images that haunt us

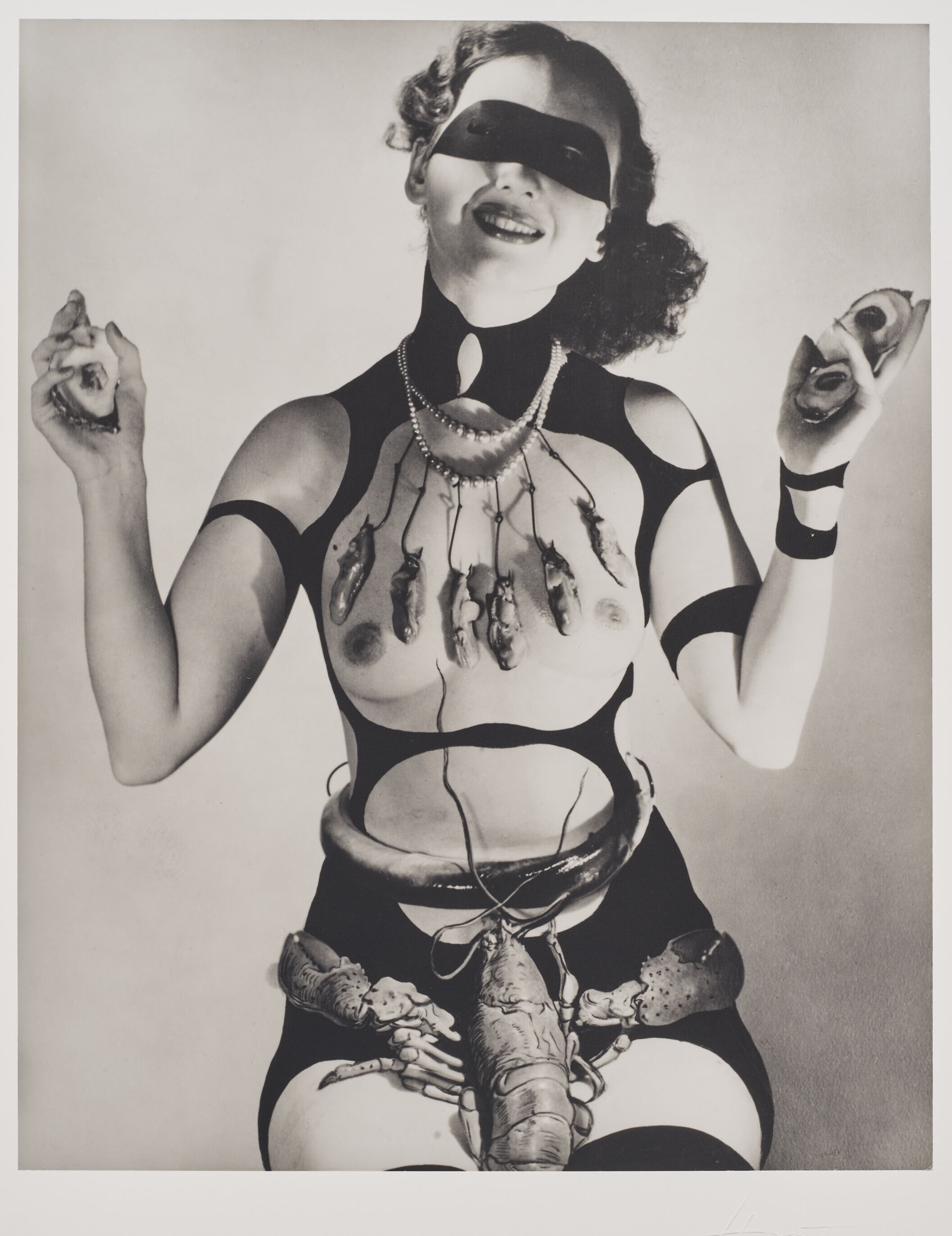

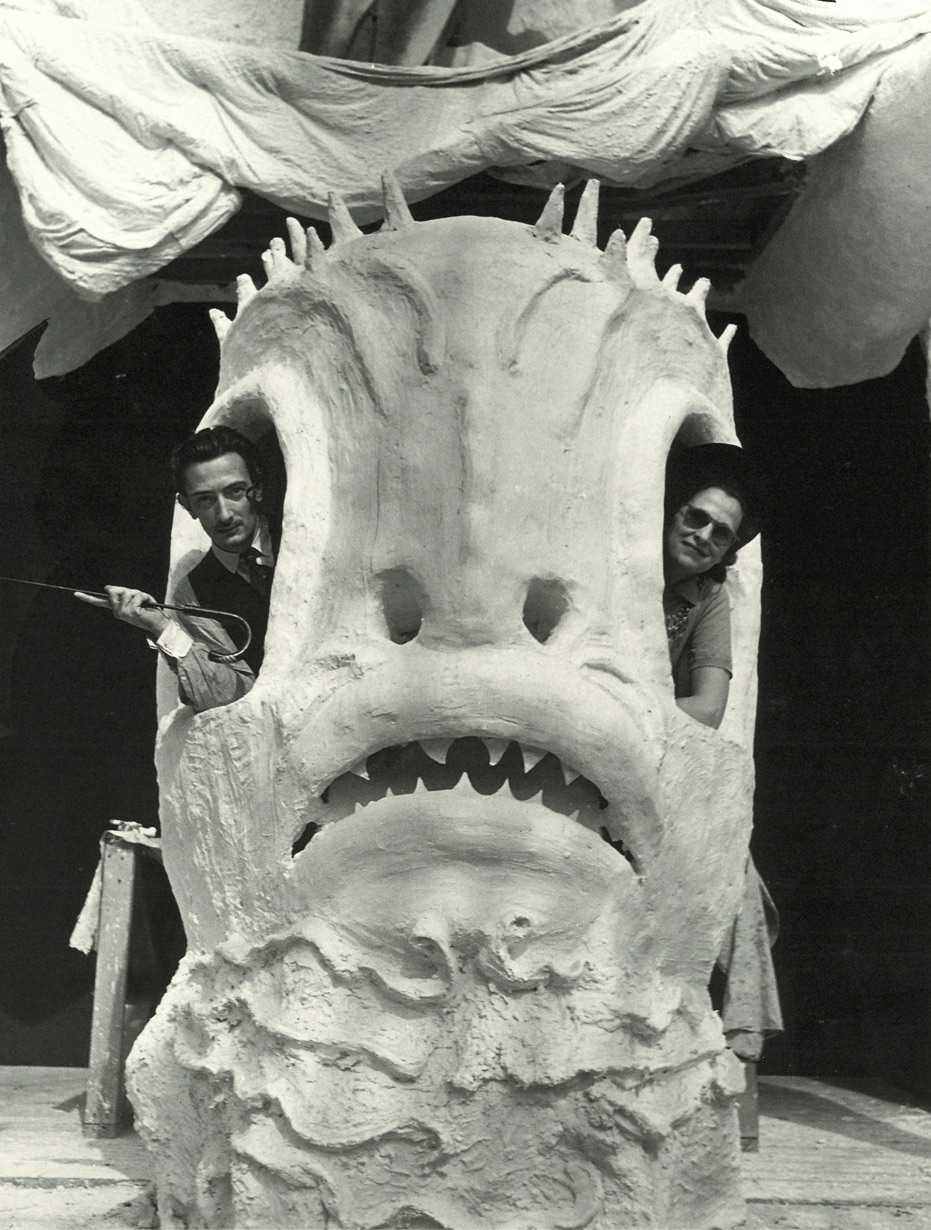

In June 1939 Salvador Dalí designed a pavilion for the New York World’s Fair built by the architect Ian Woodner. The building was named Dream of Venus.

