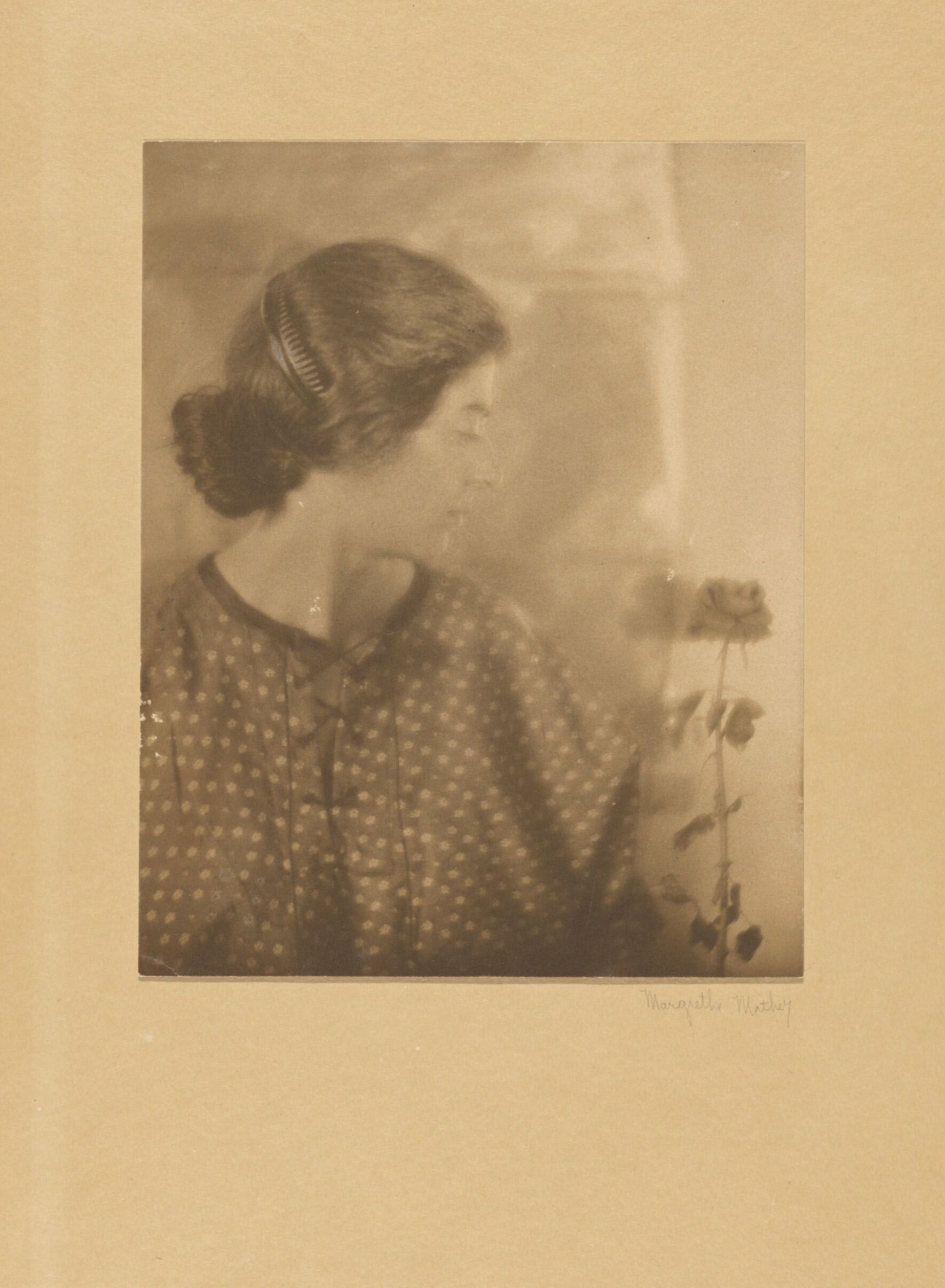

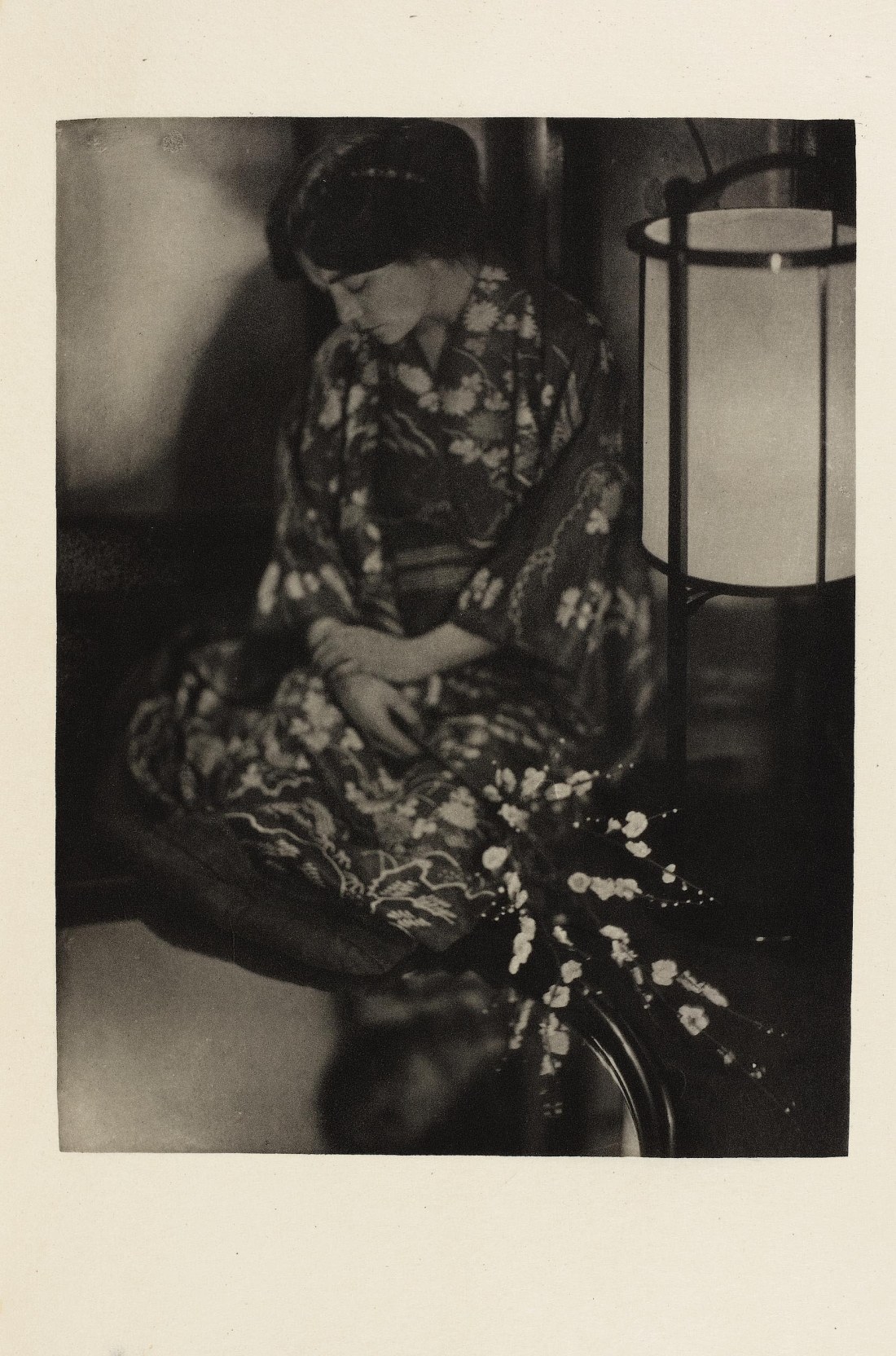

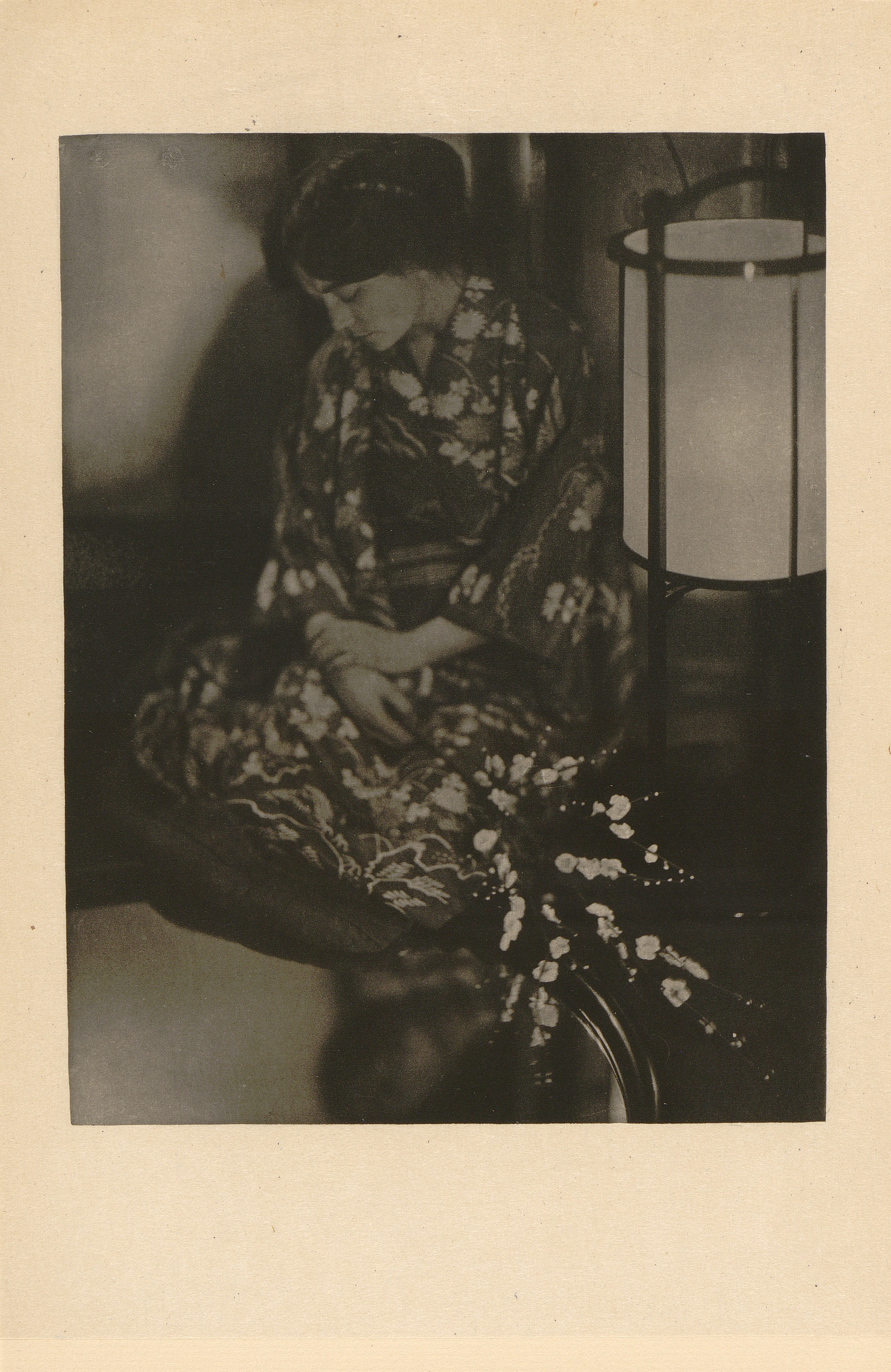

