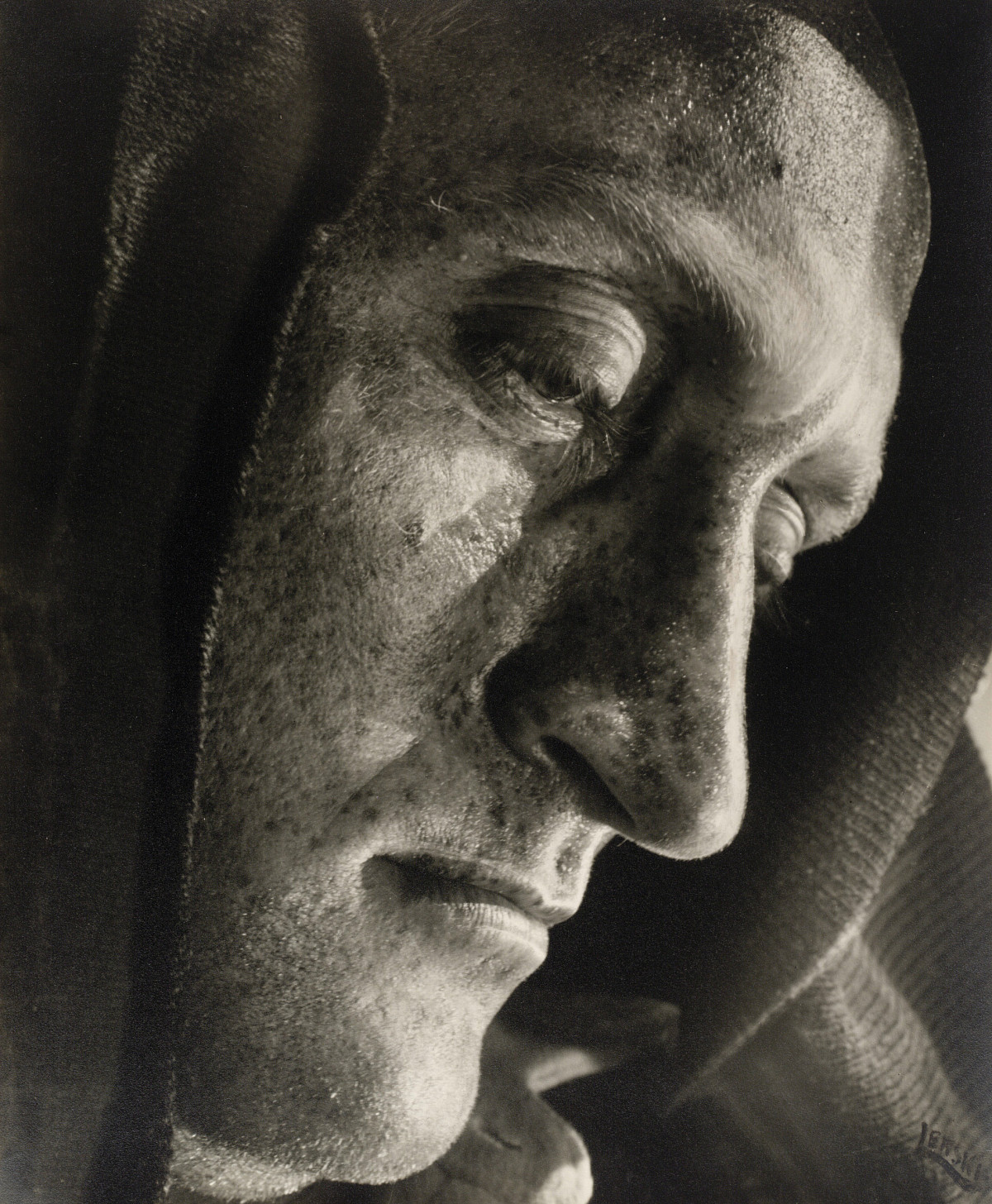

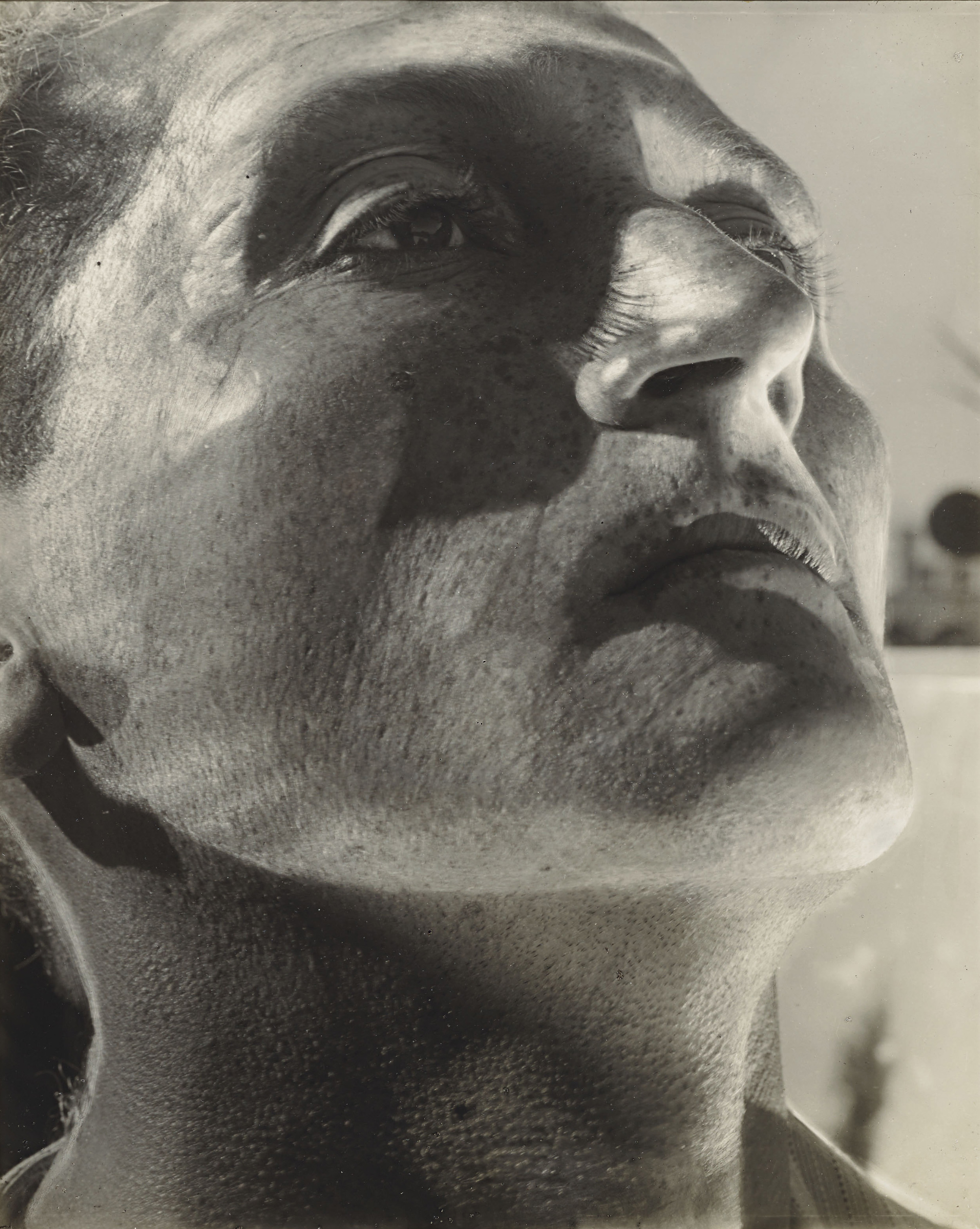

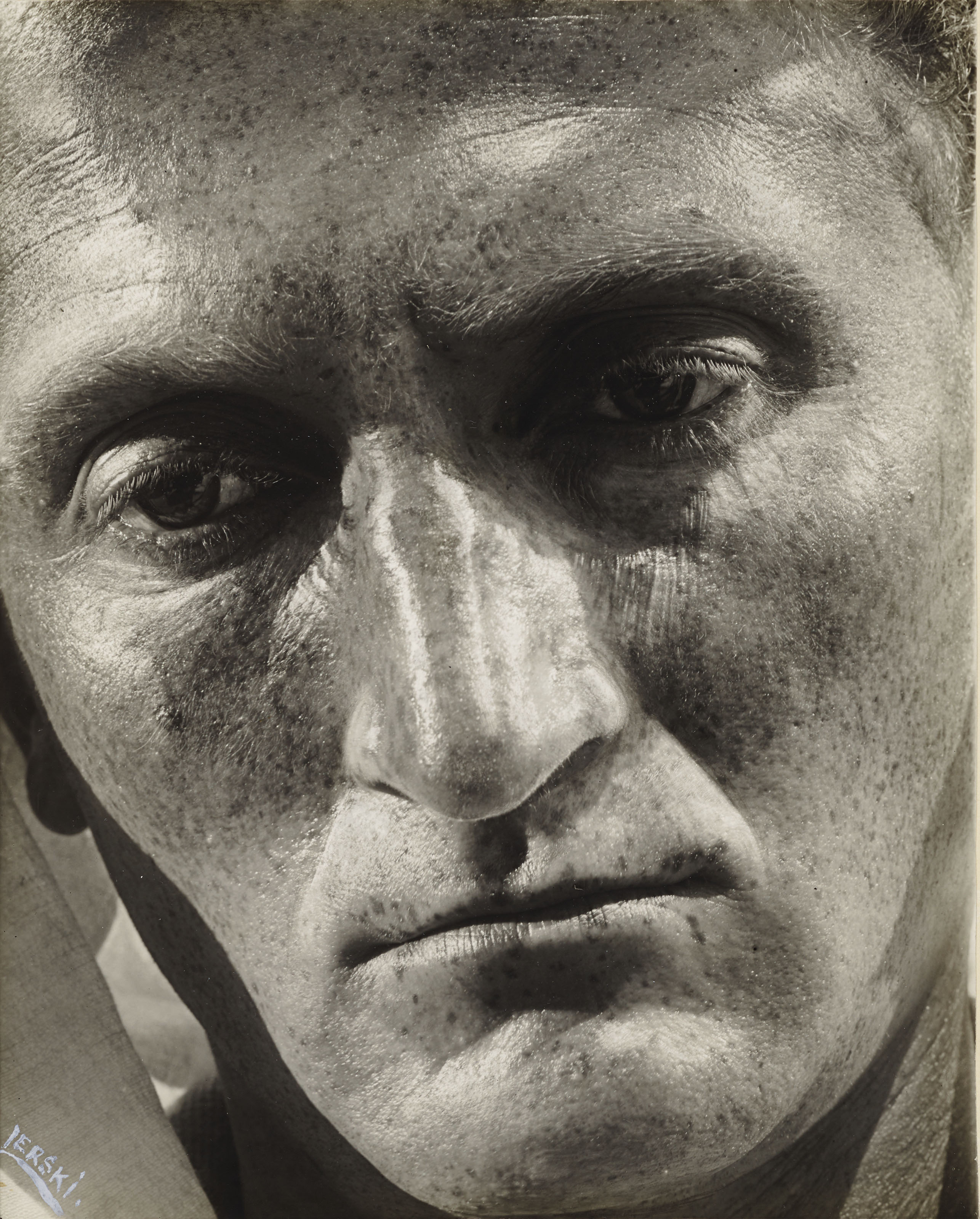

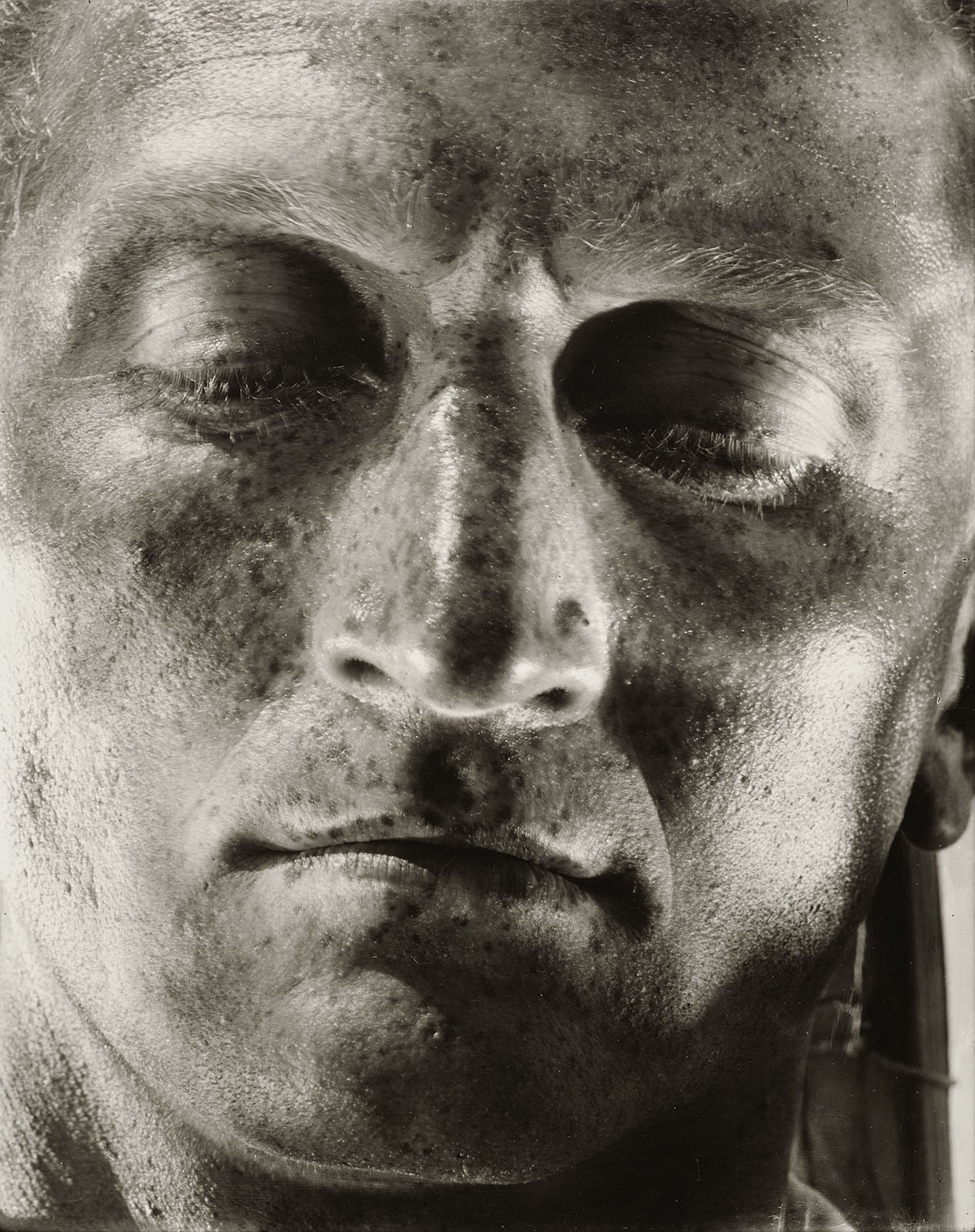

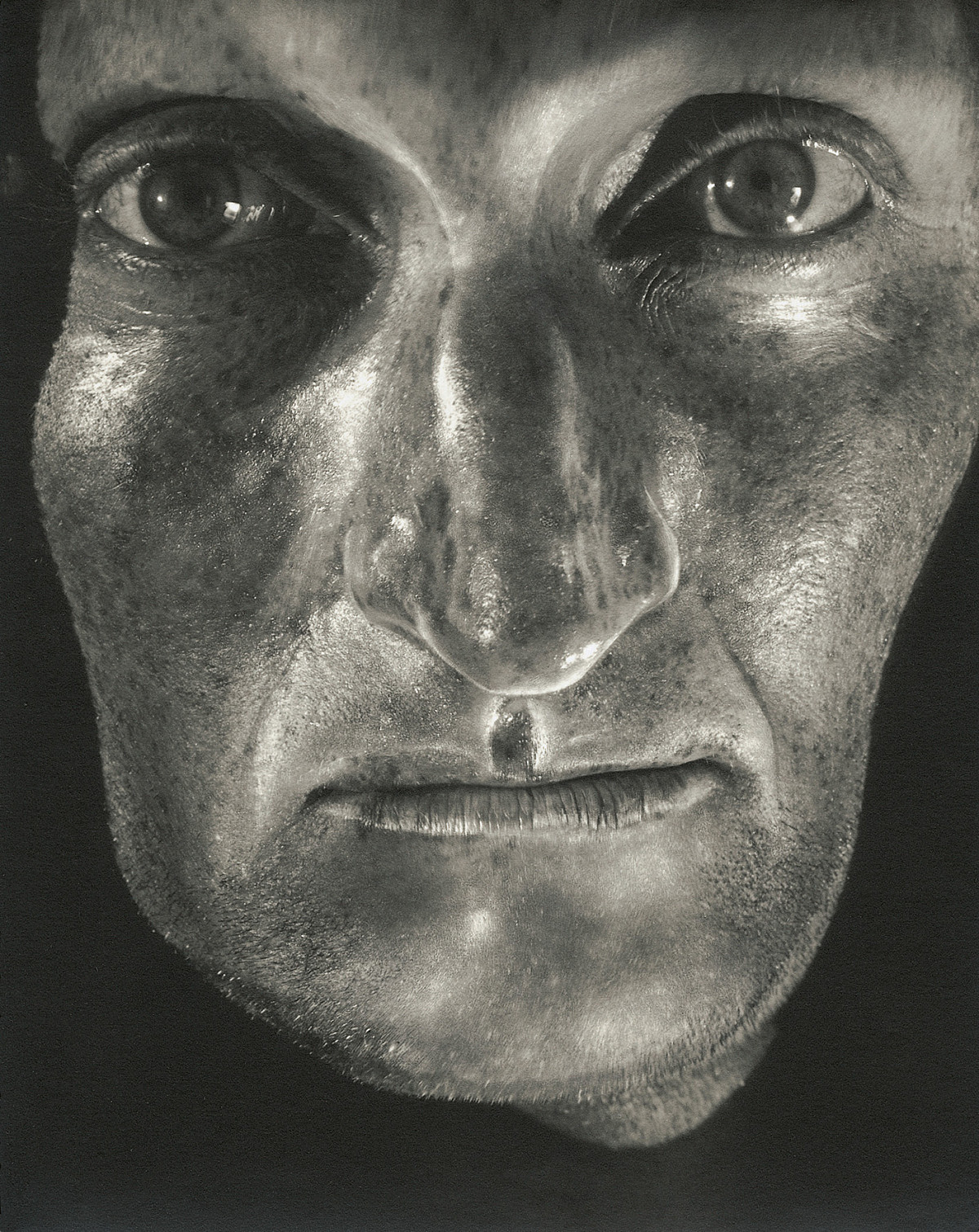

Karl Theodor Gremmler came to photography as an autodidact in 1932. He had actually trained as an advertising salesman. After becoming self-employed as a photographer, he published regularly in magazines such as Die Form, Gebrauchsgraphik, Nordsee Magazin and Atlantis. Gremmler concentrated mainly on industrial and advertising photography. In 1936 he published his first photobook, Tagewerk und Feierabend der schaffenden deutschen Frau. In the following year, Gremmler had a solo exhibition at the Oldenburgisches Landesmuseum and Museum Folkwang in Essen. He was then appointed a member of the Gesellschaft Deutscher Lichtbildner (G.D.L.). In 1939, Hans A. Keune’s publishing house, which specialised in the fishing industry, published the illustrated book Männer am Netz. This worked marked the high point of Gremmler’s career. In 1938, he acquired the studio of commercial photographer Hein Gorny, located on Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm. This studio had once been home to Lotte Jacobi, who was forced to emigrate in 1935 because of her Jewish background. When Gorny’s emigration failed to protect his Jewish wife, Ruth Lessing, he and Gremmler entered into the studio partnership “Fotografie Gremmler-Gorny. Atelier für moderne Fotografie”. In 1940 Gremmler was called up for military service and trained as a tank gunner. During a troop transport to Russia in the following year, he had a fatal accident near Heydebreck in Upper Silesia (Kędzierzyn). Quoted from Städel Museum