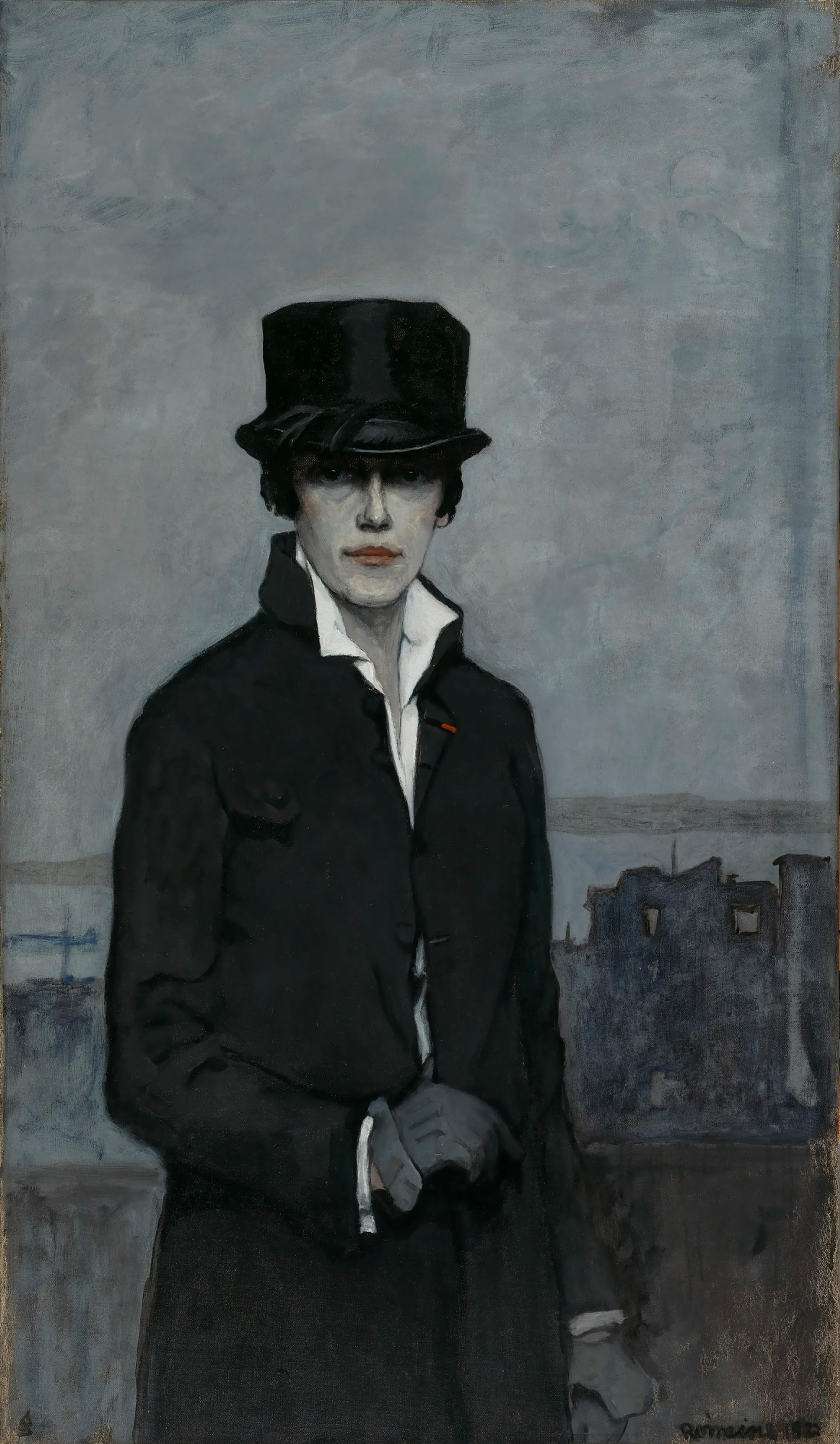

Peter depicts British painter Hannah Gluckstein, heir to a catering empire who adopted the genderless professional name Gluck in the early 1920s. By the time Brooks met her at one of Natalie Barney’s literary salons, Gluckstein had begun using the name Peyter (Peter) Gluck. She unapologetically wore men’s suits and fedoras, clearly asserting the association between androgyny and lesbian identity. Brooks’s carefully nuanced palette and quiet, empty space produced an image of refined and austere modernity. ~ The Art of Romaine Brooks, 2016

