images that haunt us

This portrait by Cecilia Beaux portrays the artist’s cousin, Sarah Allibone Leavitt, dressed in white with her black cat on her shoulder. Beaux was recognized not only for her bold painting technique, but also for her ability to imbue her female subjects with wit and intelligence, rendering them more than just mere objects of beauty. A student in Paris in the late 1880s, the artist was influenced by her firsthand exposure to French impressionism. Her light-filled palette and gestural style invite comparisons with many of her contemporaries, including William Merritt Chase, James McNeill Whistler, John Singer Sargent, and Mary Cassatt.

The sitter’s white dress, for instance, evokes Whistler’s infamous 1862 painting of Joanna Hiffernan, Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl (National Gallery of Art, Washington). The formal connection between the two paintings demonstrates Beaux’s knowledge of Whistler’s painting. Additionally, the direct gaze of the black cat perched on Sarah’s shoulder references Edouard Manet’s painting Olympia (1865, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), in which a similarly posed black cat sits at the foot of Olympia’s bed. These connections suggest that Beaux intended to reveal more with this portrait than simply her mastery of painting technique. The enigmatic title of the painting may represent Manet’s influence—Beaux’s use of Spanish diminutives, Sarita for Sarah and Sita, meaning “little one,” for the cat, acknowledges the late 19th-century popularity of Spanish painting, championed by Manet.

The present work is a replica of the original painted in 1893 and displayed in the 1895 Society of American Artists exhibition in New York. Before donating the original to the Musée de Luxembourg in Paris (now in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris), Beaux recorded that she made a second painting for her “own satisfaction when the original went to France for good.” / quoted from NGA