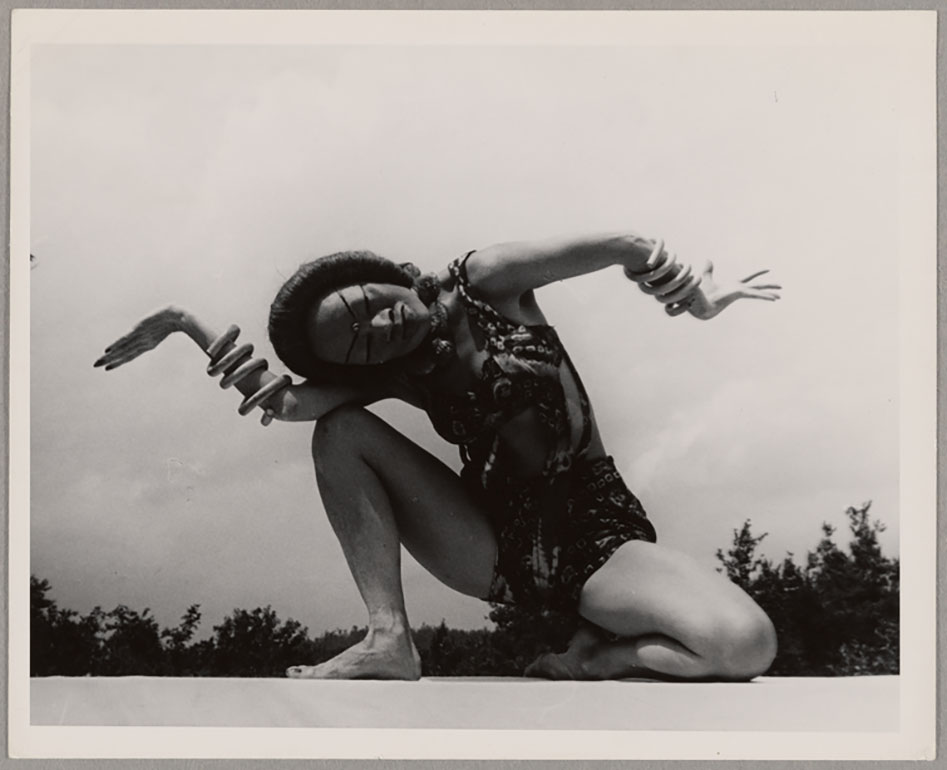

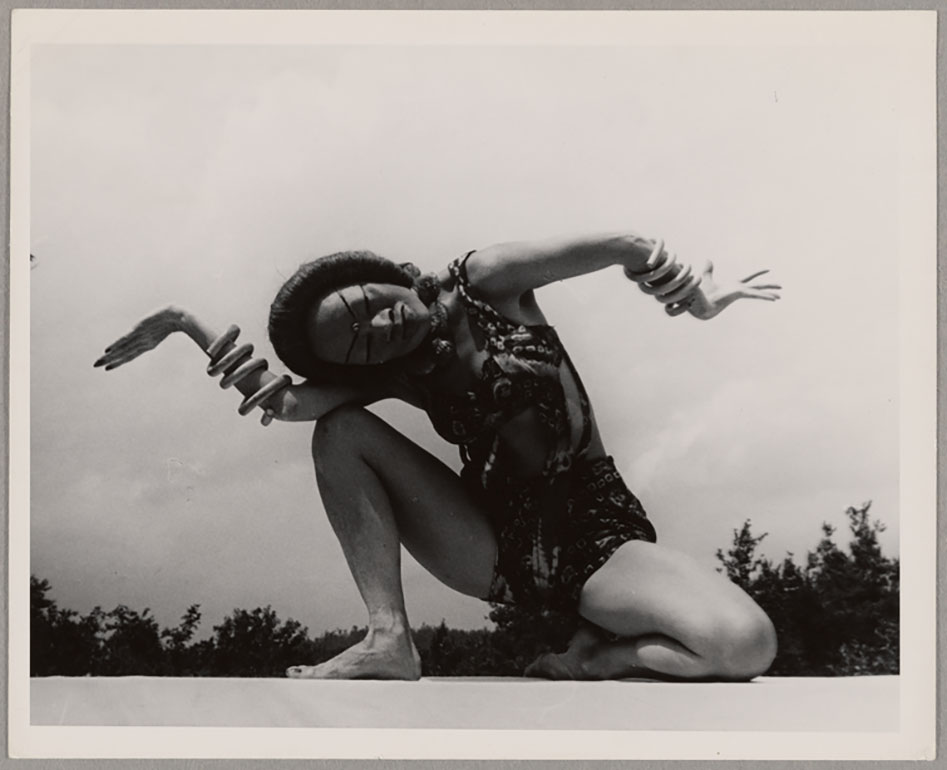

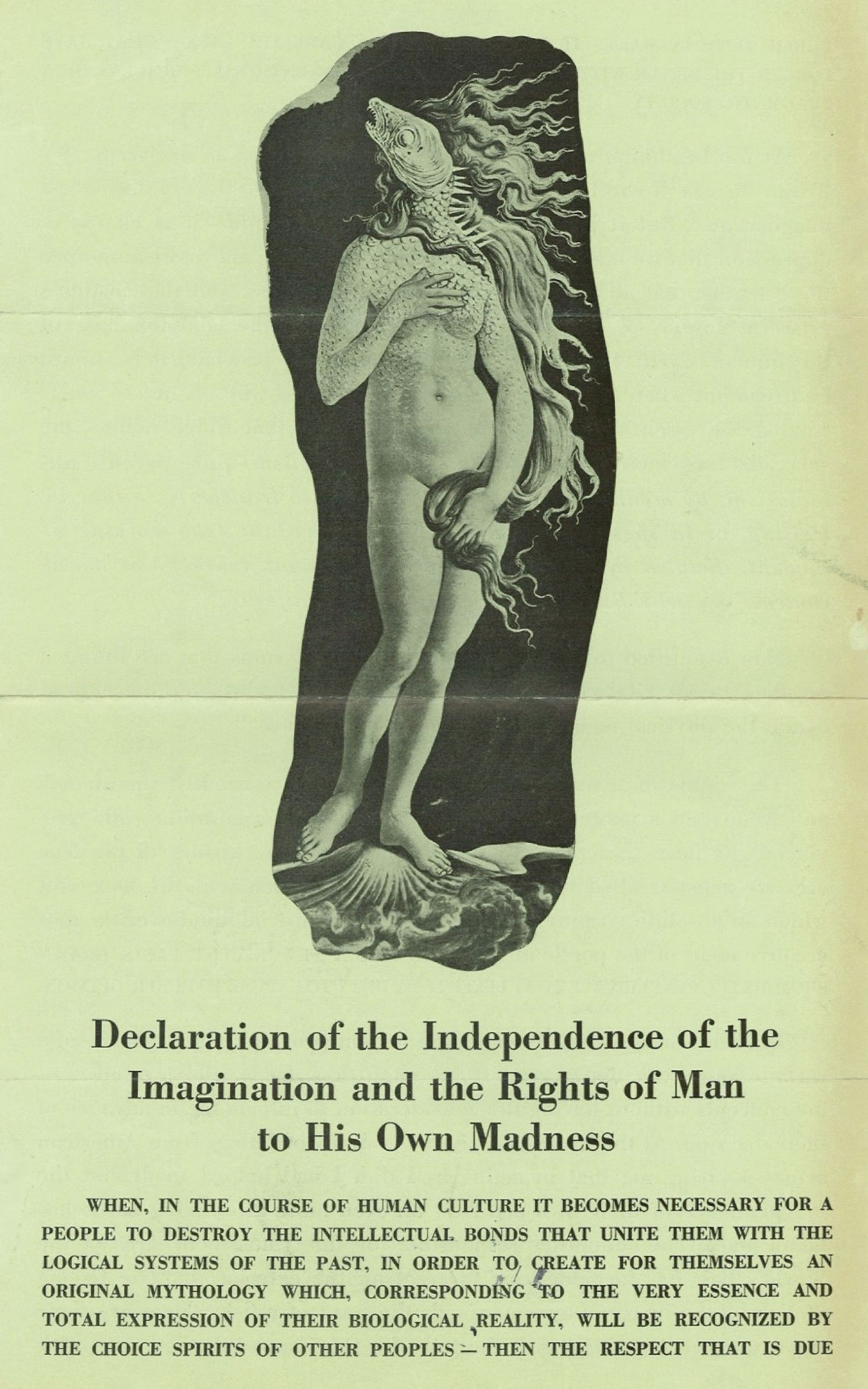

The pavilion featured a spectacular facade full of protuberances, vaguely reminiscent of the Pedrera building by Antoni Gaudí. The main door was flanked by two pillars representing two female legs wearing stockings and high-heeled shoes. Through the openings of the irregular façade, visitors could see reproductions of the Saint John the Baptist by Leonardo da Vinci and The Birth of Venus by Botticelli. The outer part of the building also had crutches, cacti, hedgehogs, etc. Inside, the pavilion offered visitors an aquatic dance show in two large swimming pools, with sirens and other items also designed by Dalí, some of them taking their inspiration from the work of Bracelli. Between the painter’s initial ideas and the final result of the project there arose major modifications, which led Dalí to complain about the Fair’s requirements in a pamphlet entitled Declaration of the Independence of the Imagination and the Rights of Man to His Own Madness. […] [quoted from dali.org]

Salvador Dalí wrote this declaration after his experience creating a pavilion for the 1939 New York World’s fair. The ‘Dream of Venus’ pavilion was a Surrealist undersea grotto where semi naked women performed in tanks playing piano and milking cows amongst other suitably surreal activities. The image on this pamphlet of Botticelli’s Venus with the head of a fish was Dalí’s original idea for the Pavilion’s entrance. However, the design was rejected by the Fair’s organizers who stated “‘A woman with the head of a fish is impossible” and replaced it with a simple reproduction of Venus. Believing that his artistic vision had been unacceptably compromised, Dalí responded by producing this pamphlet berating the Fair’s organizers and rallying against mediocrity in art by consensus. [quoted from V&A museum]

[…] Despite the conflicts that derived from Dalí’s collaboration with the organizers of the Fair, his participation has to be rated as a highly important moment within the painter’s increasing approximation to mass culture, and his need to project his ideas beyond the strict circles of artistic culture. In this sense it may not be exaggerated to state that The Dream of Venus was a first version (though with features and a context of its own) of that other enormous “inhabitable” and “visitable” artistic object that was to be the Dalí Theatre-Museum of Figueres many years later. [quoted from dali.org]

