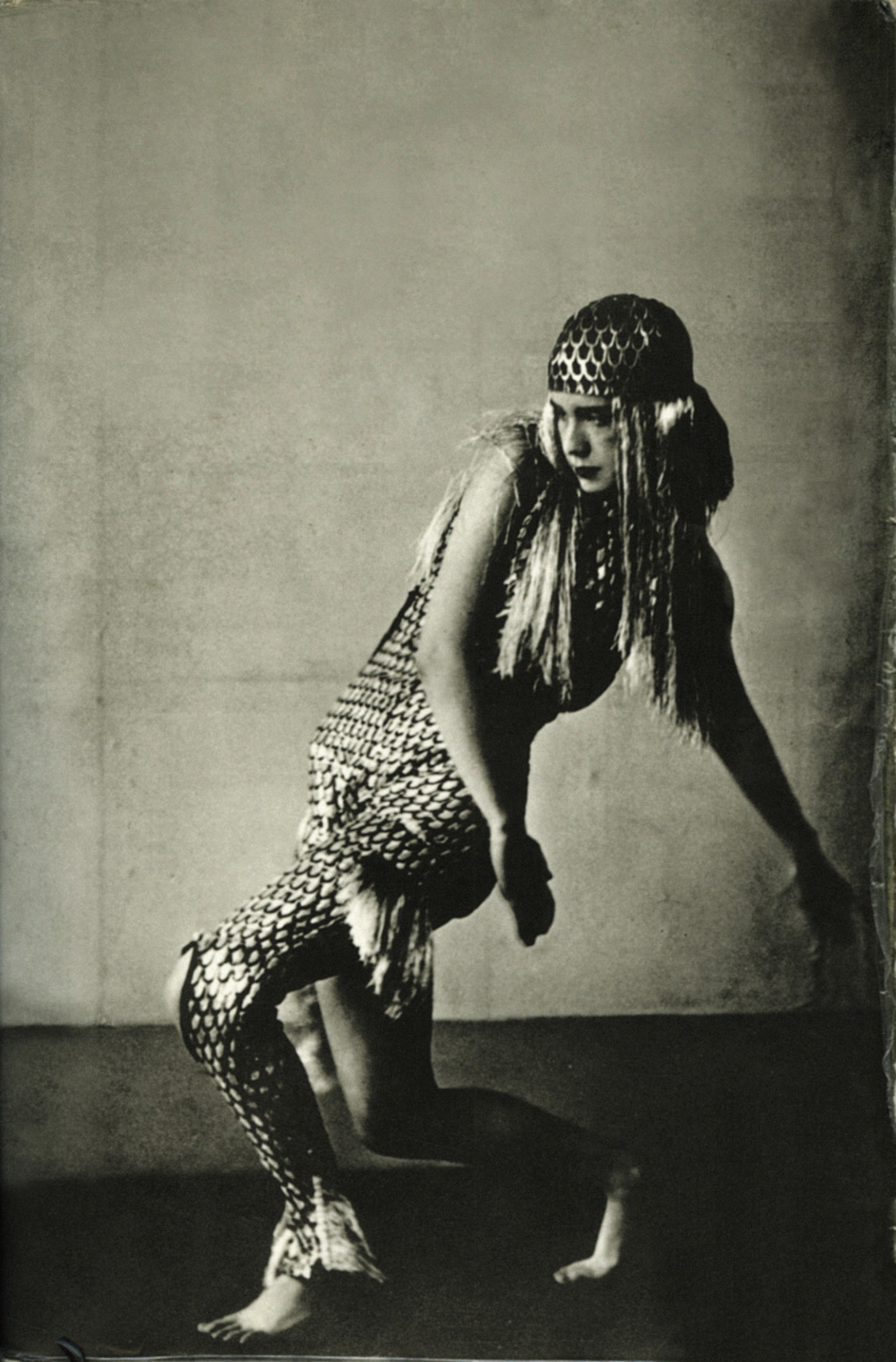

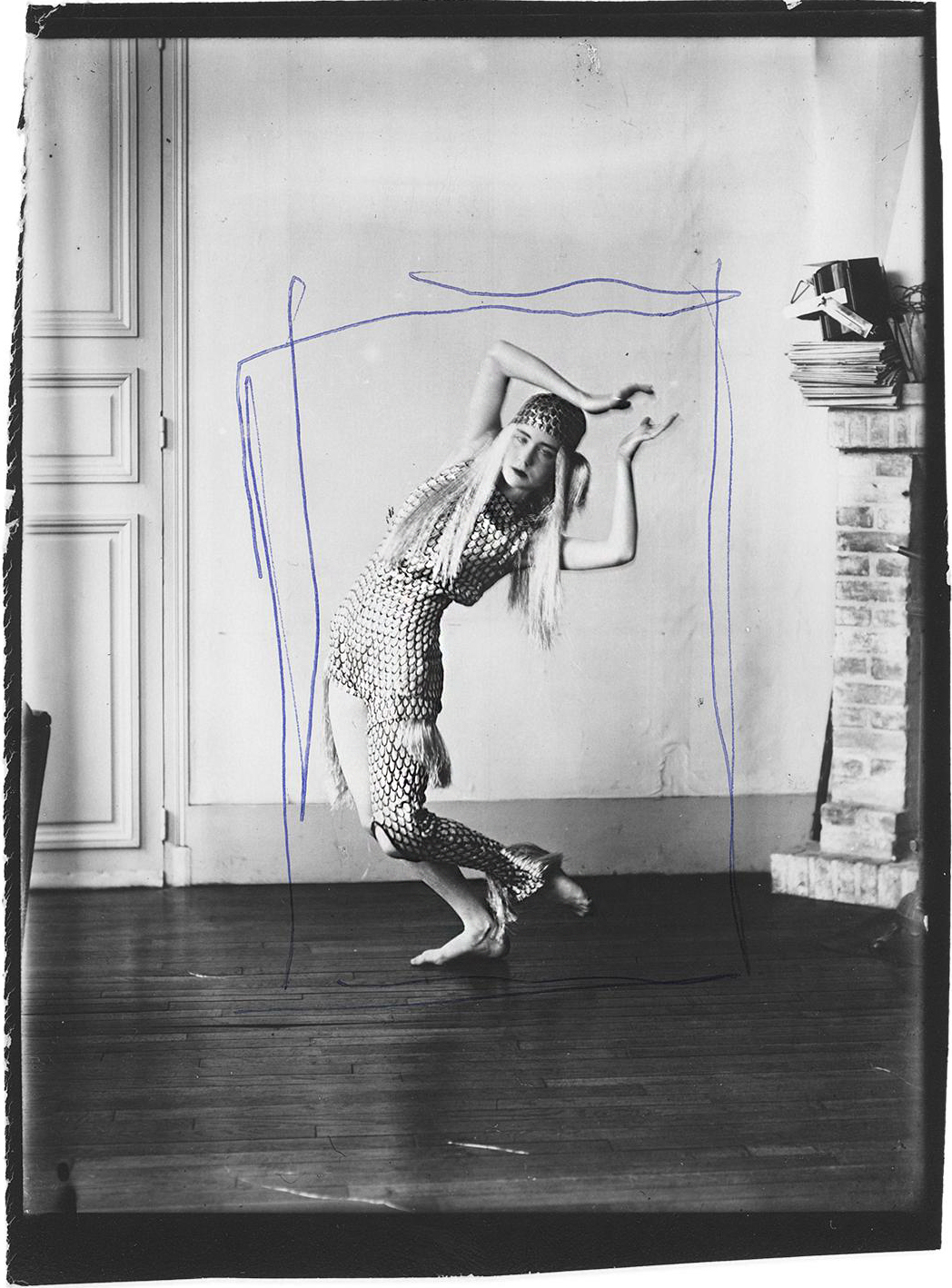

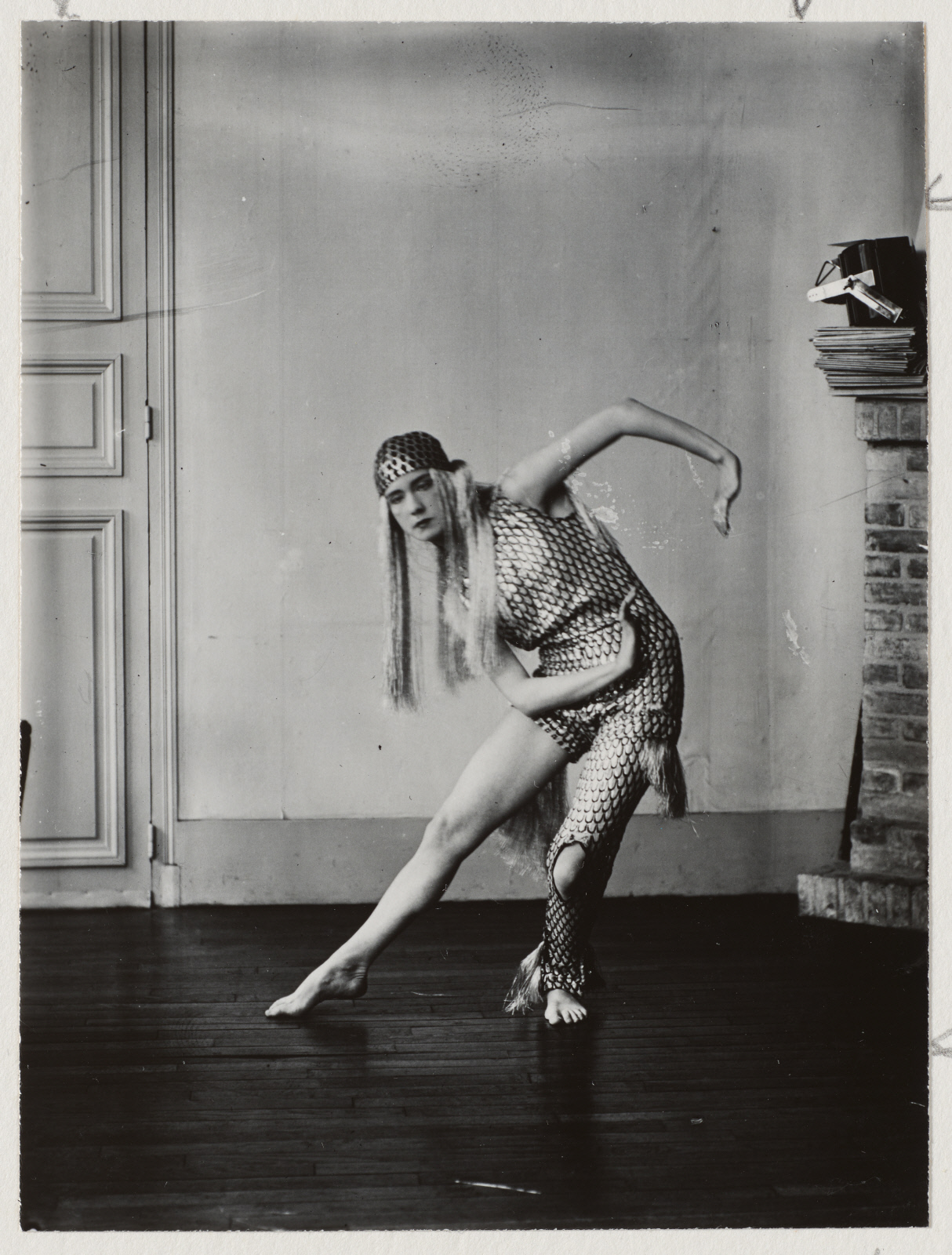

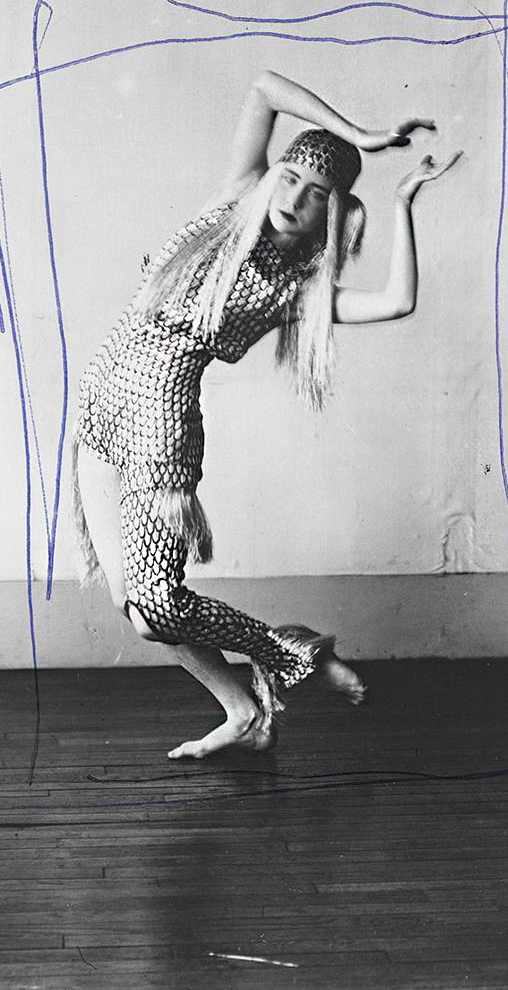

Strauss 1001 Nights · 1921

images that haunt us

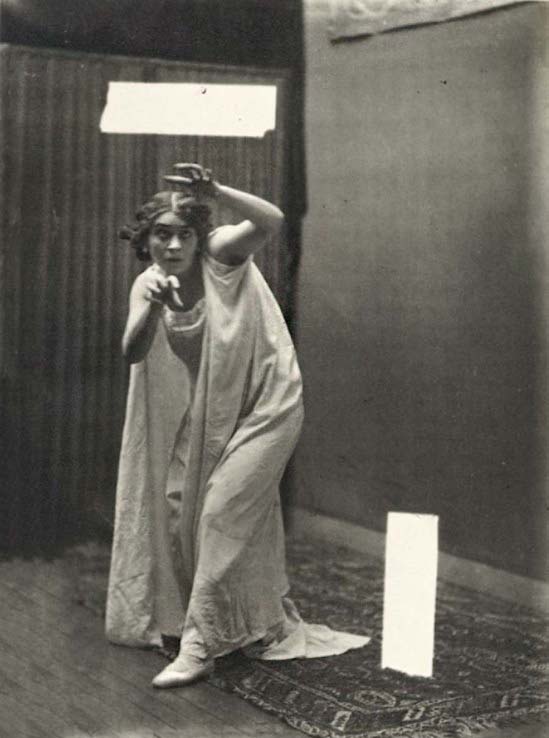

The life of James Joyce’s schizophrenic daughter Lucia requires no particular embellishment to move and amaze us. The “received wisdom,” writes Sean O’Hagan, about Lucia is that she lived a “blighted life,” as a “sickly second child” after her brother Giorgio. As a teenager, she “pursued a career as a modern dancer and was an accomplished illustrator. At 20, having abandoned both, she fell hopelessly in love with [Samuel] Beckett, a 21-year-old acolyte of her fathers.” He soon ended their one-sided relationship, an incident that may have triggered a psychotic break. Beckett was one of the few people to visit her later in the mental hospital where she died in 1982 after decades of institutionalization.

