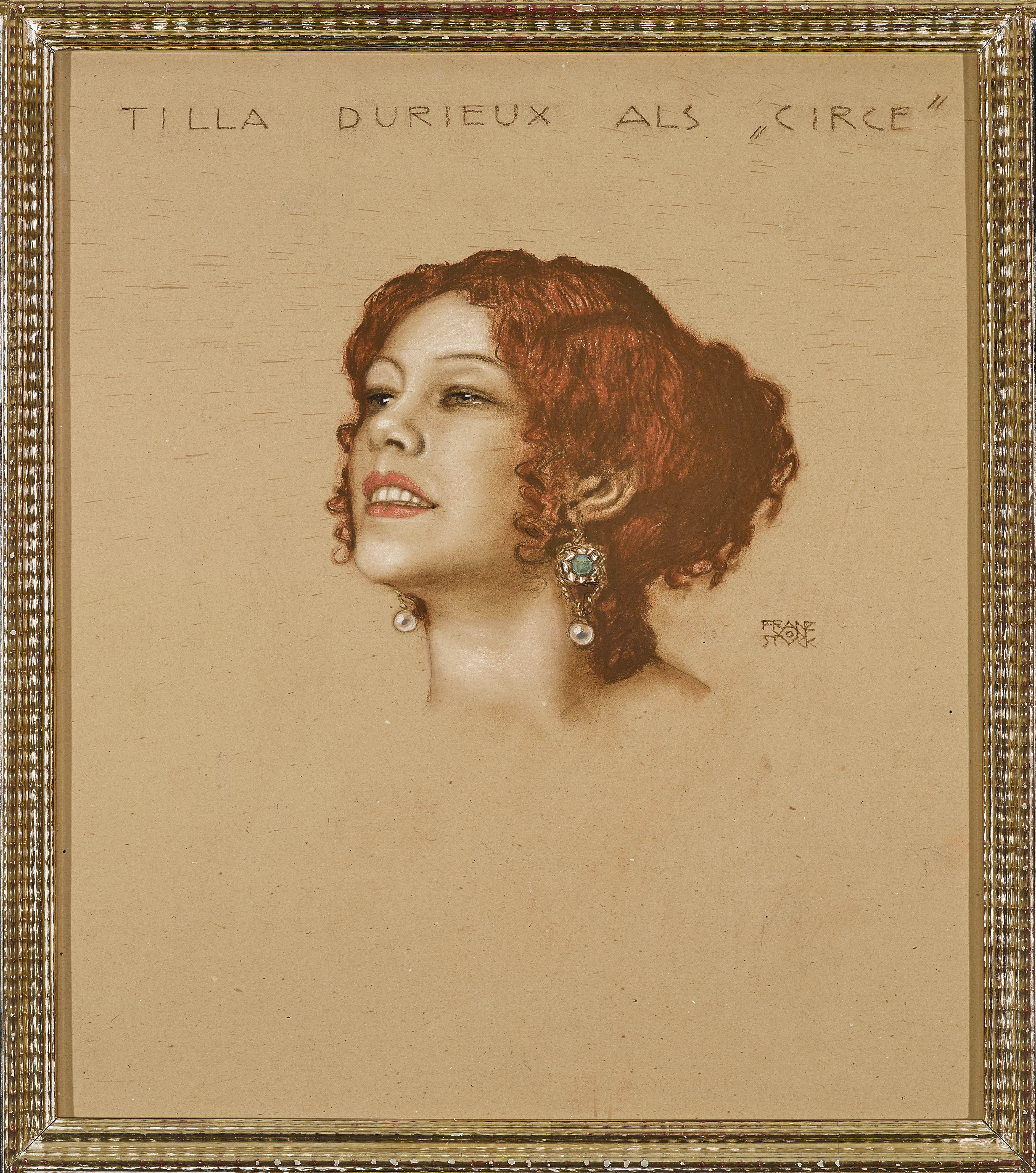

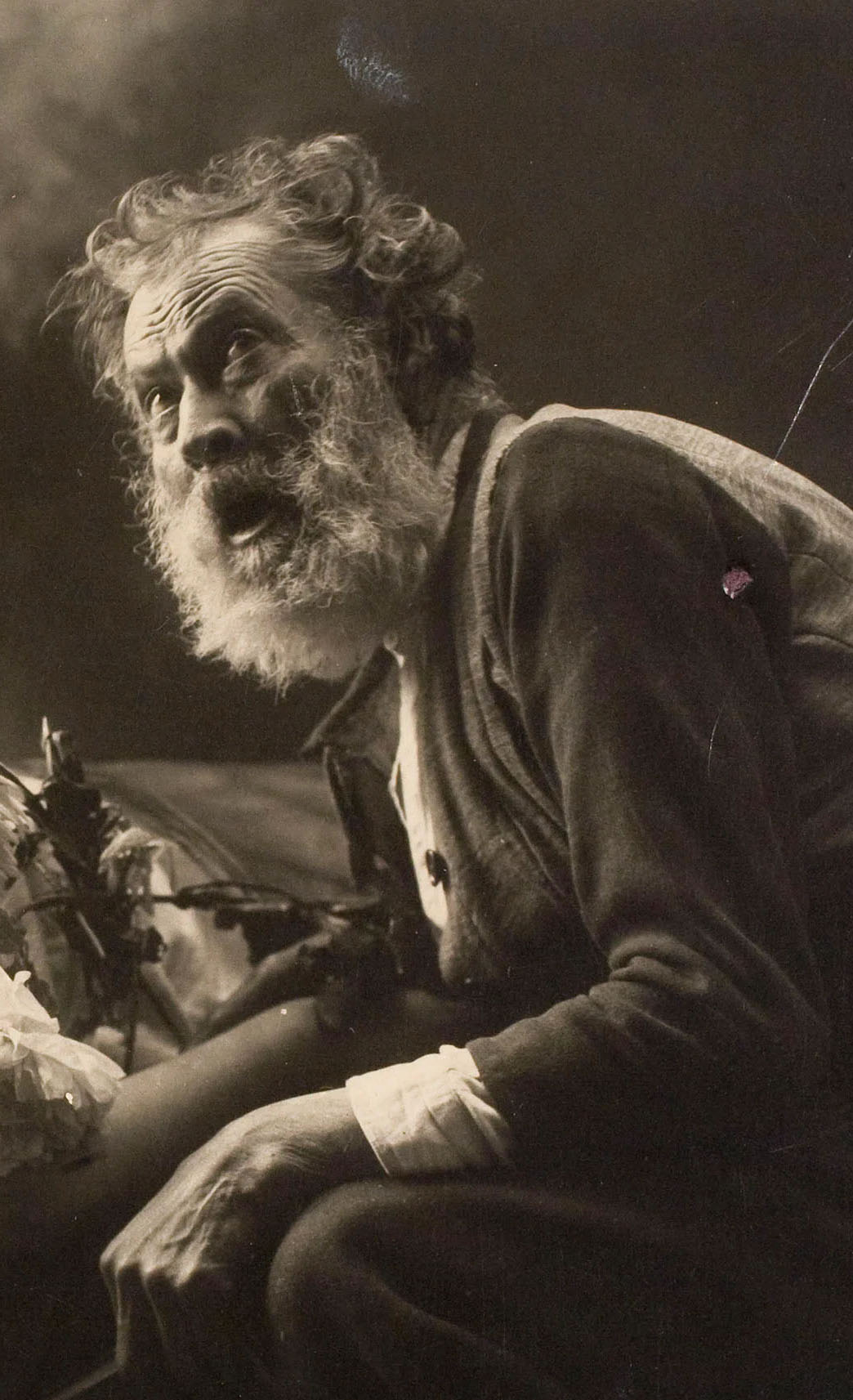

Eitelkeit | Vanity, 1914

images that haunt us

Salome’s studio photographs carry a charge of tense poses, movement and dynamic play with light. The role of Salome is played here by his wife Ervína Kupferová. The photo shows Drtikol’s interest in Art Nouveau, symbolism, historical and mythical themes. (quoted from source Arthouse Hejtmánek)