With this self-portrait, Brooks envisioned her modernity as an artist and a person. The modulated shades of gray, stylized forms, and psychological gravity exemplify her deep commitment to aesthetic principles. The shaded, direct gaze conveys a commanding and confident presence, an attitude more typically associated with her male counterparts. The riding hat and coat and masculine tailoring recall conventions of aristocratic portraiture while also evoking a chic androgyny associated with the post–World War I “new woman.” Brooks’s fashion choices also enabled upper-class lesbians to identify and acknowledge one another. ~ The Art of Romaine Brooks, 2016

Una Troubridge was a British aristocrat, literary translator, and the lover of Radclyffe Hall, author of the 1928 pathbreaking lesbian novel, The Well of Loneliness. Troubridge appears with a sense of formality and importance typical of upper-class portraiture, but with the sitter’s prized dachshunds in place of the traditional hunting dog. Troubridge’s impeccably tailored clothing, cravat, and bobbed hair convey the fashionable and daring androgyny associated with the so-called new woman. Her monocle suggested multiple symbolic associations to contemporary British audiences: it alluded to Troubridge’s upper-class status, her Englishness, her sense of rebellion, and possibly her lesbian identity. ~ The Art of Romaine Brooks, 2016

In La France Croisée, Brooks voiced her opposition to World War I and raised money for the Red Cross and French relief organizations. Ida Rubinstein was the model for this heroic figure posed in a nurse’s uniform, with cross emblazoned against her dark cloak, against a windswept landscape outside the burning city of Ypres. This symbolic portrait of a valiant France was exhibited in 1915 at the Bernheim Gallery in Paris, along with four accompanying sonnets written by Gabriele D’Annunzio. The gallery offered reproductions for sale as a benefit to the Red Cross. For her contributions to the war effort, the French government awarded Brooks the Cross of the Legion of Honor in 1920. This award is visible as the bright red spot on Brooks’s lapel in her 1923 Self-Portrait. ~ The Art of Romaine Brooks, 2016