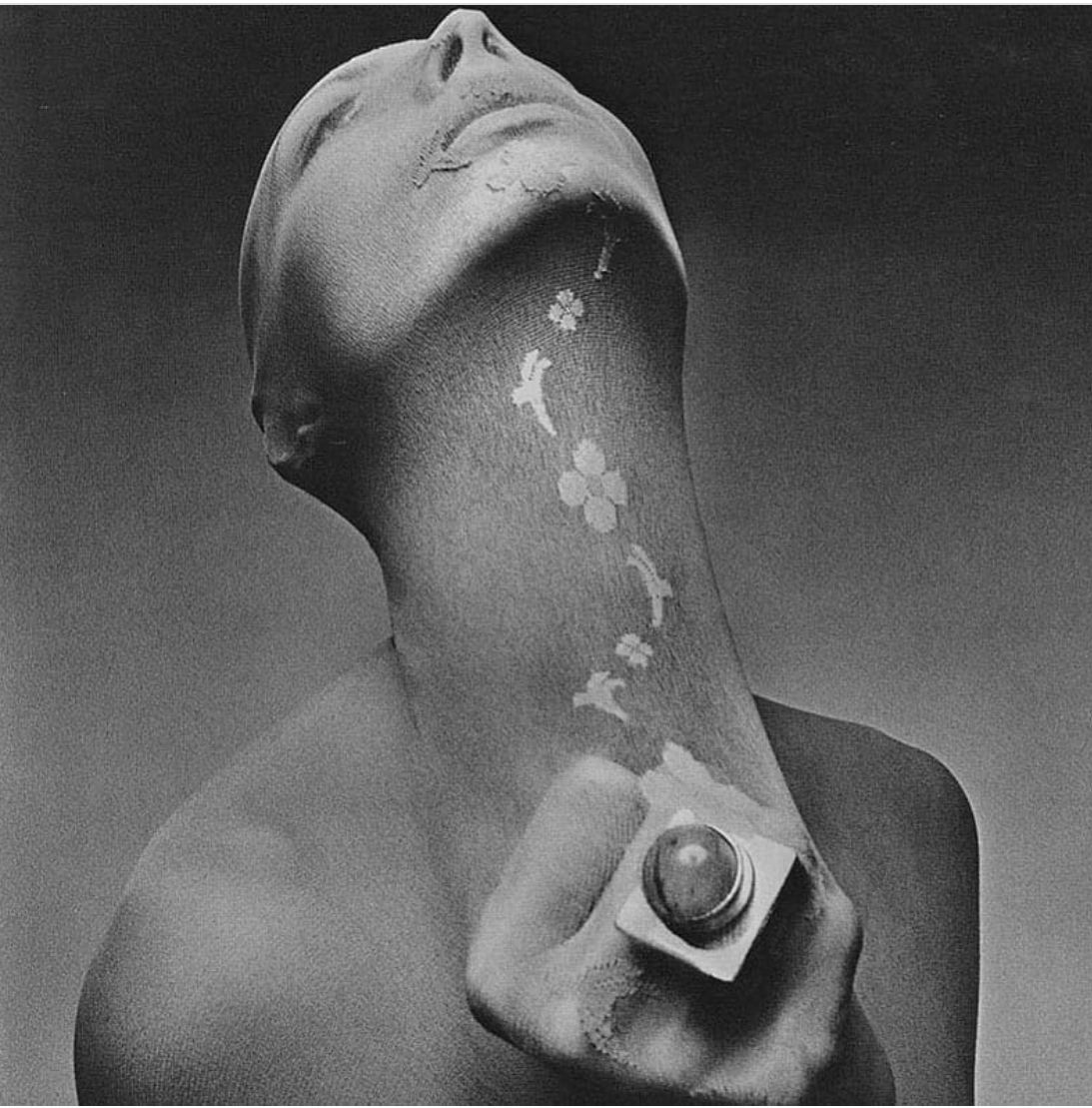

The Mimosa paper label on the verso of the mount indicates that this photo was used as an advertisement to demonstrate Mimosa paper. Mimosa used the negatives of many well-known German photographers such as Hugo Erfurth, d’Ora and Yva to demonstrate the various photo paper qualities the firm produced.

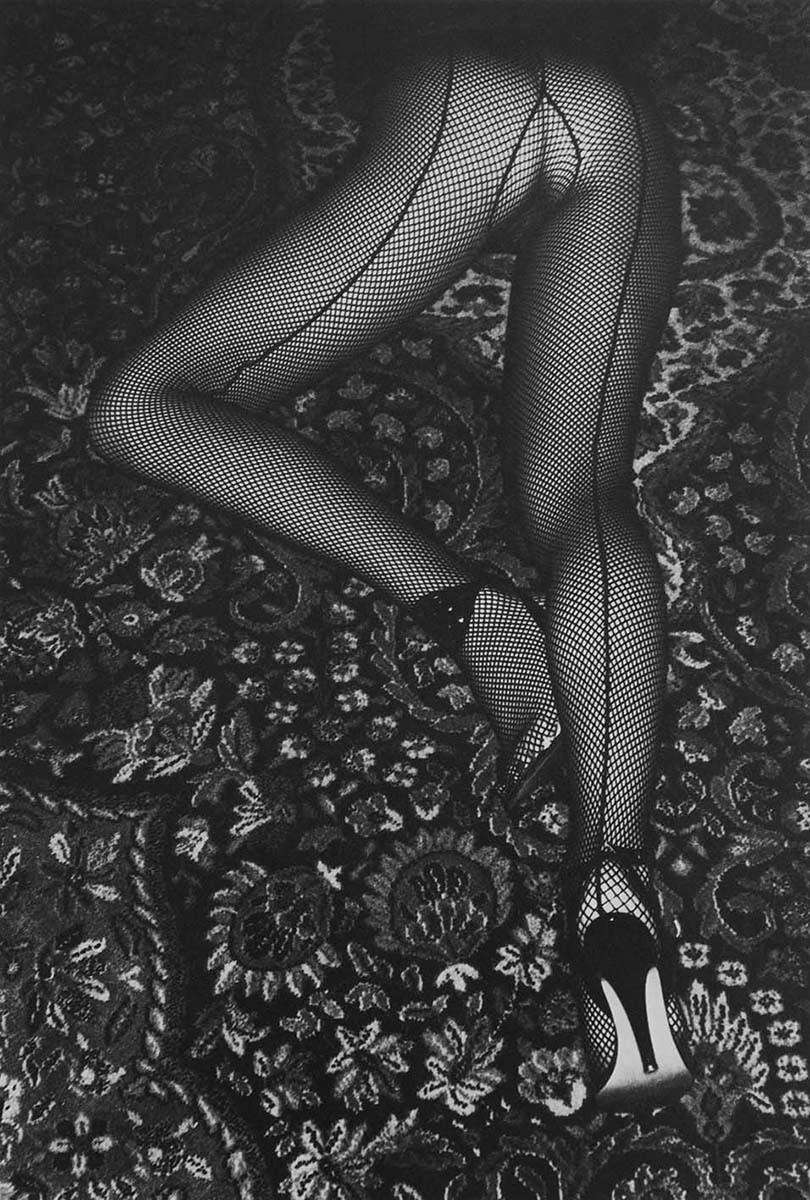

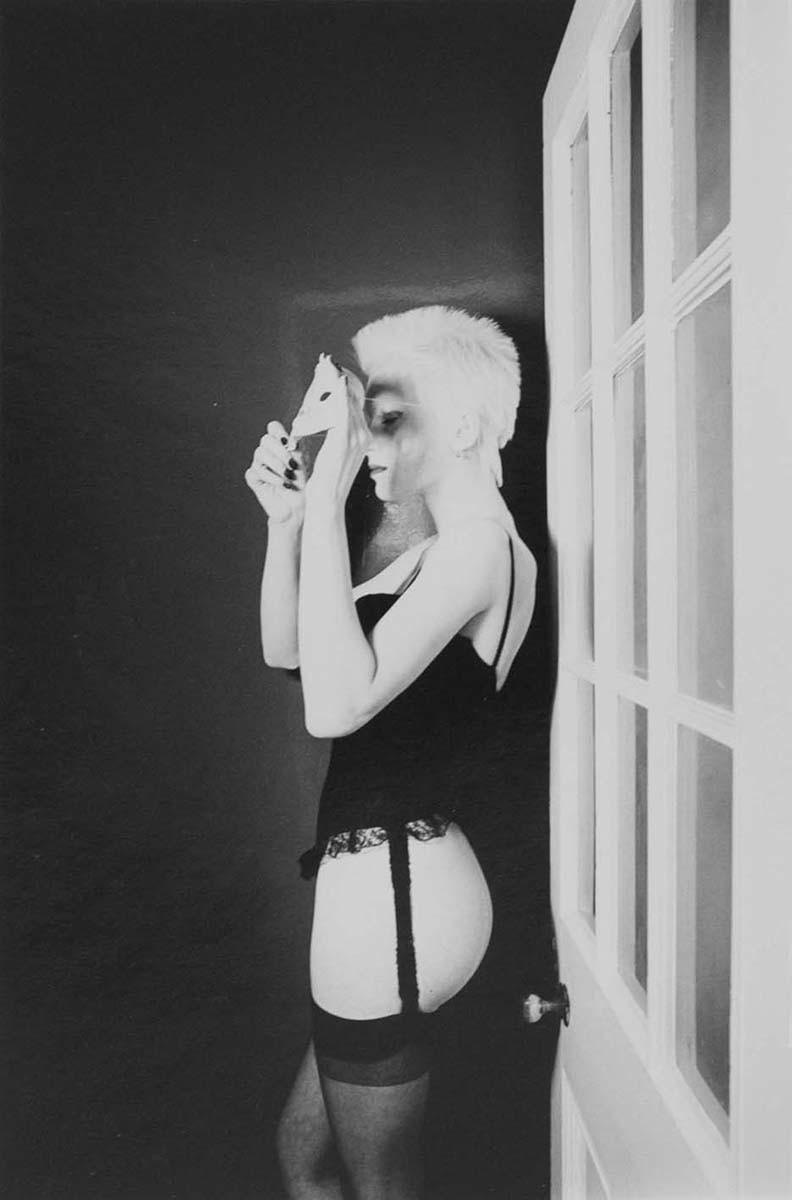

Laurence Sackman (1948 – 2020) started his career at the early sixties in the sulfurous world of fashion and advertising. His photographs were published in every great magazines of that time, Vogue, Stern, Sunday Times, Elle, Marie-Claire… The off-the-wall spirit of his photographs made him one of the most iconic photographers of the 70s and 80s, assisted by Paolo Roversi, and by the side of Guy Bourdin and Helmut Newton.