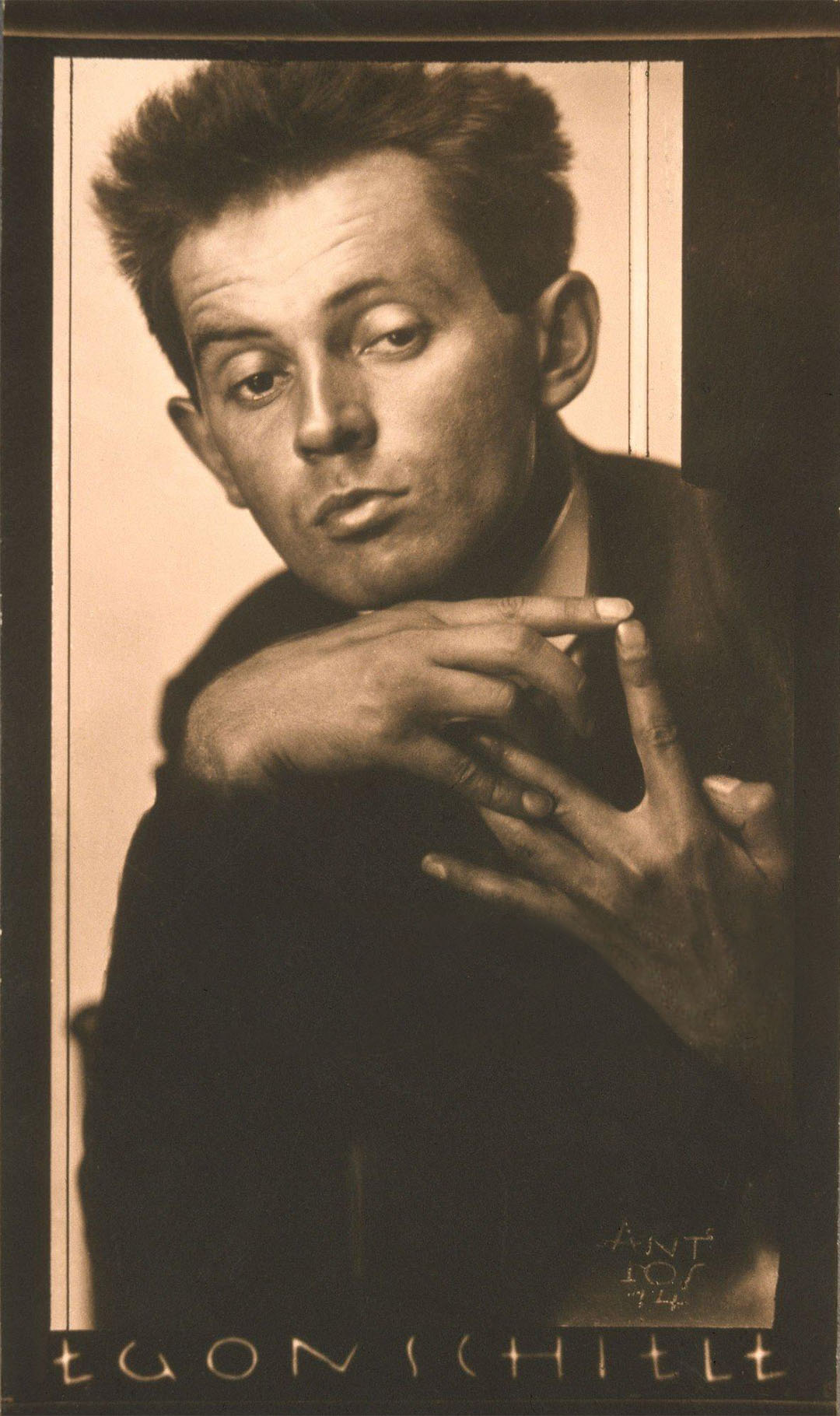

“Antios” in strangely winding letters can be found repeatedly on portraits of Egon Schiele. The portraitist behind this pseudonym, Anton Josef Trcka, was born in Vienna in 1893. Not only is he forgotten, today, he hardly even existed in the consciousness of the contemporary art scene of his time.