Before succumbing to her illness, Lucia was a highly accomplished artist who worked “with a succession of radically innovative dance teachers,” notes Hermione Lee in a review of a recent biography that “prove[s]… Lucia had talent.” Her promise renders her fall that much more dramatic, and her tragedy has inspired variously sensational biographies, plays, a novel and a graphic novel. Lucia perhaps provided a model for the language of Finnegans Wake. As Joyce once remarked, “People talk of my influence on my daughter, but what about her influence on me?”

The relationship between father and daughter has provided a subject of disturbing speculation, possibly warranted by Lucia’s “father-fixated… mental agonies,” as Stanford’s Robert M. Polhemus writes, and by “eroticized father-daughter, man-girl relationships” in Finnegans Wake that weave in Freud and Jung “with sexy nymphets on the couches of their secular confessionals.” At least in the excerpt Polhemus cites, Joyce uses the prurient language of psychoanalysis to seemingly express guilt, writing, “we grisly old Sykos who have done our unsmiling bits on ‘alices, when they were yung and easily freudened….”

Without inferring the worst, we can see the rest of this unsettling passage as parody of Jung and Freud’s ideas, of which, Louis Menand writes, he was “contemptuous.” And yet Joyce sent Lucia to see Carl Jung, “the Swiss Tweedledee,” he once wrote, “who is not to be confused with the Viennese Tweedledee.” His daughter’s behavior had become “increasingly erratic,” Lee writes, “she vomited up her food at table; she threw a chair at Nora [Barnacle, her mother] on Joyce’s 50th birthday… she cut the telephone wires on the congratulatory calls that friends were making about the imminent publication of ‘Ulysses’ in America; she set fire to things….”

After a succession of doctors and diagnoses and an “unwilling incarceration,” Jung agreed to analyze her. He had become acquainted with Joyce’s work, having written an ambivalent 1932 essay on Ulysses (calling it “a devotional book for the object-besotted white man”), which he sent to Joyce with a letter. Jung believed that both Lucia Joyce and her father were schizophrenics, but that Joyce, Menand writes, “was functional because he was a genius.” As Jung told Joyce biographer Richard Ellmann, Lucia and Joyce were “like two people going to the bottom of a river, one falling and the other diving.” Jung also, writes Lee, “thought her so bound up with her father’s psychic system that analysis could not be successful.” He was unable to help her, and Joyce reluctantly had her committed.

Much of the relationship between Joyce and his daughter remains a mystery because of the destruction of nearly all of their correspondence by Joyce’s friend Maria Jolas. (Likewise Beckett burned all of his letters from Lucia). This has not stopped her biographer Carol Loeb Shloss from writing about them as “dancing partners,” who “understood each other, for they speak the same language, a language not yet arrived into words….” What is clear is that “Joyce’s art surrounded” his daughter, “haunted her from birth,” and was part of the circumstances that led to her and her brother often living in extreme poverty and instability.

Lucia resented her father but was never able to fully separate herself from him after several failed relationships with other prominent figures, including American artist Alexander Calder. Whether we characterize her story as one of abuse or, as Lee writes of Shloss’ biography (Lucia Joyce: To Dance in the Wake), one of “love and creative intimacy,” depends on what we make of the limited evidence available to us. The erasure of Lucia from her father’s life began not long after his death, and hers “is a story that was not supposed to be told,” writes Shloss. But it deserves to be, as best as it can. Had her life been different, she would doubtless be well-known as an artist in her own right. As one critic wrote of her skills as a performer, linguist, and choreographer in 1928, James Joyce “may yet be known as his daughter’s father.” | quoted from: How James Joyce’s Daughter, Lucia, Was Treated for Schizophrenia by Carl Jung | openculture