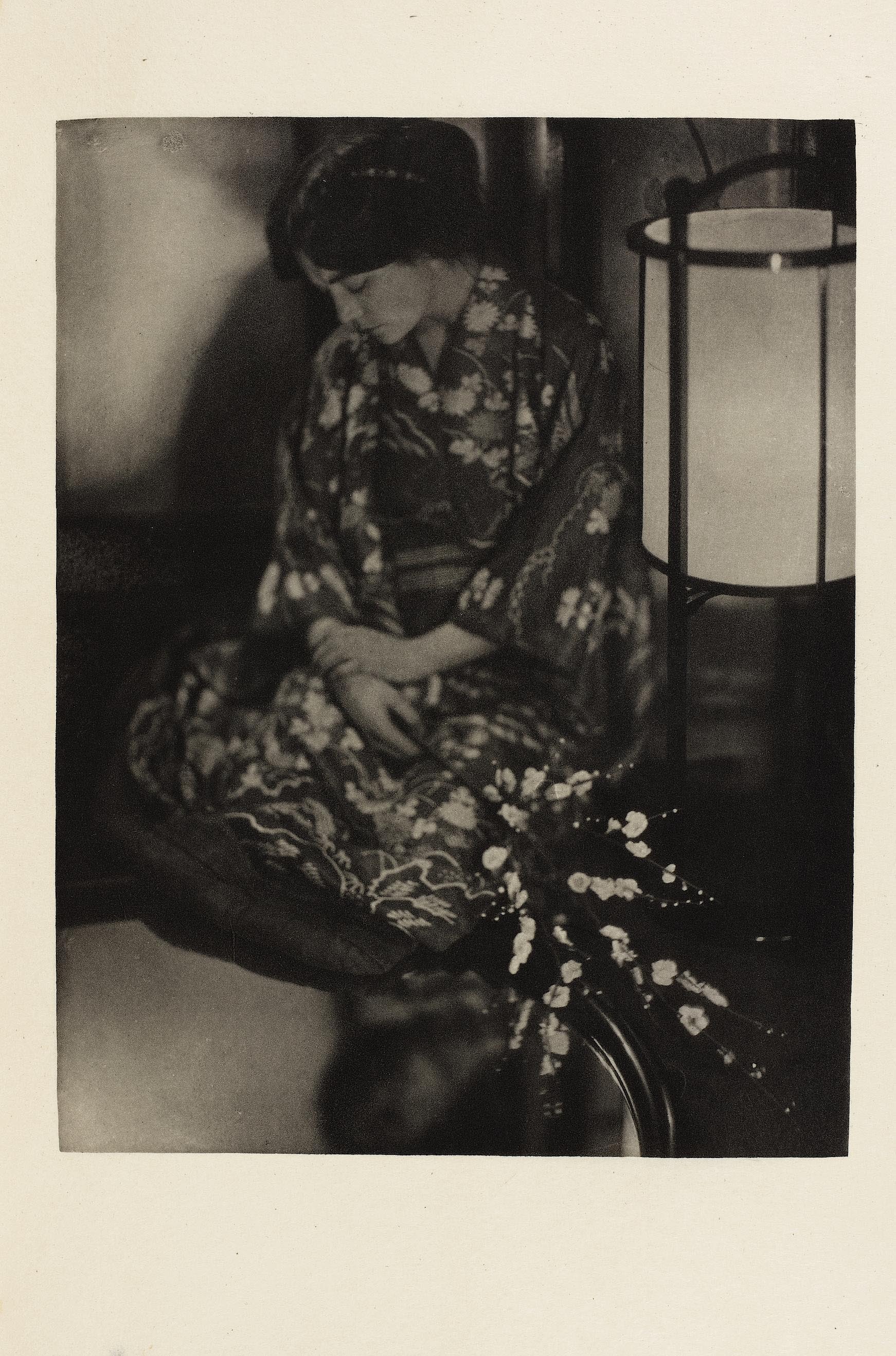

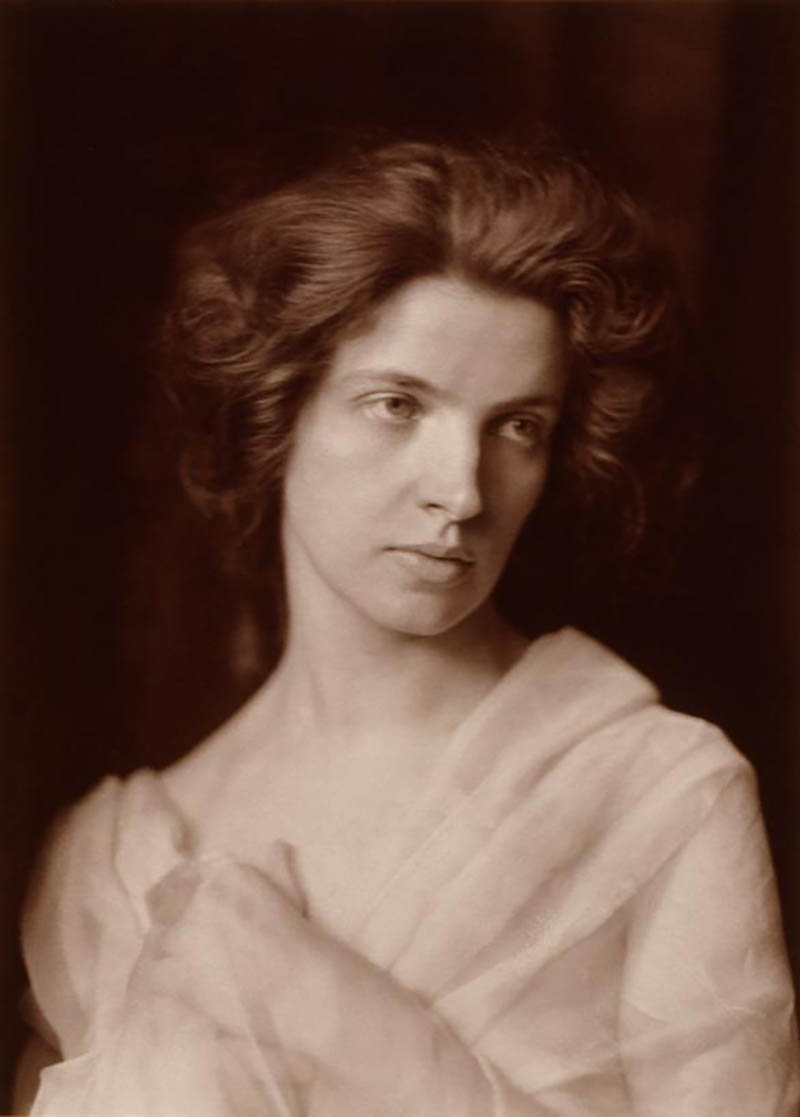

Ethereal, fragile, clean, innocent, like an ancient muse. An unnamed beauty in portraits taken by Alfred Nybom in Berlin in the early 20th century. The descriptions I could have previously combined with these familiar collections now seem foreign, stale, and deadly boring. What would a bohemian sex symbol, a queer in Edwardian England, a versatile, controversial and intelligent, and scandalous artist sound like?

