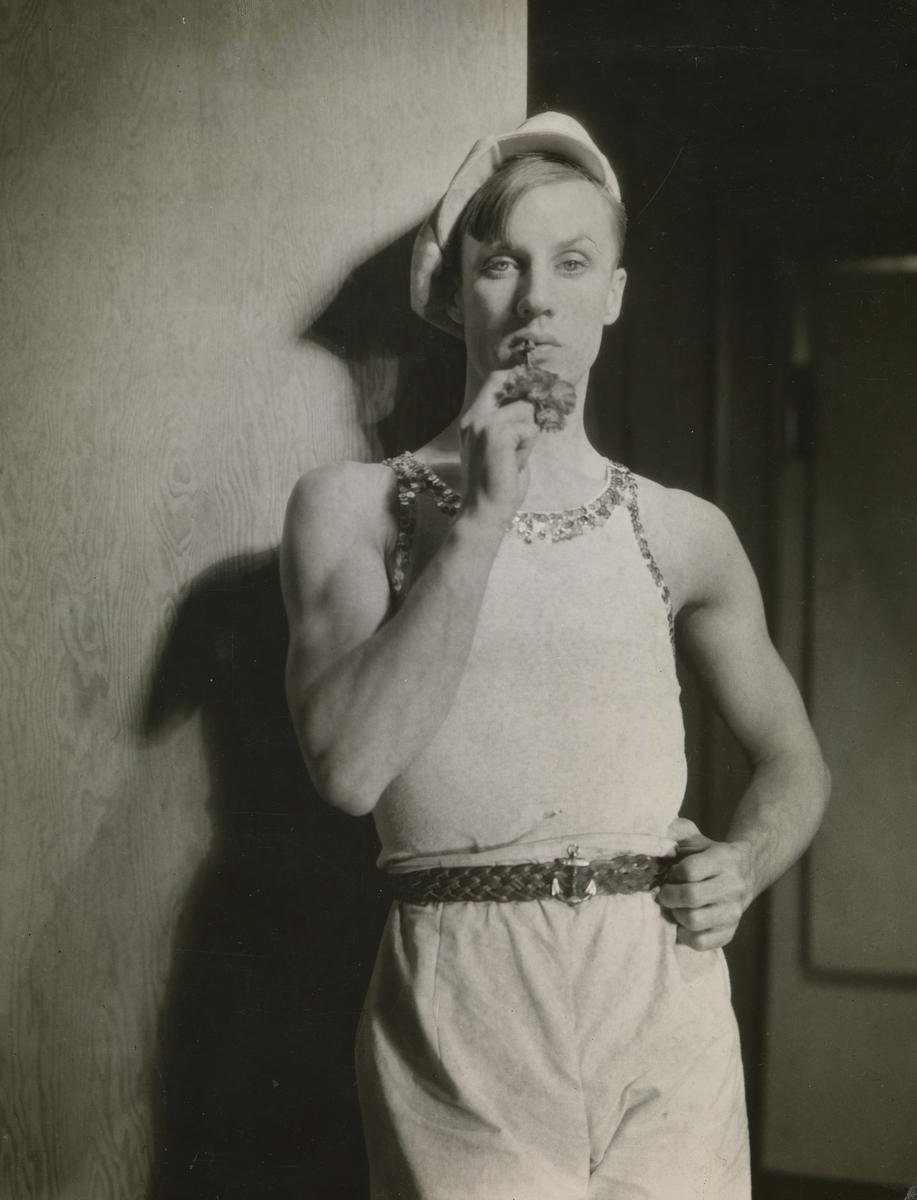

Album cover for I Am a Bird Now, second album by New York City based band Anohni and the Johnsons (previously Antony and the Johnsons); released on February 2005

images that haunt us

Album cover for I Am a Bird Now, second album by New York City based band Anohni and the Johnsons (previously Antony and the Johnsons); released on February 2005