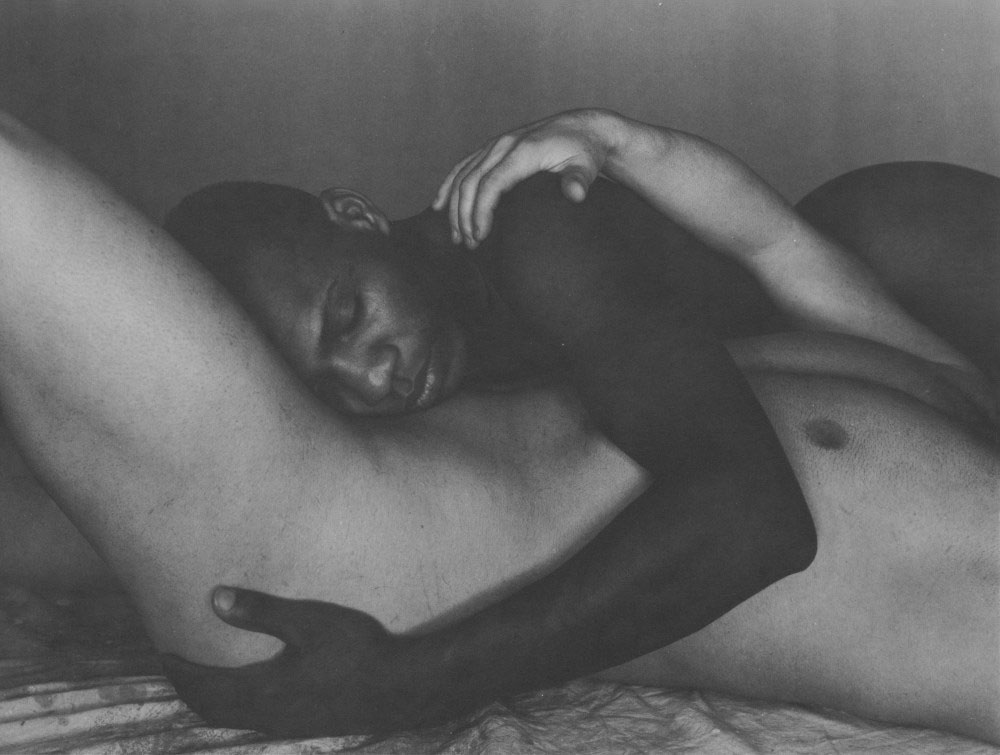

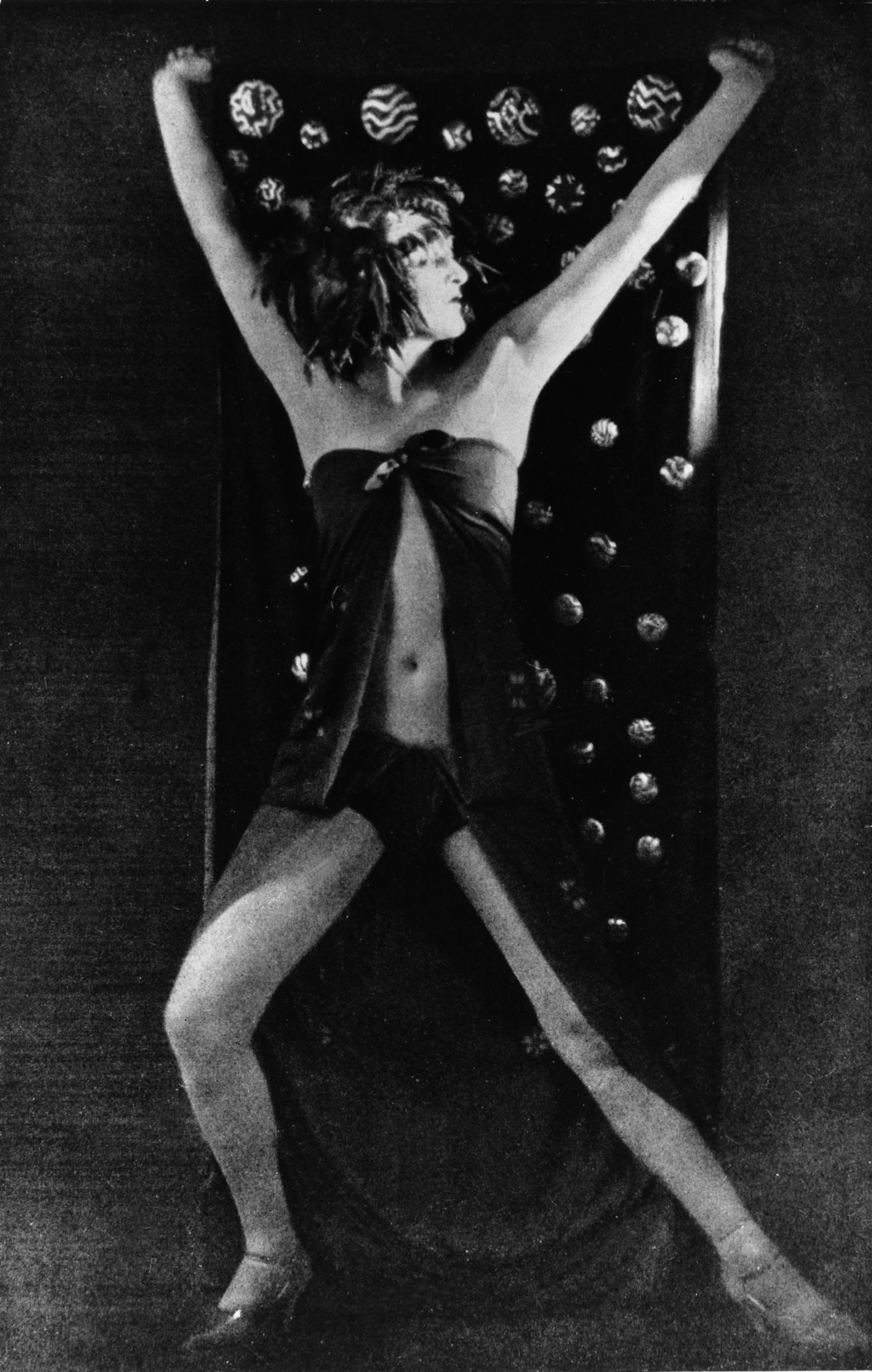

Brooks met Russian dancer and arts patron Ida Rubinstein in Paris after Rubinstein’s first performance as the title character in Gabriele D’Annunzio’s play The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian. Rubinstein was already well known for her refined beauty and expressive gestures; she secured her reputation as a daring performer by starring as the male saint in this boundary-pushing show that combined religious history, androgyny, and erotic narrative. Brooks found her ideal — and her artistic inspiration — in the tall, lithe, sensuous Rubinstein, who modeled for many sketches, paintings, and photographs Brooks produced