images that haunt us

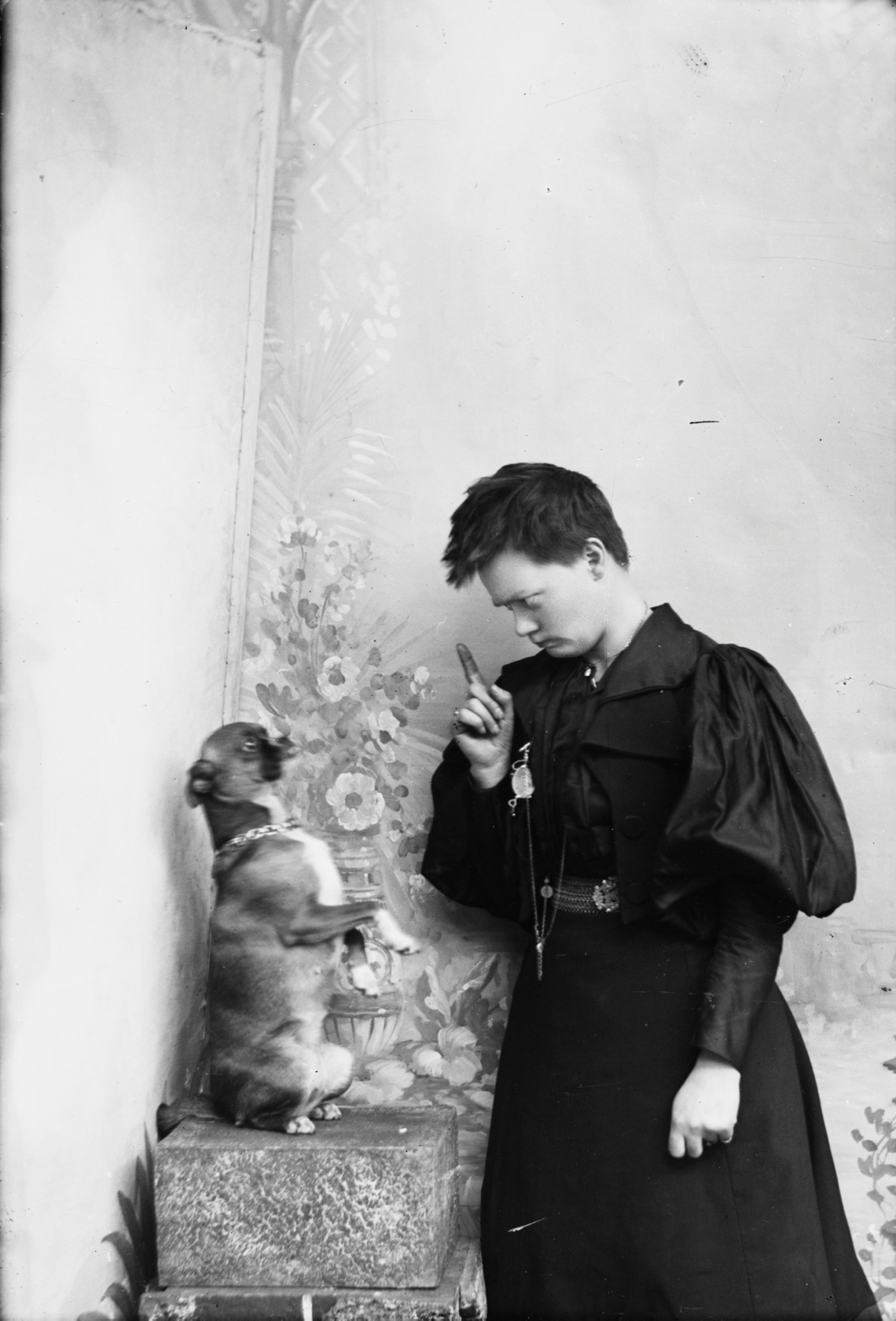

In a box marked “private”, an amazing collection of glass plates were found 30 years ago, amongst the remnants of the two portrait photographers Marie Høeg (1866-1949) and Bolette Berg (1872-1944).