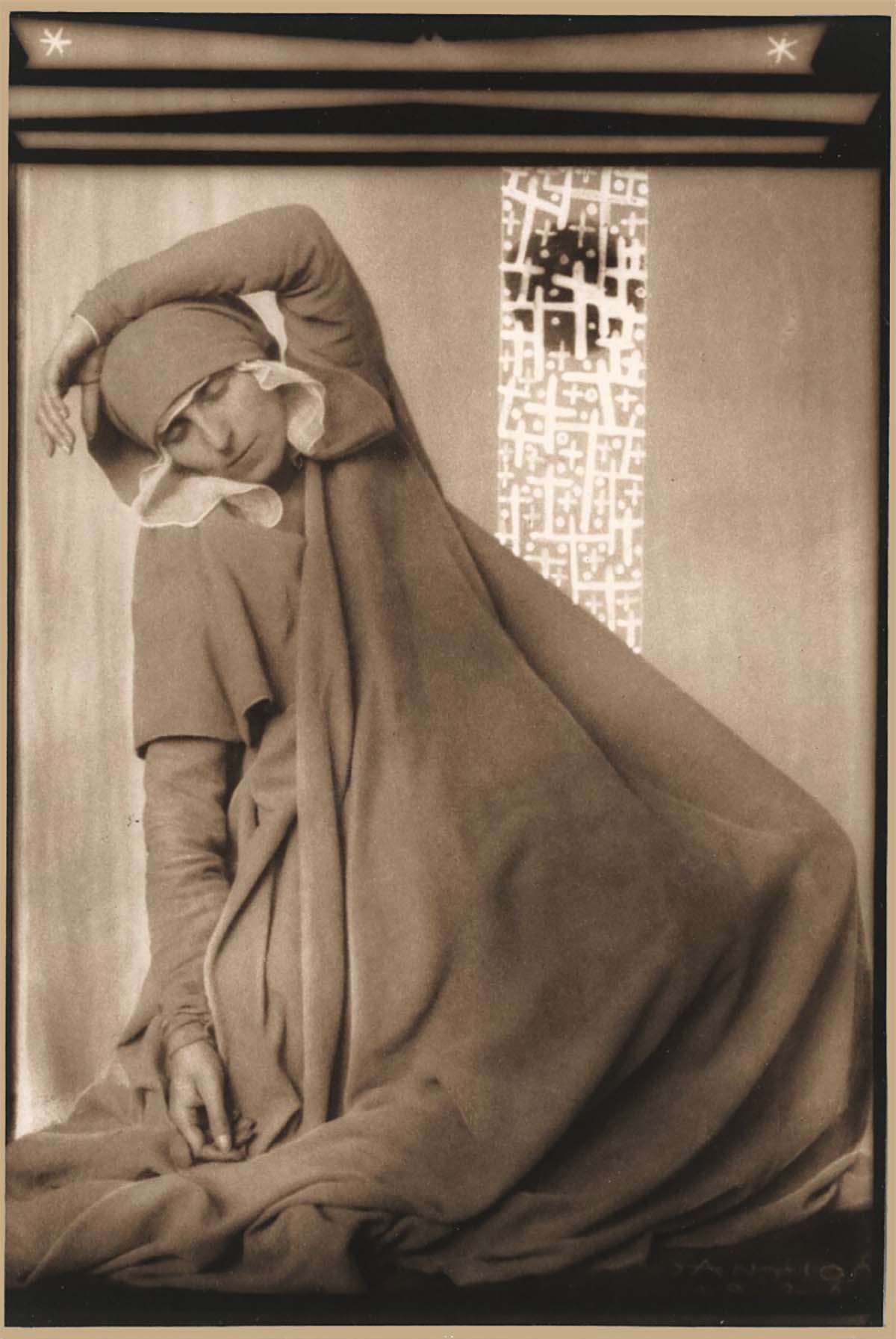

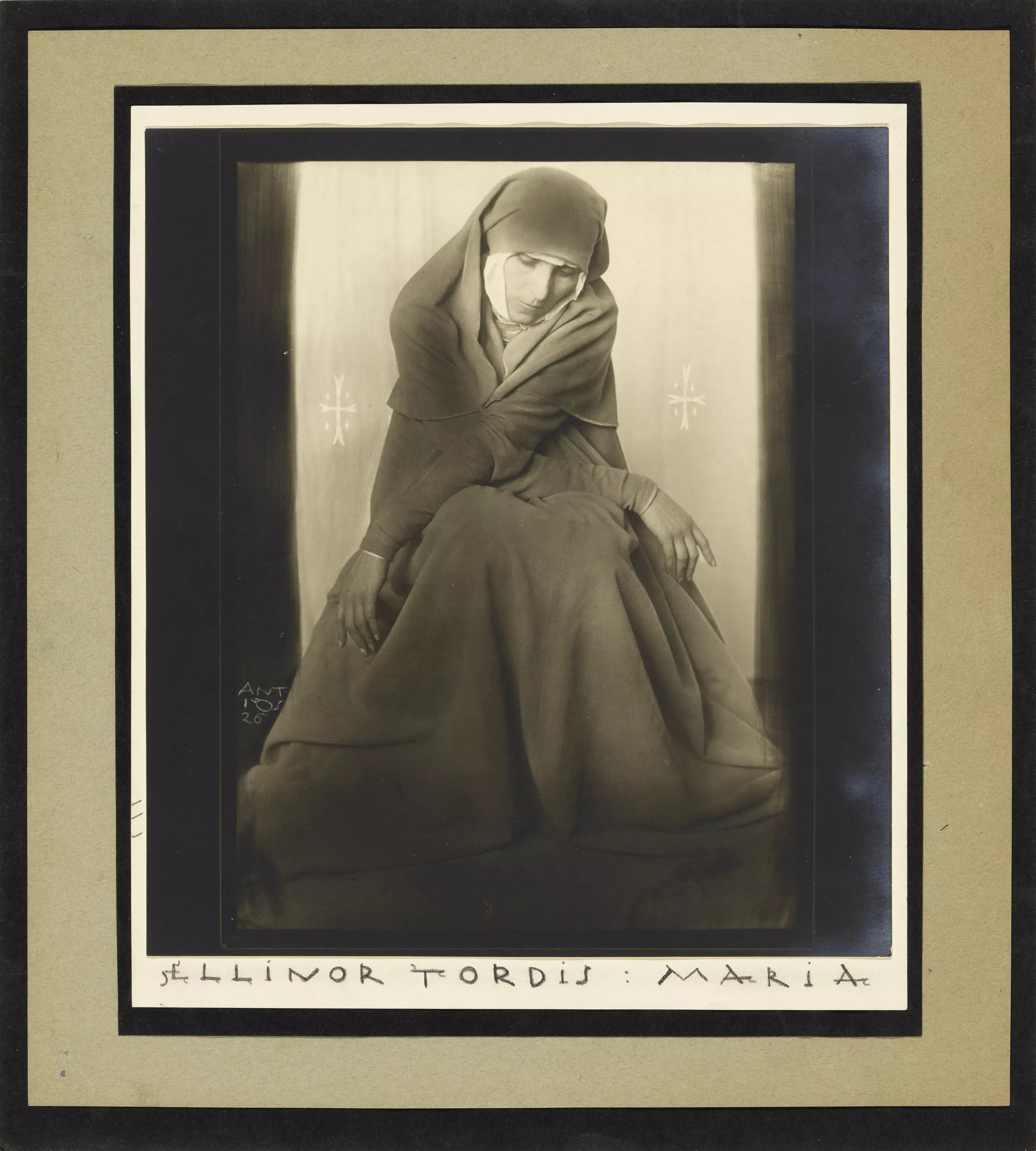

ANTIOS – this clearly legible and decorative signet is as much an effective design element of his famous portraits as EGON SCHIELE’s signature. For a long time, it seemed no one was interested in the fact that this legendary Viennese painter and self-portraitist could not have produced such accomplished photographs without the cooperation of a partner who was a master of photographic technique. The way expressive movement blends with the demands of ”classic” portraiture, or the way graphic outline contrasts with the two-dimensional rendering of figures and garments – this cannot have been the work of an amateur.

An amateur he certainly was not, this Anton Josef Trčka, who contracted his own name to form the artistic trademark ANT(on) IOS(ef) during his third year of studies at the “Graphischen Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt” (Institute of Graphic Instruction and Experimentation) in Vienna. This specialized learning institute for photography and reproduction technology, the first of its kind worldwide, was founded in 1888 in the tradition of the commercial arts schools, and combined the demand for technical perfection with solid instruction of an artistic nature. The young Trčka found in Karel Novak (later the co-founder of a similar school in Prague that produced the likes of Sudek or Rössler) a teacher, who not only taught his students how to turn the idea of Pictorialism into professional practice, but also conveyed an understanding of classical portraiture and a love of contemporary painting. The level of Novak’s influence can be seen in the way artists such as Rudolf Koppitz or Trude Fleischmann, along with ANTIOS, remained true their life long to decorative design devices particular to their teacher.