He was so little the conformist as a poet, painter and photographer that he never belonged to any group and almost never found an opportunity for exhibition or publication. And yet within a small circle of painters, dancers and writers he was considered a brilliant portraitist. Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt and many others held his paintings in high regard and recommended them to friends, who preserved them during their emigration. Prints of his drawings and copies of his poems were passed along. After Trcka’s death in 1940, his atelier was a refuge for the ostracised spiritual movement of anthroposophy in Vienna. In 1944 a bomb there destroyed almost his entire life’s work.

The widely scattered items that survived have now been brought together for the first time. The artistic works created between 1912 and 1930 allow us to reconstruct the personality of this artist, who throughout his life wavered between the influence of art in Vienna and that of the Bohemian homeland of his family. The expressive language of Egon Schiele can be found in Trcka’s photography side by side with Symbolist echoes and motifs from Czech folklore.

The photographer, painter and poet Anton Josef Trcka was born in Vienna on September 7, 1893. His parents came from Moravia and brought up their three children to be conscious of their Czech nationality. Trcka’s life and work were marked by an inner conflict between his inclination to Slavic influence and the fact of his life in Vienna with the influence of the artists there. He was, for example, a friend of both the nationalist Czech poet J. S. Machar and the eccentric Viennese poet Peter Altenberg. In 1911 he entered the Royal and Imperial School of Graphic Arts, where Karel Novak became his teacher. Trcka experimented with new photographic techniques. Some of his pictures were produced both in silver bromide and bromoil prints, and thus as mirror images. Often the background of the negative was altered with a brush in order to realise the young artist’s visual ideas, which had been influenced by Symbolism and the Pre-Raphaelites.

At the beginning of 1914 the artist met Egon Schiele, who performed the expressive gestures and poses of his self-portraits before the camera. Apparently the photographer had previously prepared reproductions of paintings for the artist, who was only a few years his senior.

The gestural language of Schiele, which was related to “New Dance” and likely also to French scientific documentation of the body language of hysterical women, contradicts everything that was typical in portraits up to that time. Trcka was already signing his works with “Antios” (a combination of his two first names). With his style related to the “classical” portrait of the 16th century with its frontal structure and the integration of writing he was able to create an ideal framework for the unusually expressive postures of the painter. Just as Schiele’s portrait style was to influence Trcka’s photographic human portraits in the coming years, the young photographer’s landscapes and his early watercolours show his admiration for Gustav Klimt and the two-dimensional ornamental structure of his paintings. At the same time Trcka concerned himself with Czech folklore, for example, with the kind of floral ornaments familiar from old embroidery. From this he developed a highly individual, almost abstract watercolour style.

The direct or indirect contact with Czech artists of the so-called “Prague Modern” movement also drew Trcka’s attention to the religious motifs typical of his great role models, the poet Otakar Brezina and the sculptor Frantisek Bilek.

In 1915 Trcka met the poet Anna Pamrova, who introduced him to Brezina. Their idealistic-ascetic image of artistry had as great an influence on the young man as did Rudolf Steiner and his anthroposophical society, which Trcka was drawn to by his future wife, Clara Schlesinger. (text: Monika Faber) quoted from Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