In 1895, they established the Berg & Høeg photography studio in Horten, Norway, where they took portraits and views of Horten and surroundings and lived on the proceeds from sales. At that time, photography was seen as a decent and acceptable profession for women, as it was a profession that demanded a certain amount of aesthetic sense – as part of the female nature.

Horten was a naval base with the main shipyard for the Norwegian navy and had a strong flow of people who needed photographs for celebration and recollection. Perhaps that is how the two photographers understood by the very process of portraiture how important it is to stage oneself and to what a large degree that contributes to how we are perceived.

The Preus museum collection has 440 glass negatives from Berg & Høeg. Among the cartons in the 1980s were discovered some on which had been written “private.” It is not unusual that photographers also have private photographs in their archives. But these were not ordinary keepsake pictures. They indicate that the two photographers, especially Marie Høeg, experimented with various gender roles.

Imagine the fun they must have had, cross-dressing and playing! At the same time, the images are deeply serious, as they reflect upon the expectations and attitudes towards women, and their lack of rights and freedom. We know that Høeg was the extrovert and started groups to fight for women’s rights. Bolette Berg was less in the public view. However, she must have been back of the camera in many of these photographs, which have attracted international notice.

We find several such boundary-breaking photographic projects in Europe and America around 1900. They correspond with women’s battle for full civil rights and the right to define their own identity. So these photographs are a part of an international history – or herstory – that has meaning and recognition value for all women, including now.

All images are digital reproductions of the original glass plates. Some of the plates have cracks and damages, left visible in the reproductions.