during their relationship, from 1911 to 1914. In her autobiographical manuscript, “No Pleasant Memories,” Brooks said the inspiration for this portrait came as the two women walked through the Bois de Boulogne on a cold winter morning. ~ The Art of Romaine Brooks, 2016

All quotations and images (except n. 1 & 2) are from the Smithsonian American Art Museum (x)

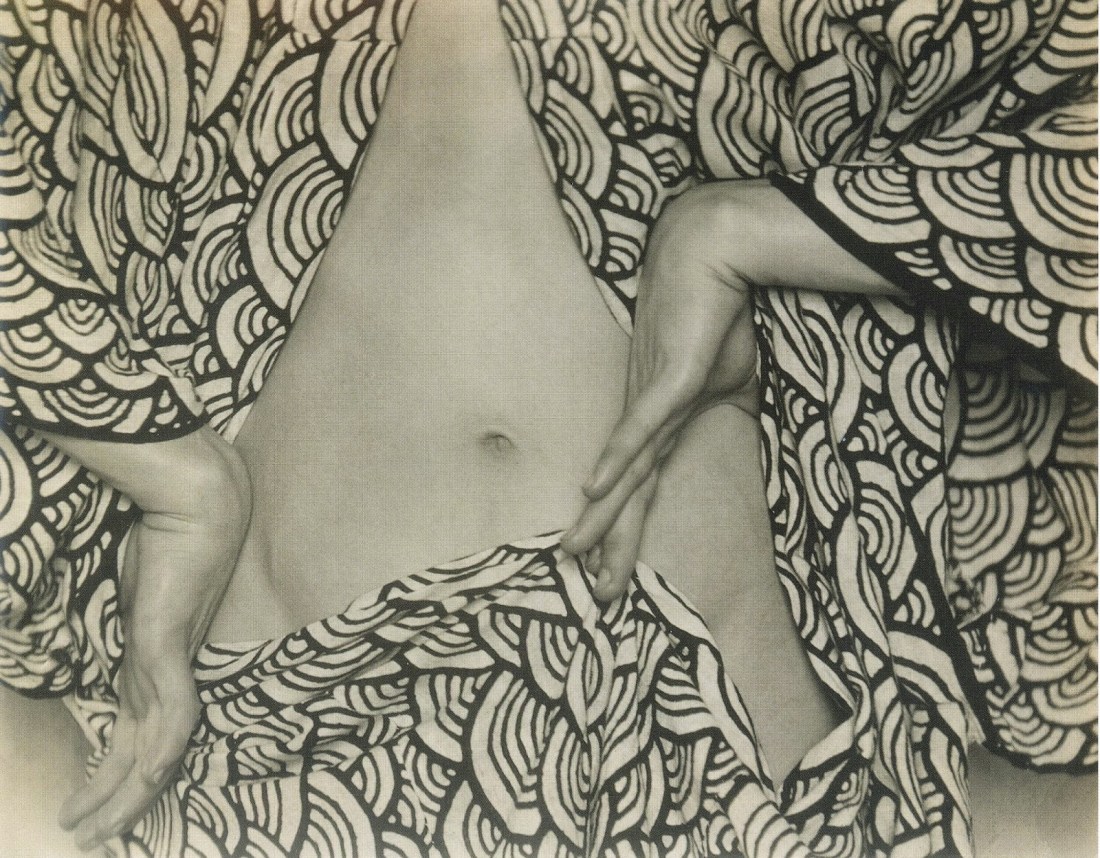

![Margrethe Mather :: Semi-nude [Billy Justema Wearing a Kimono], ca. 1923. Center for Creative Photography. University of Arizona, Tucson](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/margrethe-mather-semi-nude-billy-justema-wearing-a-kimono-ca.-1923-center-for-creative-photography-university-of-arizona-tucson.jpg)

