wo sie im Frühjahr 1958 zum letzten Mal tanzt.

Der Charlotte Bara Bestand wird im Museo Comunale d’Arte Moderna aufbewahrt. Die Aufgabe des Museums ist es, die Dokumente zu studieren und die Bedeutung der Tänzerin im Zusammenhang mit der Entwicklung des modernen Tanzes herauszuarbeiten. (Quelle: Museo Ascona)

Charlotte Bachrach – also known as Bara – was born on April 20, 1901 in Brussels to German-Jewish parents; her father, Paul Bachrach, was a wealthy textile merchant. At the age of six, Charlotte learned to dance with Jeanne Defaw, a student of the well-known modern dancer Isadora Duncan (1877-1927). She later attended the school of another famous dancer, choreographer and teacher, Alexander Sacharoff (1886-1963), in Lausanne. Two encounters had a significant impact on her: that with the Javanese prince Raden Mas Jodjana (1893-1972), a mystical dancer from whom Bara took oriental dance lessons, and that with Uday Shankar (1900-1977), a Bengali pioneer of modern dance in India , who teaches her Indian dance. Finally, her stay in Worpswede (Germany) in 1918, where the famous artists’ colony is located and where many artistic personalities stay: among the many whom Charlotte meets were the proto-Bauhaus architect Carl Weidemeyer (1882-1976) and the painter Heinrich Vogeler (1872-1942), one of the founders of the colony in 1889; was important for her artistic career.

Charlotte Bara’s first public appearances date back to 1917 in Brussels, where she stood out for her pantomime dancing. Between 1919 and 1920, despite her young age, she received the privilege of dancing in a performance in Max Reinhart’s Kammertheater at the Kammerspiele in Berlin; the pianist Leo Kok accompanies her on the piano. In Berlin she attended the courses of Berthe Trümpy and Vera Skoronel. At the beginning of the 1920s, the Bachrach family permanently moved to Ascona, where Paul Bachrach bought the San Materno estate, an ancient Romanesque mansion that belonged to a French count, Enrico De Loppinot, surrounded by a magnificent botanical park with magnolias, citrus fruits, palm trees and roses. Since her early years in the castle, Charlotte Bara organized dance performances, music and literary events in the large central hall. She decides to build a dance school or – in her words – “a school for expression” next to the house, the so-called Castello San Materno. A theater that, in their ideas, must correspond to the idea of a dance temple, conceived as the sublimation of a new way of life. To realize this project, Paul Bachrach called his friend and architect Carl Weidemeyer to Ascona. Charlotte Bara lived in Ascona until her death on December 7, 1986.

Charlotte Bara’s choreographies are linked to religious and oriental dance. Particularly in sacred or religious dance, Bara is inspired by medieval legends, depictions of the Passion of Christ and heroic figures of Christianity (the famous Danza Macabra, in which Bara’s dance takes on an almost sacred character, combines cultural influences from early Renaissance and Renaissance painting and medieval hagiographic legends). At the beginning of the 1920s, Gabriele D’Annunzio was so impressed by the intensity of her dance and the movements of her hands that he promised to dedicate a series of legends to her with the music of Gian Francesco Malipiero. Anton Giulio Bragaglia devotes an in-depth study to Charlotte Bara’s “Holy Dance”. Even in the 1920s, the writers Ernst Blass and John Schikowski praised the dancer and her hard and angular movements, her expressive and reverent intensity, and her Gothic style. Charlotte Bara dances in Italy, France, Austria and Germany, but her home always remains Ascona, San Materno, where she dances for the last time in the spring of 1958.

The Charlotte Bara collection is kept in the Museo Comunale d’Arte Moderna. The museum’s mission is to study the documents and highlight the significance of the dancer in the context of the development of modern dance. (source: Museo Ascona)