All images and text retrieved from The Preus museum on Flickr

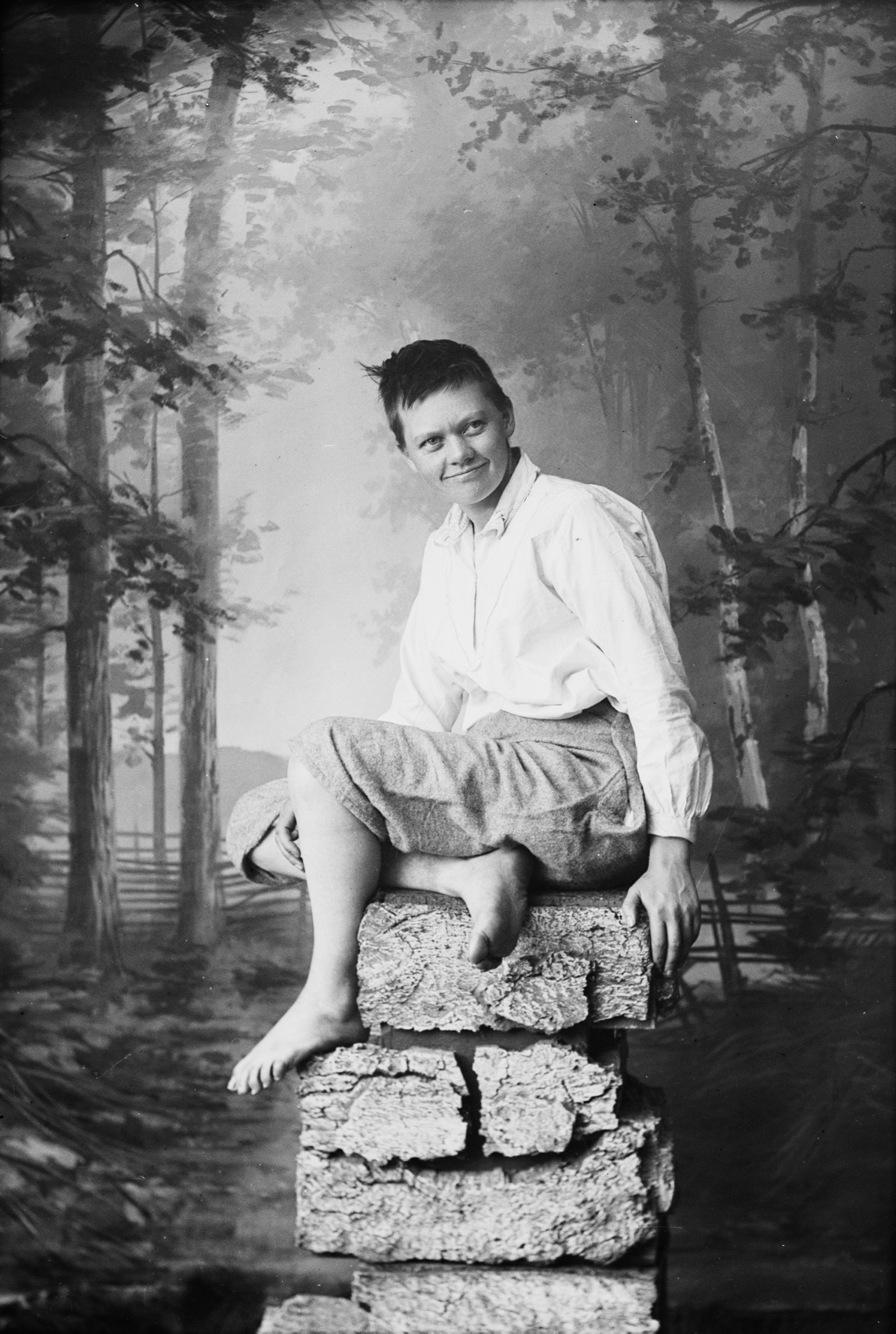

In a box marked “private”, an amazing collection of glassplates were found 30 years ago, amongst the remnants of the two portrait photographers Marie Høeg (1866-1949) and Bolette Berg (1872-1944).

In 1895, they established the Berg & Høeg photography studio in Horten, Norway, where they took portraits and views of Horten and surroundings and lived on the proceeds from sales. At that time, photography was seen as a decent and acceptable profession for women, as it was a profession that demanded a certain amount of aesthetic sense – as part of the female nature.

Horten was a naval base with the main shipyard for the Norwegian navy and had a strong flow of people who needed photographs for celebration and recollection. Perhaps that is how the two photographers understood by the very process of portraiture how important it is to stage oneself and to what a large degree that contributes to how we are perceived.

The Preus museum collection has 440 glass negatives from Berg & Høeg. Among the cartons in the 1980s were discovered some on which had been written “private.” It is not unusual that photographers also have private photographs in their archives. But these were not ordinary keepsake pictures. They indicate that the two photographers, especially Marie Høeg, experimented with various gender roles.

Imagine the fun they must have had, cross-dressing and playing! At the same time, the images are deeply serious, as they reflect upon the expectations and attitudes towards women, and their lack of rights and freedom. We know that Høeg was the extrovert and started groups to fight for women’s rights. Bolette Berg was less in the public view. However, she must have been back of the camera in many of these photographs, which have attracted international notice.

