images that haunt us

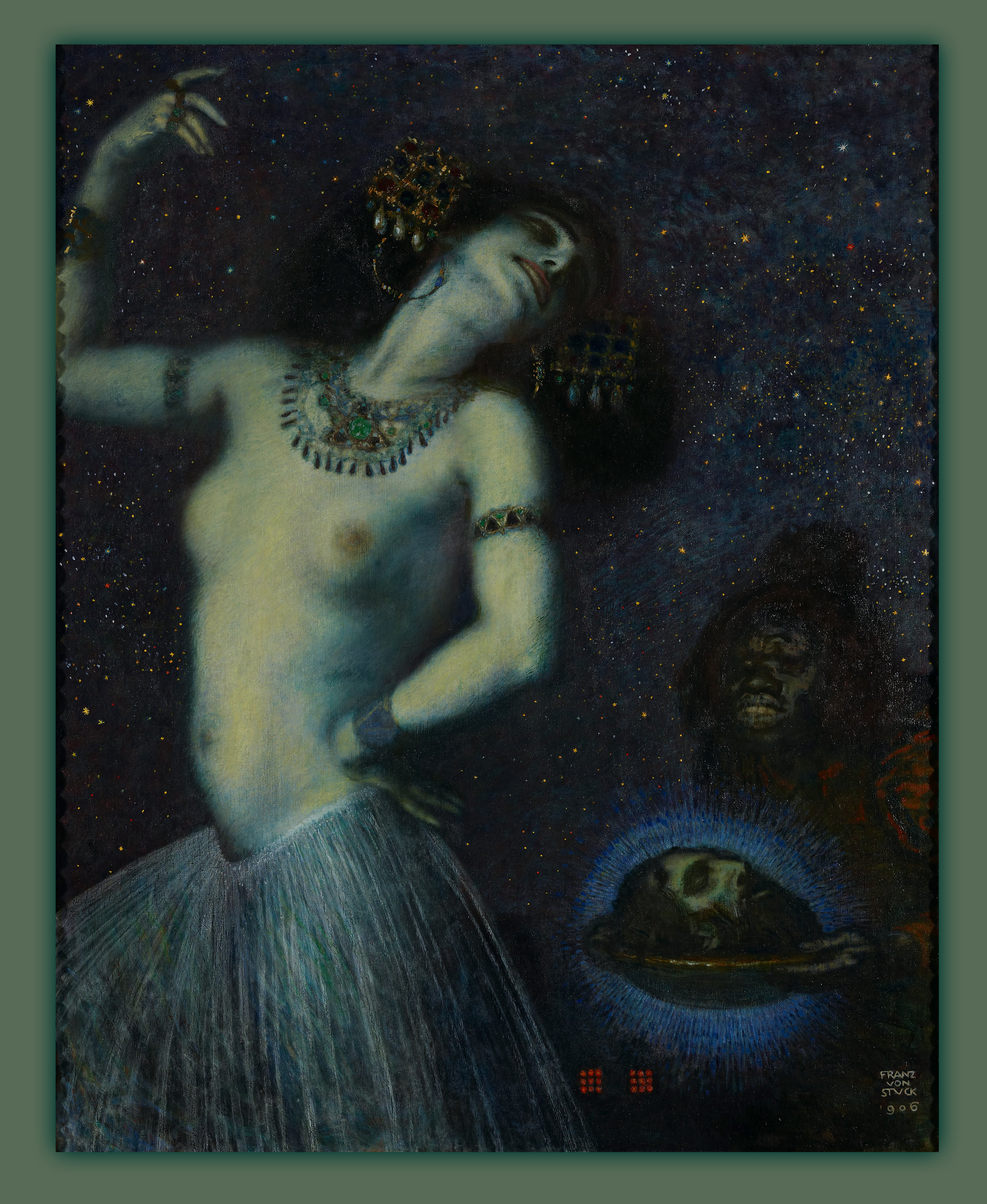

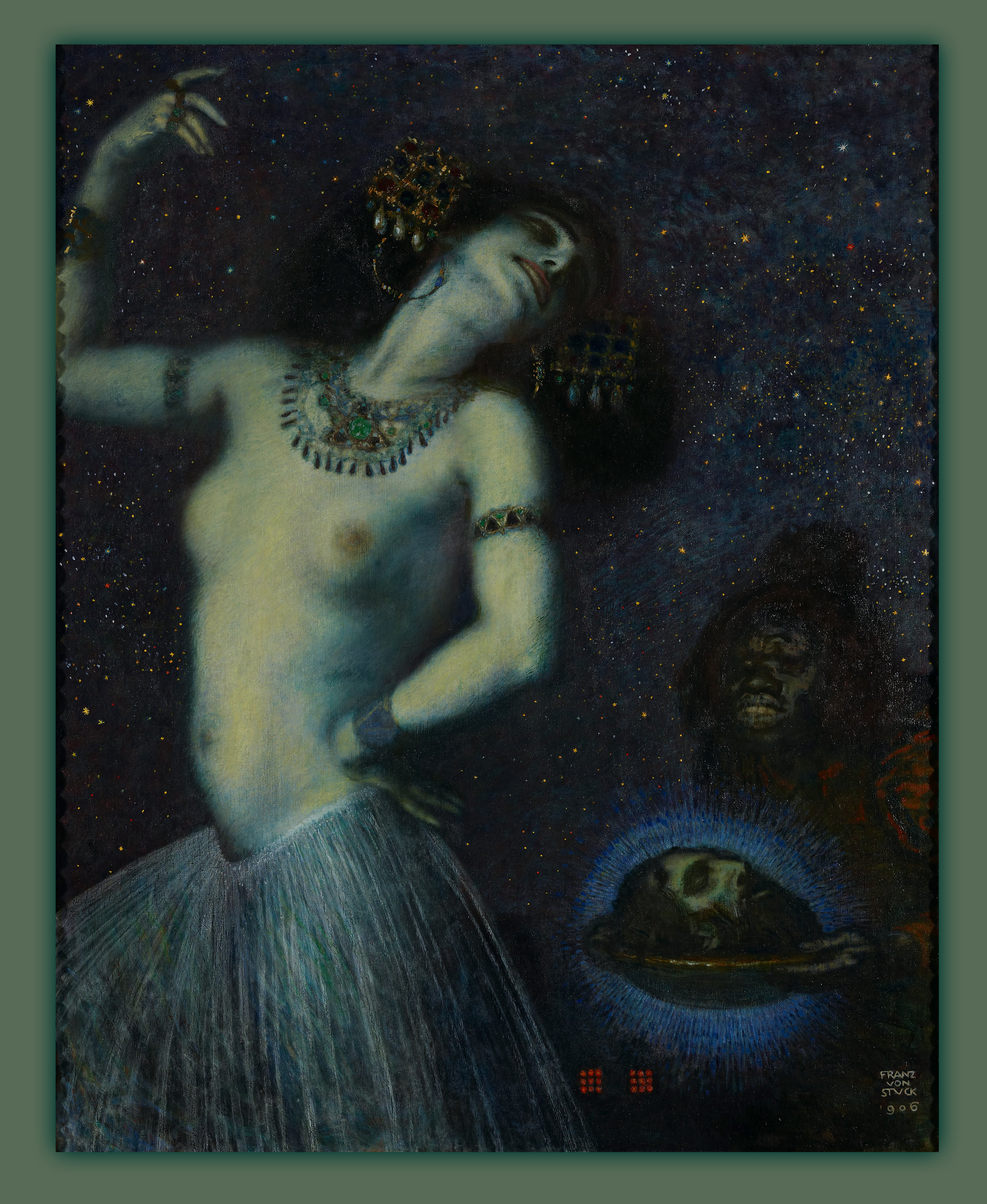

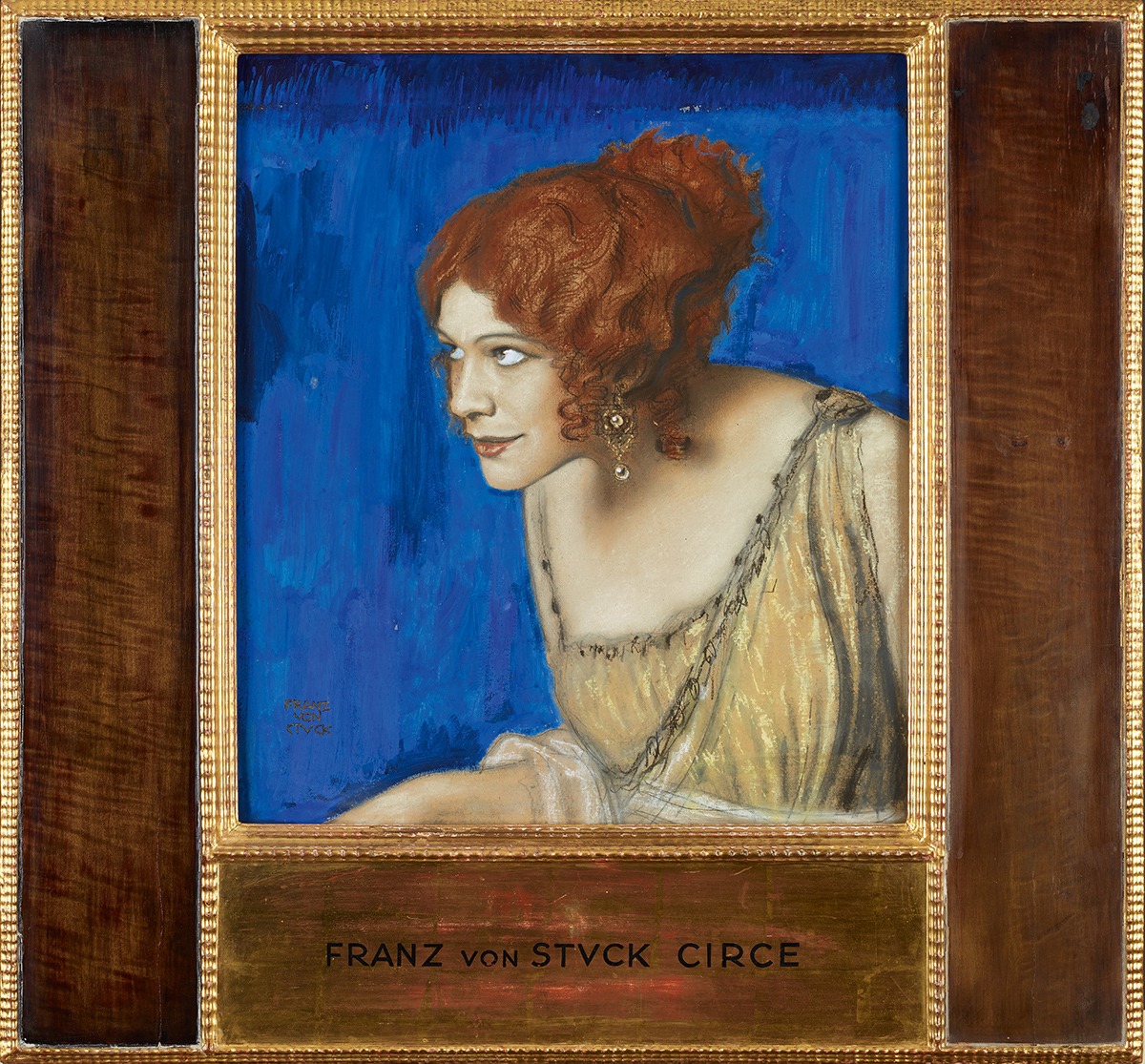

Als Schauspielerin wurde die in Wien als Ottilie Godefroy geborene Tilla Durieux (1880–1971) ab 1903 an der Bühne von Max Reinhardt in Berlin berühmt. Sie ist vielfach dargestellt worden, allein drei Künstler widmeten sich dieser Aufgabe im Jahre 1912: Ernst Barlach modellierte auf Wunsch von Paul Cassirer, dem zweiten Ehemann Durieux’, eine Büste, die noch im selben Jahr in Porzellan und in Bronze gegossen wurde. Ebenfalls 1912 