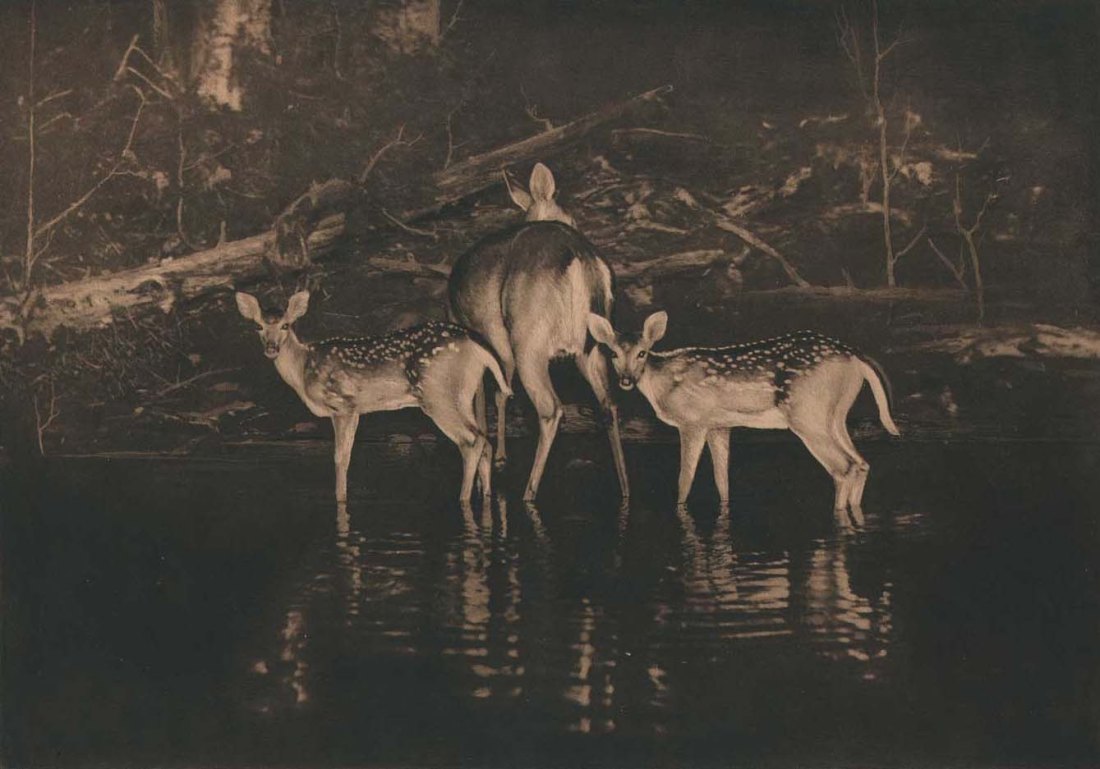

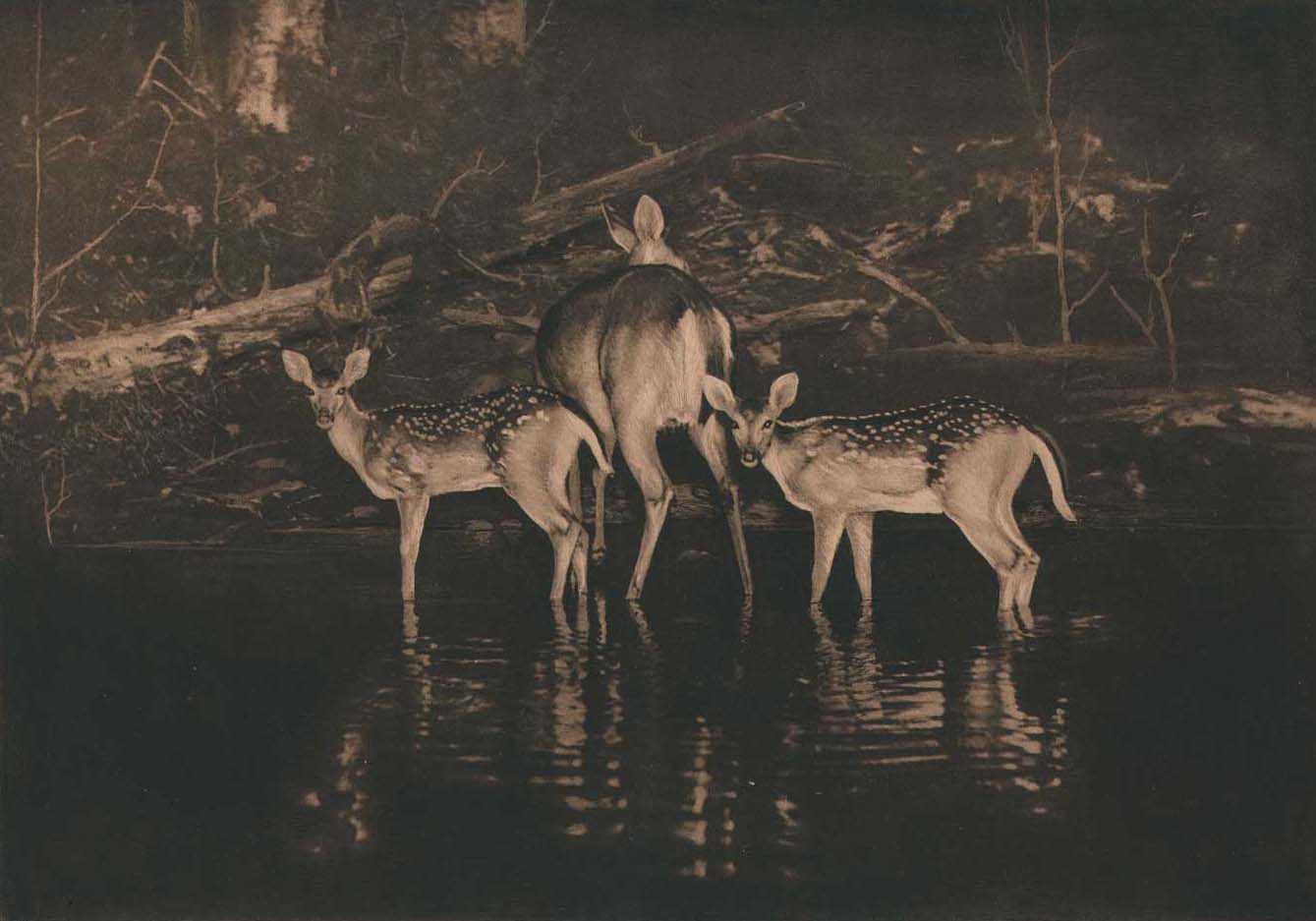

This groundbreaking photograph depicting three deer was taken at night in 1896 on one of the many lakes making up Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. It was eventually issued in 1916 as a large-format hand-pulled photogravure by the National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C. (it had previously appeared several times in the journal as a halftone-one a full-page gatefold). [quoted from PhotoSeed]

A pioneer of using flashlight photography to record wildlife in their natural environments at night, Shiras used the method of “Jacklighting”, a form of hunting using a fixed continuous light source mounted in the bow of a canoe to draw the attention of wildlife: in this case three deer, utilizing magnesium flash-powder to freeze the scene in-camera. His series of twelve midnight views, including A Doe and Twin Fawns -also known as Innocents Abroad, would earn Shiras international acclaim and many important awards.

A one-term Congressman for the state of Michigan, (his father George Shiras Sr. was a former Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court) he was also an important naturalist who helped placed migratory birds and fish under Federal control. (The eventual 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty Act had groundings in legislation Shiras introduced to Congress in 1903 as the first comprehensive migratory bird law not voted on.) For additional background, see article by Matthew Brower in the journal History of Photography, Summer, 2008: George Shiras and the Circulation of Wildlife Photography. [quoted from PhotoSeed]

A doe and her twin fawns feeding on a lake in northern Michigan. From: Hunting wild life with camera and flashlight : a record of sixty-five years’ visits to the woods and waters of North America. Volume I, National Geographic Society, 1935. | src Memorial University of Newfoundland