His photographs are powerful, explosive, and sometimes erotic, they witness the passion and craziness that inhabited him for decades. He had a great mastery of black and white and colors. Intense and raw, the use of these shades made his work singular.

Only a hundred prints are left from his career, most of them disappeared during his life. quoted from ODLP

In partnership with Fabienne Martin, the galerie in camera gallery lifts the veil on the work of Laurence Sackman, cult fashion photographer of the 1980s.

Laurence Sackman was born in 1948 in Wembley, a suburb of north London. He started out in photography at the age of 14, assisting still life photographer Sidney Pisan, who also practiced as a dentist. With Pisan, the young Sackman was initiated to the ring-flash that his mentor used in his medical practice and in his artistic activity. A few years later, Sackman was one of the first fashion photographers to use this type of shadow-reducing lighting.

Laurence Sackman’s contribution to photography cannot be reduced to pretty lights polished in the studio. His work, both poetic and subversive, strongly tinged with eroticism, had the imprint of a lively sensitivity. An era is reflected in it, where all daring was permitted.

His exceptional mastery and sharp gaze hatched on the cusp of the “swinging sixties”. London, the capital of pop culture, that blew a breath of freedom in art, music and fashion. Twenty years old in 1968, Sackman was part of this hedonistic youth, in full sexual liberation, eager to live in a more liberal and permissive society.

He began by photographing his relatives, his wife Rémi, his cousins. The star models of the decade posed in front of his lens: Anglo-Indian Chandrika Casali, muse of Guy Bourdin and David Bailey, the iconic Grace Jones, or Renate Zatsch, muse of Helmut Newton. Without forgetting Twiggy, emblematic model of the “swinging London”.

Laurence Sackman’s images are often transgressive. His signature was essential in magazines. He worked for Esquire, Stern, Queen, The Sunday Times, Nova, the New York Times. In Paris, the Jardin des Modes and Vogue Hommes requested him.

Friend of photographer Steve Hiett who introduced him in 1970 to Claude Brouet, editor-in-chief of Marie-Claire and to Emile Laugier, its talented artistic director, Sackman left no one indifferent. Emile Laugier remembers a young man with bright intelligent eyes, high standards, with very precise directing ideas, he knew exactly what he wanted. Alain Lekim, Laurence Sackman’s assistant for a few years, was so fascinated by the artist that he abandoned a very promising start to his career in photography to devote himself to him. The famous Paolo Roversi was his assistant. But then found Sackman “difficult to live with” but testifies “that he taught him everything”.

At that time, the name of Sackman was on everyone’s lips in the fashion microcosm. We only talked about his eccentricities, and, above all, his modernity, his inventiveness. Sackman carried out advertising campaigns for prominent brands: Saint-Laurent, Audi, De Beers.

One day, at the request of Yves Saint-Laurent himself, Sackman attended the preparatory meeting for a campaign where ideas were exchanged. What would he propose? To take pictures on the moon…

When asked about the posterity of his style, Helmut Newton saw himself with two heirs: Laurence Sackman and Chris von Wagenheim. In fact, Sackman was the referent photographer of the 80s.