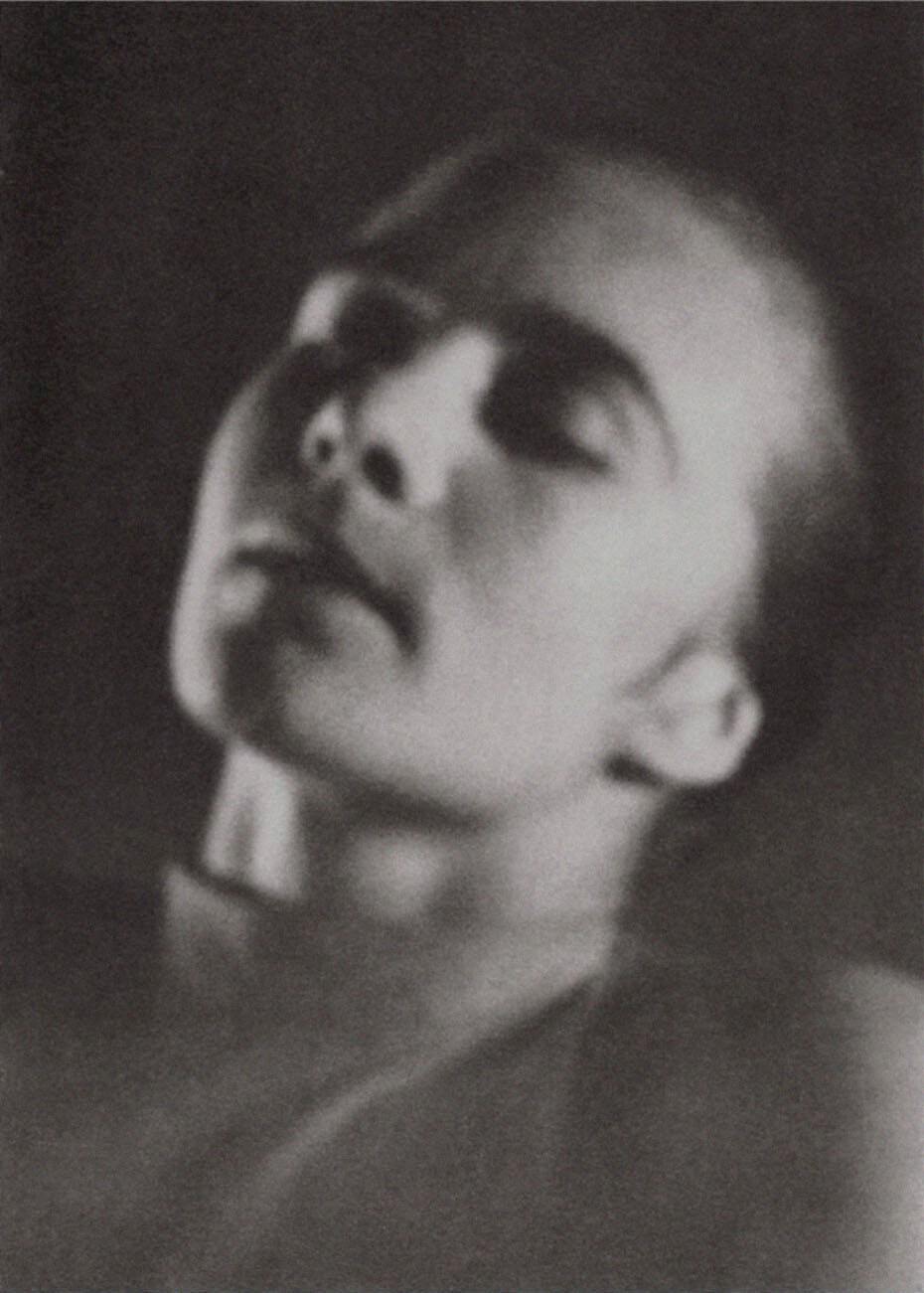

In Munich, Maja Lex was first a student member but soon, together with Gunild Keetmann and the founders Dorothee Günther and Carl Orff, belonged to the leading teaching staff of the Günther-Schule, a forward-looking school with a trebly diversified training concept of integrative musical and movement education. War events disrupted this unique constellation of artistic and educational personalities.

Maja Lex developed a new movement and dance education of a timeless pedagogic and artistic value. She liberated herself from the formalized practice/exercise/training and introduced instead the varied movements of rhythmic-dynamic, spatial and formal variation. Structured improvisation, similar to musical improvisation, was established as a definite component of the teaching lesson.

As a solo dancer and choreographer of Tanzgruppe Günther, Maja Lex was a pioneer of the New German Dance (Neuer Deutscher Tanz) in the 1930s. She created a specific dancing style of a ‘thrilling rhythmic intensity’, a definite feeling for form and a high technical dancing discipline. Music and dance became elements of equal value, not least because of the use of rhythm instruments for the dance and for the orchestra of Günther-Schule, where dancers and musicians changed roles. The director of the orchestra was Gunild Keetmann. Maja Lex’s dances belong to the absolute dance. / quoted from Elementarer Tanz

From 1927, Maja Lex performed her own choreographies. As a soloist and choreographer of the Tanzgruppe Günther-München (lead by Dorothee Günther), she made her decisive breakthrough in 1930 with the “Barbarian Suite” in collaboration with the musical director of the group, the composer Gunild Keetman. Numerous guest performances and awards at home and abroad followed until the school was forcibly closed in 1944 and finally destroyed in 1945.

Maja Lex, who had been very ill since the beginning of the 1940s, moved to Rome in 1948 and lived there together with Dorothee Günther in the house of her mutual friend Myriam Blanc. At the beginning of the 1950s Maja Lex resumed her artistic-pedagogical work and taught at the German Sport University Cologne at the invitation of Liselott Diem. From the mid-1950s until 1976, she taught the main training subject “Elementary Dance” as a senior lecturer. The concept of elementary dance was further developed by her and later in collaboration with her successor Graziela Padilla at the German Sports University Cologne. / quoted from queer places