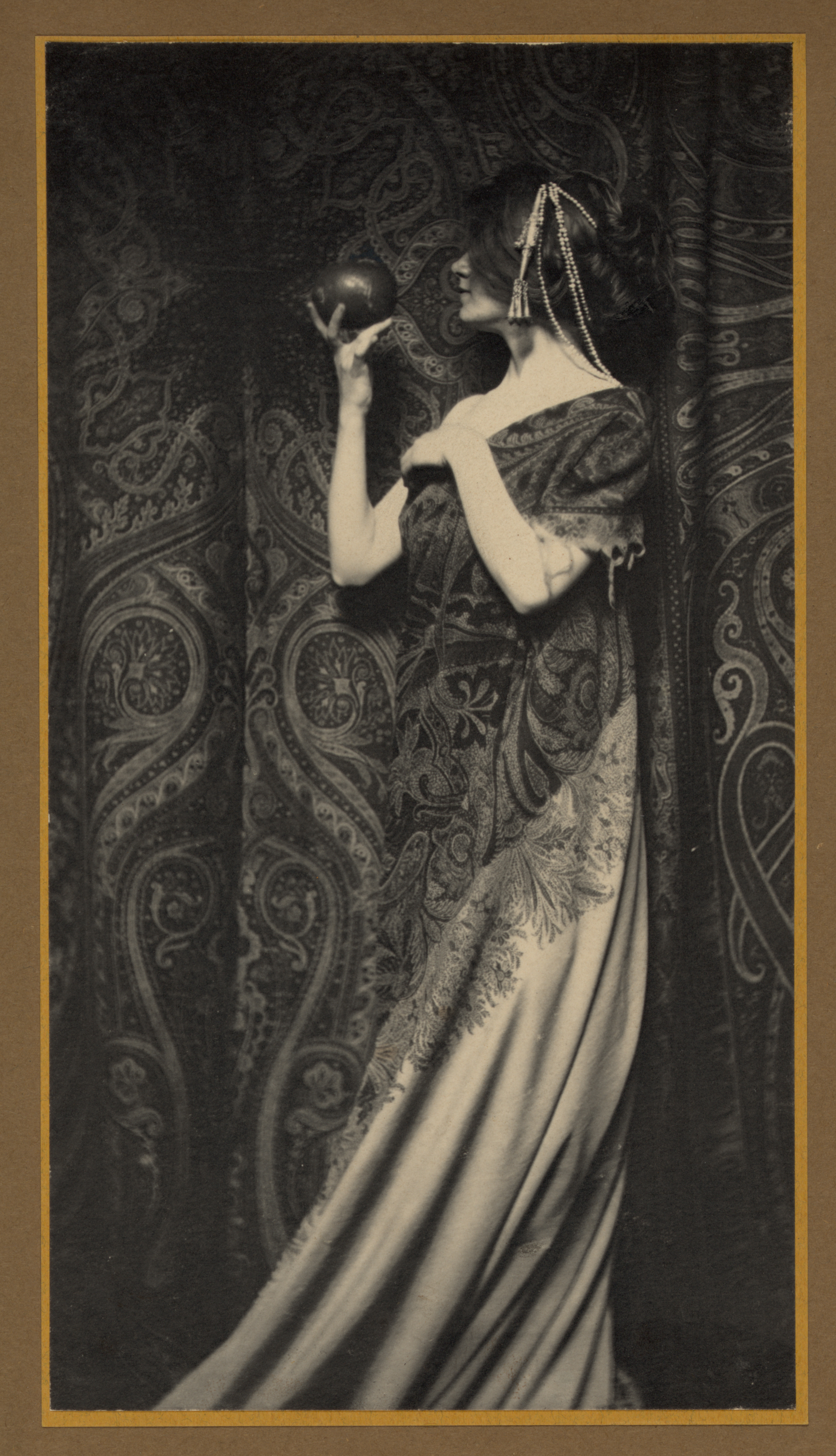

The Odor of Pomegranates is more than simply a portrait, the image represents Ben-Yusuf’s effort to use photography to explore a larger theme: in this case, the seductiveness and potential danger of something desirous.

Ben-Yusuf’s artistic explorations within the tradition of portraiture continued alongside her commercial work. One of the prints she felt was more successful was The Odor, a work that she exhibited on at least half a dozen occasions in the years immediately after its completion in 1899. No other photograph by her was displayed or reproduced as often. This portrait shows an unidentified young woman holding a pomegranate only inches before her face. The subject is dressed in an ornately decorated garment and stands erect in profile against a similarly patterned fabric that serves as the backdrop for the photograph. A string of pearls is interwoven in her hair. As the photographer and critic Joseph Keiley observed in his review of this “especially striking” image, “the figure was posed against a darker piece of heavy oriental drapery, figured with curved lines that resembled writhing serpents, and into which the draped figure almost melted.” Others, including the photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn, also commented on Ben-Yusuf’s effort to meld the her subject into the folds of the backdrop. The effect of this compositional strategy is a radical flattening of the picture plane so that the figure appears like a mythological personage carved on to a frieze. Capturing likeness is not the goal of the composition; instead, Ben-Yusuf is more concerned with the larger creative possibilities of photography. (…)