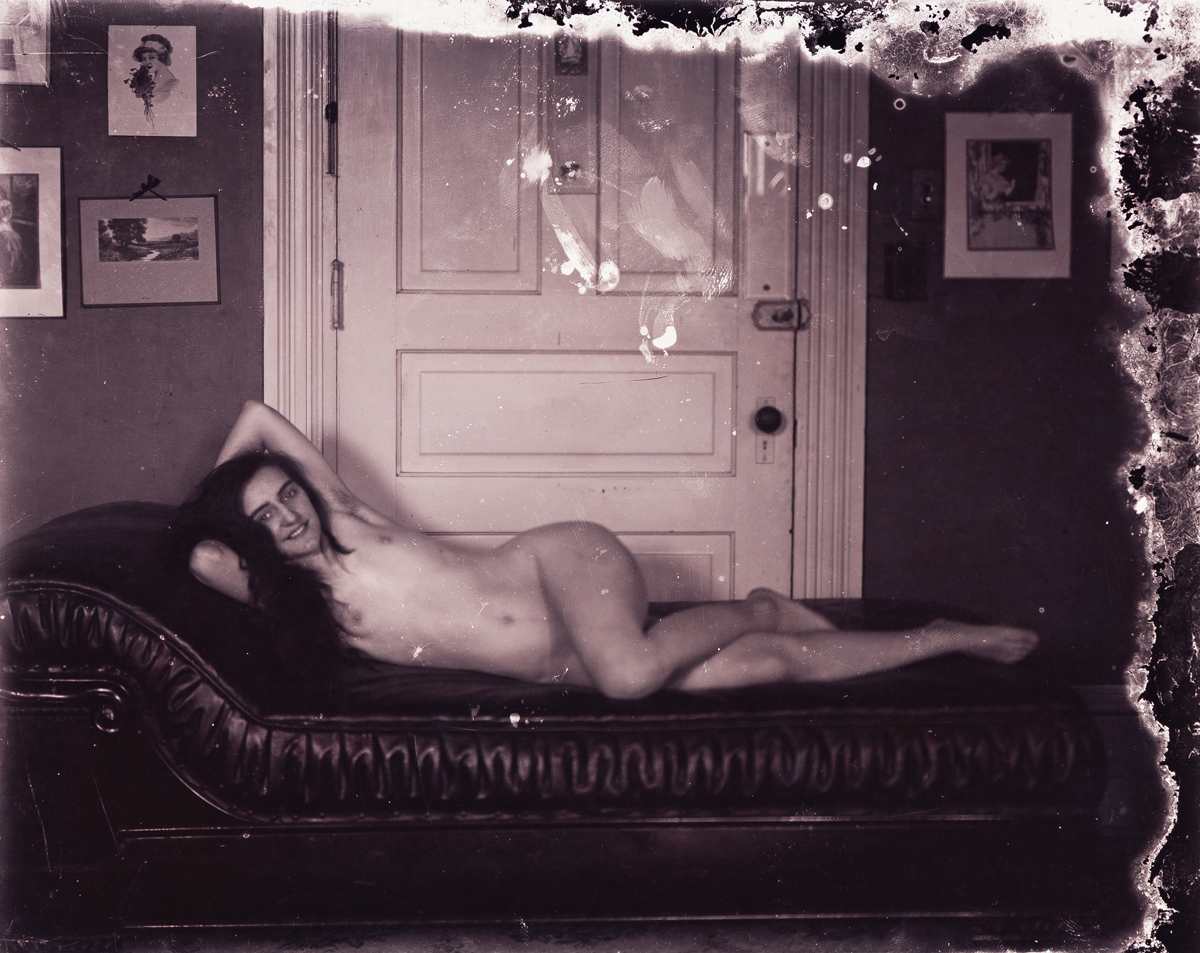

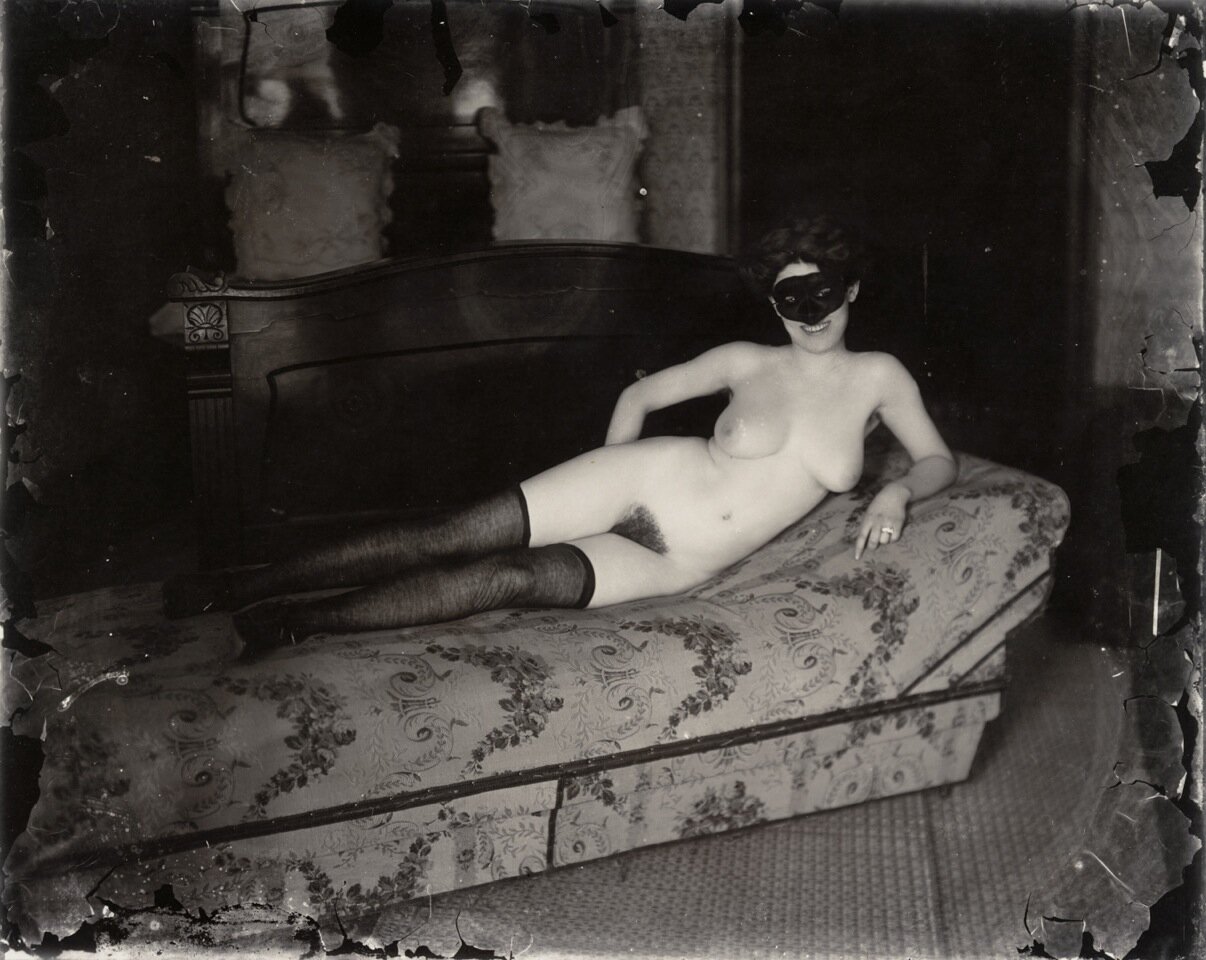

In 1983, he did his last opus, a series of nudes produced in room 65 of the Hotel La Louisiane, which became in a way his testament. According to him, the series constitutes his most successful work.

Suffering from psychiatric disorders, Laurence Sackman ended his photographic activity in 1984.

In this regard, he confided in 2017: “When I stopped photography, I felt like I had done everything I wanted to do. I had no regrets. I firmly believe that I would have repeated myself had I continued. ”

Such was Laurence Sackman, a celestial body, a comet that crossed the eighties.

Fabienne Martin (Galerie in camera)