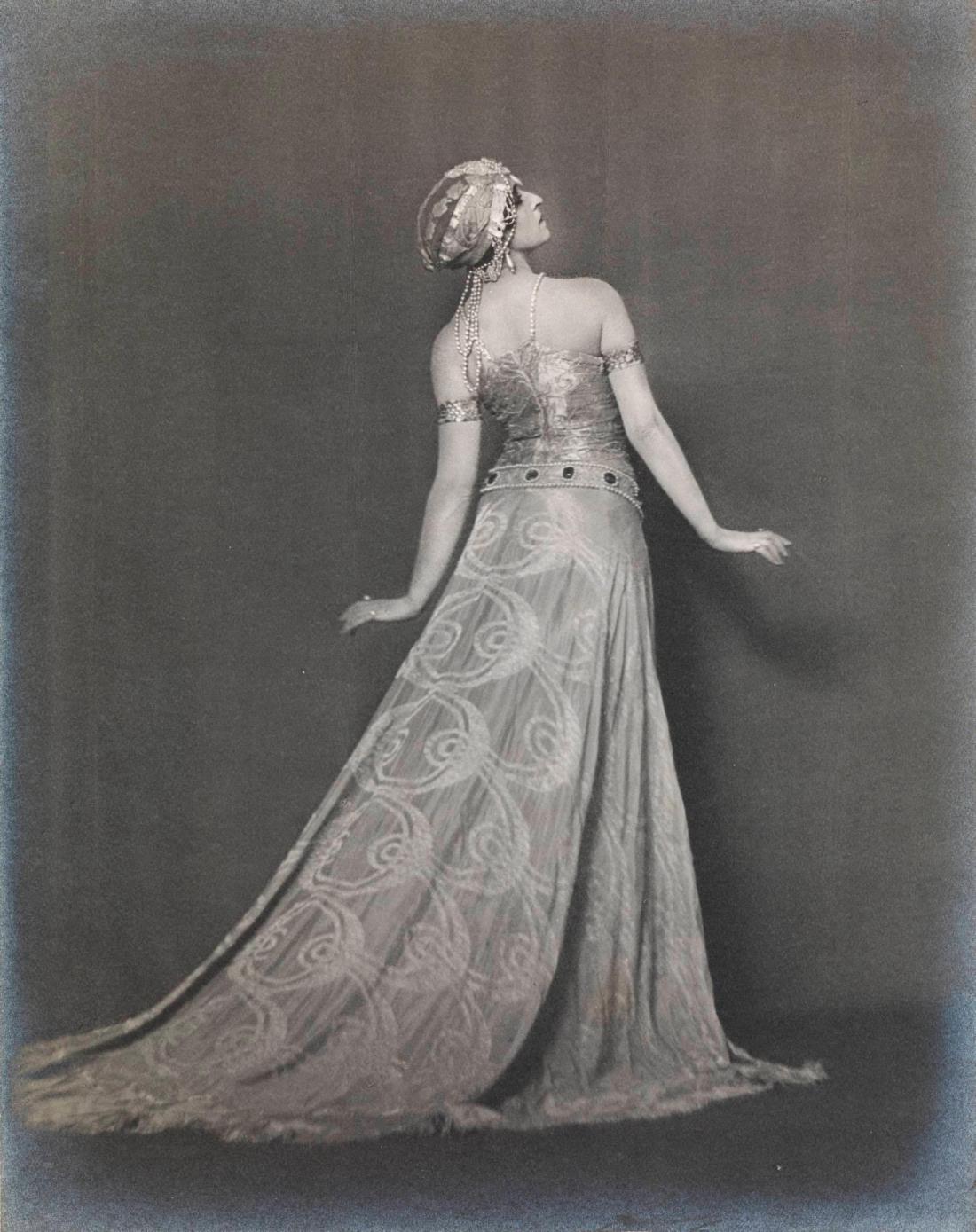

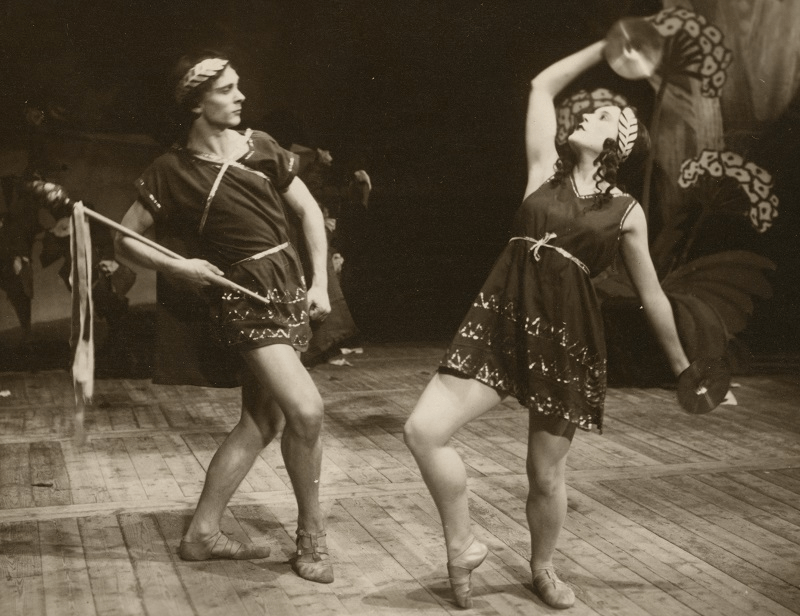

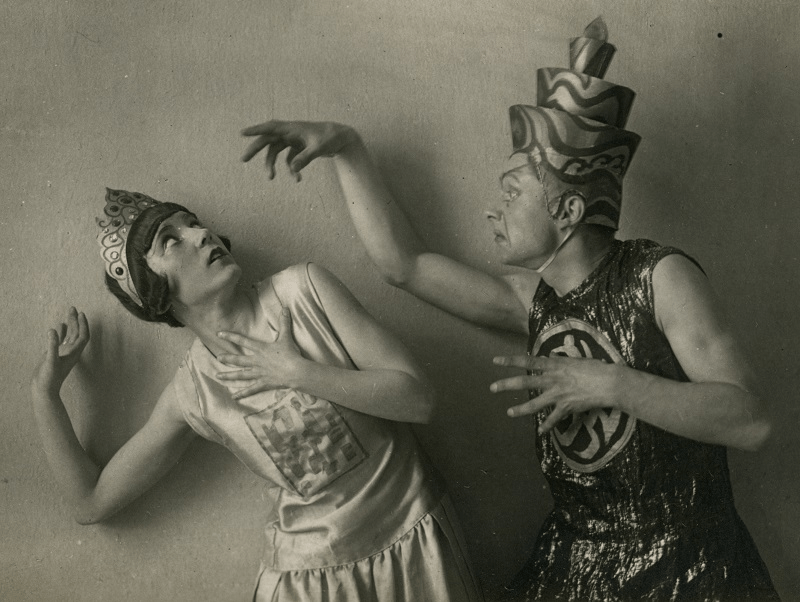

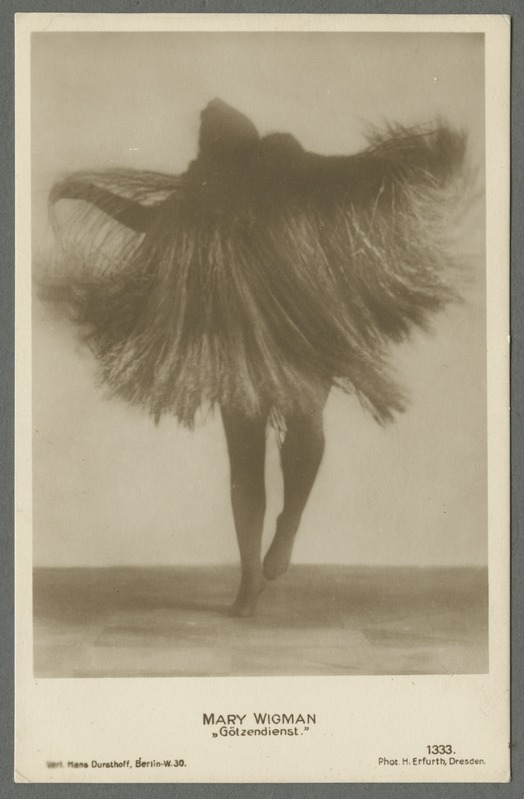

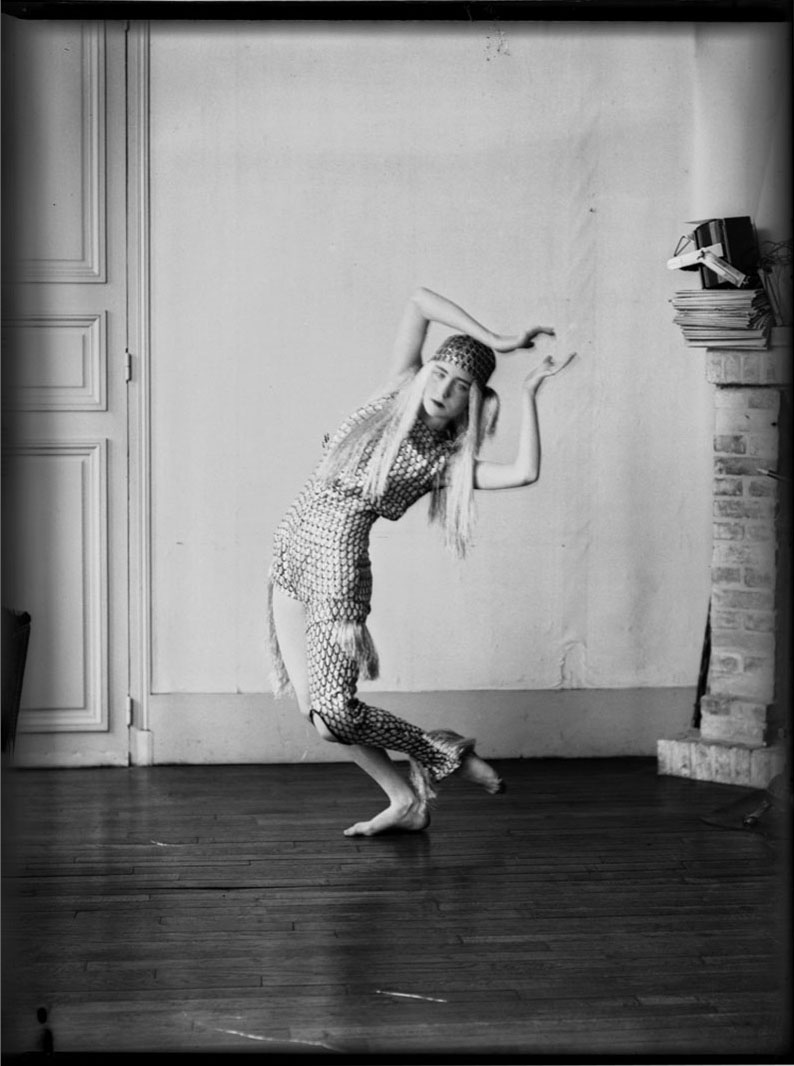

Well before his Schiele and Klimt portraits, ANTIOS had experimented with compositions that were indebted to Jugendstil. The dynamic contours of his figures appear to be inspired by the work of those young dancers who, in the first decades of the 20th century, consciously distanced themselves from classical ballet. By 1924, Trčka had developed close friendships with several dancers, including Hilde Holger and Gertrud Bodenwieser, and these found expression in photographic dance studies, nudes and portraits, and even drawings and poems. During this period, he developed a portrait style that clearly sets him apart from what is generally considered to be the international avant-garde of the 1920’s, yet at the same time is far removed from the great amateur art photographers at the turn of the century. ANTIOS’s imagery – with its wonderfully circular compositions, the painterly reworking by the artist himself, and the integration of the image title and his signature – radiates a deeper melancholy stemming from a determination for perfection that stands diametrically opposed to the photographic goals of the ”Neues Sehen” movement.

As early as his student years, the young Trčka considered himself not only a photographer but also – or mainly! –a painter and poet. And he put these inclinations to use in the service of his intense interest in religion, theosophy and anthroposophy. His admiration for Rudolf Steiner was second only to his admiration for Otokar Brezina, a Czech Poet who at the turn of the last century, created a language based on religion and nature that turned against traditional poetry as well as the hated Austrian domination. Due to this conflict between his Czech roots and the Austrian identity forced (due to economic reasons) on him, and driven with missionary zeal for Anthroposophy, Anton Josef Trcka would be damned to a lifelong existence on the margins. He saw his photographs and paintings exhibited only once in his lifetime, his poetry was made public only through private readings. However, his few friends and admirers, such as Hilde Holger, found in his work something extraordinary that accompanied them in times of escape or emigration. (Text by Monika Faber) ~ quoted from Galerie Kicken Berlin