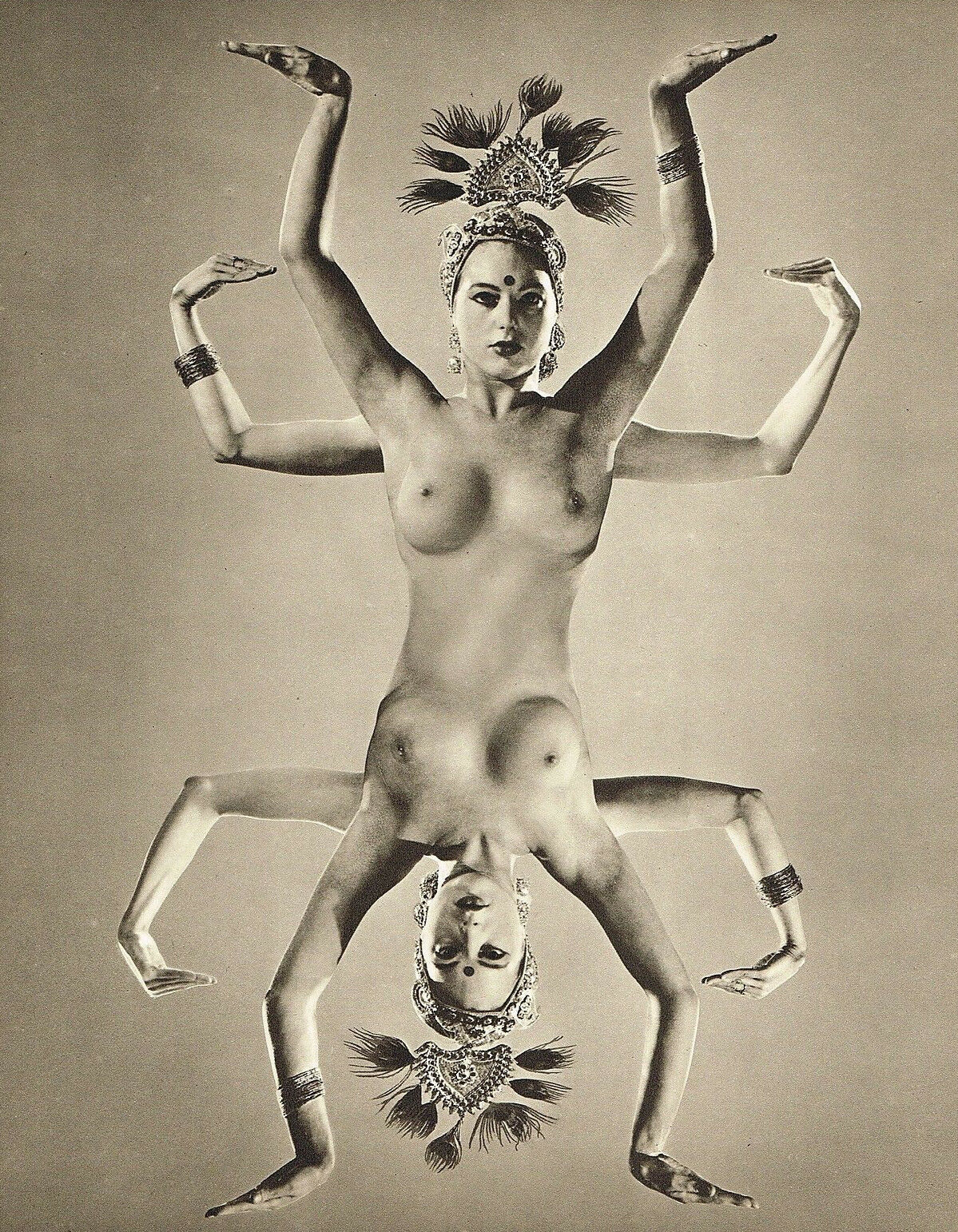

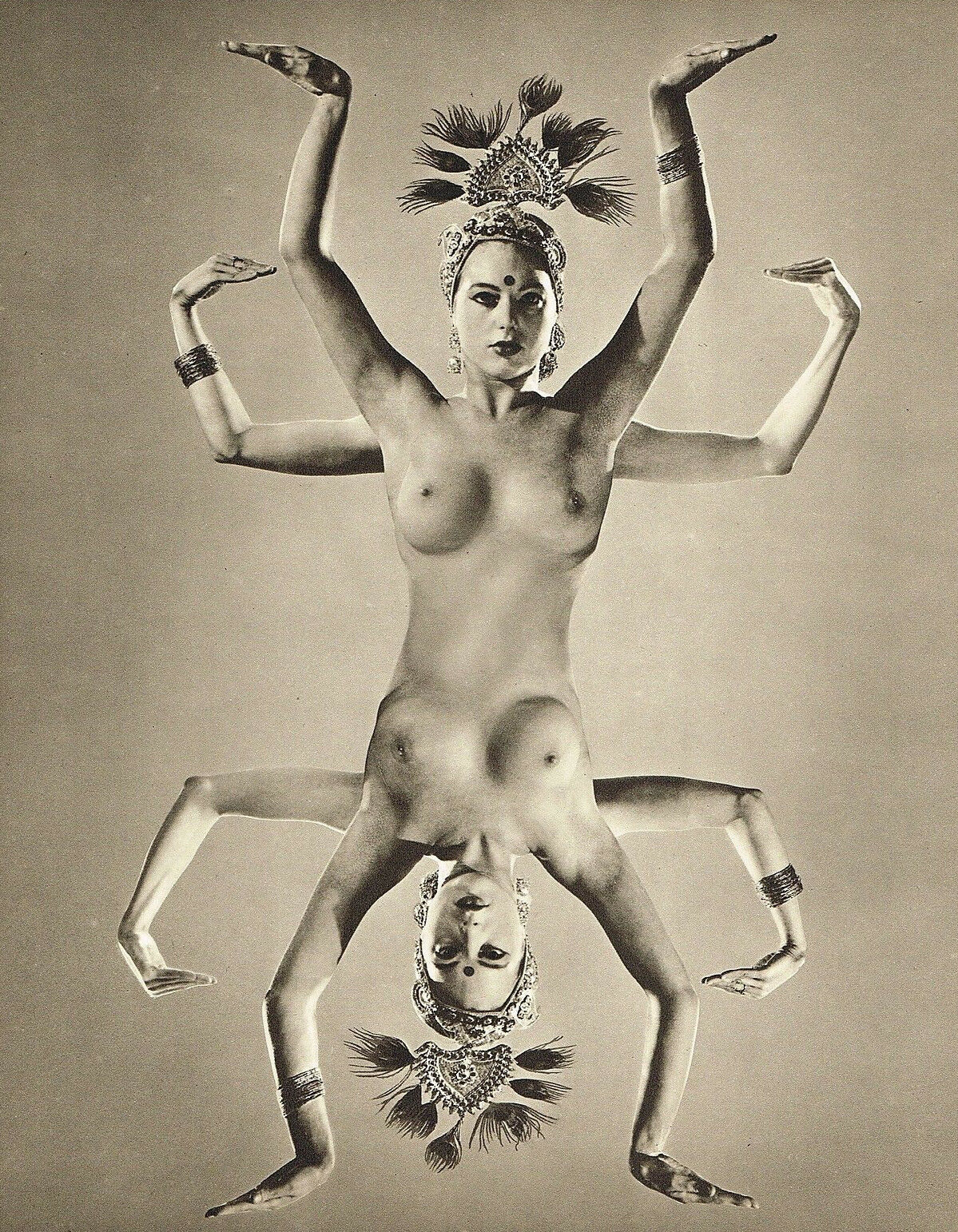

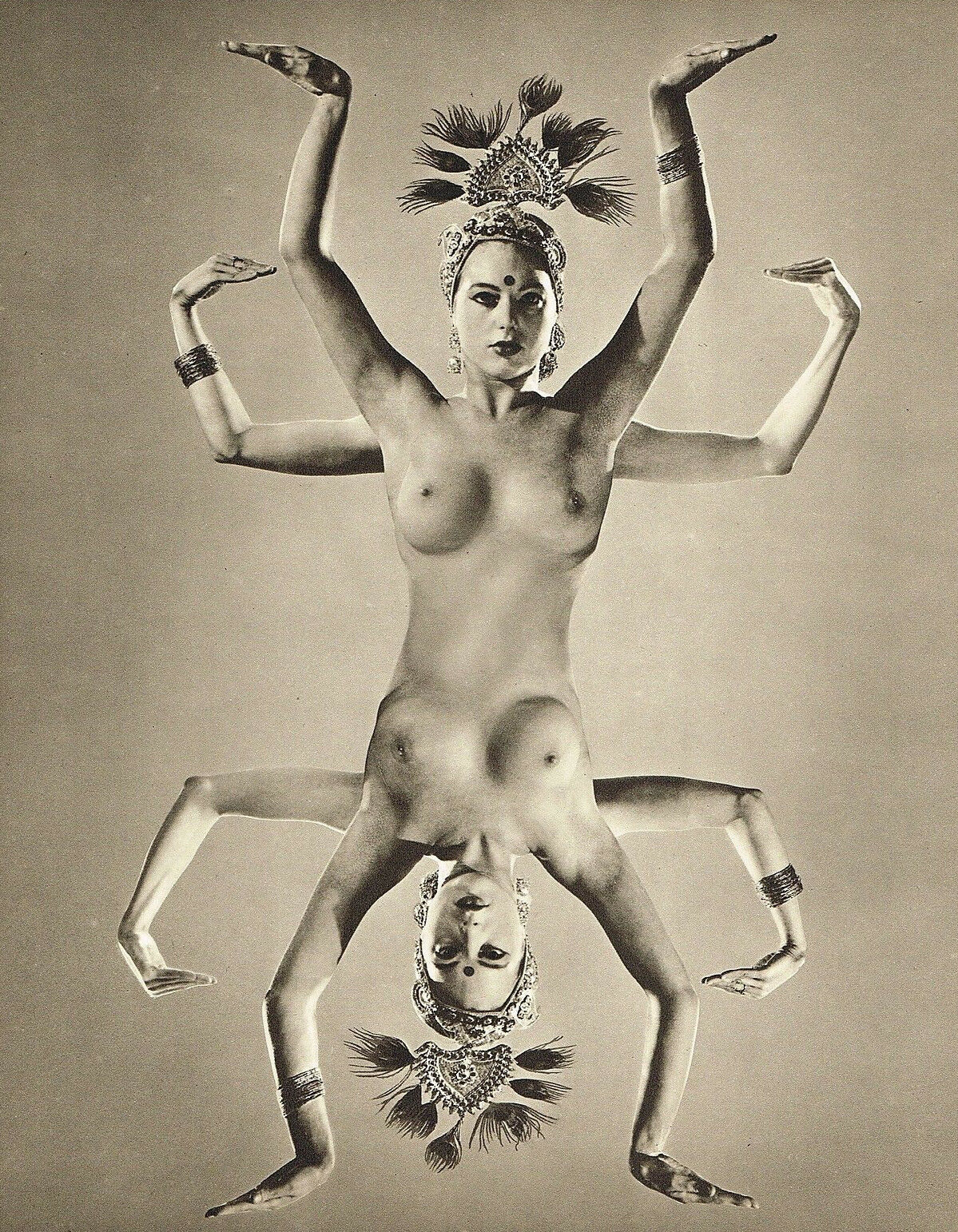

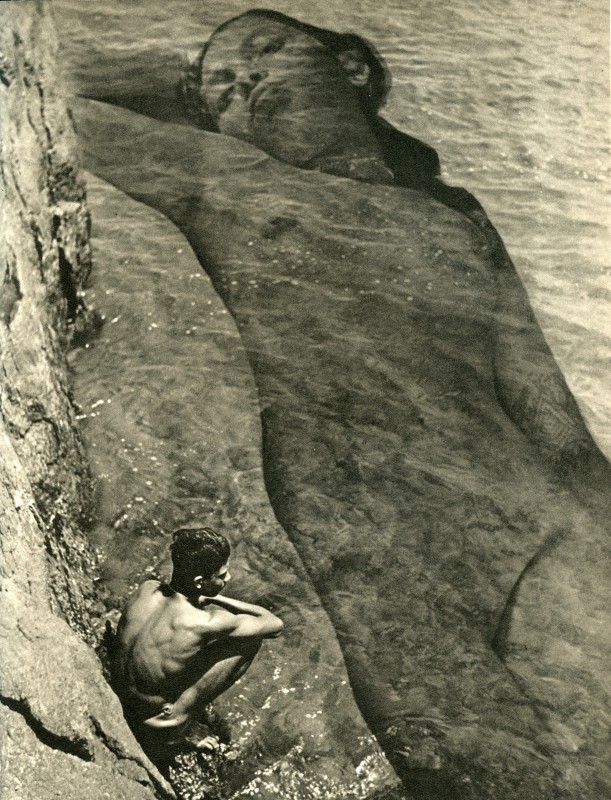

Hindu Goddess, 1950s

images that haunt us

»Destiny Emigration« reconstructs the stories of two Jewish photographers, Gerti Deutsch and Jeanne Mandello. Each left her country when the Nazis took power. | Das verborgene Museum

On July 15th, 1941 exiled German photographer Jeanne Mandello arrives in Uruguay

Among the people disembarking in Montevideo from the ship Cabo de Buena Esperanza (Cape of Good Hope) in July of 1941 was German-born photographer Jeanne Mandello, who had managed to escape from France. The two-month journey had been strenuous: hundreds of refugees fleeing Nazi Europe were on board, and individual berths had been sold several times each. On arrival in Montevideo, Jeanne Mandello weighed only 40 kilos (88 pounds). But Good Hope proved to be an auspicious name for Mandello’s transport from Europe, for Uruguay would become the country that saved her life.