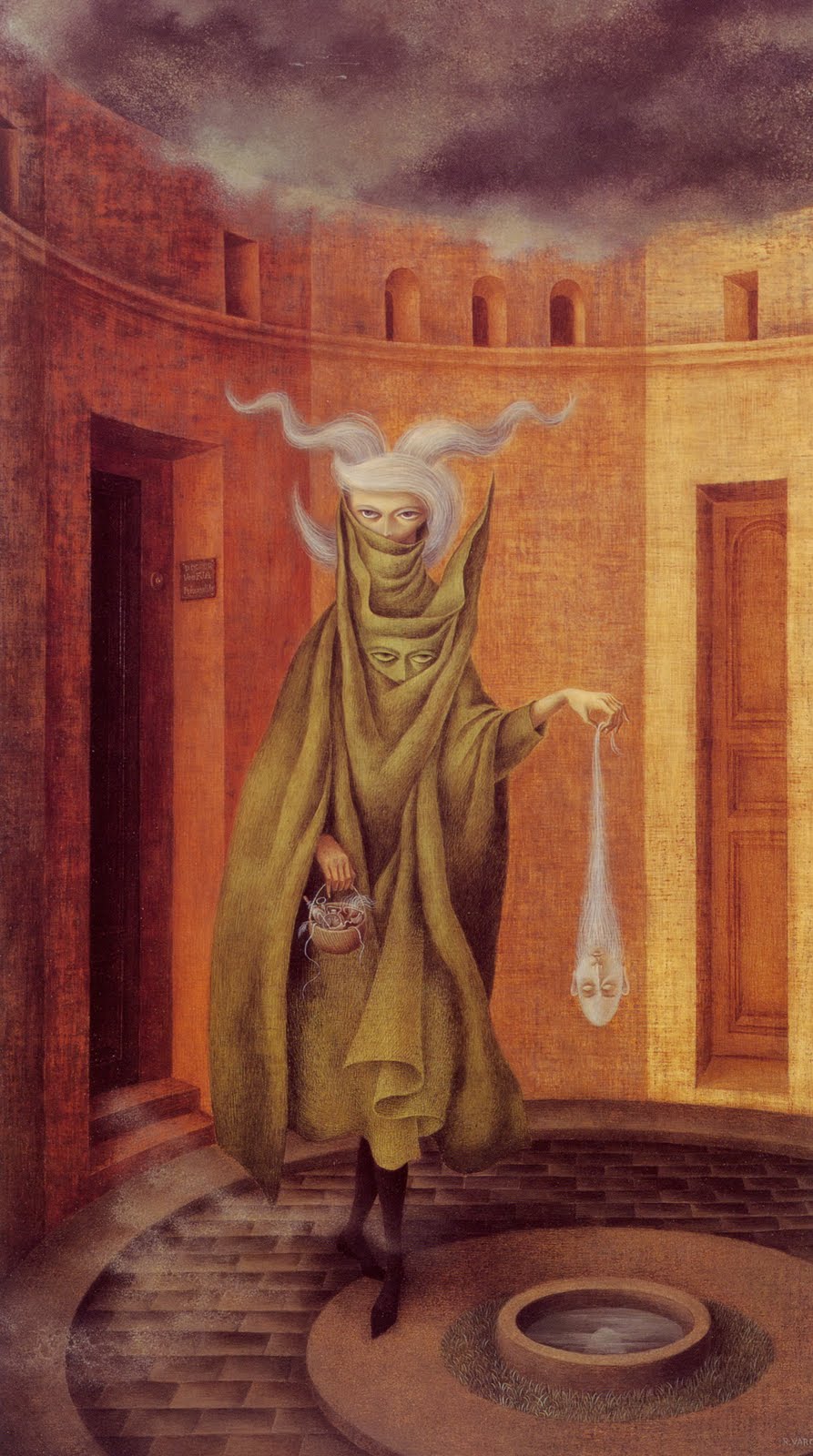

Mujer saliendo de psicoanalista es una escena onírica de luminosidad difusa, que muestra a una mujer recién salida de un consultorio de psicoanálisis; congelada en un movimiento sigiloso y elegante, está a punto de depositar la fantasmal cabeza de un hombre dentro de un pozo al centro de un patio interior circular, cubierto por nubes grisáceas. En la mano contraria lleva una pequeña canasta con “desperdicios psicológicos”, objetos simbólicos (un reloj, unas gafas, una botella de elíxir, una llave). A la altura del cuello, como parte de su vestimenta, asoma una especie de máscara, versión de su otro yo. El detalle de la cartela del consultorio dice: “Doctor FJA” y hace referencia a las iniciales de los apellidos de los doctores Sigmund Freud, Carl Gustav Jung y Alfred Adler. | src MAMM