stellten Hugo Lederer und Stuck sie in der Rolle der Circe aus dem gleichnamigen Stück von Pedro Calderón dar, mit der sie im Münchner Künstlertheater großen Erfolg hatte. Lederer schuf eine Statue. Stuck ließ die Schauspielerin, entsprechend einer häufig von ihm angewandten Arbeitsweise, in seinem Atelier fotografieren, in für das geplante Bild effektvollen Posen. Eine dieser fotografischen Studien (Nachlass Franz von Stuck, Nr. 47 A, Museum Villa Stuck, München) diente dem Gemälde als direkte Vorlage. Im Bild hebt sich Tilla Durieux als Circe in scharfem Profil vom dunklen Grund ab. Gleichermaßen schön und gefährlich, mit lauernd-lockendem Blick reicht sie ihrem imaginären Gegenüber eine goldene Weinschale. Else Lasker- Schüler dichtete: „Barlach formte den Kopf / In bläulich Porzellan, / Als Kleopatra malte sie Slevogt. / Senken sich ihre witternden Vogelaugen, / Dann schwankt die Bühne vor Todesbeben: / Alkestis“ (Der Querschnitt, 2. Jg. [1922], Weihnachtsheft, S. 179). Die suggestive Darstellung suchte Stuck mit einem eigens entworfenen Rahmen noch zu verstärken. | Angelika Wesenberg für Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