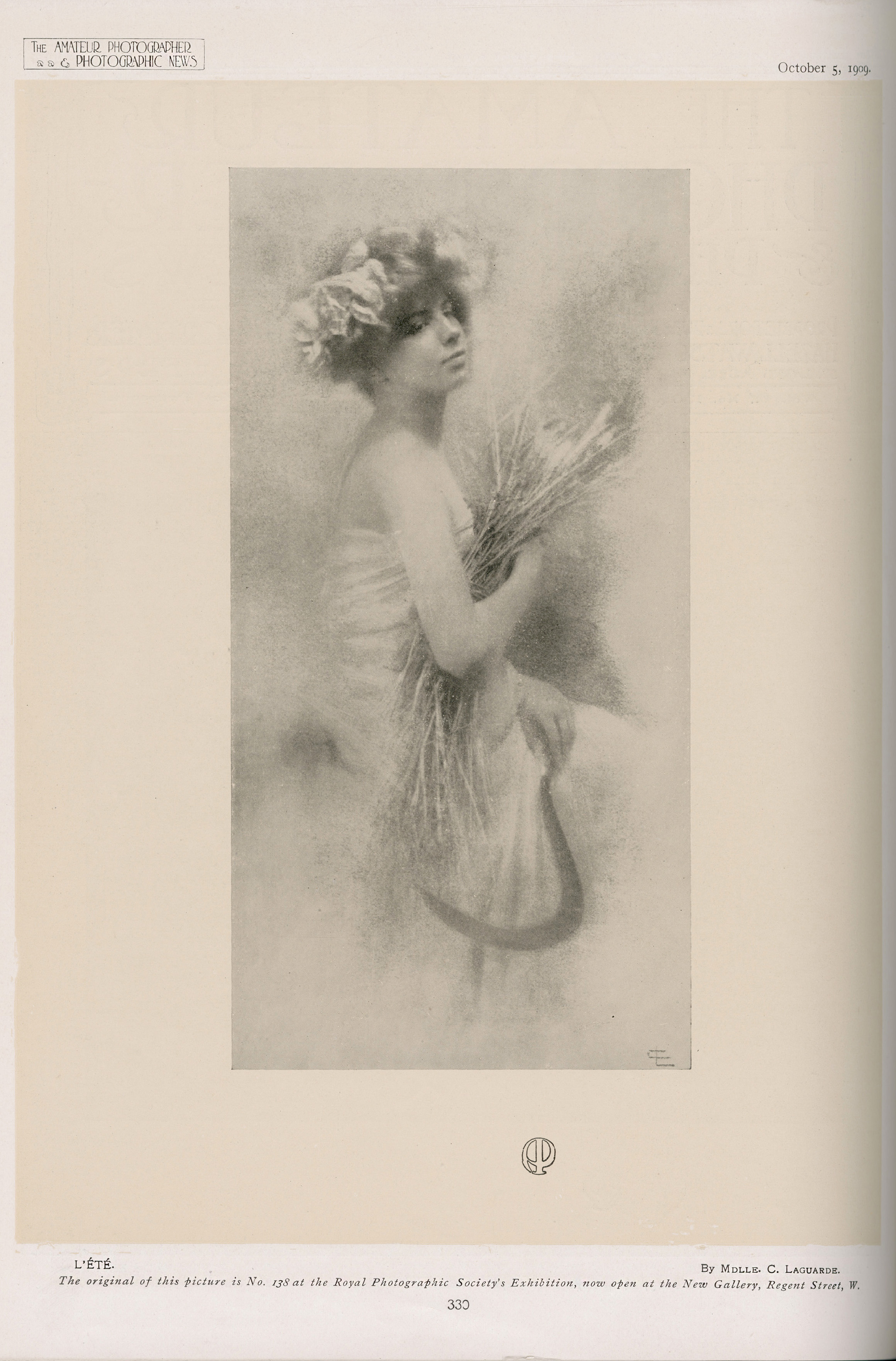

I may not have viewed the woman in the picture as an individual in the past, but she represented an archetype: a dreamlike and allegorical female figure in Belle Époque’s pictorialist photography. The generalized impression was shattered when the museum was contacted by a collector interested in theatrical photographs. That person had read about our Nybom collection. She said the woman in Nybom’s picture was Maud Allan.

At the museum, of course, we rejoiced when the iconic image got its name. At the same time, getting to know Allan’s life story changed my own attitude towards these images.

Beulah Maude Durrant was born in Toronto, Canada in 1873. In 1895, Durrant’s brother was convicted of the brutal murder of two young women. He was executed three years later. Durrant’s mother was a repressive figure whose incestal love for her son has long been rumored. To distance himself from his family, Durrant changed his name to Maud Allan and went across the Atlantic to Berlin to study to be a pianist.

Allan’s career as a pianist and opera singer was short and miserable, but she immediately adapted to the bohemian circles of Berlin and supported herself, among other things, by designing corsets and illustrating a sex guide for women. Allan didn’t find her self-expression in dance until he was 27 years old. Modern dance was a new and free art form that did not require lifelong practice. Allan developed an expression that revived, in her own words, the dance traditions of ancient Greece and the feminine movement in Renaissance paintings.