Jeanne Mandello was born Johanna Mandello on October 18, 1907 in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. She studied photography at the Lette-Haus in Berlin, an institution dedicated to the professional training of women, and started working with a Leica camera in the late 1920s. She also trained for a year with Paul Wolff, the “Leica pioneer” who later became involved with the Nazi regime. She then opened her own photography studio in Frankfurt and from 1932 started working with her future husband Arno Grünebaum, who, under her direction, also became a photographer.

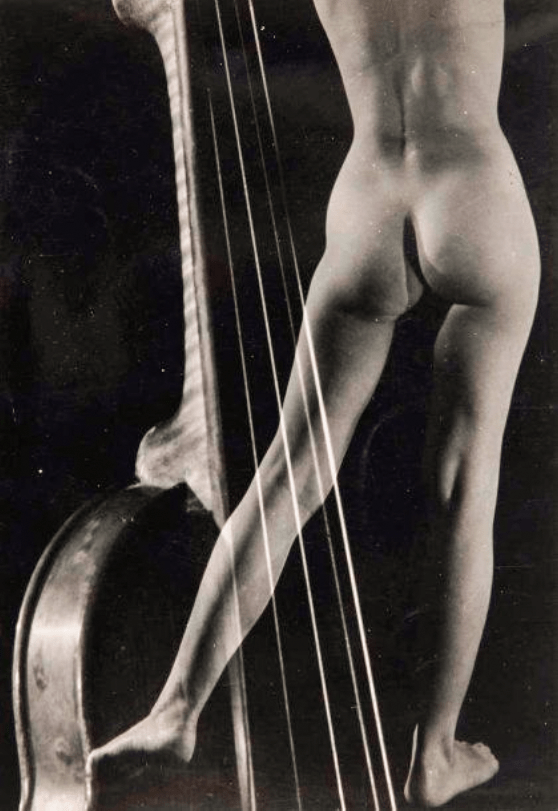

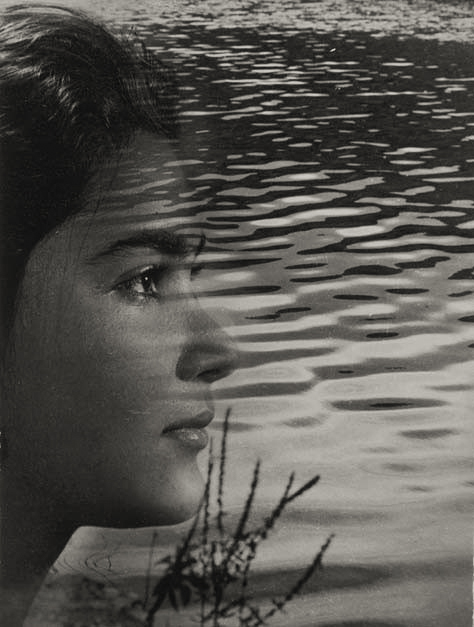

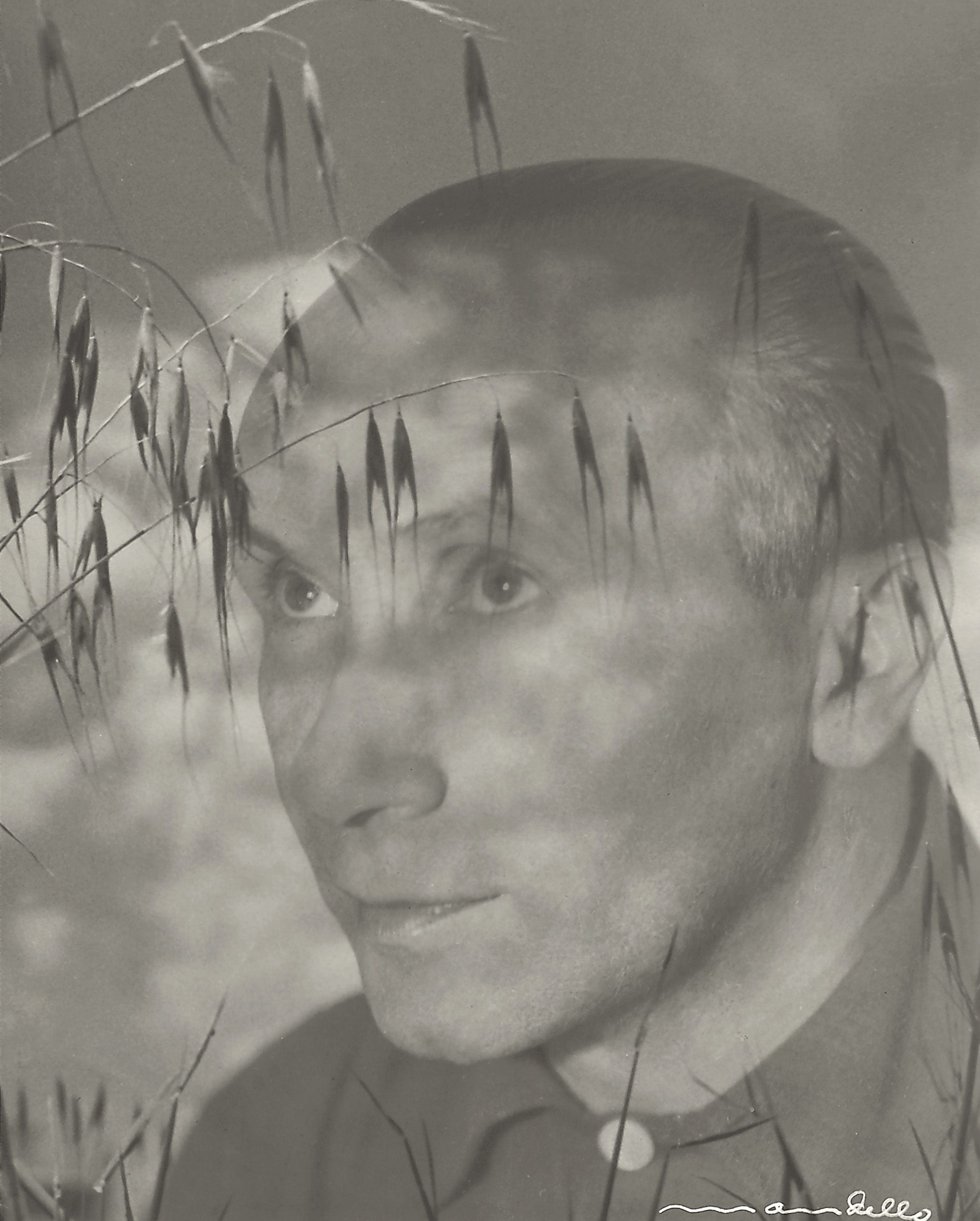

Fully aware of the dangers they faced, Jeanne and Arno left Nazi Germany for France in early 1934 and began a new life and career in Paris. The artistic avant-garde of the Weimar Republic and the Bauhaus school had inspired Mandello, and she became engaged by the Paris art scene where photographers like Man Ray and Brassaï redefined modern photography. Mandello started exploring new techniques, unusual angles, framings, and lighting. Like fellow exiled photographers Erwin Blumenfeld and Hermann Landshoff, the couple established themselves as fashion photographers, opened a photography studio. They worked for fashion labels such as Balenciaga and Guerlain and the magazines Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and Fémina. Johanna changed her name to the French “Jeanne,” and on October 28, 1940 the Third Reich revoked her German citizenship.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, Jeanne and Arno had to leave Paris. First threatened by the French Republic as “foreign enemies,” Jeanne was sent to the village of Dognen, near the camp of Gurs. She had to leave everything behind and lost her equipment and her entire body of work. Realizing they were in great danger in Vichy France, the couple managed to get exit permits from France, visas for Uruguay, and ship passage from Bilbao to Montevideo. (*)