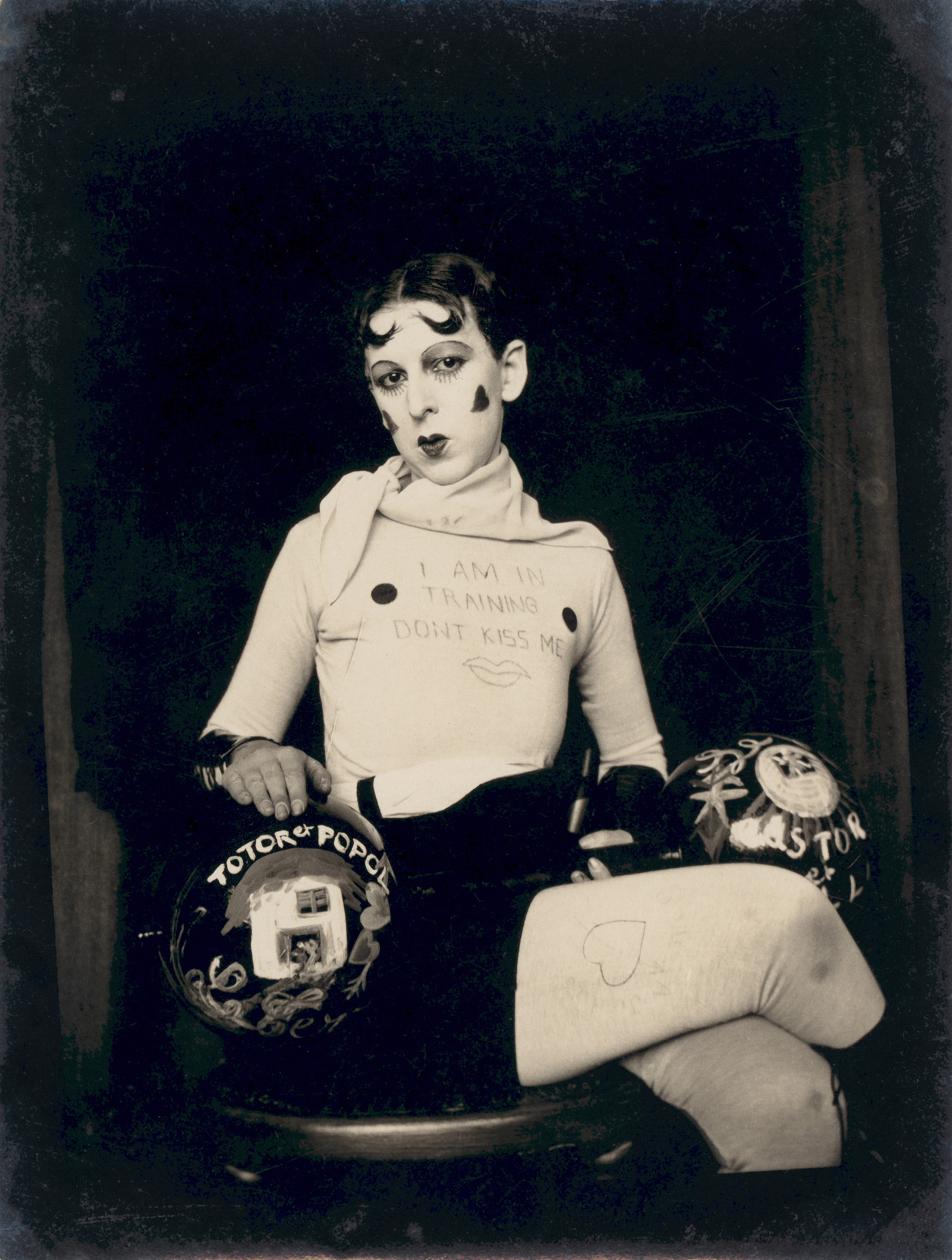

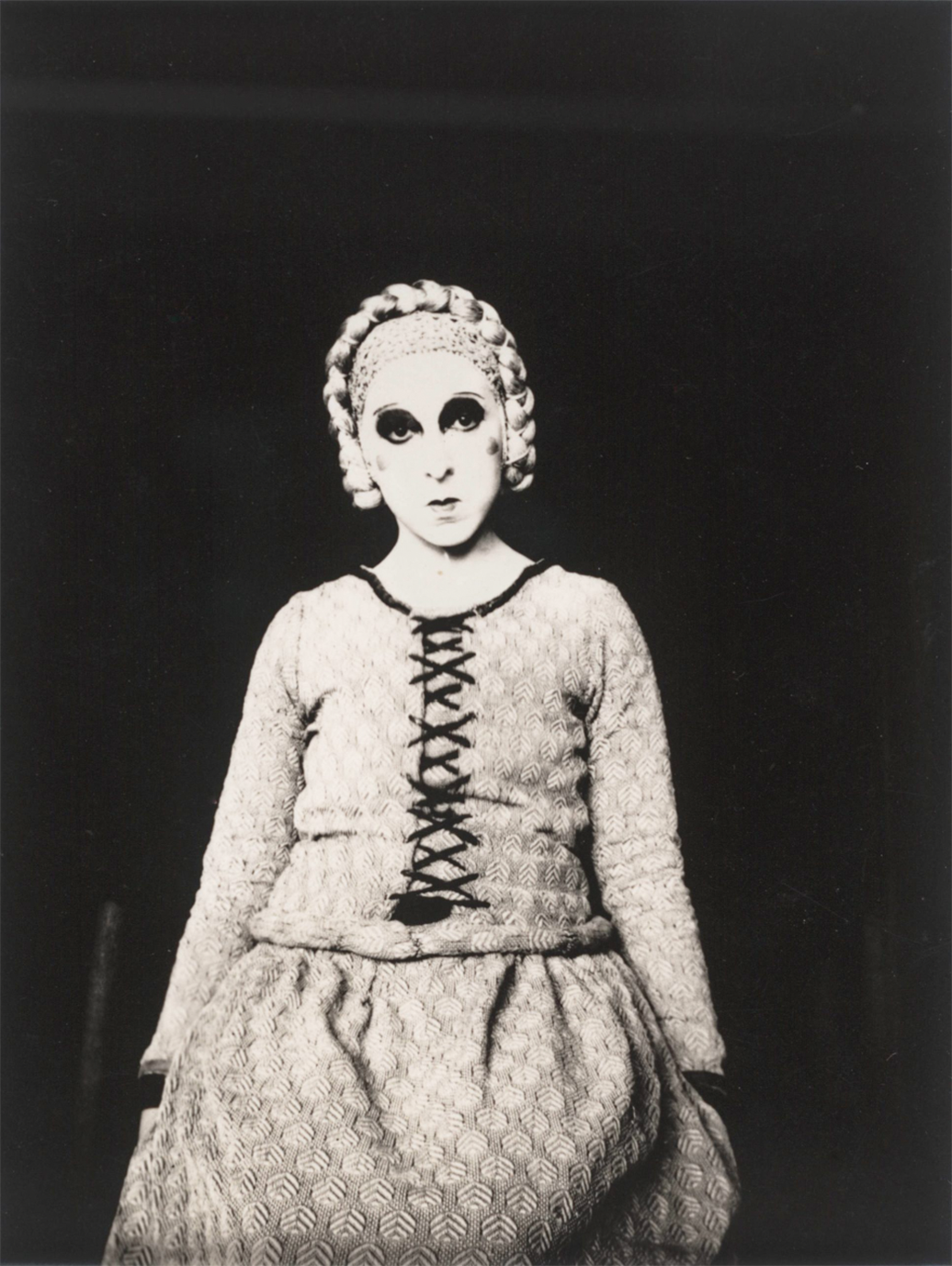

![Claude Cahun - Marcel Moore :: Untitled [Claude Cahun in Le Mystère d'Adam (The Mystery of Adam)], 1929. Detail. | src SF·MoMA](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52571360559_e9567f7a8e_o.jpg)