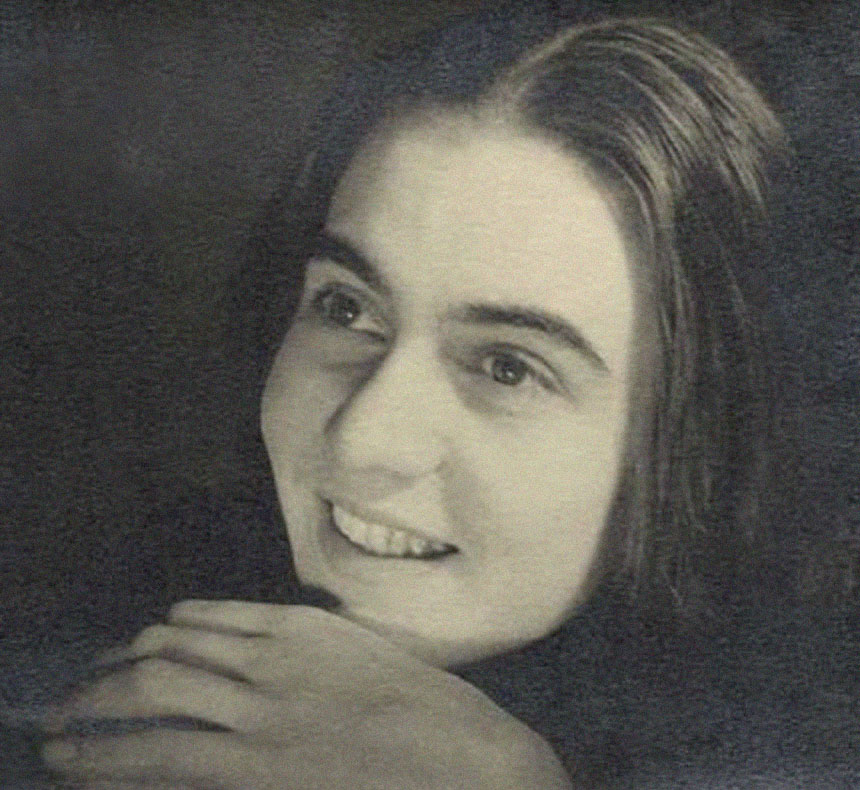

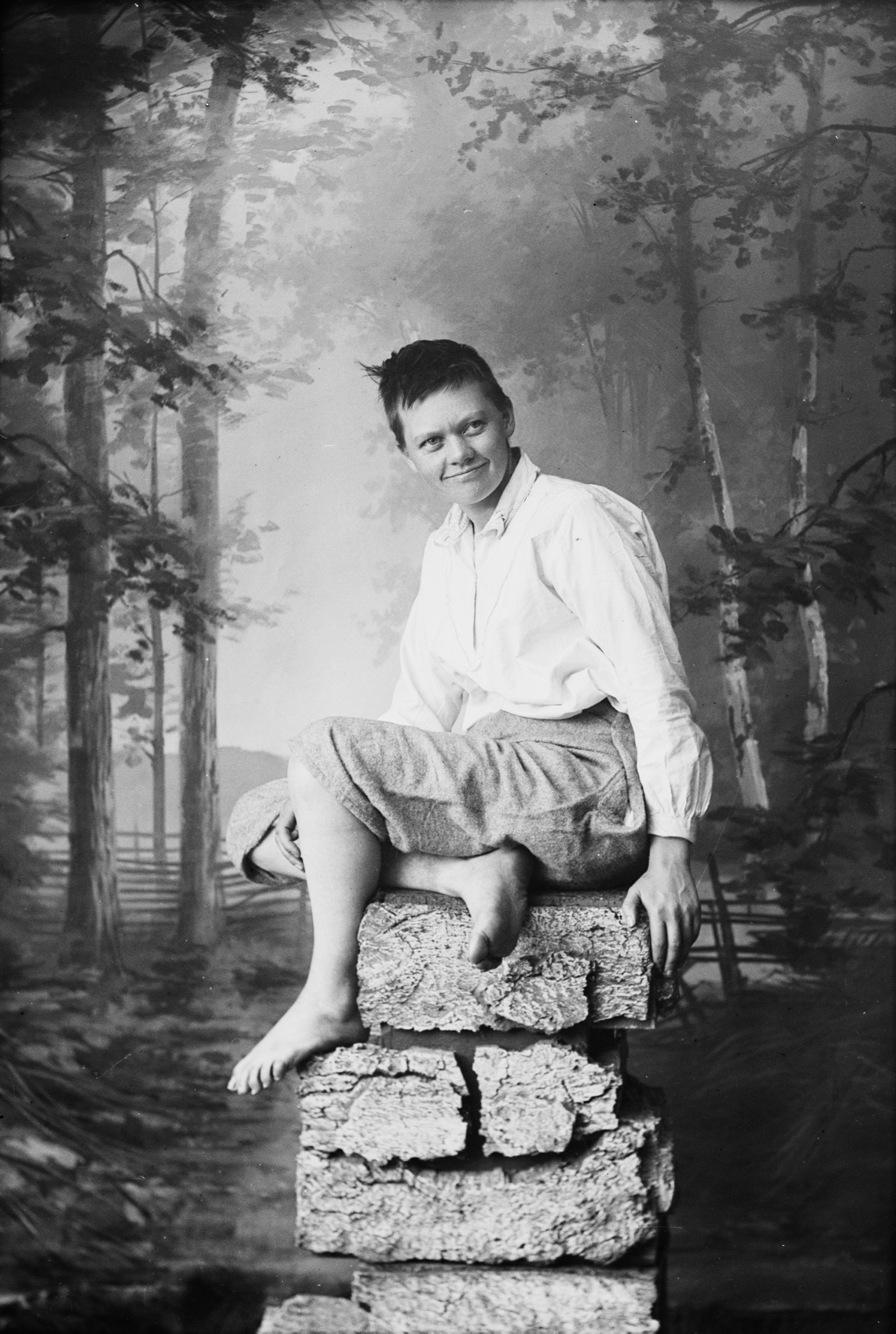

In a box marked “private”, an amazing collection of glass plates were found 30 years ago, amongst the remnants of the two portrait photographers Marie Høeg (1866-1949) and Bolette Berg (1872-1944).

In 1895, they established the Berg & Høeg photography studio in Horten, Norway, where they took portraits and views of Horten and surroundings and lived on the proceeds from sales. At that time, photography was seen as a decent and acceptable profession for women, as it was a profession that demanded a certain amount of aesthetic sense – as part of the female nature.