SEE ALSO: Malerei und Photographie im Dialog von 1840 bis heute. Ausstellung im Rahmen der Junifestwochen, Zürich, Kunsthaus Zürich, 13.05.1977-24.07.1977

Tilla Durieux (1880-1971), born Ottilie Godefroy in Vienna, became famous as an actress from 1903 on the stage of Max Reinhardt in Berlin. She has been depicted many times, with three artists dedicated to this task in 1912: Ernst Barlach modeled a bust at the request of Paul Cassirer, Durieux’s second husband, which was cast in porcelain and bronze that same year. Also in 1912, Hugo Lederer and Stuck presented her in the role of Circe from the play of the same name by Pedro Calderón, with which she had great success at the Munich Art Theater. Lederer created a statue. Stuck had the actress photographed in his studio, in accordance with a working method he often used, in effective poses for the planned picture. One of these photographic studies (Franz von Stuck estate, no. 47 A, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich) served as a direct template for the painting. In the picture, Tilla Durieux as Circe stands out in sharp profile against the dark background. Equally beautiful and dangerous, with a lurking, alluring look, she hands her imaginary counterpart a golden wine bowl. | From Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

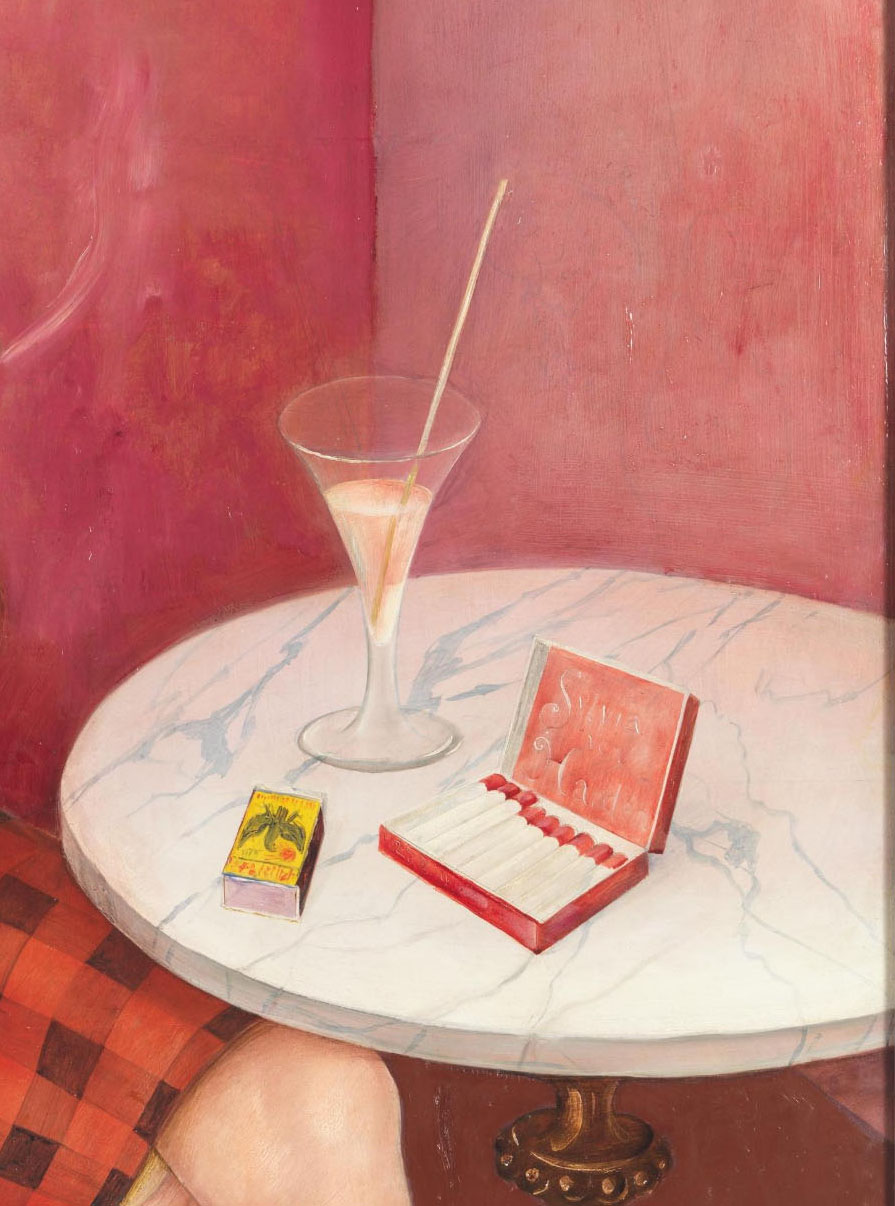

Journaliste à Berlin dans les années 1920, Sylvia von Harden (1894-1963) s’affiche en intellectuelle émancipée par une pose nonchalante. Otto Dix contrarie son arrogance par le détail d’un bas défait. Sa robe-sac à gros carreaux rouges détonne avec l’environnement rose, typique de l’art nouveau. Le style réaliste, froid et satirique est caractéristique du mouvement de la Nouvelle Objectivité [Neue Sachlichkeit] auquel appartient le peintre. Il s’inspire des maîtres allemands du début du 16e siècle (Grünewald, Cranach et Holbein), par la technique de la tempera sur bois et l’exhibition d’une intéressante laideur. | src Centre Pompidou

Sylvia von Harden (1894-1963) was a journalist in Berlin in the 1920s. Her nonchalant stance is a statement of her emancipated intellectual role. Otto Dix undermines her arrogance with the detail of a loose stocking and her rather awkward pose. Her red-checkered sack dress contrast with the pink environment, typically Art Nouveau. The cold, satirical realism typifies the New Objectivity [Neue Sachlichkeit] movement to which the painter belonged. lnspired by early 16th-century German masters (Grünewald, Cranach and Holbein), he embraced the tempera on wood panel technique as well as the choice to exhibit the ugliness. | src Centre Pompidou