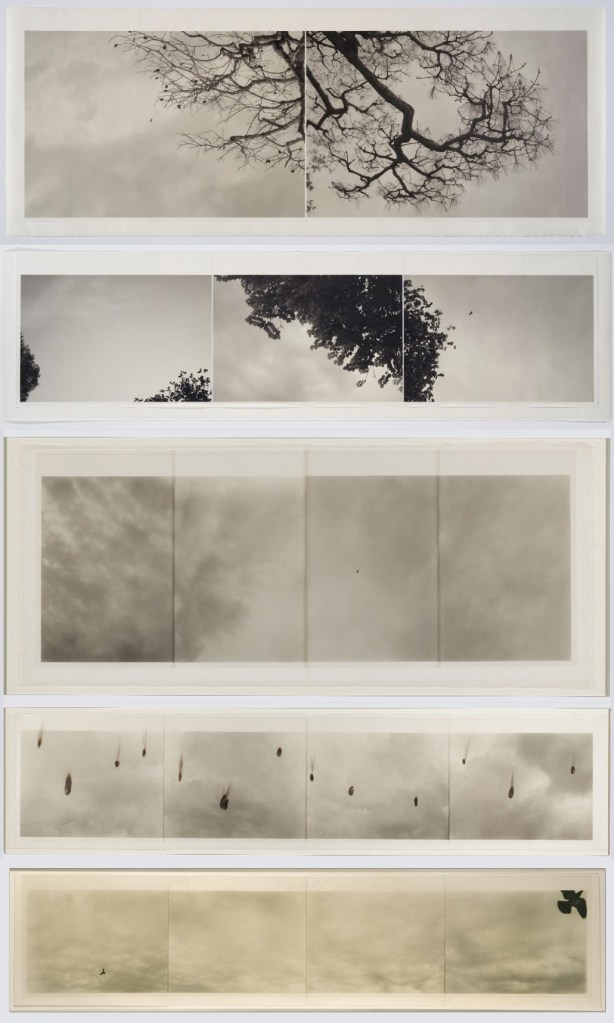

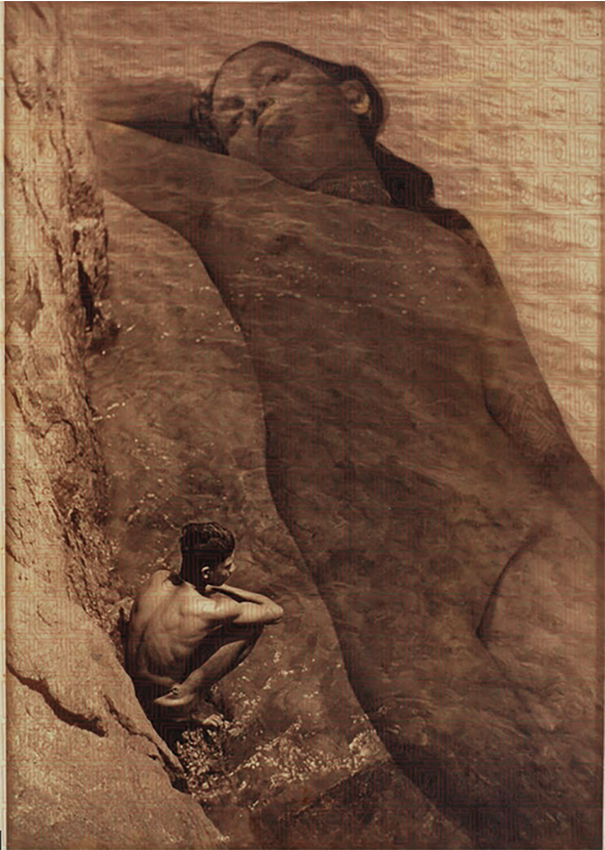

Jeanne and Arno immediately fell in love with Uruguay. With just three million inhabitants, the country took in approximately 10,000 German-speaking émigrés during the Second World War, most of them Jewish. Jeanne commented later, “I have never met such kind and obliging people as the people in Uruguay … Everybody helped us.” She quickly made contacts and established herself as a successful photographer. From 1943, she regularly exhibited her work: portraits, landscapes, architecture shots, solarisations (photographs with very strong overexposure), and photograms (the direct exposure of photosensitive surfaces without using a camera). Her South American photography is a perfect example of the mutual influence and cultural exchange between the Old World and the New which contributed to the modernization of South American cultural life. Jeanne was in close contact with Uruguayan artists and intellectuals as well as with other exiles from Europe in Montevideo and Punta del Este. They included painter Joaquín Torres García, poets Rafael Alberti and Jules Supervielle, photographer Florence Henri, sculptor Eduardo Yepes, art critic Julio Payró, and journalist J. Hellmuth Freund, who published an article on the Mandellos in Susana Soca’s art magazine Entregas de la Licorna. Jeanne’s eclectic work was in tune with the progressive and modernist urban and artistic developments emerging at that moment in Uruguay, and she became one of the country’s precursors of modern photography, similar to Grete Stern in Argentina. In 1952, Jeanne’s work was exhibited at Rio de Janeiro’s Museum of Modern Art.

In 1954 Jeanne and Arno separated, and she left Uruguay for Brazil to join her future second husband, journalist Lothar Bauer, an old acquaintance from Frankfurt. At the end of the 1950s, the couple moved to Barcelona, where Jeanne would live until the end of her life. In 1970, she adopted a daughter, Isabel. She kept working until the end of her life, documenting the city of Barcelona and never tiring of her favorite motif of woods and trees. Jeanne Mandello died in Barcelona on December 17, 2001. (*)

Most of Jeanne Mandello’s early work has been lost. Her Paris studio was emptied and pillaged by the National Socialist Dienststelle Westen in 1942, its negatives and archives probably destroyed.

In 1997, an exhibition of her work was held in Barcelona, and the exhibit Jeanne Mandello: Imágenes de una fotógrafa exiliada (Images of an Exiled Photographer) toured through several cities in Uruguay and Argentina in 2012 and 2013.