Horten was a naval base with the main shipyard for the Norwegian navy and had a strong flow of people who needed photographs for celebration and recollection. Perhaps that is how the two photographers understood by the very process of portraiture how important it is to stage oneself and to what a large degree that contributes to how we are perceived.

The Preus museum collection has 440 glass negatives from Berg & Høeg. Among the cartons in the 1980s were discovered some on which had been written “private.” It is not unusual that photographers also have private photographs in their archives. But these were not ordinary keepsake pictures. They indicate that the two photographers, especially Marie Høeg, experimented with various gender roles.

Imagine the fun they must have had, cross-dressing and playing! At the same time, the images are deeply serious, as they reflect upon the expectations and attitudes towards women, and their lack of rights and freedom. We know that Høeg was the extrovert and started groups to fight for women’s rights. Bolette Berg was less in the public view. However, she must have been back of the camera in many of these photographs, which have attracted international notice.

We find several such boundary-breaking photographic projects in Europe and America around 1900. They correspond with women’s battle for full civil rights and the right to define their own identity. So these photographs are a part of an international history – or herstory – that has meaning and recognition value for all women, including now.

All images are digital reproductions of the original glass plates. Some of the plates have cracks and damages, left visible in the reproductions.

All images and text retrieved from The Preus museum on Flickr

In a box marked “private”, an amazing collection of glassplates were found 30 years ago, amongst the remnants of the two portrait photographers Marie Høeg (1866-1949) and Bolette Berg (1872-1944).

In 1895, they established the Berg & Høeg photography studio in Horten, Norway, where they took portraits and views of Horten and surroundings and lived on the proceeds from sales. At that time, photography was seen as a decent and acceptable profession for women, as it was a profession that demanded a certain amount of aesthetic sense – as part of the female nature.

Horten was a naval base with the main shipyard for the Norwegian navy and had a strong flow of people who needed photographs for celebration and recollection. Perhaps that is how the two photographers understood by the very process of portraiture how important it is to stage oneself and to what a large degree that contributes to how we are perceived.

The Preus museum collection has 440 glass negatives from Berg & Høeg. Among the cartons in the 1980s were discovered some on which had been written “private.” It is not unusual that photographers also have private photographs in their archives. But these were not ordinary keepsake pictures. They indicate that the two photographers, especially Marie Høeg, experimented with various gender roles.

Imagine the fun they must have had, cross-dressing and playing! At the same time, the images are deeply serious, as they reflect upon the expectations and attitudes towards women, and their lack of rights and freedom. We know that Høeg was the extrovert and started groups to fight for women’s rights. Bolette Berg was less in the public view. However, she must have been back of the camera in many of these photographs, which have attracted international notice.

We find several such boundary-breaking photographic projects in Europe and America around 1900. They correspond with women’s battle for full civil rights and the right to define their own identity. So these photographs are a part of an international history – or herstory – that has meaning and recognition value for all women, including now.

All images are digital reproductions of the original glass plates. Some of the plates have cracks and damages, left visible in the reproductions.

