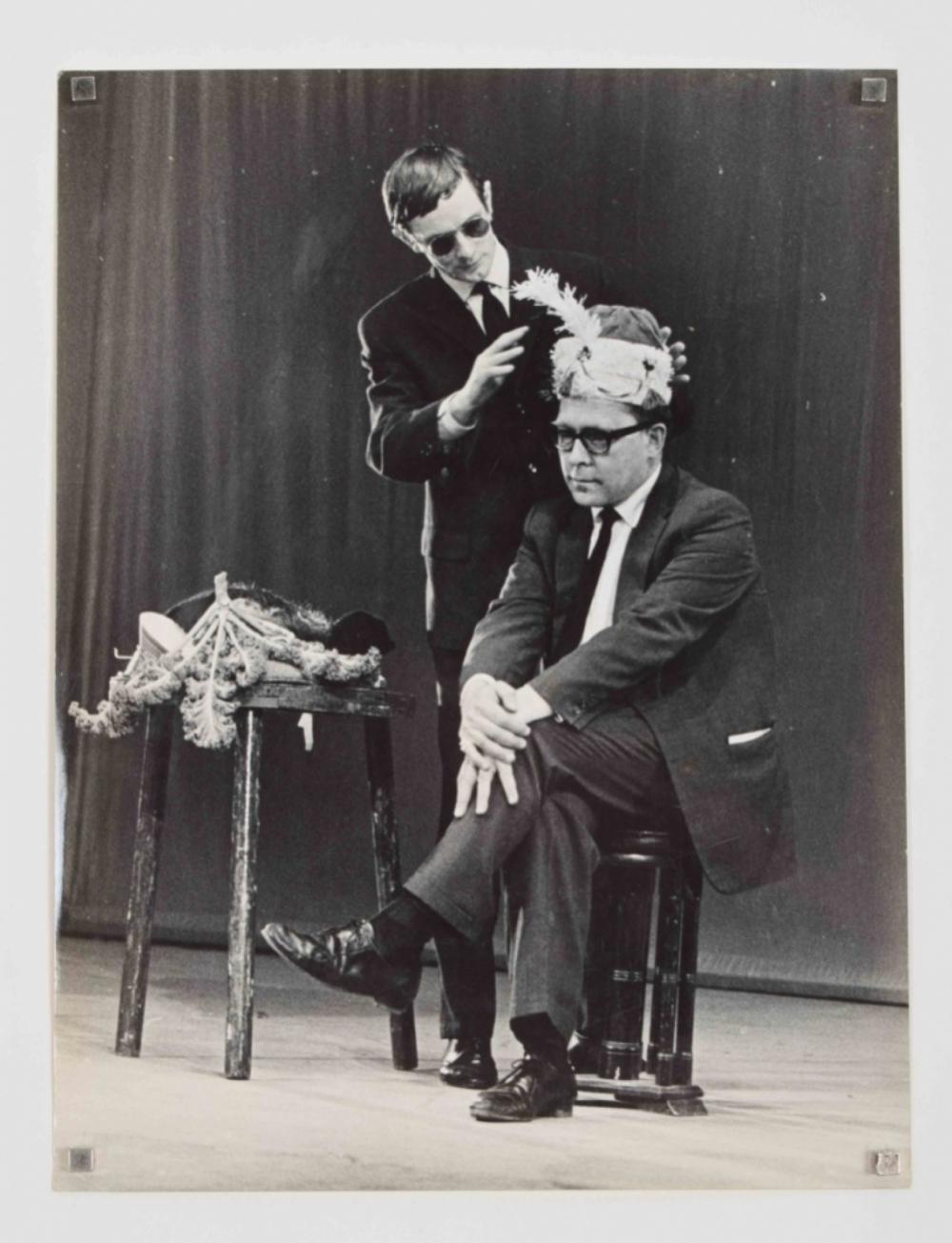

Nieuwste Literatuur, De Kleine Komedie, Amsterdam, December 18, 1963 | src MoMA

Theater/Nieuwste Literatuur, De Kleine Komedie, Amsterdam, December 18, 1963 | src MoMA

images that haunt us

When the autochrome — the Lumière brothers’ new colour photographic process — reached New Zealand in 1907, it was eagerly adopted by those who could afford to use it. Among them was Auckland photographer Robert Walrond, whose ‘Cleopatra’ in Domain cricket ground is among a small number of superb early colour photographs in Te Papa’s collection. The combined effect of the sun and wind on the women’s costumes and in the fluttering appearance of the silk scarf held above the Cleopatra character is stunning. The tableau is interrupted but undiminished by what appears to be a pipe band in uniform in the background. The women were very likely part of what was described by the New Zealand Herald as a ‘fine’ performance of Luigi Mancinelli’s Cleopatra (a musical setting of the play by Pietro Cossa), associated with the Auckland Exhibition of 1913–14 held in the Domain.