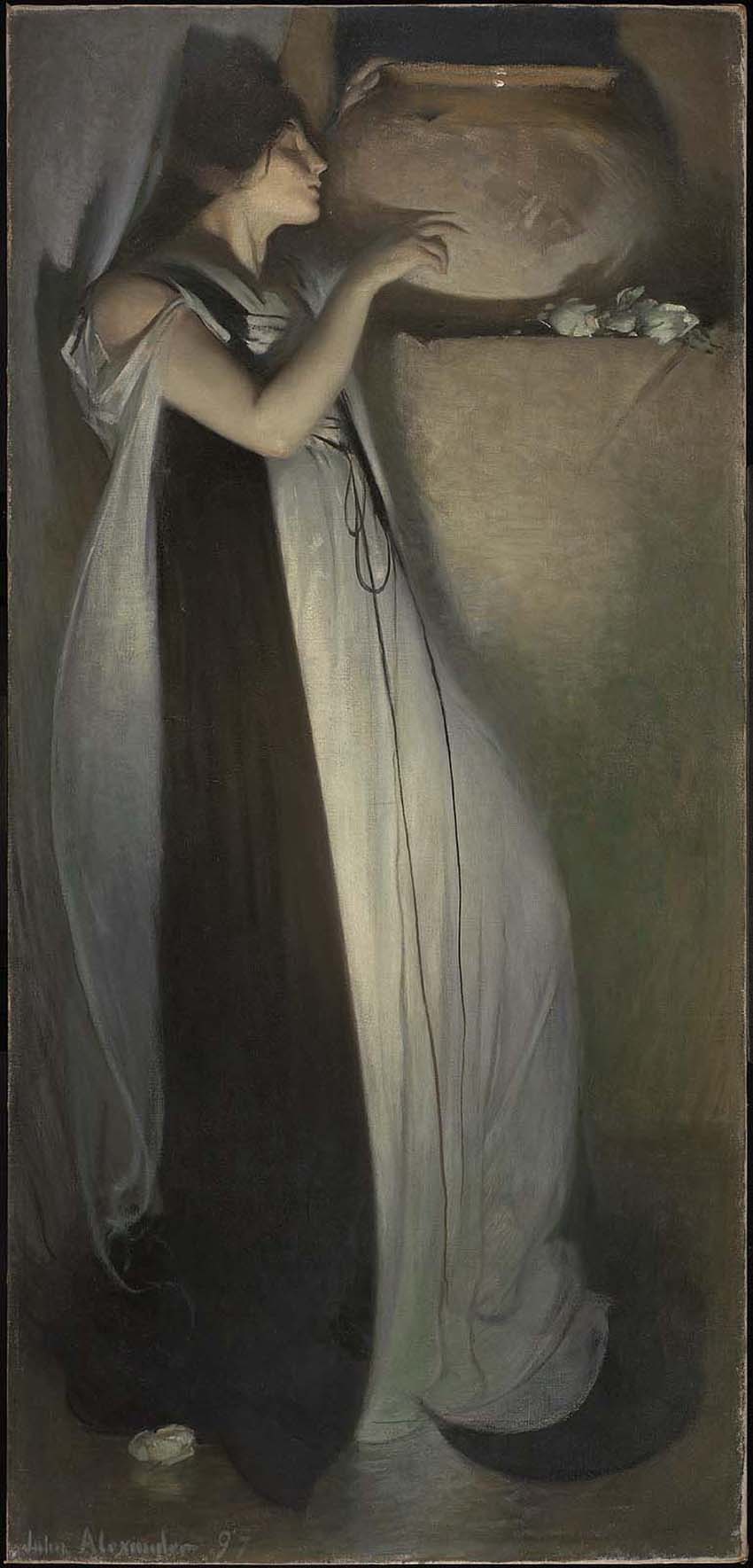

Ben-Yusuf was closely allied with those [photographers] who saw photography as a medium of artistic expression. To her and other like-minded practitioners, much could be learned from the world of the fine arts and literature, and this new class of photographers went to great lengths to create prints that incorporated this lessons. As the scholar Naomi Rosenblum has shown, The Odor of Pomegranates owes much stylistically to such works as John White Alexander’s painting, Isabella and the Pot of Basil [image below]. Ben-Yusuf admired Alexander, and two years later completed a series of portraits of the artist. In its subject matter, its composition, and its presentation, Ben-Yusuf’s image reveals the influence of the late nineteenth-century avant-garde. (…)