We find several such boundary-breaking photographic projects in Europe and America around 1900. They correspond with women’s battle for full civil rights and the right to define their own identity. So these photographs are a part of an international history – or herstory – that has meaning and recognition value for all women, including now.

All images are digital reproductions of the original glass plates. Some of the plates have cracks and damages, left visible in the reproductions.

All images and text retrieved from The Preus museum on Flickr

In a box marked “private”, an amazing collection of glass plates were found 30 years ago, amongst the remnants of the two portrait photographers Marie Høeg (1866-1949) and Bolette Berg (1872-1944).

In 1895, they established the Berg & Høeg photography studio in Horten, Norway, where they took portraits and views of Horten and surroundings and lived on the proceeds from sales. At that time, photography was seen as a decent and acceptable profession for women, as it was a profession that demanded a certain amount of aesthetic sense – as part of the female nature.

Horten was a naval base with the main shipyard for the Norwegian navy and had a strong flow of people who needed photographs for celebration and recollection. Perhaps that is how the two photographers understood by the very process of portraiture how important it is to stage oneself and to what a large degree that contributes to how we are perceived.

The Preus museum collection has 440 glass negatives from Berg & Høeg. Among the cartons in the 1980s were discovered some on which had been written “private.” It is not unusual that photographers also have private photographs in their archives. But these were not ordinary keepsake pictures. They indicate that the two photographers, especially Marie Høeg, experimented with various gender roles.

