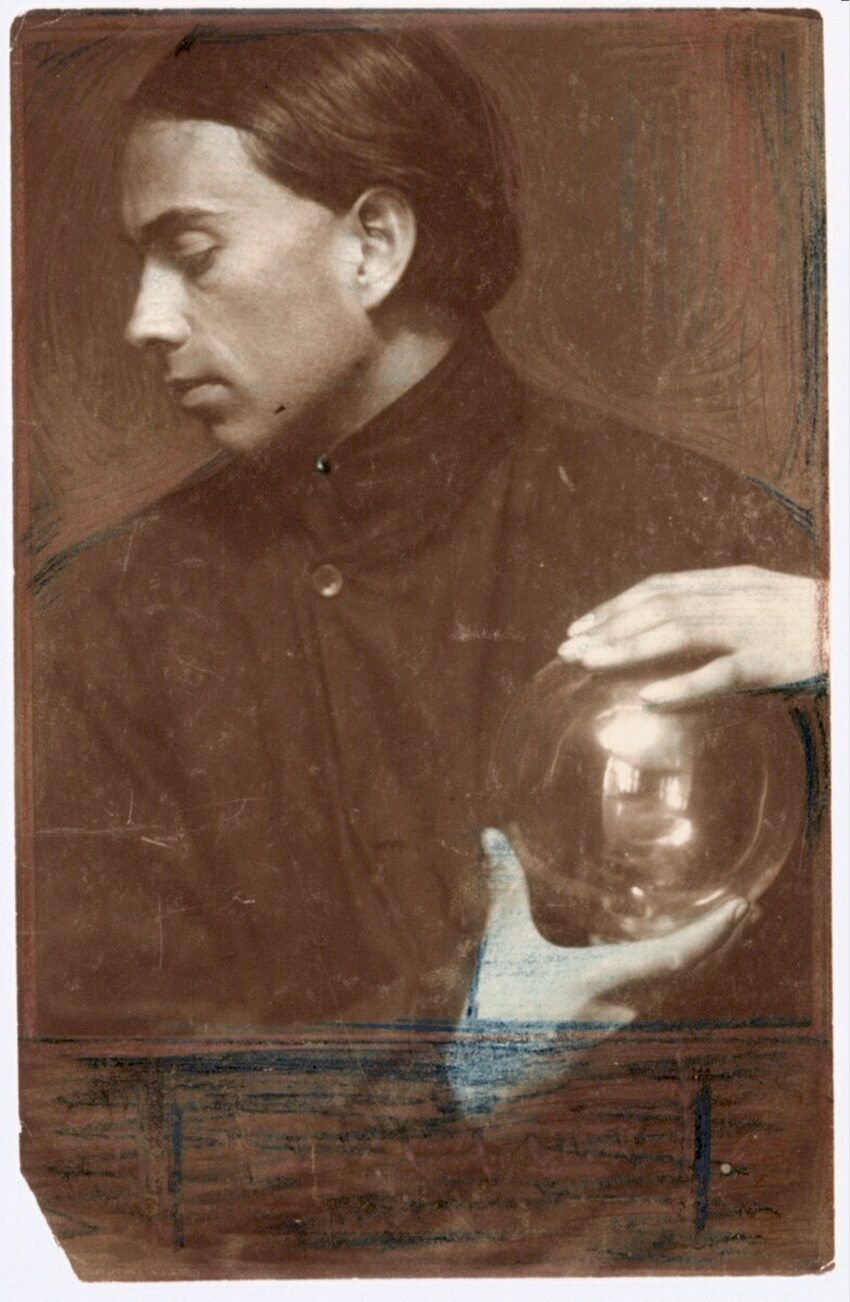

Pictorial portrait by Dumeunier

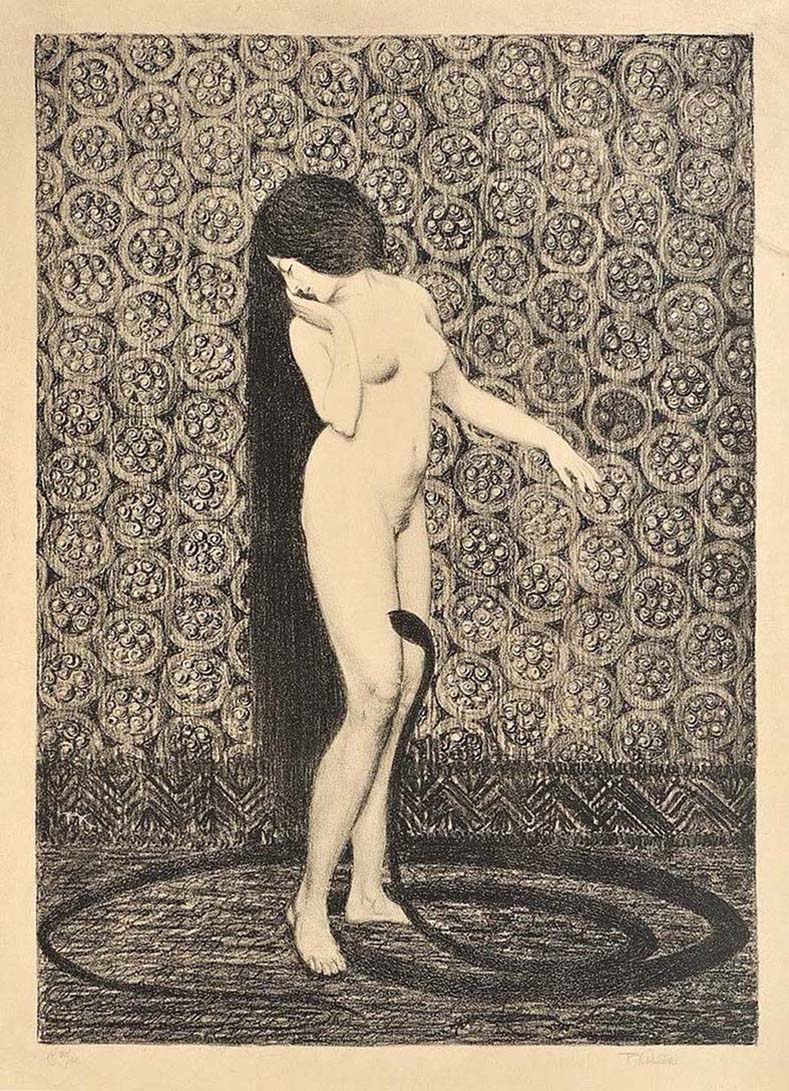

images that haunt us

In the last years of his life, Janis Rozentāls repeatedly returned to the composition with the figures of a princess and monkey. The first of the painting was exhibited in 1913 at the 3rd Baltic Artists Union exhibition and at the international art show in Munich where the Leipzig publisher Velhagen & Klasing acquired reproduction rights ensuring wide popularity for the work. The symbolic content of the decoratively resplendent Art Nouveau composition has been interpreted as an allegory of the relationship between artist and society reflecting the power of money over the artist; on other occasions, the princess is seen as “great, beautiful art” but the monkey as the artist bound by golden chains – its servant and plaything. [quoted from Latvijas Nacionālā bibliotēka (link)]