All images and text retrieved from The Preus museum on Flickr

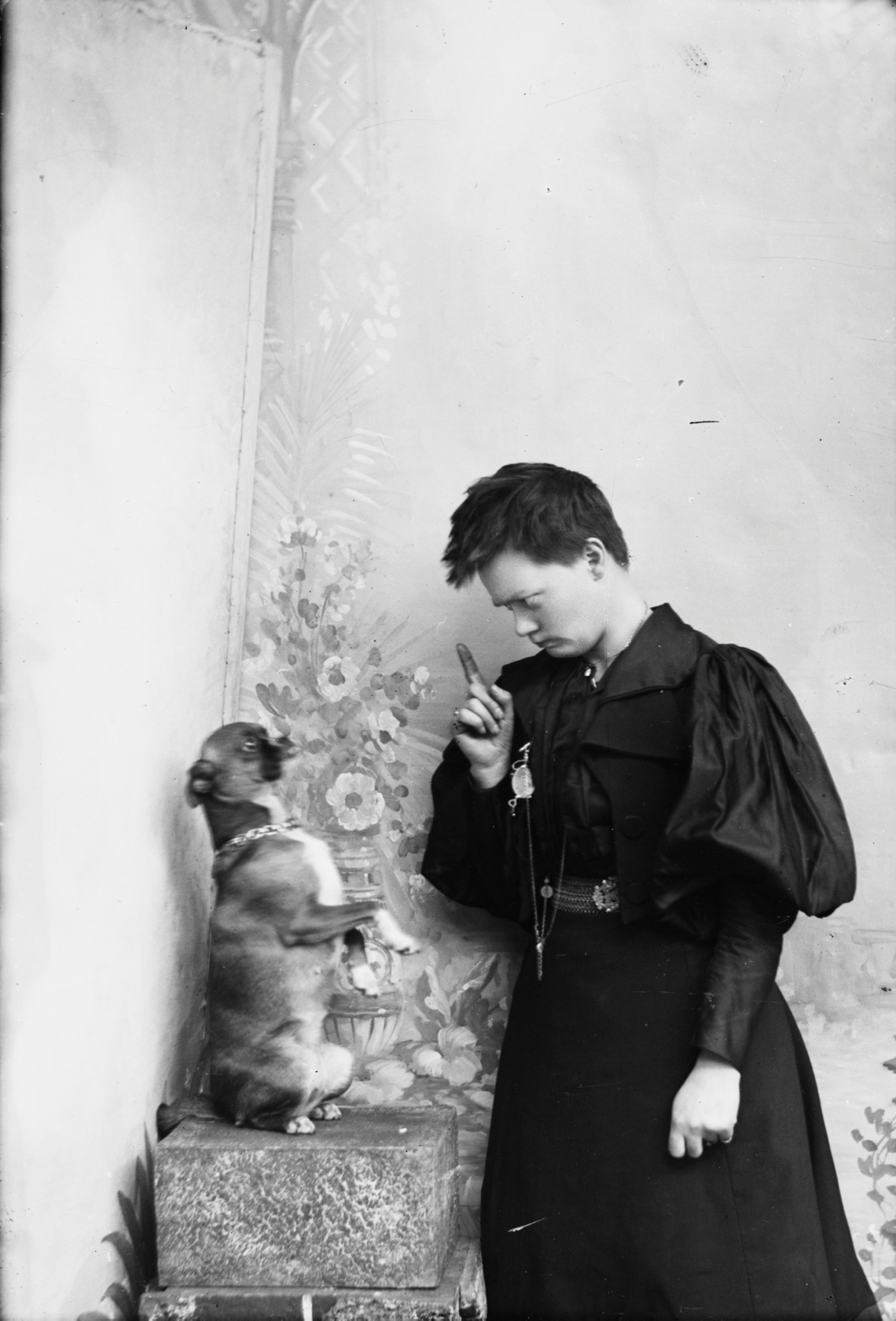

In a box marked “private”, an amazing collection of glass plates were found 30 years ago, amongst the remnants of the two portrait photographers Marie Høeg (1866-1949) and Bolette Berg (1872-1944).

In 1895, they established the Berg & Høeg photography studio in Horten, Norway, where they took portraits and views of Horten and surroundings and lived on the proceeds from sales. At that time, photography was seen as a decent and acceptable profession for women, as it was a profession that demanded a certain amount of aesthetic sense – as part of the female nature.

Horten was a naval base with the main shipyard for the Norwegian navy and had a strong flow of people who needed photographs for celebration and recollection. Perhaps that is how the two photographers understood by the very process of portraiture how important it is to stage oneself and to what a large degree that contributes to how we are perceived.

The Preus museum collection has 440 glass negatives from Berg & Høeg. Among the cartons in the 1980s were discovered some on which had been written “private.” It is not unusual that photographers also have private photographs in their archives. But these were not ordinary keepsake pictures. They indicate that the two photographers, especially Marie Høeg, experimented with various gender roles.

Imagine the fun they must have had, cross-dressing and playing! At the same time, the images are deeply serious, as they reflect upon the expectations and attitudes towards women, and their lack of rights and freedom. We know that Høeg was the extrovert and started groups to fight for women’s rights. Bolette Berg was less in the public view. However, she must have been back of the camera in many of these photographs, which have attracted international notice.

We find several such boundary-breaking photographic projects in Europe and America around 1900. They correspond with women’s battle for full civil rights and the right to define their own identity. So these photographs are a part of an international history – or herstory – that has meaning and recognition value for all women, including now.

All images are digital reproductions of the original glass plates. Some of the plates have cracks and damages, left visible in the reproductions. (quoted from the Album description)

All images from this post were retrieved from The Preus museum collection hosted on Flickr. Link to album (x)

Manuela von Meinhardis (Romy Schneider) enjoys the peace and quietness while fishing with her classmate Johanna (Paulette Dubost). A rare fun away from the strict girls’ school. Scene from Mädchen in Uniform, directed by Geza von Radvanyi (Germany / France, 1958). Produced by: Central Cinema Company Film (CCC)