Imagine the fun they must have had, cross-dressing and playing! At the same time, the images are deeply serious, as they reflect upon the expectations and attitudes towards women, and their lack of rights and freedom. We know that Høeg was the extrovert and started groups to fight for women’s rights. Bolette Berg was less in the public view. However, she must have been back of the camera in many of these photographs, which have attracted international notice.

We find several such boundary-breaking photographic projects in Europe and America around 1900. They correspond with women’s battle for full civil rights and the right to define their own identity. So these photographs are a part of an international history – or herstory – that has meaning and recognition value for all women, including now.

All images are digital reproductions of the original glass plates. Some of the plates have cracks and damages, left visible in the reproductions. (quoted from the Album description)

All images from this post were retrieved from The Preus museum collection hosted on Flickr. Link to album (x)

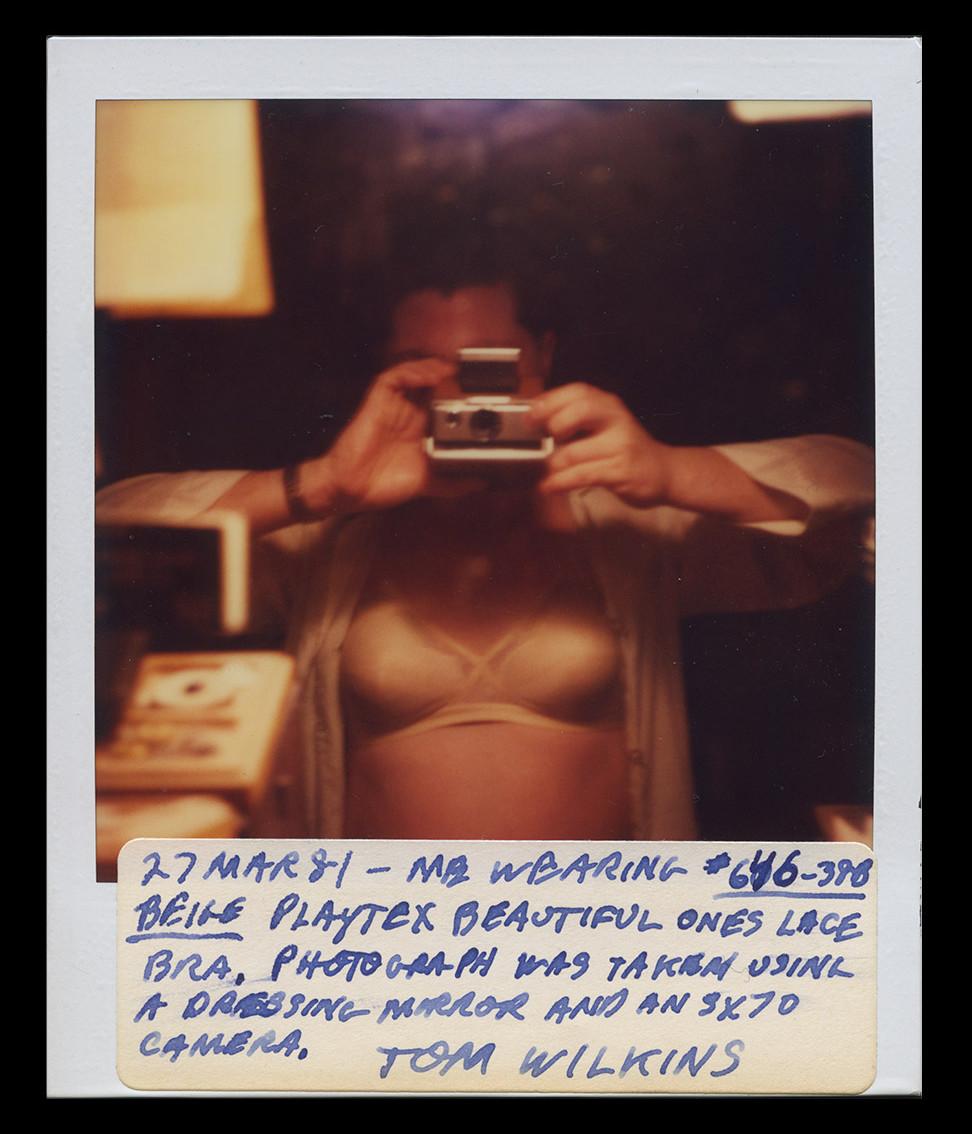

Courtesy Christian Berst Art Brut : Qui est Tom Wilkins ? C’est la question à laquelle Sébastien Girard essaie de répondre depuis 2011, date à laquelle il fait l’acquisition de 900 Polaroïds énigmatiques, édités en 2017 sous le nom My TV Girls. Cette série de captations télévisuelles légendées par son auteur met en scène des femmes et se termine par le seul et unique autoportrait de la série où Tom Wilkins, se représente en femme. | src ODLP ~ l’œil de la photographie