The story of Cleopatra — with a particular focus on her love life and tragic death — was an exotic but respectable theme for theatre and dress-up events for women at the time. The Cleopatra myth and look were popularised by international performers such as the frequently-photographed Sarah Bernhardt in France and by numerous stage productions and films from the late nineteenth century onwards. With the advent of photography, part of performing the role became having a portrait made while in costume. The arrival of the autochrome was greeted with excitement and anticipation because rich colours could now be captured and the elaborate style of the costumes enhanced.

Much was made of the impact the autochrome would have on art and the role of photography within it. However, one of the disadvantages of the process was that it involved a unique one-off image on a glass plate: this required projection to be viewed and couldn’t be exhibited. So despite the original excitement for the method, it slipped out of sight once new developments arrived that fixed colour printing on a paper format. Walrond’s set of autochromes held by Te Papa are one of only a few larger bodies of work by New Zealand practitioners of this process.

Lissa Mitchell – This essay originally appeared in New Zealand Art at Te Papa (Te Papa Press, 2018)

The American dancer Loie Fuller (1862-1928) conquered Paris on her opening night at the Folies-Bergère on November 5, 1892. Manipulating with bamboo sticks an immense skirt made of over a hundred yards of translucent, iridescent silk, the dancer evoked organic forms –butterflies, flowers, and flames–in perpetual metamorphosis through a play of colored lights. Loie Fuller’s innovative lighting effects, some of which she patented, transformed her dances into enthralling syntheses of movement, color, and music, in which the dancer herself all but vanished. Artists and writers of the 1890s praised her art as an aesthetic breakthrough, and the Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé, who saw her perform in 1893, wrote in his essay on her that her dance was “the theatrical form of poetry par excellence.” Immensely popular, she had her own theater at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, promoted other women dancers including Isadora Duncan, directed experimental movies, and stopped performing only in 1925.

Loie Fuller’s whirling, undulating silhouette, which embodied the fluid lines of Art Nouveau, inspired many images, from the portraits of Toulouse-Lautrec and the posters of Jules Chéret and Alphonse Mucha to the sculptures of Pierre Roche and Théodore Rivière, as well as the photographs of Harry C. Ellis and Eugène Druet.

The pictures shown here depict movements from such dances as “Dance of the Lily” and “Dance of Flame.” These images do not pretend to evoke the otherworldly effect of the performance, which took place on a darkened stage in front of a complex set of mirrors and whose magic was entirely dependent on lighting. Here, the strange shapes, reminiscent of chalices and butterflies, take form, incongruously, in the middle of an urban park, through the efforts of a short, stout figure. Arrested in crude natural light, they still retain, however, their spellbinding energy. Part of a group of thirteen photographs complemented by six others in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, these images belonged to the sculptor Théodore Rivière (1857-1912), and were previously thought to have been made by him. They have now been reattributed to Samuel Joshua Beckett, a photographer working in London. / quoted from the Met

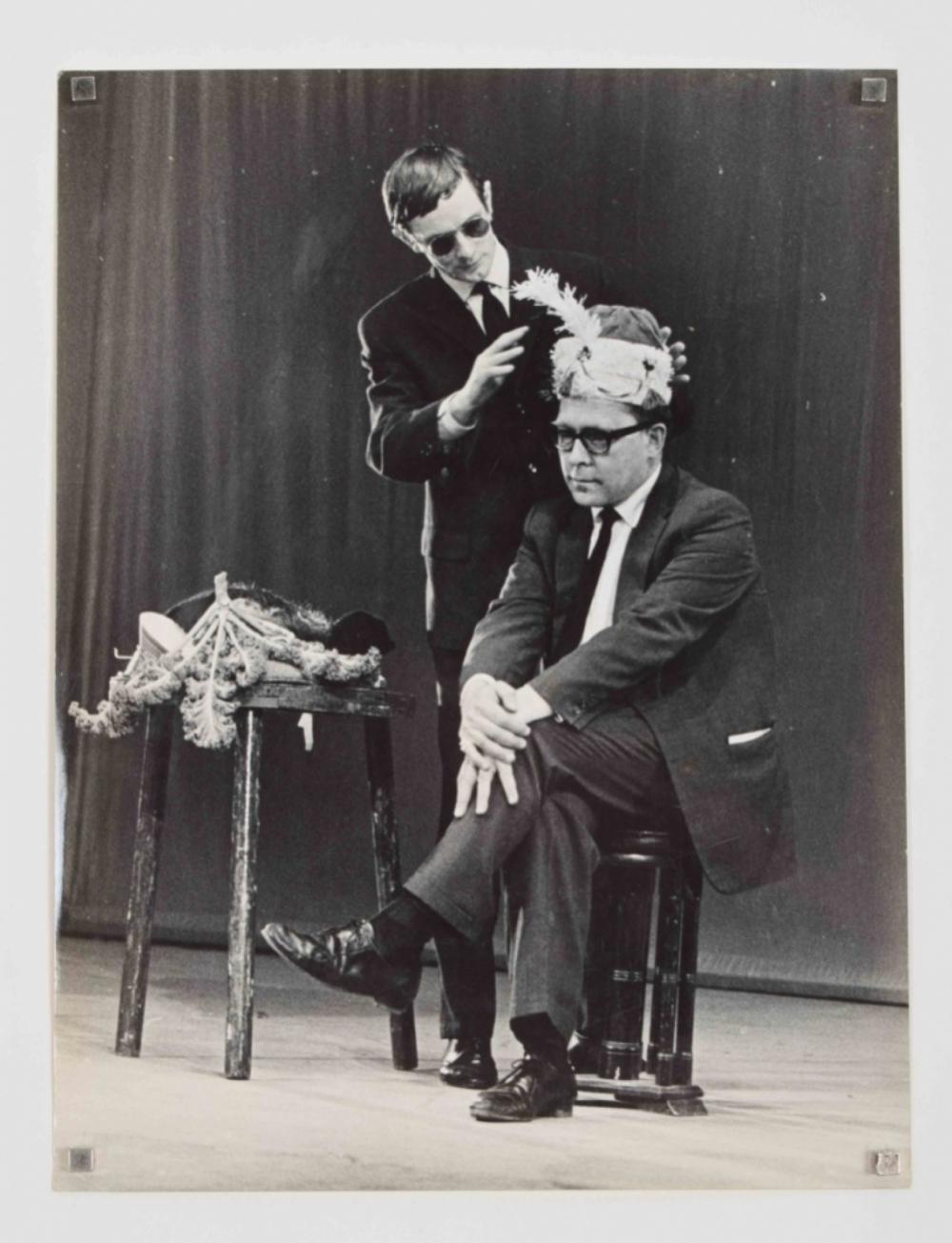

Esther Ferrer :: Íntimo y personal (Intimate and Personal), 1977 [Work consisting of a score of 21 photographs. Performance]

The performance offered the participants the possibility of measuring parts of the body, their own and others. The artist herself claimed that the piece was based on the phallocentric need for checking and measuring. more here [+]

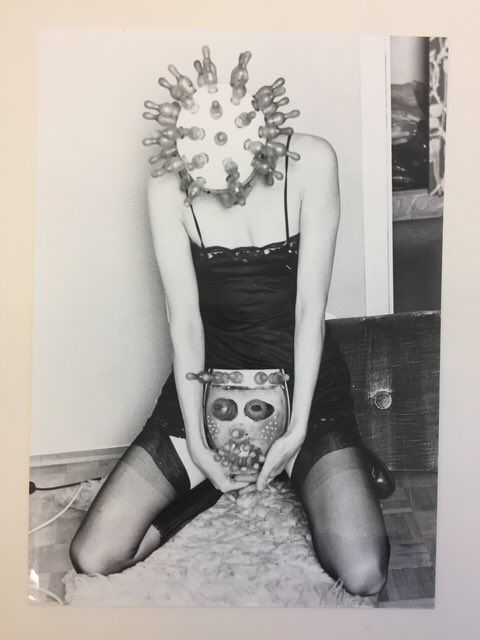

Medium at a parlour sceance, 1912. | src instagram