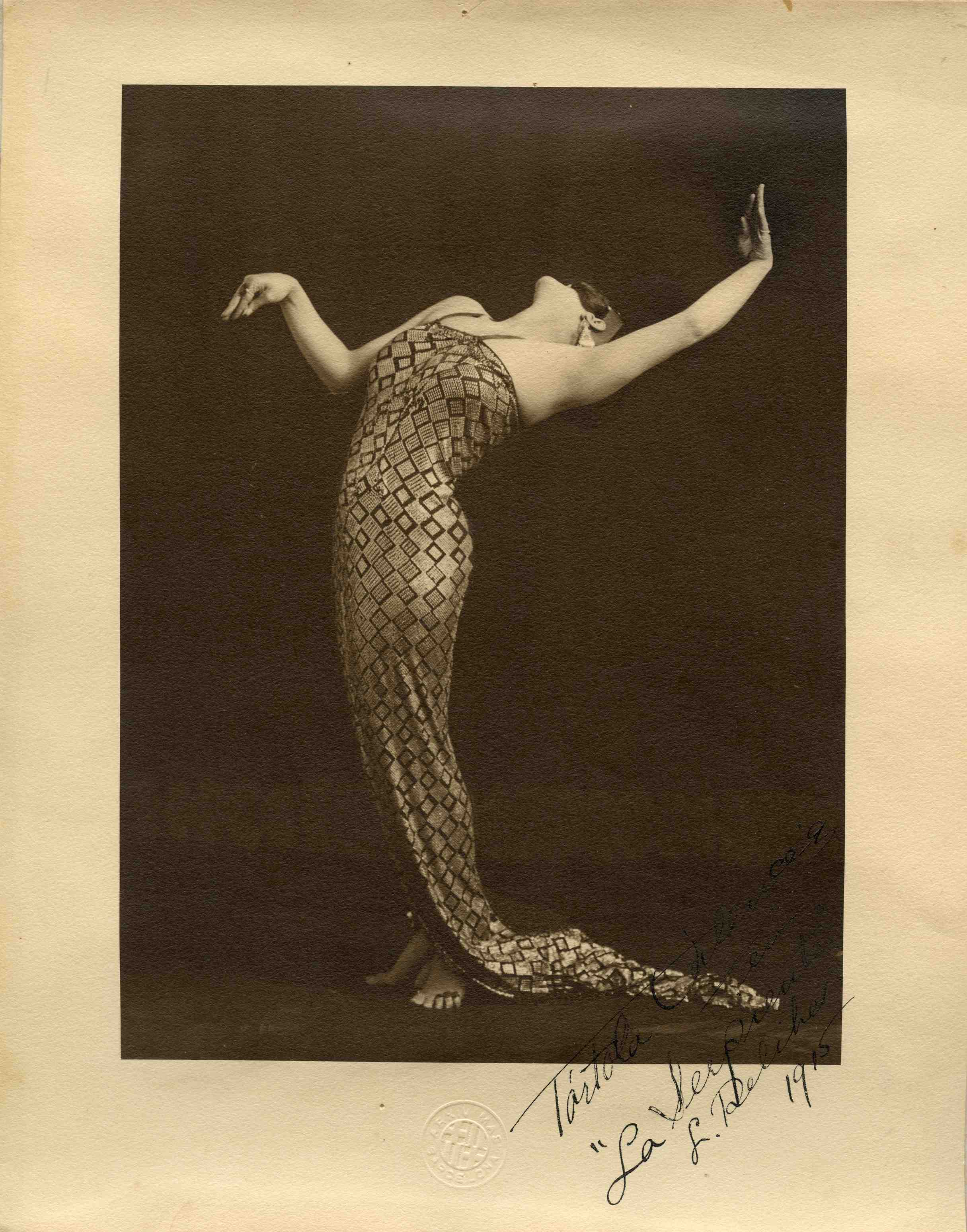

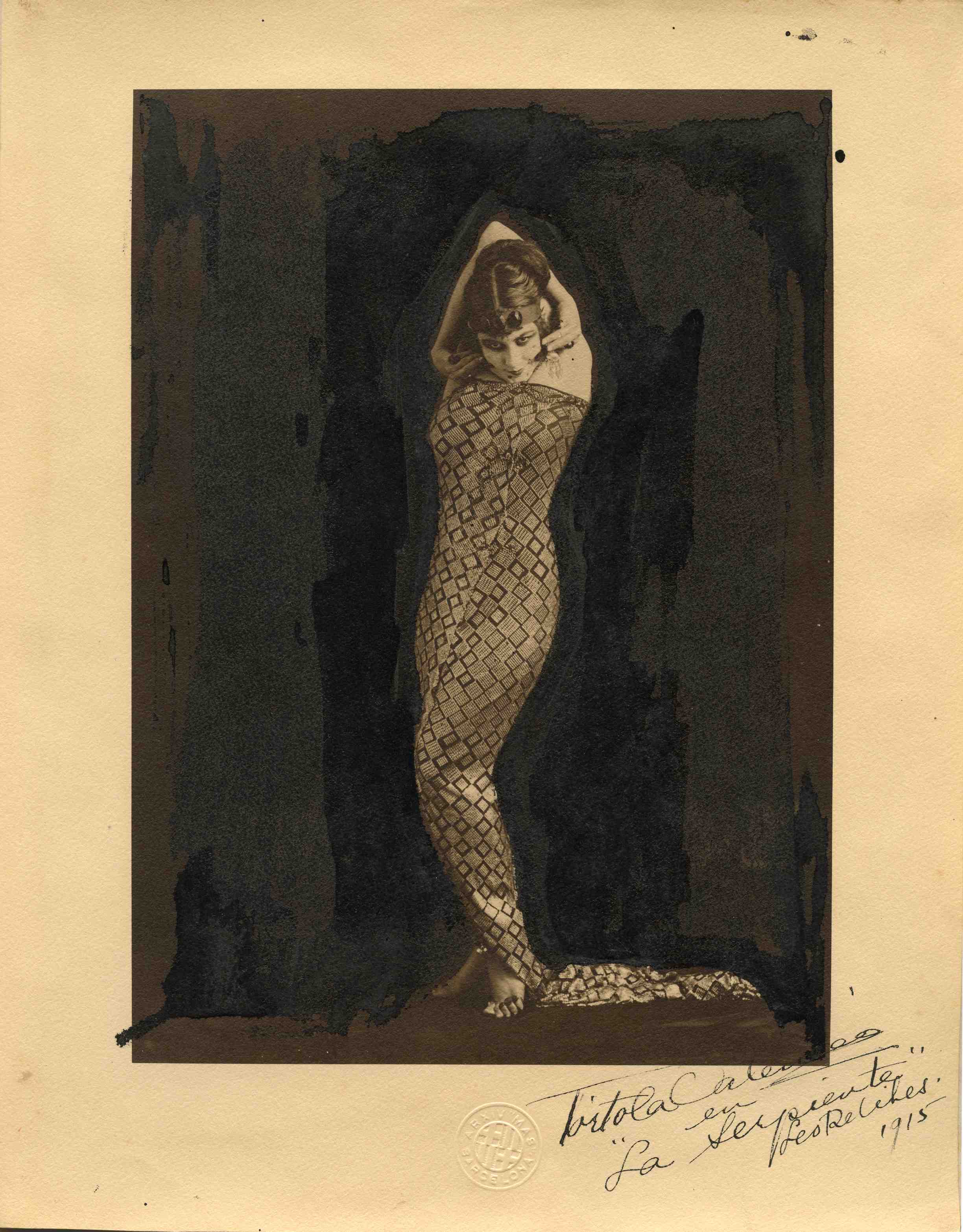

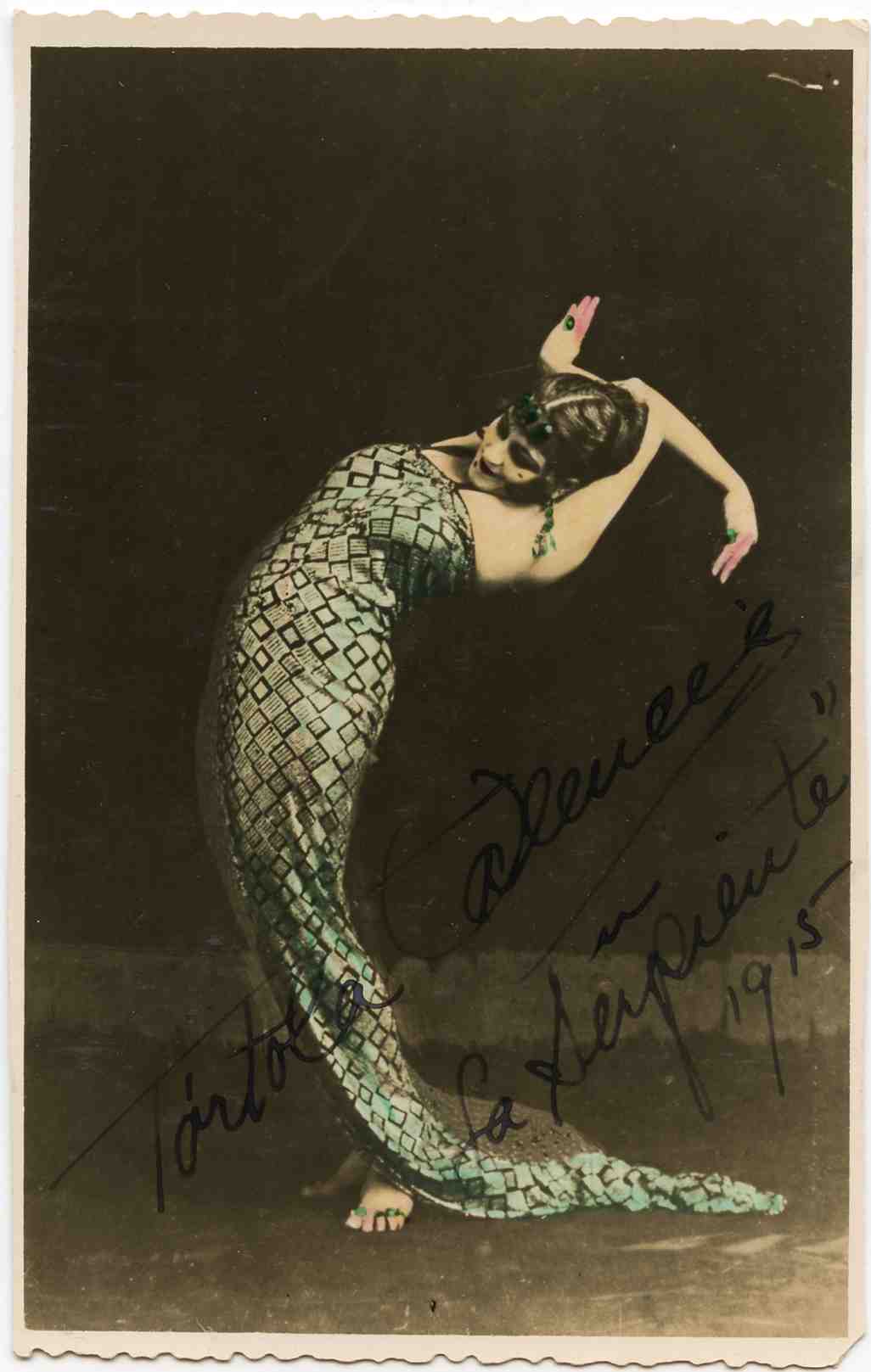

All images retrieved from Centre de Documentació i Museu de les Arts Escèniques (cdmae) / Arxiu Tórtola Valencia

El escritor Luis Antonio de Villena fue el recuperador de la figura de Tórtola en los artículos y prólogos que dedicó desde 1975 al novelista decadente Antonio de Hoyos y Vinent (éste fue uno de los tres hombres con los que se relacionó amorosamente a Tórtola)—los otros fueron el rey Alfonso XIII y el archiduque José de Baviera—. Con Antonio, Carmen solo compartió una densa amistad que les sirvió para ocultar sus verdaderas preferencias amorosas. Estos célebres nombres alimentaban el universo de Carmen que ella misma aderezaba a su antojo. Cuenta De Villena que cuando estrenó la llamada Danza incaica —inventada por ella misma— con un vestido lleno de tubitos color hueso, dijo que era un vestido hecho con huesos de los conquistadores. Nadie lo creía pero quedaba muy bien. Sin duda, la leyenda es parte de la creación del artista y en el periodo simbolista de entresiglos se dio abundantemente.