Allan wrote her memoir My Life and Dancing, which at the same time was a dissertation on dance as an art, in 1908. Her autobiography reflects a passionate approach to art, extensive reading, a sense of humor and a sharp intelligence. Allan spoke of her attitude towards dancing as a noble pure expression of emotion. At the same time, she completely ignored the controversial side associated with her personality. For example, she did not comment on the eroticism of her dance style.

Allan became known for her role as the greatest of the femme fatale, Salome, the seductress of the Bible. She identified with Salome and felt that she was essentially an innocent child suffering from her mother’s sins. Allan’s dance toward catharsis: breaking away from her difficult motherhood and bloody family history. Her masterpiece, the Shamelessly Sensual and Sexy Salome’s Vision (1906), based on thorough research, was a success. Allan had designed her own performance outfit.

Salome’s Vision also sparked protests over its eroticism, but with a few exceptions, the show avoided censorship. Allan managed to meet the needs of the time and combined oriental exoticism, eroticism, and high culture in a salon-friendly way. In 1907, after seeing Allan’s performance, King Edward himself invited Allan to England, where she lived for the next decade.

In her autobiography, Allan still wrote that most of the opposition and criticism she experienced came from other women. With the patriarchal control and repression of male sexuality by men, Allan came to face it in all its creepy in an episode that ruined her career.

Noel Pemberton Billing, a Member of Parliament, a champion of the moral purity of British society, published a paranoid and outrageous attack in the nationalist Imperialist newspaper in December 1917, with British war success at stake. According to Pemberton Billing, war enemy Germany was under the control of homosexuals. England, on the other hand, was full of spies who belonged to the secret society of German “spiritualists, whores, and homosexuals”. Maud Allan was among the named perverts. She had a relationship with the wife of the former British Liberal Prime Minister, according to Pemberton Billing, and the entire trio were minions of the enemy. Pemberton Billing, who himself had a German wife, continued on the obscene line when he wrote about Oscar Wilde’s play in 1918, in which Allan again performed Salome. After a performance in Paris, he painted threatening images of a “clitoris cult” of lesbian spies, claiming that the enemies of the state were at the forefront of Allan’s shameless performance.

The only true to the accusations was that Allan did indeed have intimate relationships with both men and women. Engaged in Germany, even engaged to a German sculptor, the bisexual and “fallen woman” who had connections to the politicians of the other party was a great target.

Allan sued Pemberton Billing for defamation. Surprisingly, he found himself on the defensive. The accused had excavated Allan’s grim family history and also considered this brother’s offense to be aggravating Allan’s identity. After revealing the painful secrets, Pemberton Billing asked the shocked Allan if she knew what the word clitoris meant. Allan’s positive response was taken as clear evidence of her sexual anomaly. Luckily, Pemberton Billing didn’t know Allan had drawn clitoris to a German sex guide 18 years earlier. The trial became a nutty circus, with no room for all the twists and turns in this context. Allan was witnessed by Oscar Wilde’s former, bitter lover, who sought revenge by dragging Wilde’s play into the bottom line. In addition, the slandered liberal politicians hired a young female agent to seduce Pemberton Billing and lead him to a brothel but failed. The agent fell in love with the attractive Pemberton Billing, changed sides and lied in favor of him in her testimony in court. Pemberton Billing was acquitted of all charges. The decision was made in the courtroom with shouts of joy as the women waved their handkerchiefs and the men threw their hats in the air.

The Salome mania of the early 20th century was over and the career of the disgraced Maud Allan collapsed. The aging female artist, known for her appearance, had no chance of re-creating herself. According to Allan’s biographer, she became a disappointed, useless, lying, exploitative, and even sadistic diva who lived a delusional life unable to let go of the glory of her youth. Maud Allan died almost forgotten in 1956 in the United States. We will never see these images again as before. The museum lost an unnamed and clean archetype, but was replaced by something much more interesting.

Roughly translated by us from source: Toisenlainen taiteilijakohtalo / A different kind of artist fate

Any correction, amend, or hint will be appreciated.