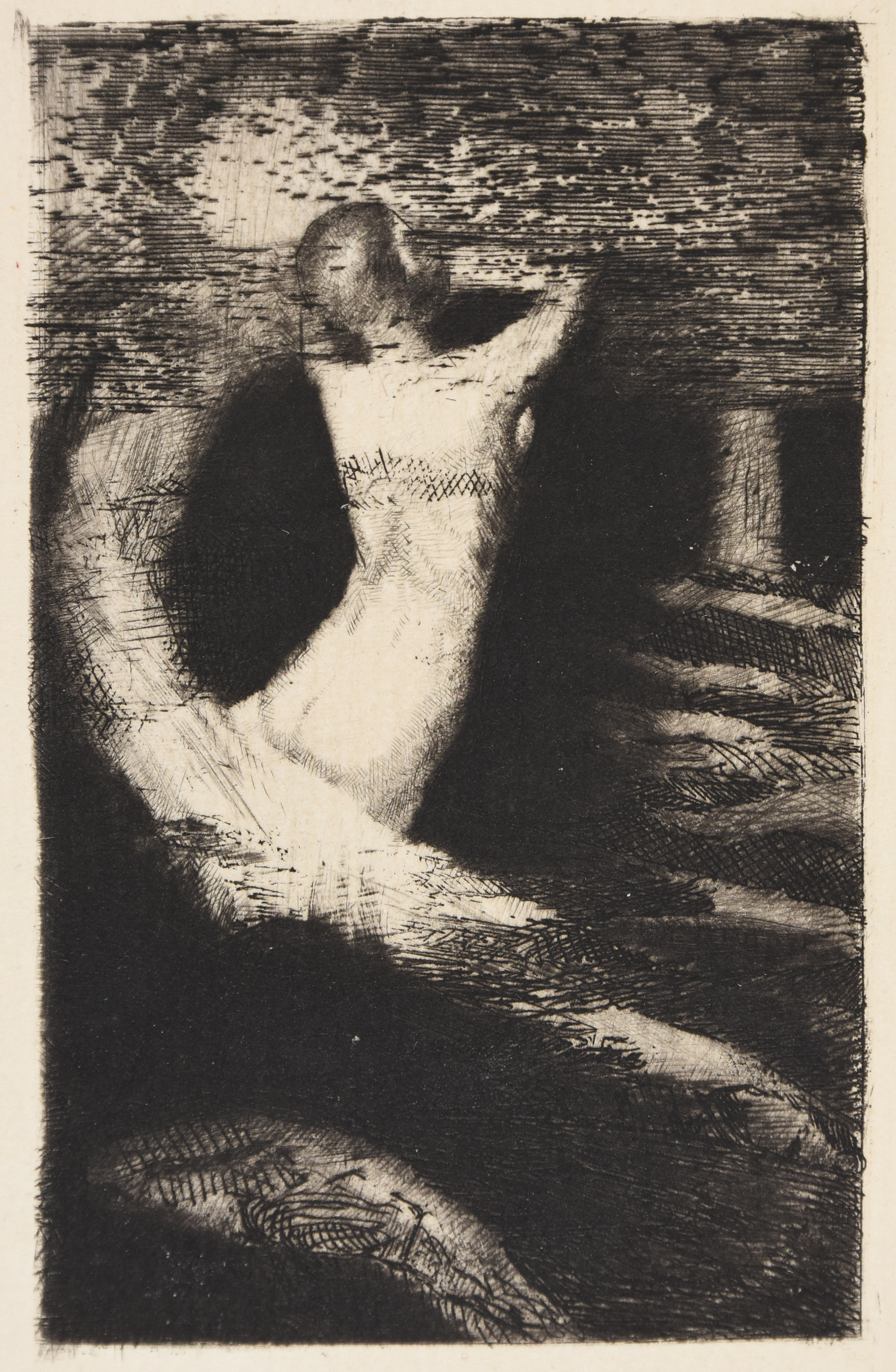

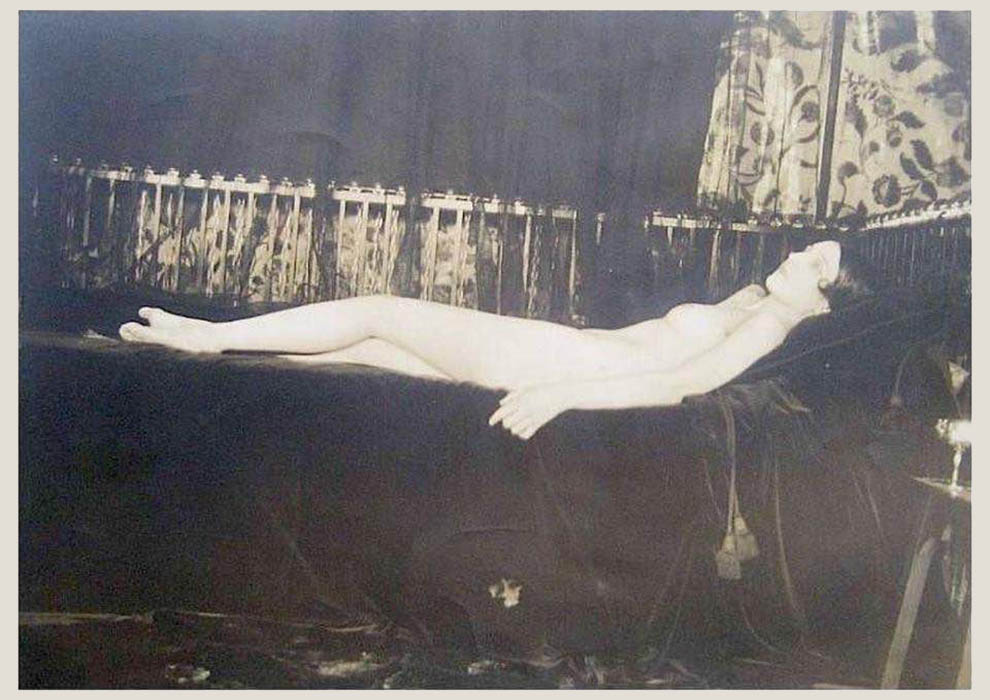

Brooks painted Ida Rubinstein more often than any other subject; for Brooks, Rubinstein’s “fragile and androgynous beauty” represented an aesthetic ideal. The earliest of these paintings are a series of allegorical nudes. In The Crossing (also exhibited as The Dead Woman), Rubinstein appears to be in a coma, stretched out on a white bed or bier against a black void variously interpreted as death or floating in spent sexual satisfaction on Brooks’ symbolic wing. (x)