quoted from Jot down : Tórtola Valencia: entre la danza y el deseo

All images retrieved from Centre de Documentació i Museu de les Arts Escèniques (cdmae) / Arxiu Tórtola Valencia

Carmen Tórtola Valencia (Sevilla, 18 de junio de 1882 – Barcelona, 13 de febrero de 1955)

De padre catalán (Florenç Tórtola Ferrer) y madre andaluza (Georgina Valencia Valenzuela), cuando tenía tres años su familia emigró a Londres. Sus padres murieron en Oaxaca (México) en 1891 y 1894 respectivamente. Se ha especulado mucho sobre su misterioso origen; según algunos era una bastarda de la familia real española, según otros era hija de un noble inglés. En su libro Tórtola Valencia and Her Times (1982), Odelot Sobrac, uno de sus primeros biógrafos, afirma que desarrolló un estilo propio que expresaba la emoción con el movimiento y se inspiró al parecer en Isadora Duncan.

Especialista en danzas orientales, se interesó sobre todo por las danzas africanas, árabes e indias, que reinterpretó a su modo, investigando en todo tipo de bibliotecas; en cierto sentido llevó la antropología a la danza; su versatilidad como bailarina quedó sin embargo probada a lo largo de su vida. Su fama trascendió los límites profesionales a causa de sus innumerables amantes (gobernantes y escritores de renombre), por su belleza andaluza de ojos negros (fue considerada una de las mujeres más bellas de Europa) y por sus extensos conocimientos fruto de sus numerosos viajes y su pasión por la vida. Su primera aparición pública fue en 1908 en el Gaity Theatre de Londres como parte del espectáculo Habana.

Ese mismo año fue invitada a bailar en el Wintergarten y en el Folies Bergère. Allí fue denominada «La Bella Valencia», una nueva favorita del público como La Bella Otero o Raquel Meller. Al año siguiente bailó en Nürenberg y Londres. Fue invitada a unirse al Cirkus Varieté de Copenhague con Alice Réjane. Estuvo en Grecia, Rusia e India. Su debut español fue en 1911 en el Teatro Romea en Madrid. Volvió al mismo teatro en 1912. Fue nombrada en 1912 socia de honor y profesora estética del Gran Teatro de Arte de Múnich. En 1913 hizo una gira por España que incluyó el Ateneo de Madrid. En 1915 actuó con Raquel Meller en Barcelona.

En 1916, Tórtola fue caricaturizada en la revista de humor catalana Papitu como otra Mata Hari. Fue sin embargo su arte más bien apreciado por los intelectuales que por la gran masa del público. Emilia Pardo Bazán dijo de ella que era la personificación del Oriente y la reencarnación de Salomé. Tórtola fue una artista ecléctica y polifacética. En 1915 actuó en los filmes Pasionaria y Pacto de lágrimas, dirigidos por Joan Maria Codina. Viajó a Nueva York para actuar en el Century Theatre.

En 1920 la Galería Laietana de Barcelona exhibió 45 de sus pinturas sobre danza. Al año siguiente marchó de gira por Hispanoamérica. Entre 1921 y 1930 alcanzó allí una gran popularidad.

Fue una gran aficionada al arte precolombino, llegando a constituir una excelente colección de piezas procedentes de las más variadas civilizaciones del continente americano, especialmente de México y Perú.

Su independencia y vida desenvuelta fue sentida como una amenaza para los valores tradicionales de la sociedad española. Fue una pionera de la liberación de la mujer, como Isadora Duncan, Virginia Woolf y Sarah Bernhardt. Era budista y vegetariana, fue morfinómana y abogó por la abolición del corsé que impedía el libre movimiento femenino. Aunque tuvo numerosos amantes masculinos, sobre todo intelectuales, vivió la mayor parte de su vida con una mujer, Ángeles Magret Vilá, a la que adoptó como hija para guardar las apariencias. Quizá por ello defendió a capa y espada su intimidad y se destila de sus orígenes cierto misterio. Abandonó la danza el 23 de noviembre de 1930 en Guayaquil (Ecuador).

En 1931 se declaró republicana catalana y marchó a Barcelona con Ángeles. Dedicó los últimos años de su vida a coleccionar grabados y estampas y se inició en el budismo. Murió el 15 de marzo de 1955 en su casa del barrio de Sarriá en Barcelona. Creó la Danza del incienso, La bayadera, Danza africana, Danza de la serpiente y Danza árabe. Aparece como personaje en la novela Divino de Luis Antonio de Villena, y Ramón López Velarde le dedicó el poema Fábula dística. Prestó su imagen para el perfume “Maja” de la conocida casa de cosméticos Myrurgia.

Su contribución al arte de la danza consistió en una sensibilidad y orientación estética que ponían de manifiesto la sensualidad del cuerpo. La danza moderna, calificada entonces de irreverente por natural, respondía a sus ideales modernistas empapados de filosofías orientales.

El fondo de partituras de Tórtola Valencia se conserva en la Biblioteca de Cataluña. El resto, que incluye 112 piezas de indumentaria y complementos, 246 cuadros y dibujos, casi 1500 fotografías y carpetas de gran formato con carteles, fotografías, recortes e impresos y testigos de su vida artística y social se conserva en el Museo de las Artes Escénicas (MAE) del Instituto del Teatro de Barcelona. El MAE conserva además algunas tarjetas postales, programas de mano y 2 volúmenes de epistolario con el título genérico de “Los poetas a Tórtola Valencia”.

quoted from the wikipedia entry (in Spanish)