In The Odor of Pomegranates, Ben-Yusuf herself experiments with creating a photographic portrait that is as much about Classical mythology as it is about modern life. The pomegranate that the woman holds before her provides a key to unlocking the work’s larger symbolism. An odorless fruit, the pomegranate has long been a popular subject for artists and poets, many of whom have seen it as a symbol of the Resurrection. In Greek mythology, it figures prominently in the story of Persephone, the beautiful daughter of Zeus and Demeter, whose eating of a pomegranate given to her by Hades bound her for part of the year in the underworld over which he reigned. During those months, Demeter -the goddess of harvest- refused to allow anything to grow, and thus winter began. Ben-Yusuf depicts her Persephone-like figure observing closely -even contemplating- the fruit before her. Its “odor” relates not to its smell, but rather the tantalizing expectation that precedes the act of consuming the pomegranate.

Ben-Yusuf’s The Odor of Pomegranates is a departure from the professional photography that typically occupied her. Not concerned with capturing a sitter’s individuality, she explores in this portrait a more universal theme: the seductiveness and potential danger of something desirable. (…)

Although the long hair of Ben-Yusuf’s subject hides her eyes, it appears that this woman stares out at the pomegranate she holds as if pondering whether to act. Her other arm rises upward in a gesture that suggests a certain hesitation. The Odor of Pomegranates captures the tense moment of decision.

Quoted from: Goodyear, Frank H., III: Zaida Ben-Yusuf : New York portrait photographer. London : Merrell (2008) Published in association with the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. The book is available at internet archive

Isabella, or The Pot of Basil was a poem written in 1820 by the English poet John Keats, who borrowed his narrative from the Italian Renaissance poet Giovanni Boccaccio. Isabella was a Florentine merchant’s beautiful daughter whose ambitious brothers disapproved of her romance with the handsome but humbly born Lorenzo, their father’s business manager. The brothers murdered Lorenzo and told their sister that he had traveled abroad. The distraught Isabella began to decline, wasting away from grief and sadness. She saw the crime in a dream and then went to find her lover’s body in the forest. Taking Lorenzo’s head, she bathed it with her tears and finally hid it in a pot in which she planted sweet basil, a plant associated with lovers.

Alexander used theatrical effects to render this grim scene, isolating Isabella in a shallow niche and lighting her from below, as if she were an actor on a stage illuminated only with footlights. This eerie light, the cold monochromatic palette, and the sensuous curves of Isabella’s gown all draw the viewer’s eye to the loving attention Isabella gives the pot, which she gently caresses. Isabella seems lost in an erotic spectral trance, oblivious to the world and to observers. With his strange subject, Alexander created an extraordinary and mysterious image of love gone awry.

quoted from MFA and the text was adapted from Elliot Bostwick Davis et al., American Painting

The massive industrialization of the photography based on the new models of Kodak in 1888, marked the birth of amateurism, and what could be considered its elitist complement and counterpart, Pictorialism, understood to be the first discourse of artistic legitimization of photography.

Faced with technological standardization and documental utilitarianism, Pictorialism proposed the use of pigmentary techniques that evoked the manual work of paintings, as well as their symbolic, picturesque or sublime themes, in accordance with the aesthetic paradigms of the modern art of the 19th century, which was based on the romantic principle of genius. In some way the concept of “creation” was introduced into photographic techniques, vindicating the figure of the photographer as an author and interpreter of reality. Within this framework, Joan Vilatobà created a series of works which moved between symbolic allegory and customs, and photography through topics such as beauty, death, love, etc., of which Where in heaven will I find you? is an example. | quoted from MNAC ~ Museu Nacional d’ Art de Catalunya

Dancer Laura Devine in a Shadow’s Dance during ‘This Year of Grace’ by Charles B. Cochran, London, 5 October 1928