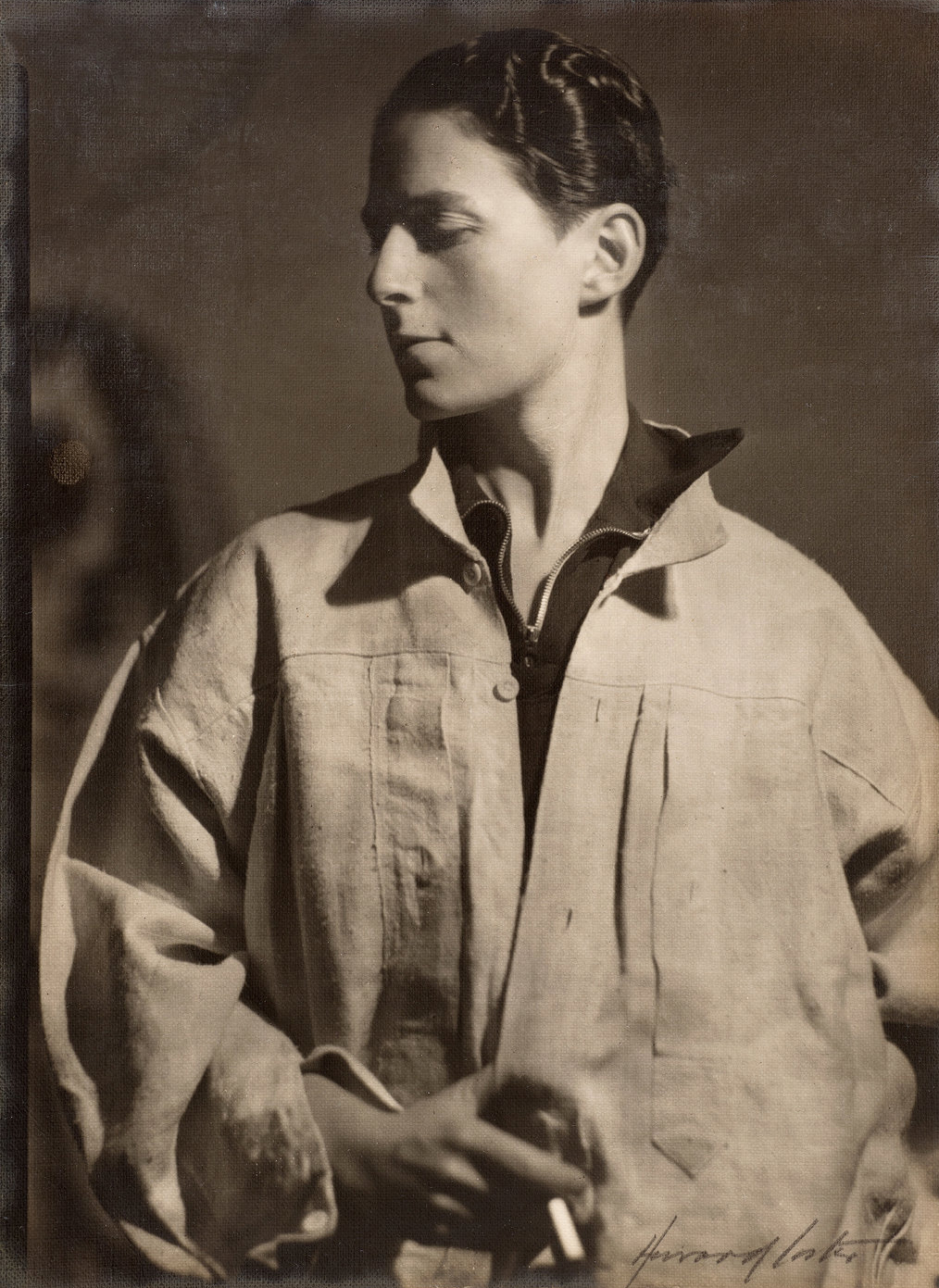

Peter depicts British painter Hannah Gluckstein, heir to a catering empire who adopted the genderless professional name Gluck in the early 1920s. By the time Brooks met her at one of Natalie Barney’s literary salons, Gluckstein had begun using the name Peyter (Peter) Gluck. She unapologetically wore men’s suits and fedoras, clearly asserting the association between androgyny and lesbian identity. Brooks’s carefully nuanced palette and quiet, empty space produced an image of refined and austere modernity. ~ The Art of Romaine Brooks, 2016

Quoted from : Smithsonian American Art Museum (x)