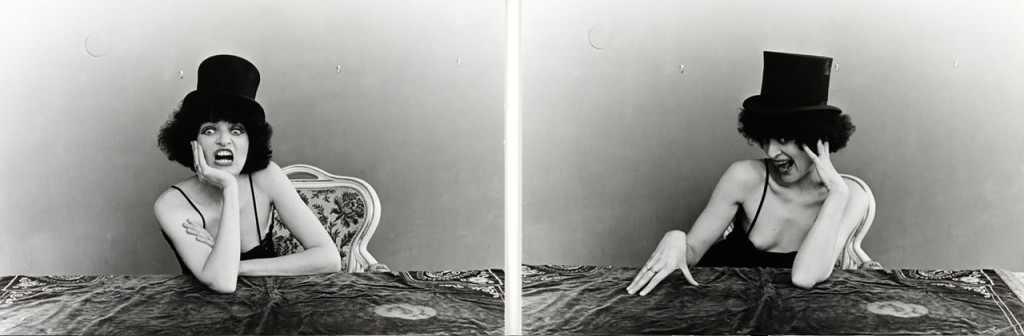

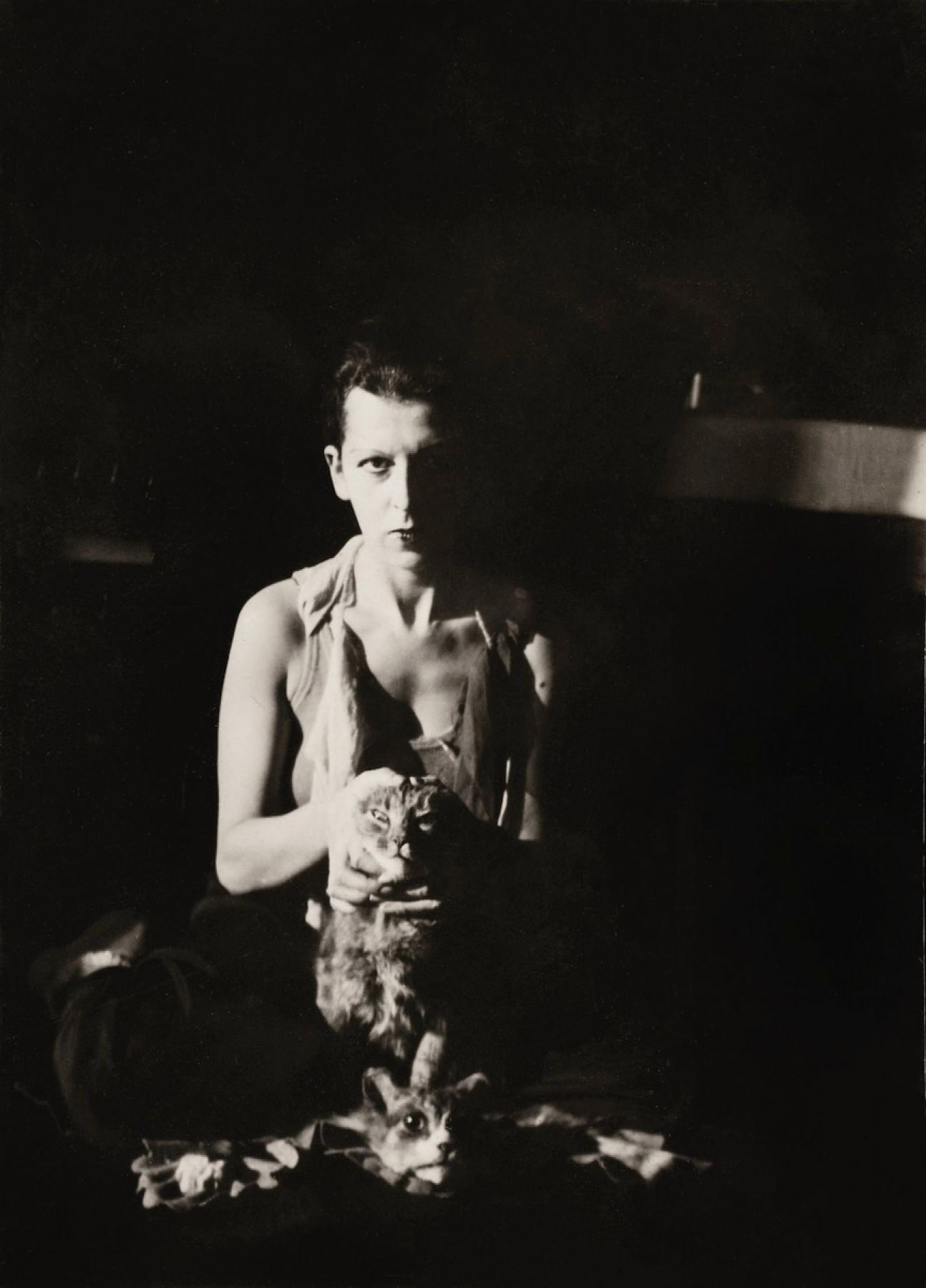

“Lucy and Kid”. Nantes, ca.1926. Original silver print. This piece seems to close the series of “self-portraits with a glass globe” (1926), which initiates complex manipulations, technical processes that Claude Cahun (along with Marcel Moore) will later use for photomontages (1929-1939). Note the disturbing position of the suspended cat, held above the void against a background reminiscent of the decor of an expressionist film.

“Les autoportraits ont beaucoup contribué à la reconnaissance puis à l’engouement posthumes dont l’œuvre de Claude Cahun [et marcel Moore] fut l’objet. Dans un décor généralement réduit au minimum (un fond de mur, de tissu, un coin de jardin, l’angle d’une porte), avec peu d’accessoire, mais choisis pour leur qualité symbolique (…), Claude Cahun va multiplier les poses, les travestissements, les rôles, les mises à nu, pour aboutir à une sorte de chorégraphie immobile de mouvement sériel, où transparaît son attention pour la danse, la danse qui semble combiner et sublimer tous les genres. Elle ne se borne pas à questionner une identité problématique, elle la force, elle la produit. L’appareil photographique est véritablement placé dans la position d’un « miroir magique », que l’on scrute et interpelle, d’un instrument qui, paradoxalement, doit induire une transformation.”

(Catalogue exposition Claude Cahun, Jeu de Paume, Paris, Hazan, 2011, p. 64)

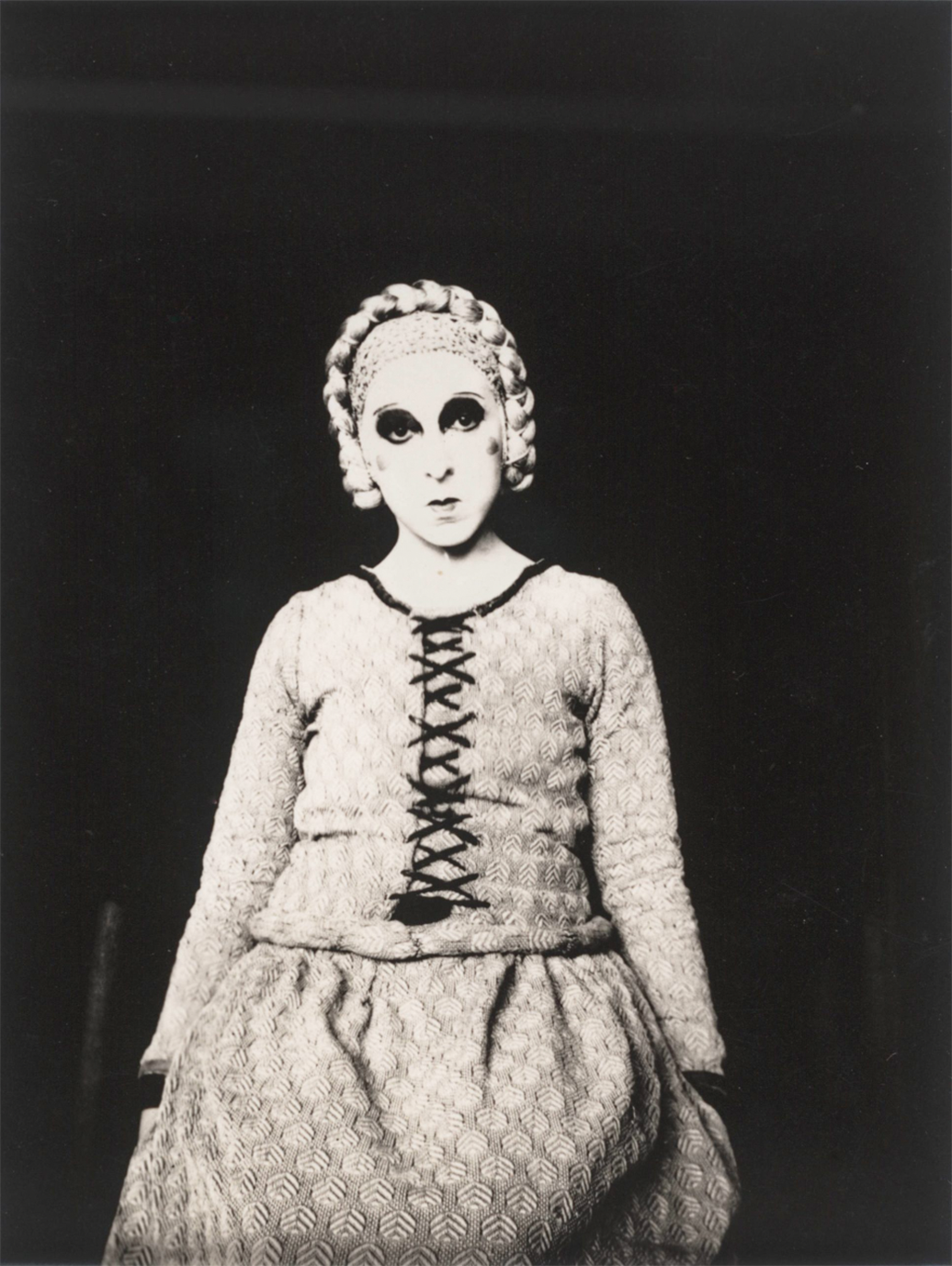

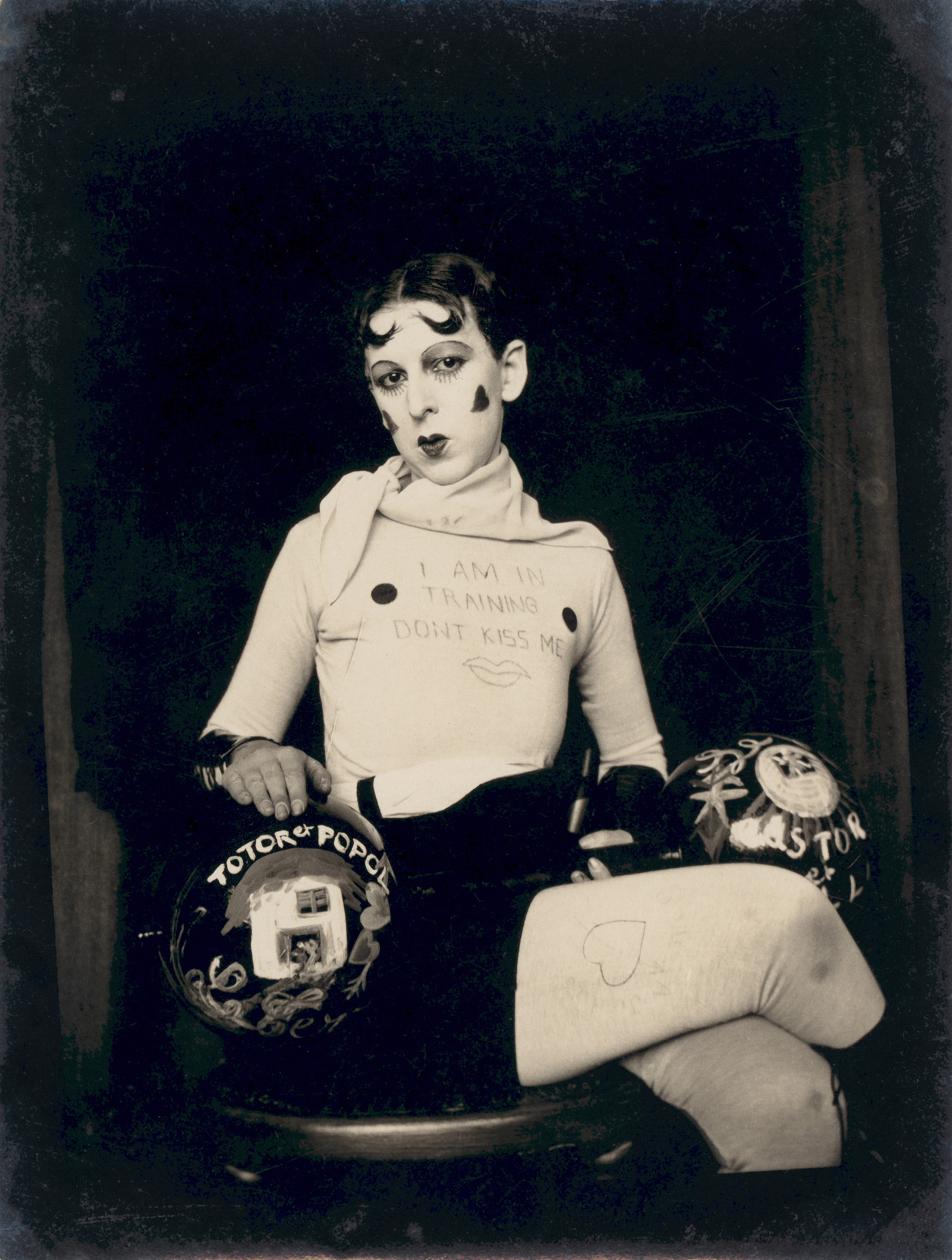

“The Self-portraits have contributed a great deal to the recognition and then to the posthumous enthusiasm for Claude Cahun’s [and Marcel Moore’s] work. In a decor generally kept to a minimum (a wall background, fabric, a corner of the garden, the angle of a door), with few accessories, chosen for their symbolic quality (…), Claude Cahun will multiply the poses, the disguises, the roles, the stripping, to end up with a kind of motionless choreography of serial movements, where the emphasis on dance shines through, the dance that seems to combine and sublimate all genres. They do not limit themselves to questioning a problematic identity, they force it, they produce it. The camera is truly placed in the position of a « miroir magique », which one scrutinizes and questions, an instrument which, paradoxically, must induce a transformation.” (*)

(Catalogue of the exposition Claude Cahun at Jeu de Paume, Paris, Hazan, 2011, p. 64)

(*) The modification of pronouns is completely our choice

![Claude Cahun :: Untitled [Claude Cahun as The Devil in Le Mystère d'Adam (The Mystery of Adam)], 1929.](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/img_0836-1.jpg)

![Claude Cahun - Marcel Moore :: Untitled [Claude Cahun in Le Mystère d'Adam (The Mystery of Adam)], 1929. © Estate of Claude Cahun. | src SF·MoMA](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/claude-cahun-untitled-claude-cahun-in-le-mystere-dadam-the-mystery-of-adam-1929-crp.jpg)