Installé à Berlin entre 1925 et 1927, Dix peint une série de portraits remarquables. Maintes fois reproduit et exposé, celui de la journaliste Sylvia von Harden, de son vrai nom Sylvia Lehr (1894-1963), est l’un des plus fascinants. Il offre une véritable synthèse d’une recherche picturale qui s’inscrit dans ce que le critique Gustav Hartlaub désigne comme « l’aile gauche vériste » de la Neue Sachlichkeit [Nouvelle objectivité]. La représentation sans complaisance d’un type humain à travers ses attributs s’exprime dans le choix d’une intellectuelle émancipée des années 1920, aux allures masculines, fumant et buvant seule dans un café. […] L’image de la journaliste, que Dix a rencontrée au Romanische Café, haut-lieu berlinois du monde littéraire et artistique, reste pourtant ambiguë. Si dans ses souvenirs publiés à la fin des années 1950, la journaliste émigrée à Londres affirme que Dix l’a choisie pour son allure, représentative de cette époque, il semble que l’artiste la montre aussi en porte-à-faux par rapport à un type et un rôle dans lesquels elle paraît mal à l’aise. Sa pose nonchalante, mais peu naturelle, paraît trop ostentatoire ; son arrogance intellectuelle est contrariée par l’image de son bas défait ; et sa robe-sac à gros carreaux rouges l’oppose à l’environnement rose Art nouveau. Cette mise à nu semble avoir échappé au modèle. | src Centre Pompidou

Living in Berlin between 1925 and 1927, Dix painted a series of remarkable portraits. Reproduced and exhibited many times, that of the journalist Sylvia von Harden, whose real name was Sylvia Lehr (1894-1963), is one of the most fascinating. It offers a true synthesis of pictorial research which is part of what the critic Gustav Hartlaub designates as the “verist left wing” of the Neue Sachlichkeit [New Objectivity]. The uncompromising representation of a human type through its attributes is expressed in the choice of an emancipated intellectual from the 1920s, with masculine appearance, smoking and drinking alone in a café. […] The image of the journalist, whom Dix met at the Romanische Café, a Berlin hotspot for the literary and artistic world, nevertheless remains ambiguous. In her memories published at the end of the 1950s, the journalist who emigrated to London affirms that Dix chose her for her appearance, representative of that era, but it seems that the artist also shows her cantilevered from to a type and a role in which she seems uncomfortable. Her nonchalant, but unnatural pose seems too ostentatious; her intellectual arrogance is thwarted by the image of her undone stockings; and her large red check sack dress contrasts with the pink Art Nouveau environment. This exposure seems to have escaped the model.

Angela Lampe. Extrait du catalogue Collection art moderne – La collection du Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne , Paris, Centre Pompidou, 2007