Jeanne Mandello was forced by circumstance to become a cosmopolitan artist and had to re-invent herself and her photography many times. Trained in Germany and influenced by the French avant-garde movements of the 1930s, she brought the geometry of the Bauhaus and the surrealist fantasy of pre-war Paris to her new homes in Uruguay, Brazil, and Spain. Forgotten for nearly 50 years because of the historical circumstances surrounding her life, she is today rediscovered as an avant-garde female artist and a pioneer in the field of modern photography. (*)

(*) quoted from Jewish Women’s Archive [JWA]

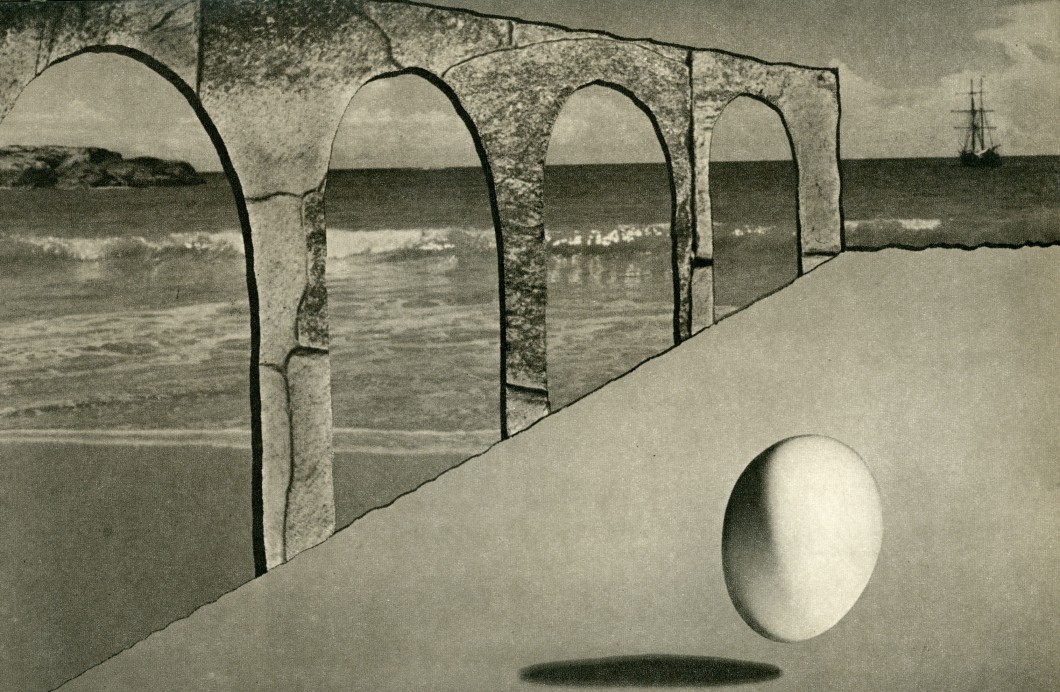

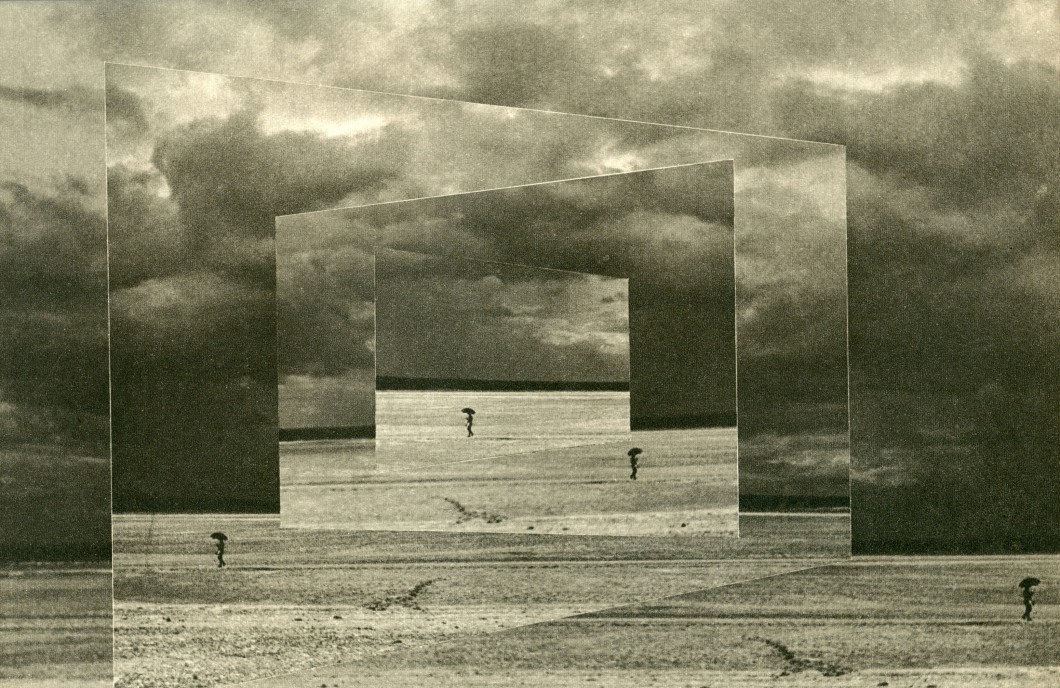

Wendt’s photomontage has been most conventionally and variously comprehended through its pastiche of influences and motifs such as De Chirico’s futurist arches, Magritte’s “Ceci n’est pas