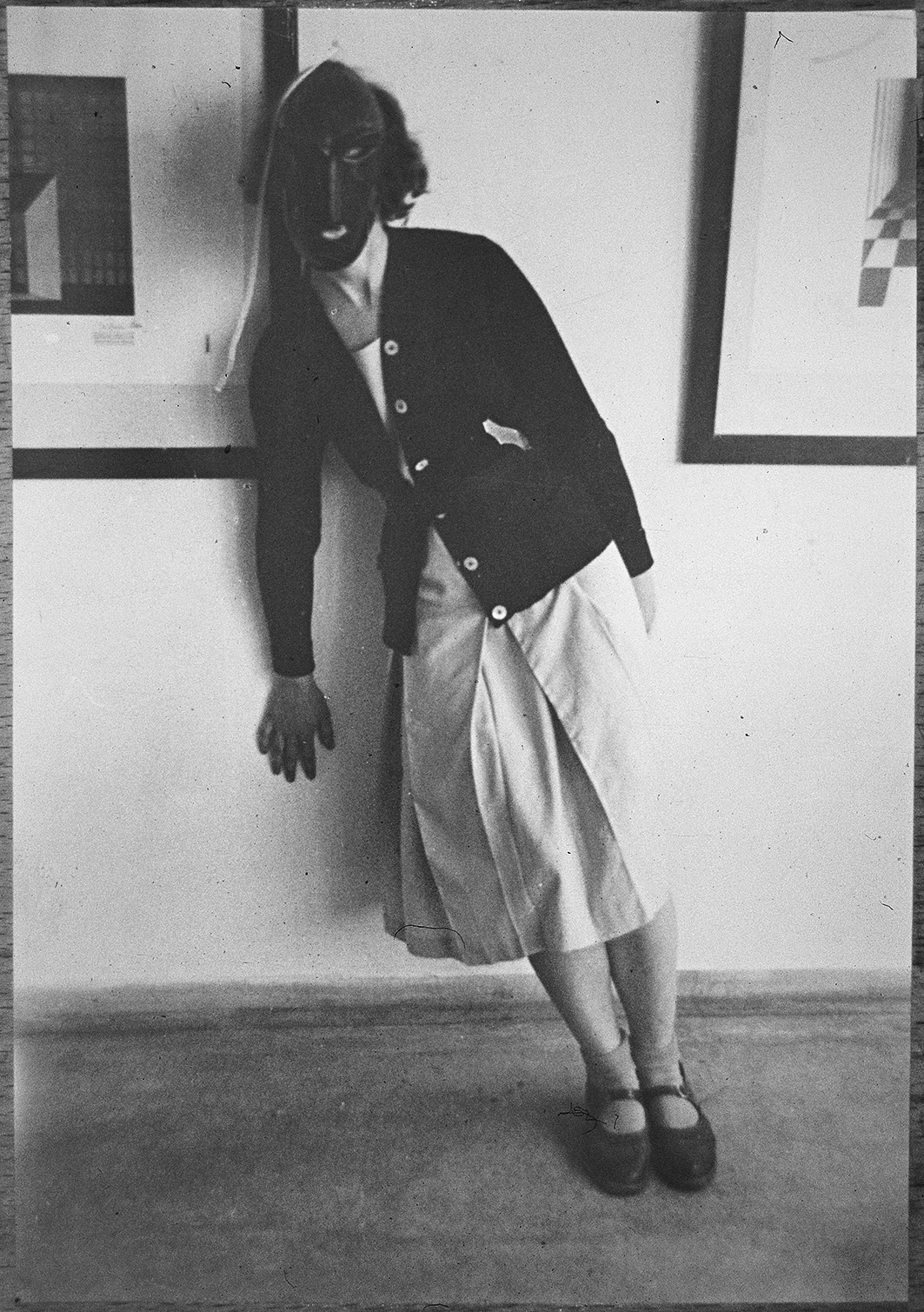

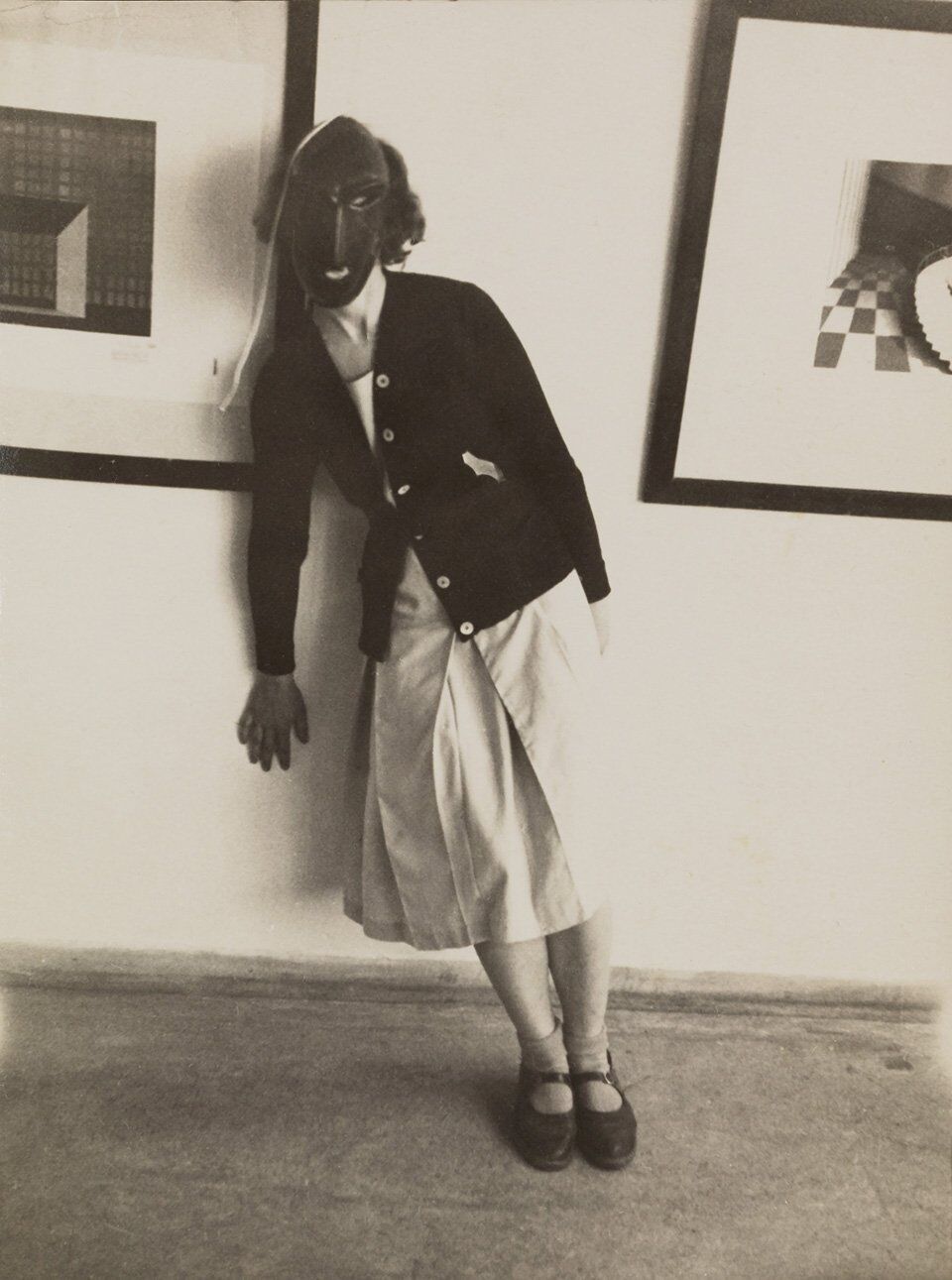

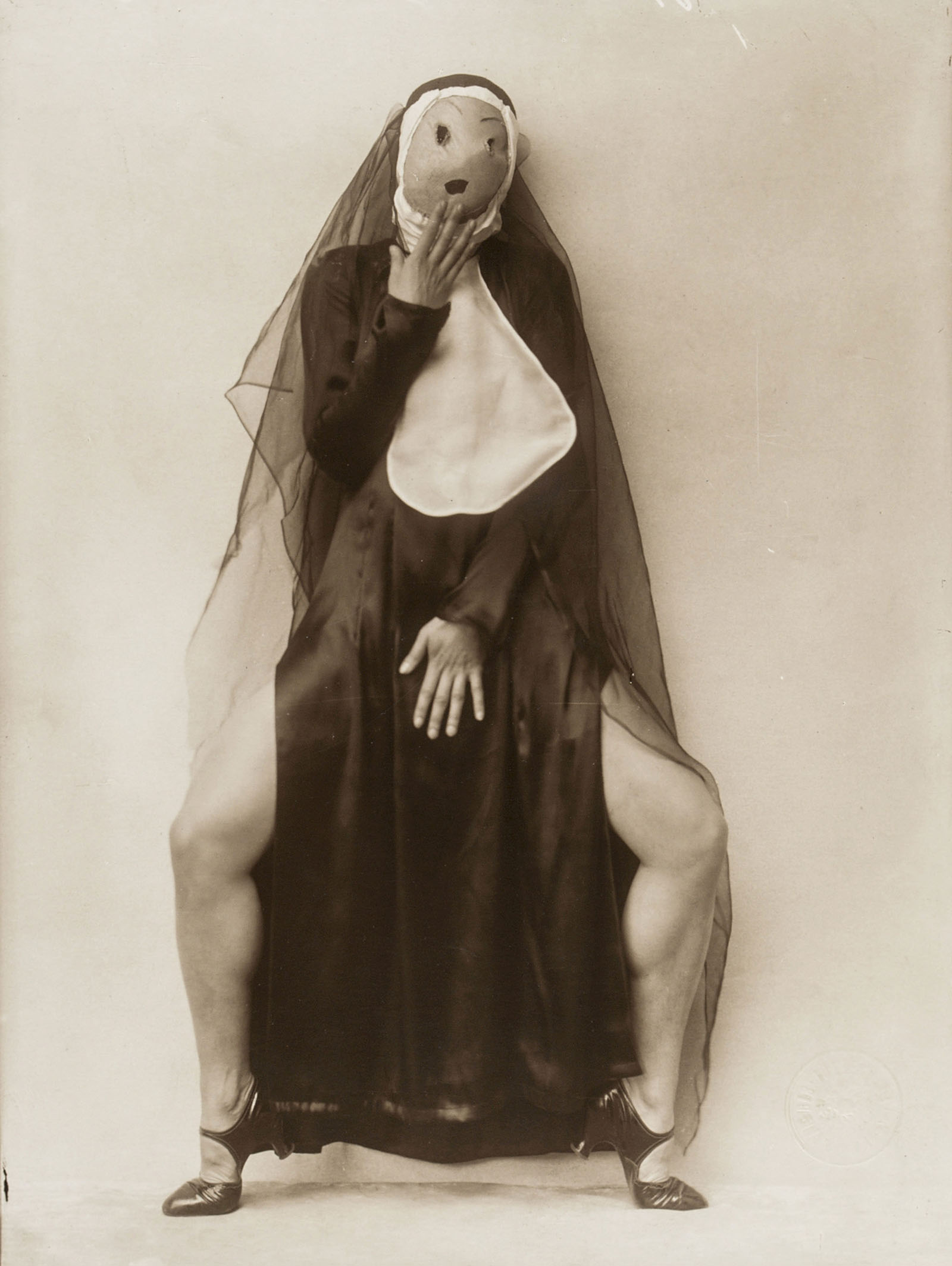

Role models. Many female dancers dealt with given role structures and criticized gender specific role attributions. The nun is seen as embodiment of a nonsexual woman who dedicates her life to God. Hence the play with the nun’s costume is a game with female physicality and sexuality. Here we meet Mura Ziperowitsch, who by wearing a nun similar costume refers to the female corporality.

source Vienna Pride at Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien