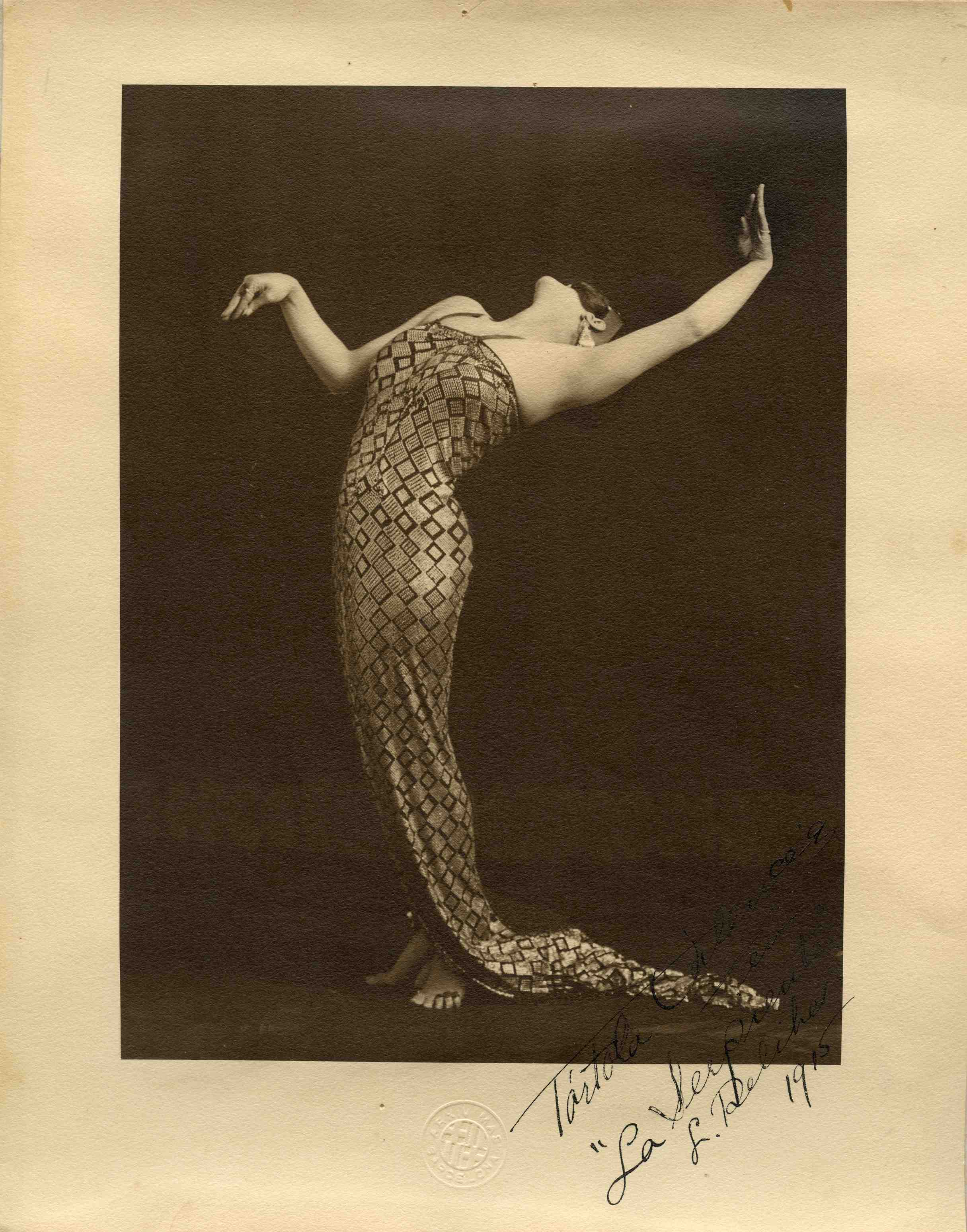

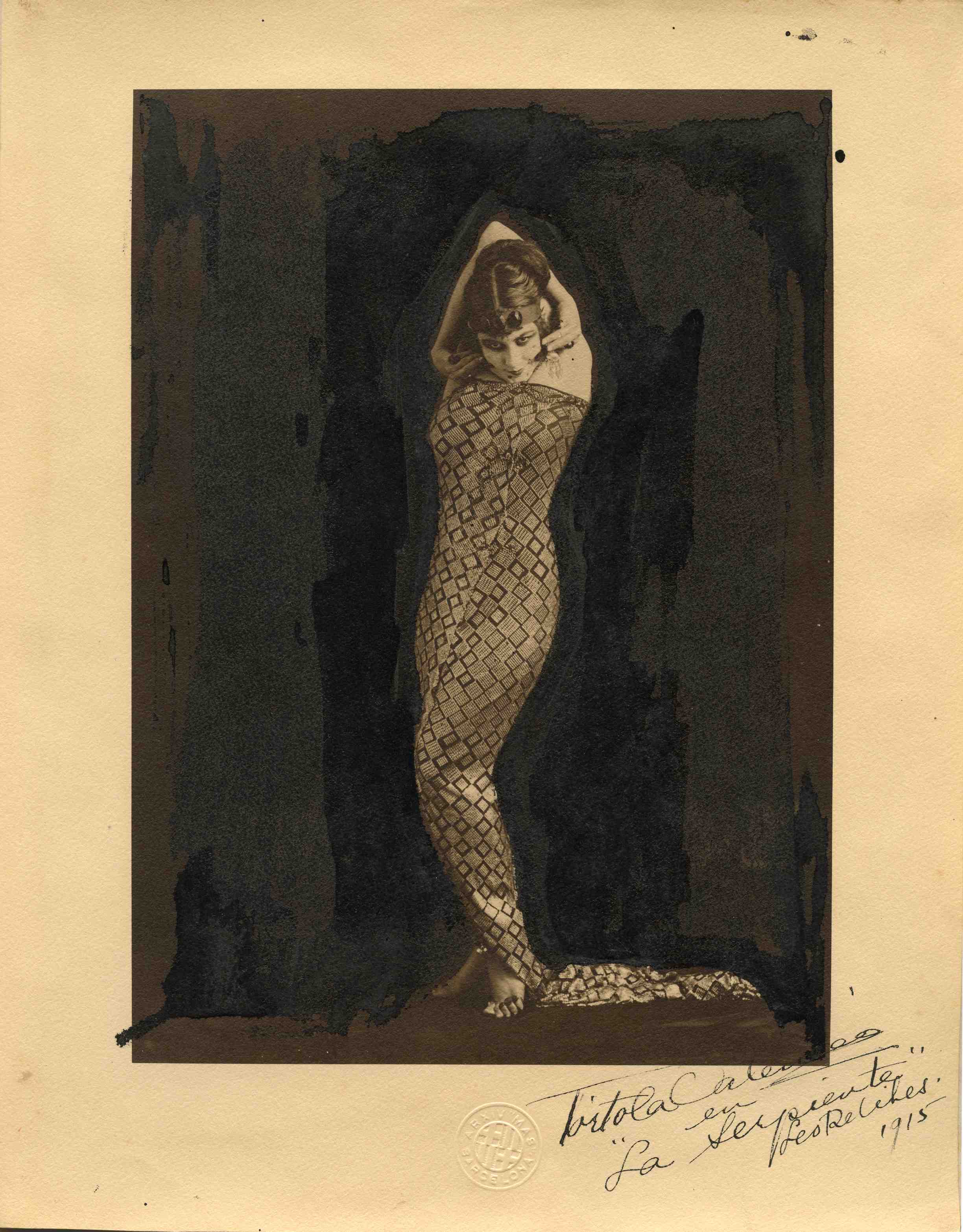

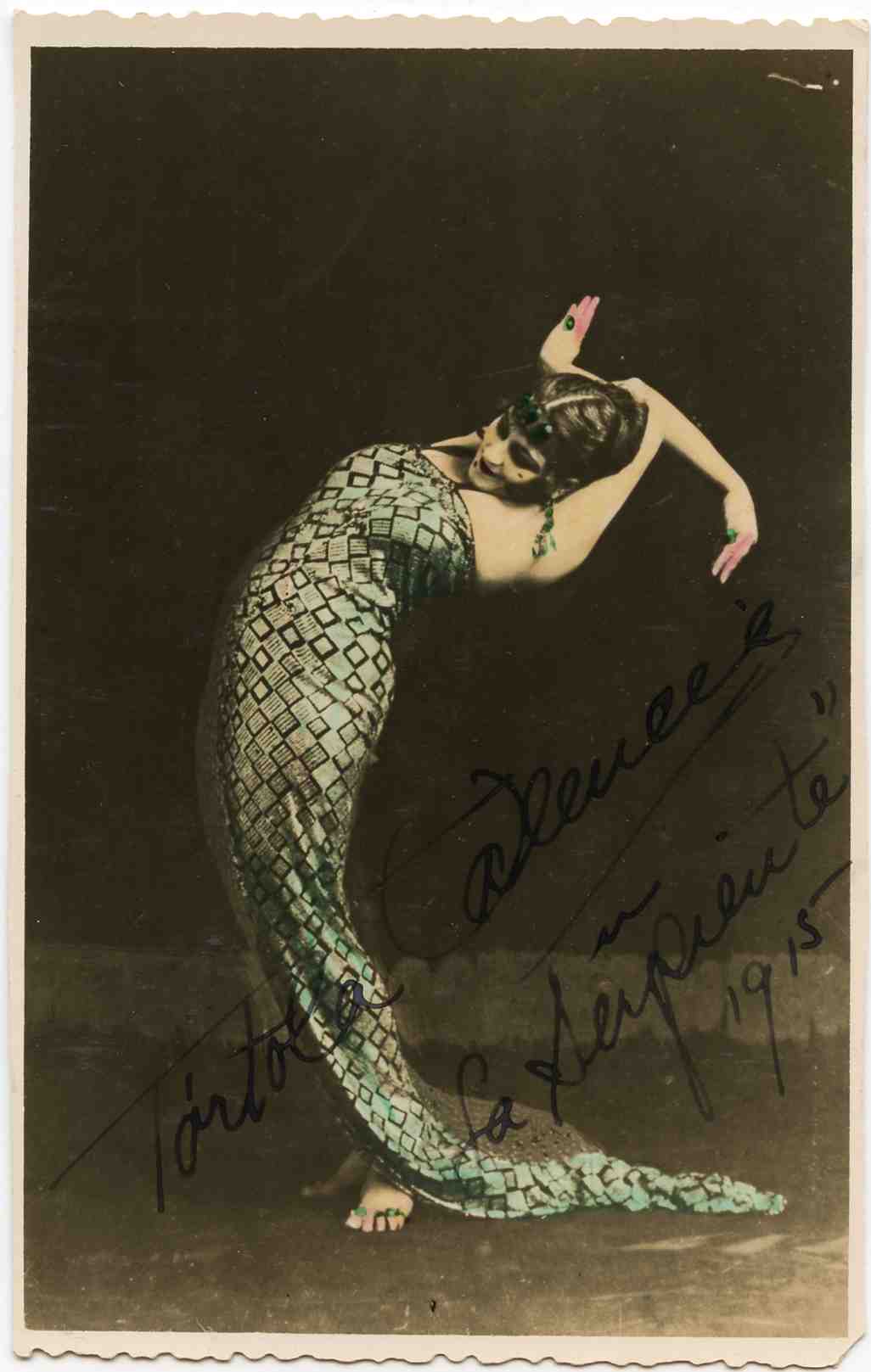

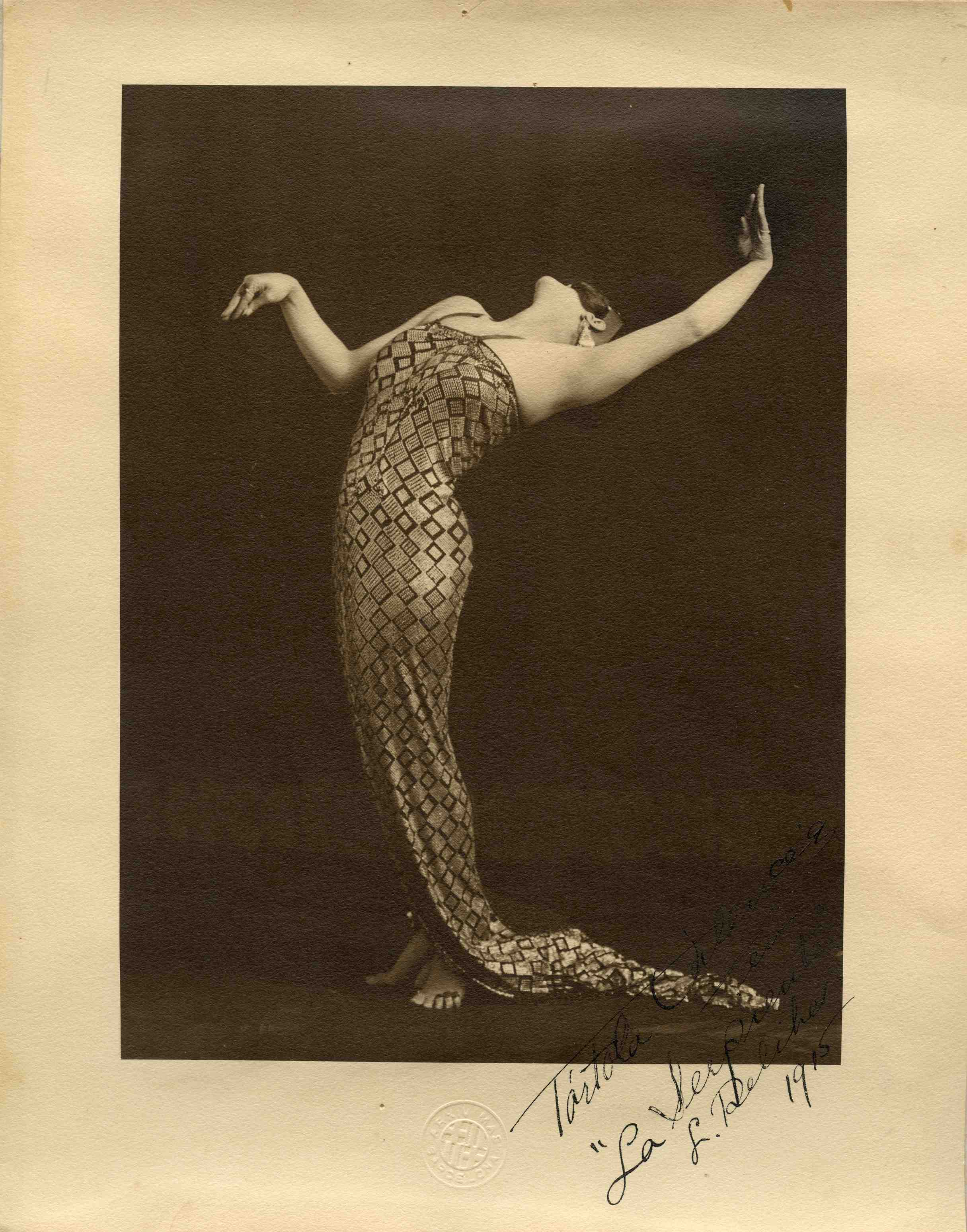

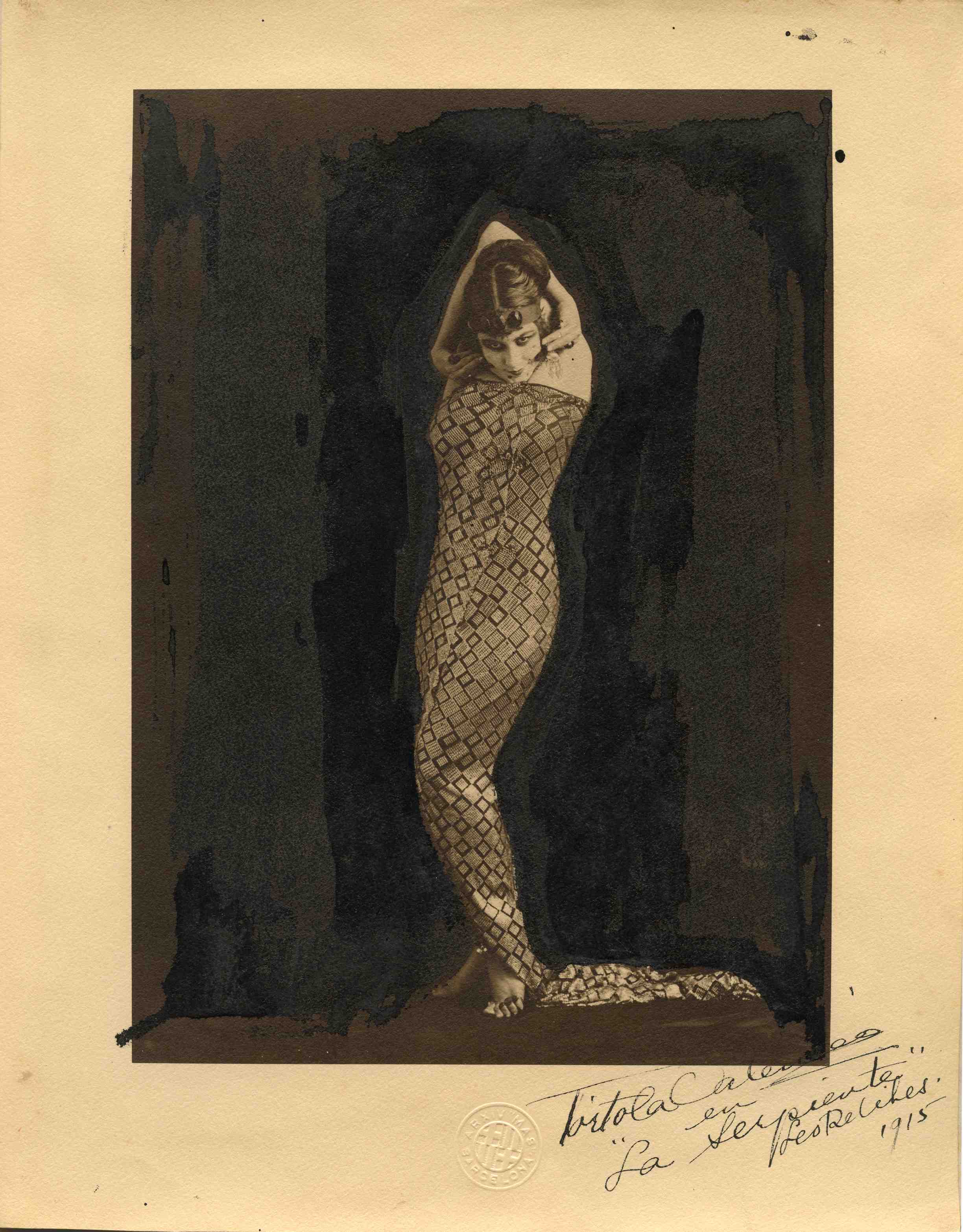

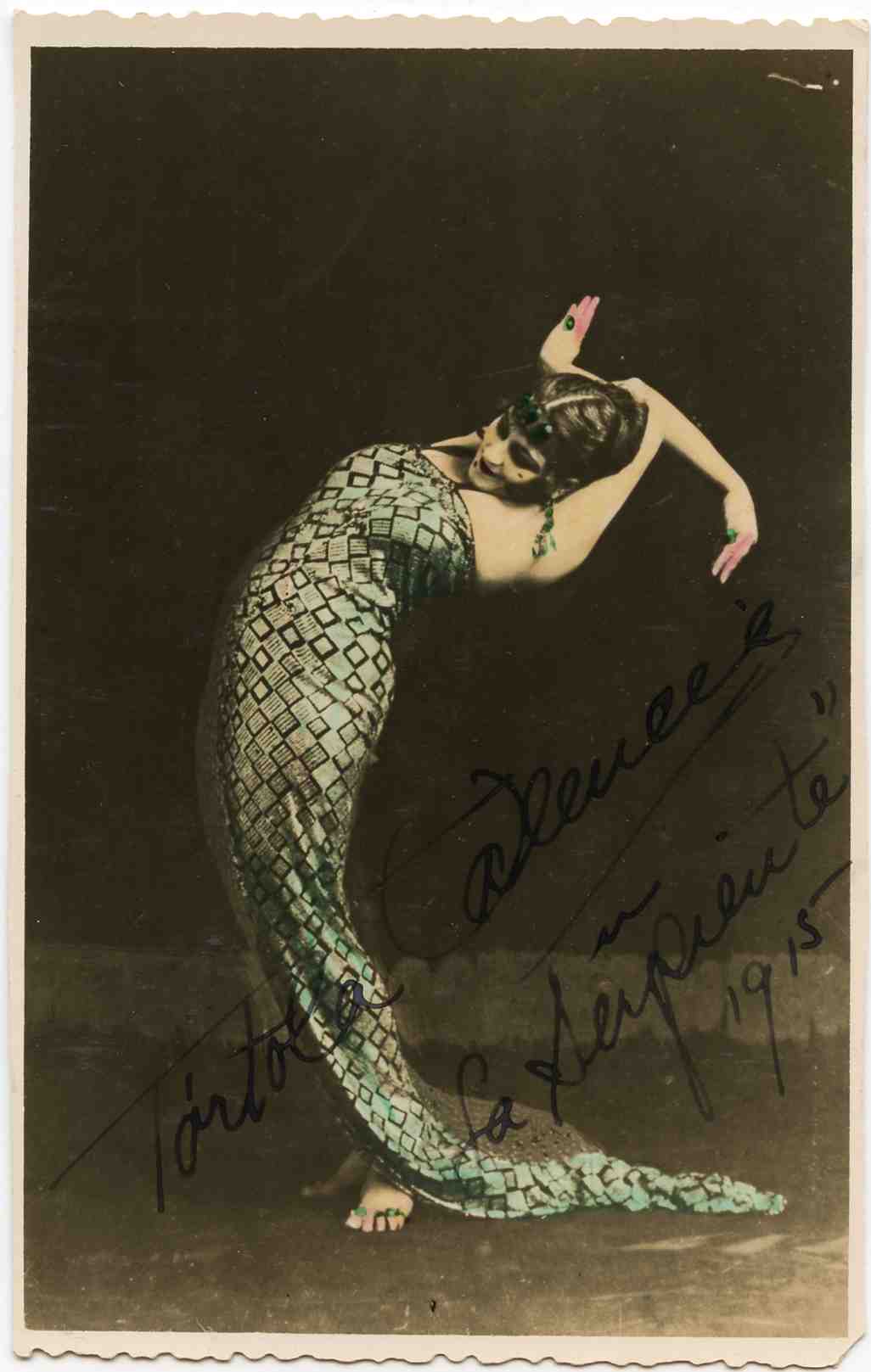

All images retrieved from Centre de Documentació i Museu de les Arts Escèniques (cdmae) / Arxiu Tórtola Valencia

images that haunt us

All images retrieved from Centre de Documentació i Museu de les Arts Escèniques (cdmae) / Arxiu Tórtola Valencia

El escritor Luis Antonio de Villena fue el recuperador de la figura de Tórtola en los artículos y prólogos que dedicó desde 1975 al novelista decadente Antonio de Hoyos y Vinent (éste fue uno de los tres hombres con los que se relacionó amorosamente a Tórtola)—los otros fueron el rey Alfonso XIII y el archiduque José de Baviera—. Con Antonio, Carmen solo compartió una densa amistad que les sirvió para ocultar sus verdaderas preferencias amorosas. Estos célebres nombres alimentaban el universo de Carmen que ella misma aderezaba a su antojo. Cuenta De Villena que cuando estrenó la llamada Danza incaica —inventada por ella misma— con un vestido lleno de tubitos color hueso, dijo que era un vestido hecho con huesos de los conquistadores. Nadie lo creía pero quedaba muy bien. Sin duda, la leyenda es parte de la creación del artista y en el periodo simbolista de entresiglos se dio abundantemente.

quoted from Jot down : Tórtola Valencia: entre la danza y el deseo

All images retrieved from Centre de Documentació i Museu de les Arts Escèniques (cdmae) / Arxiu Tórtola Valencia

Carmen Tórtola Valencia (Sevilla, 18 de junio de 1882 – Barcelona, 13 de febrero de 1955)

De padre catalán (Florenç Tórtola Ferrer) y madre andaluza (Georgina Valencia Valenzuela), cuando tenía tres años su familia emigró a Londres. Sus padres murieron en Oaxaca (México) en 1891 y 1894 respectivamente. Se ha especulado mucho sobre su misterioso origen; según algunos era una bastarda de la familia real española, según otros era hija de un noble inglés. En su libro Tórtola Valencia and Her Times (1982), Odelot Sobrac, uno de sus primeros biógrafos, afirma que desarrolló un estilo propio que expresaba la emoción con el movimiento y se inspiró al parecer en Isadora Duncan.

Especialista en danzas orientales, se interesó sobre todo por las danzas africanas, árabes e indias, que reinterpretó a su modo, investigando en todo tipo de bibliotecas; en cierto sentido llevó la antropología a la danza; su versatilidad como bailarina quedó sin embargo probada a lo largo de su vida. Su fama trascendió los límites profesionales a causa de sus innumerables amantes (gobernantes y escritores de renombre), por su belleza andaluza de ojos negros (fue considerada una de las mujeres más bellas de Europa) y por sus extensos conocimientos fruto de sus numerosos viajes y su pasión por la vida. Su primera aparición pública fue en 1908 en el Gaity Theatre de Londres como parte del espectáculo Habana.

Ese mismo año fue invitada a bailar en el Wintergarten y en el Folies Bergère. Allí fue denominada «La Bella Valencia», una nueva favorita del público como La Bella Otero o Raquel Meller. Al año siguiente bailó en Nürenberg y Londres. Fue invitada a unirse al Cirkus Varieté de Copenhague con Alice Réjane. Estuvo en Grecia, Rusia e India. Su debut español fue en 1911 en el Teatro Romea en Madrid. Volvió al mismo teatro en 1912. Fue nombrada en 1912 socia de honor y profesora estética del Gran Teatro de Arte de Múnich. En 1913 hizo una gira por España que incluyó el Ateneo de Madrid. En 1915 actuó con Raquel Meller en Barcelona.

En 1916, Tórtola fue caricaturizada en la revista de humor catalana Papitu como otra Mata Hari. Fue sin embargo su arte más bien apreciado por los intelectuales que por la gran masa del público. Emilia Pardo Bazán dijo de ella que era la personificación del Oriente y la reencarnación de Salomé. Tórtola fue una artista ecléctica y polifacética. En 1915 actuó en los filmes Pasionaria y Pacto de lágrimas, dirigidos por Joan Maria Codina. Viajó a Nueva York para actuar en el Century Theatre.

En 1920 la Galería Laietana de Barcelona exhibió 45 de sus pinturas sobre danza. Al año siguiente marchó de gira por Hispanoamérica. Entre 1921 y 1930 alcanzó allí una gran popularidad.

Fue una gran aficionada al arte precolombino, llegando a constituir una excelente colección de piezas procedentes de las más variadas civilizaciones del continente americano, especialmente de México y Perú.

Su independencia y vida desenvuelta fue sentida como una amenaza para los valores tradicionales de la sociedad española. Fue una pionera de la liberación de la mujer, como Isadora Duncan, Virginia Woolf y Sarah Bernhardt. Era budista y vegetariana, fue morfinómana y abogó por la abolición del corsé que impedía el libre movimiento femenino. Aunque tuvo numerosos amantes masculinos, sobre todo intelectuales, vivió la mayor parte de su vida con una mujer, Ángeles Magret Vilá, a la que adoptó como hija para guardar las apariencias. Quizá por ello defendió a capa y espada su intimidad y se destila de sus orígenes cierto misterio. Abandonó la danza el 23 de noviembre de 1930 en Guayaquil (Ecuador).

En 1931 se declaró republicana catalana y marchó a Barcelona con Ángeles. Dedicó los últimos años de su vida a coleccionar grabados y estampas y se inició en el budismo. Murió el 15 de marzo de 1955 en su casa del barrio de Sarriá en Barcelona. Creó la Danza del incienso, La bayadera, Danza africana, Danza de la serpiente y Danza árabe. Aparece como personaje en la novela Divino de Luis Antonio de Villena, y Ramón López Velarde le dedicó el poema Fábula dística. Prestó su imagen para el perfume “Maja” de la conocida casa de cosméticos Myrurgia.

Su contribución al arte de la danza consistió en una sensibilidad y orientación estética que ponían de manifiesto la sensualidad del cuerpo. La danza moderna, calificada entonces de irreverente por natural, respondía a sus ideales modernistas empapados de filosofías orientales.

El fondo de partituras de Tórtola Valencia se conserva en la Biblioteca de Cataluña. El resto, que incluye 112 piezas de indumentaria y complementos, 246 cuadros y dibujos, casi 1500 fotografías y carpetas de gran formato con carteles, fotografías, recortes e impresos y testigos de su vida artística y social se conserva en el Museo de las Artes Escénicas (MAE) del Instituto del Teatro de Barcelona. El MAE conserva además algunas tarjetas postales, programas de mano y 2 volúmenes de epistolario con el título genérico de “Los poetas a Tórtola Valencia”.

quoted from the wikipedia entry (in Spanish)