un oeuf,” Piero della Francesca’s Brera Madonna, Georges Bataille’s rumination on the story of the eye, and the recurrent vignette of a distant brig. Although he clearly held great admiration for those artistic circles he came into contact with in Europe, it seems a bit too summary merely to insert him within these narratives. (quoted from source)

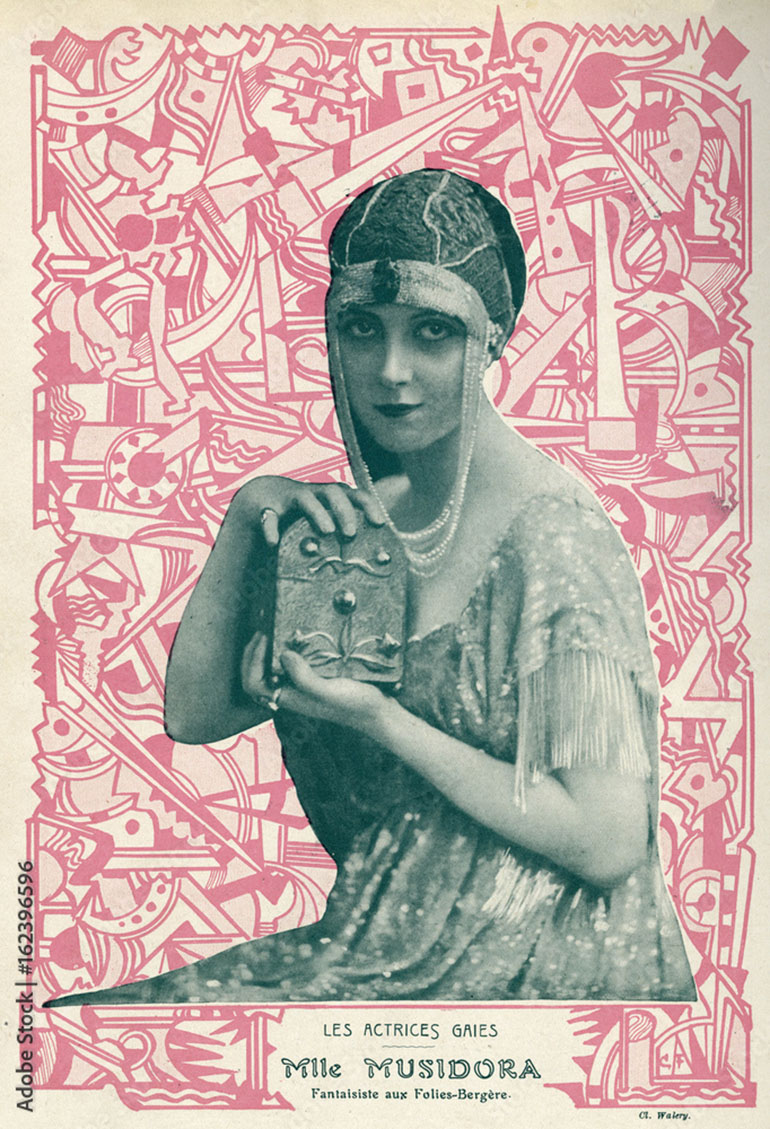

Fantaisiste aux Folies Bergère, portrait dédicacé et signé « Pour Milon, Musidora, dans ce coffré [sic] précieux, il y a un maillot de milon », vers 1912. Photographie par Waléry, tirage argentique d’époque (ovale), monté sur un carton du studio, signature de l’auteur sur l’image. | src Artprecium : 370 photographies de cinema pour tous 7e. edition / lot 11: Mlle. Musidora

The image above is also hosted in wikimedia, there the image is dated 1912 and credited to Lucien Waléry.