In 1910, Brooks had her first solo show at the Gallery Durand-Ruel, displaying thirteen paintings, almost all of women or young girls. Among them, Brooks included two nude studies: The Red Jacket, and White Azaleas, a nude study of a woman reclining on a couch. Contemporary reviews compared it to Francisco de Goya’s La maja desnuda and Édouard Manet’s Olympia. But, unlike the women in those paintings, the subject of White Azaleas looks away from the viewer; in the background above her is a series of Japanese prints. (x)

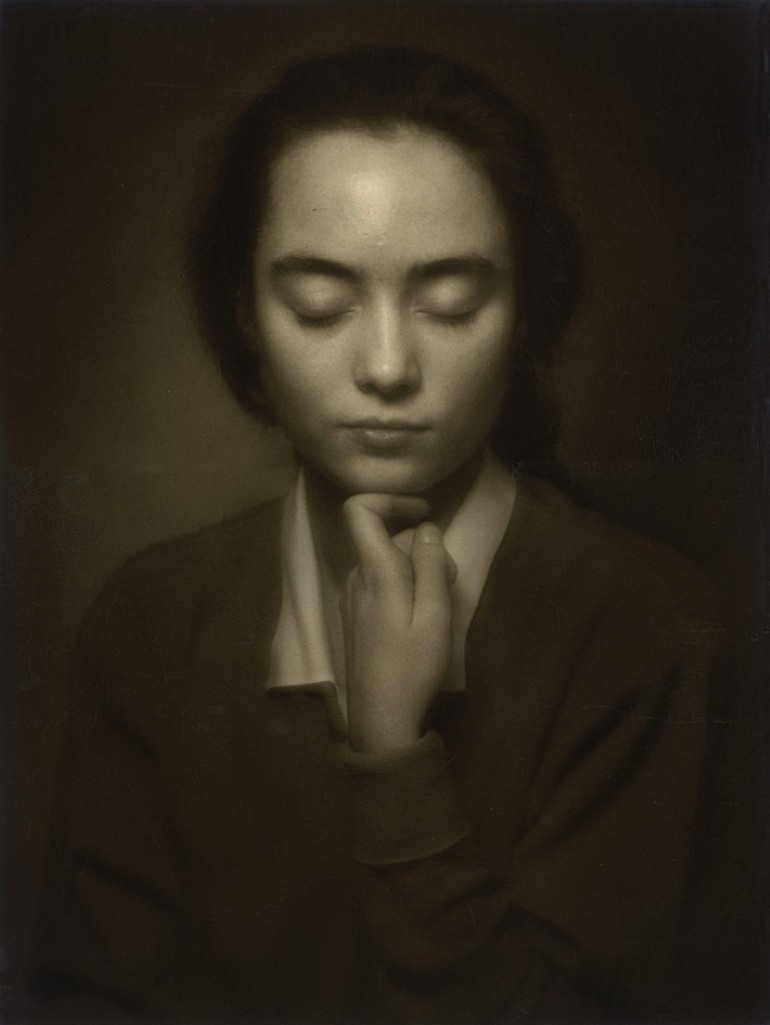

Romaine Brooks remained aloof from all artistic trends, painting, in her palette of black, white, and grays, haunting portraits of the blessed and the troubled, of socialites and intellectuals. She moved in brilliant circles and, while resisting companionship, was the object of violent passions. […] Her story and her work reveal much about bohemian life in the early twentieth century.

Elizabeth Chew Women Artists at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (x)

Describing herself as a lapidée (literally: a victim of stoning, an outsider), at the height of her career Brooks was prominent in the intellectual and cosmopolitan community that moved between Capri, Paris and London in the early 1900s. Brook’s best known images depict androgynous women in desolate landscapes or monochromatic interiors, their protagonists undeterred by our presence, either staring relentlessly at us or gazing nonchalantly past. Her subjects of this time include anonymous models, aristocrats, lovers and friends, all portrayed in her signature ashen palette. Rejecting contemporary artistic trends such as cubism and fauvism, Brooks favoured the symbolist and aesthetic movements of the 19th century, particularly the work of James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Her ability to capture the expression, glance or gaze of her sitters prompted critic Robert de Montesquiou to describe her, in 1912, as ‘the thief of souls’. quoted from Frieze