Marie Haushofer presented roles that women had played in different eras and centuries. At the same time, she also traced the path of women in their cultural-historical development – from servitude and lack of culture, interrupted by a brief flash of female domination in the kingdom of the Amazons […] Read more below

Evas Töchter. Münchner Schriftstellerinnen und die moderne Frauenbewegung 1894-1933

Eve’s daughters. Munich women writers and the modern women’s movement 1894-1933

Around 1900 profound changes took place in all areas of life. There is a new beginning everywhere, in the circles of art, literature, music and architecture. The naturalists are the first to search for new possibilities of representation. They are followed by other groups and currents: impressionism, art nouveau, neo-classical, neo-romantic and symbolism. Even if this epoch does not form a unit, one guiding principle runs through all styles: the awareness of a profound turning point in time.

It is generally known that before the turn of the century Munich became one of the most important cultural and artistic sites in Europe. What is less well known is that Munich has also become a center of the bourgeois women’s movement in Bavaria since the end of the 19th century. At this time, a lively scene of the women’s movement formed in the residence city, which subsequently gained great influence on the bourgeoisie throughout Bavaria.

Since 1894, Munich has been shaped by the modern women’s movement, which advocates the right to education and employment for women. At that time, the city was decisively shaped by women such as Anita Augspurg, Sophia Goudstikker, Ika Freudenberg, Emma Merk, Marie and Martha Haushofer, Carry Brachvogel, Helene Böhlau, Gabriele Reuter, Helene Raff, Emmy von Egidy, Maria Janitschek and many other women’s rights activists and writers and artists, all of whom are members of the Association for Women’s Interests, which is largely responsible for the spread of the modern women’s movement in Bavaria. At that time, they all set out in search of a new self-image for women, questioned the traditional role models in the bourgeoisie and attempted to redefine gender roles.

In this context, on October 1899 the First Bavarian Women’s day was celebrated. The crowning glory of the First General Bavarian Women’s Day in 1899 was a festive evening that took place on October 21, 1899 in the large hall of the then well-known Catholic Casino at Barer Straße 7.

The first part of the festive evening was the performance of an impressive festival play: Cultural images from women’s lives. Twelve group representations [„Zwölf Culturbilder aus dem Leben der Frau“]. The piece was written by the painter a poet Marie Haushofer (1871-1940) especially for this occasion. Sophia Goudstikker directed it and she also played a part. The majority of the roles were played by many other protagonists of the Munich women’s movement. A few days later, Sophia Goudstikker photographed the twelve group portraits in the Elvira photo studio (Atelier Elvira). She glued the photographs into a leather album entitled Marie Haushofer’s festival for the first general Bavarian women’s day in Munich. October 18-21, 1899 [Marie Haushofers Festspiel zum Ersten allgemeinen Bayrischen Frauentag in München, 18. – 21. Oktober 1899]. Those are the 13 surviving scene photos (group portraits) that documented the event; today they are part of the Munich City Archive (Stadtarchiv München).

In her festival play, Marie Haushofer presented roles that women had played in different eras and centuries. At the same time, she also traced the path of women in their cultural-historical development – from servitude and lack of culture, interrupted by a brief flash of female domination in the kingdom of the Amazons, to burgeoning knowledge, to work, freedom and finally the union of women who from then on did their work – but also have to assert powerfully achieved new social status through unity. The present represents the last group in which “modern women” appear in “modern professions”: telephone operators, bookkeepers, scholars, painters, etc. They are accompanied by the allegorical figures of Faith, Love, Hope (*) and the Spirit of Work (**) that liberates all women / working women. Finally, the female audience is called upon to work and to actively shape together the present role of women.

[(*) see photo on bottom of this post (last photo) / (**) last-but-one photo]

Further productions took place in Nuremberg in 1900 and on November 28 and 30, 1902 at the Bayreuth Opera.

But the festive evening of Bavarian Women’s Day did not end with the performance of the festival play. In the second part of the evening, “poems of modern women poets” were presented. There were works by Ada Negri, Lou Andreas-Salomé, Alberta von Puttkammer, Anna Ritter, Ricarda Huch and Maria Janitschek. The short prose text Nordic Birch by the Art Nouveau artist and writer Emmy von Egidy was also read.

[adapted text quoted (an translated) from : Evas Töchter : Frauenmut und Frauengeist : Literatur Portal Bayern]