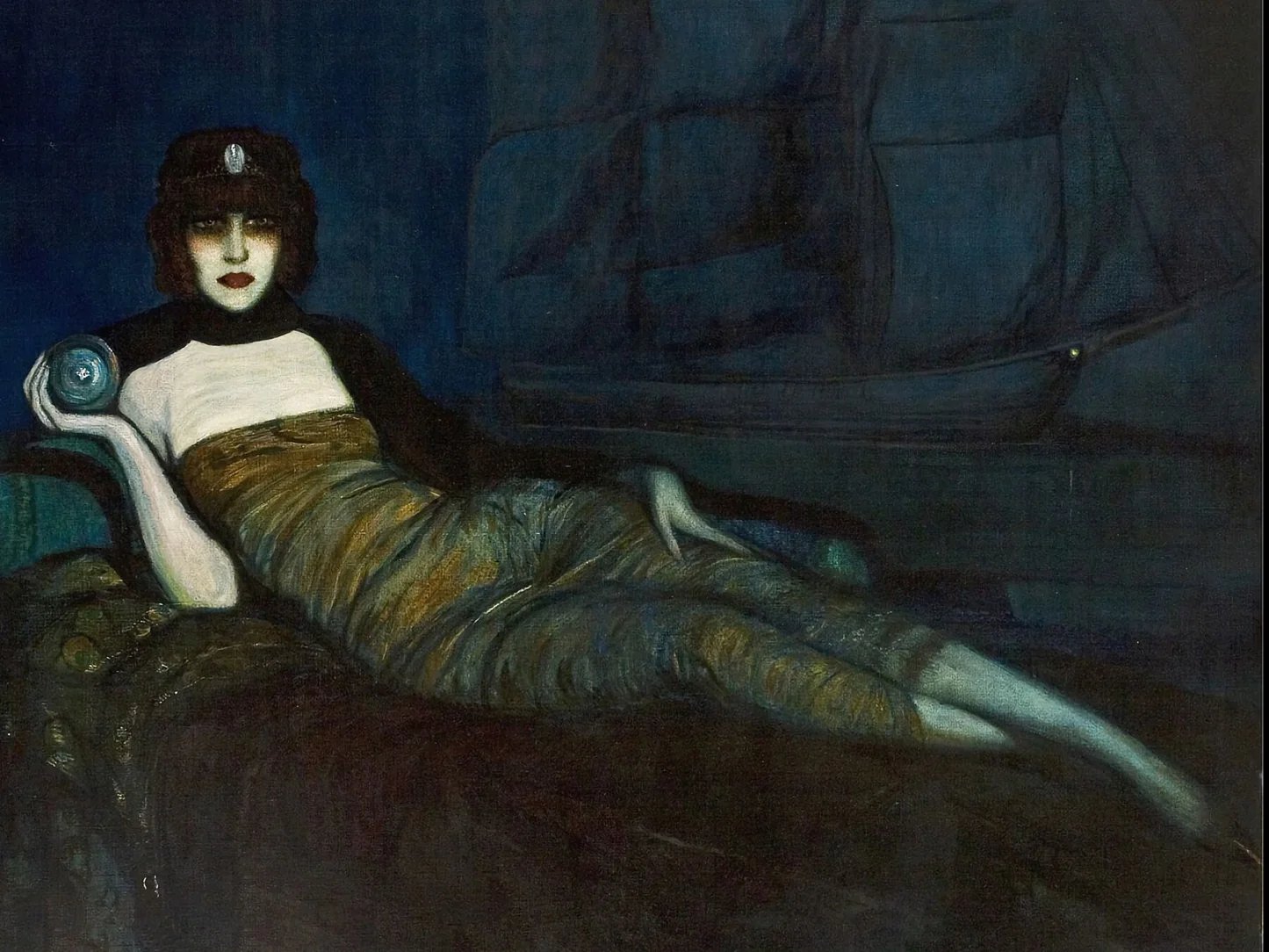

In the last years of his life, Janis Rozentāls repeatedly returned to the composition with the figures of a princess and monkey. The first of the painting was exhibited in 1913 at the 3rd Baltic Artists Union exhibition and at the international art show in Munich where the Leipzig publisher Velhagen & Klasing acquired reproduction rights ensuring wide popularity for the work. The symbolic content of the decoratively resplendent Art Nouveau composition has been interpreted as an allegory of the relationship between artist and society reflecting the power of money over the artist; on other occasions, the princess is seen as “great, beautiful art” but the monkey as the artist bound by golden chains – its servant and plaything. [quoted from Latvijas Nacionālā bibliotēka (link)]

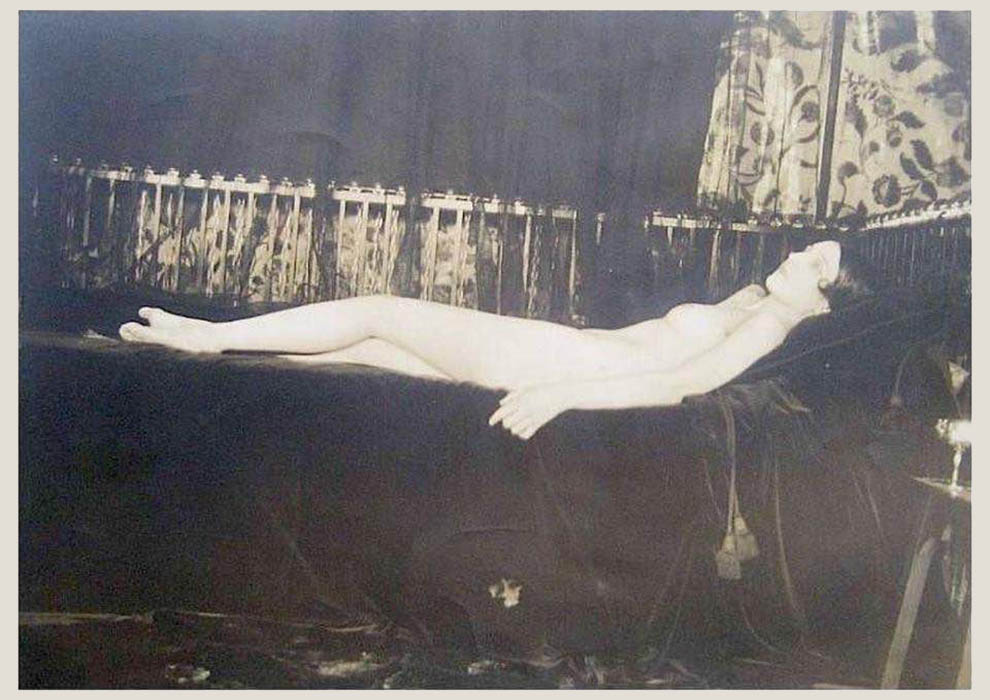

Brooks painted Ida Rubinstein more often than any other subject; for Brooks, Rubinstein’s “fragile and androgynous beauty” represented an aesthetic ideal. The earliest of these paintings are a series of allegorical nudes. In The Crossing (also exhibited as The Dead Woman), Rubinstein appears to be in a coma, stretched out on a white bed or bier against a black void variously interpreted as death or floating in spent sexual satisfaction on Brooks’ symbolic wing. (x)

In 1910, Brooks had her first solo show at the Gallery Durand-Ruel, displaying thirteen paintings, almost all of women or young girls. Among them, Brooks included two nude studies: The Red Jacket, and White Azaleas, a nude study of a woman reclining on a couch. Contemporary reviews compared it to Francisco de Goya’s La maja desnuda and Édouard Manet’s Olympia. But, unlike the women in those paintings, the subject of White Azaleas looks away from the viewer; in the background above her is a series of Japanese prints. (x)

Romaine Brooks remained aloof from all artistic trends, painting, in her palette of black, white, and grays, haunting portraits of the blessed and the troubled, of socialites and intellectuals. She moved in brilliant circles and, while resisting companionship, was the object of violent passions. […] Her story and her work reveal much about bohemian life in the early twentieth century.

Elizabeth Chew Women Artists at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (x)

Describing herself as a lapidée (literally: a victim of stoning, an outsider), at the height of her career Brooks was prominent in the intellectual and cosmopolitan community that moved between Capri, Paris and London in the early 1900s. Brook’s best known images depict androgynous women in desolate landscapes or monochromatic interiors, their protagonists undeterred by our presence, either staring relentlessly at us or gazing nonchalantly past. Her subjects of this time include anonymous models, aristocrats, lovers and friends, all portrayed in her signature ashen palette. Rejecting contemporary artistic trends such as cubism and fauvism, Brooks favoured the symbolist and aesthetic movements of the 19th century, particularly the work of James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Her ability to capture the expression, glance or gaze of her sitters prompted critic Robert de Montesquiou to describe her, in 1912, as ‘the thief of souls’. quoted from Frieze

Peter depicts British painter Hannah Gluckstein, heir to a catering empire who adopted the genderless professional name Gluck in the early 1920s. By the time Brooks met her at one of Natalie Barney’s literary salons, Gluckstein had begun using the name Peyter (Peter) Gluck. She unapologetically wore men’s suits and fedoras, clearly asserting the association between androgyny and lesbian identity. Brooks’s carefully nuanced palette and quiet, empty space produced an image of refined and austere modernity. ~ The Art of Romaine Brooks, 2016

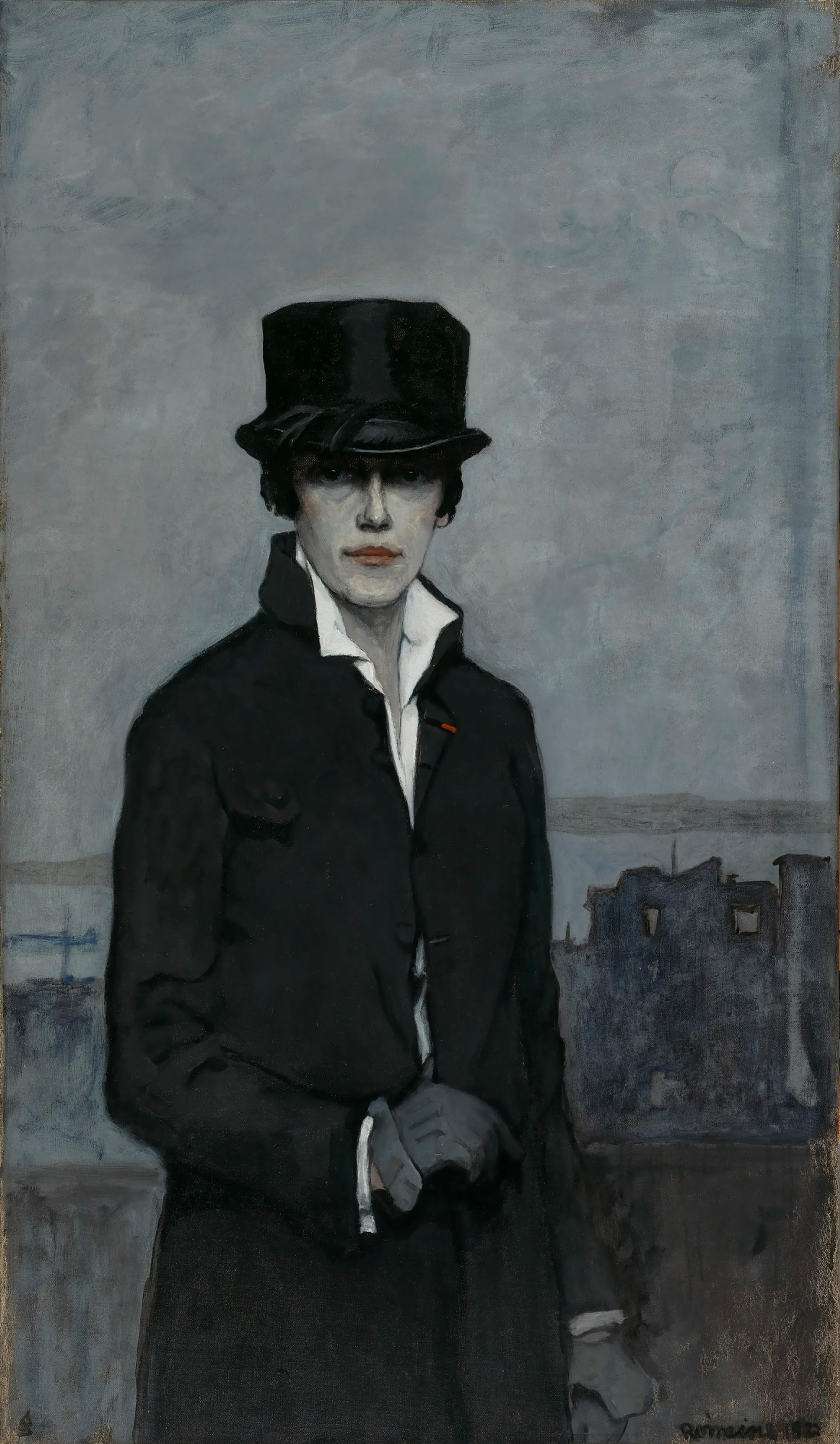

With this self-portrait, Brooks envisioned her modernity as an artist and a person. The modulated shades of gray, stylized forms, and psychological gravity exemplify her deep commitment to aesthetic principles. The shaded, direct gaze conveys a commanding and confident presence, an attitude more typically associated with her male counterparts. The riding hat and coat and masculine tailoring recall conventions of aristocratic portraiture while also evoking a chic androgyny associated with the post–World War I “new woman.” Brooks’s fashion choices also enabled upper-class lesbians to identify and acknowledge one another. ~ The Art of Romaine Brooks, 2016

Una Troubridge was a British aristocrat, literary translator, and the lover of Radclyffe Hall, author of the 1928 pathbreaking lesbian novel, The Well of Loneliness. Troubridge appears with a sense of formality and importance typical of upper-class portraiture, but with the sitter’s prized dachshunds in place of the traditional hunting dog. Troubridge’s impeccably tailored clothing, cravat, and bobbed hair convey the fashionable and daring androgyny associated with the so-called new woman. Her monocle suggested multiple symbolic associations to contemporary British audiences: it alluded to Troubridge’s upper-class status, her Englishness, her sense of rebellion, and possibly her lesbian identity. ~ The Art of Romaine Brooks, 2016

In La France Croisée, Brooks voiced her opposition to World War I and raised money for the Red Cross and French relief organizations. Ida Rubinstein was the model for this heroic figure posed in a nurse’s uniform, with cross emblazoned against her dark cloak, against a windswept landscape outside the burning city of Ypres. This symbolic portrait of a valiant France was exhibited in 1915 at the Bernheim Gallery in Paris, along with four accompanying sonnets written by Gabriele D’Annunzio. The gallery offered reproductions for sale as a benefit to the Red Cross. For her contributions to the war effort, the French government awarded Brooks the Cross of the Legion of Honor in 1920. This award is visible as the bright red spot on Brooks’s lapel in her 1923 Self-Portrait. ~ The Art of Romaine Brooks, 2016

Brooks met Russian dancer and arts patron Ida Rubinstein in Paris after Rubinstein’s first performance as the title character in Gabriele D’Annunzio’s play The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian. Rubinstein was already well known for her refined beauty and expressive gestures; she secured her reputation as a daring performer by starring as the male saint in this boundary-pushing show that combined religious history, androgyny, and erotic narrative. Brooks found her ideal — and her artistic inspiration — in the tall, lithe, sensuous Rubinstein, who modeled for many sketches, paintings, and photographs Brooks produced during their relationship, from 1911 to 1914. In her autobiographical manuscript, “No Pleasant Memories,” Brooks said the inspiration for this portrait came as the two women walked through the Bois de Boulogne on a cold winter morning. ~ The Art of Romaine Brooks, 2016

All quotations and images (except n. 1 & 2) are from the Smithsonian American Art Museum (x)

Although not recorded in Simon Toll’s catalogue raisonné on Draper, the present lot can probably be dated to 1892-93, when the artist was working in Rome. There are a number of related studies for the work, one of which, entitled ‘Pompilia’, depicts a girl in a similar crocheted cap (illustrated p.79, no. 33). The work can also be compared with other paintings of this period, such as ‘Love in the Garden of Philetas’ (RA 1892) and ‘The Spirit of the Fountain’ (1893), where flowers and ornamental gardens appear as popular motifs. | quoted from Bonhams London