C.C. Pierce :: Young Girls of the Hopi Nation, All Wearing the Squash Blossom Hairstyle Indicating Their Unmarried Status, Shonguapavi, Arizona, 1900 / via

related post, here

images that haunt us

C.C. Pierce :: Young Girls of the Hopi Nation, All Wearing the Squash Blossom Hairstyle Indicating Their Unmarried Status, Shonguapavi, Arizona, 1900 / via

related post, here

Juan Laurent :: Ornate Doorknocker, ca. 1870 / src: The Guardian

George Washington Wilson :: Friedrich III when the Crown Prince of Prussia and his son, Wilhelm II when Prince of Prussia, Balmoral, October 1863.

Both Friedrich and Wilhelm wear tartan kilts and Tam o’ Shanter hats.

Albumen print./ source: The Royal Coll. Trust

more [+] by this photographer

George Washington Wilson :: Stonehenge. General view from the East, 1860.

Stonehenge

with sheep in the foreground. In the centre a man stands leans against one of the stones. A cart stands on the right.

Carbon print. / source: The Royal Coll. Trust

more [+] by this photographer /

more [+] Stonehenge posts

Alphonse Le Blondel :: Untitled (Family Group in a Garden), ca. 1855 / source

Francis Orville Libby (1883–1961)

:: Winter Moonrise, undated. Multiple gum process printed in blue. source: artmuseum.princeton.edu

Thanks to

dilution and dame-de-pique for blogging and blogging it. My apologies for not reblogging but for SOME reason I cannot do it actually.

Although Moulin was sentenced in 1851 to a month in jail for producing images that, according to court papers, were “so obscene that even to pronounce the titles . . . would be to commit an indecency,” this daguerreotype seems more allied to art than to erotica. Instead of the boudoir props and provocative poses typical of hand-colored pornographic daguerreotypes, Moulin depicted these two young women utterly at ease, as unselfconscious in their nudity as Botticelli’s Venus. [quoted from The Met]

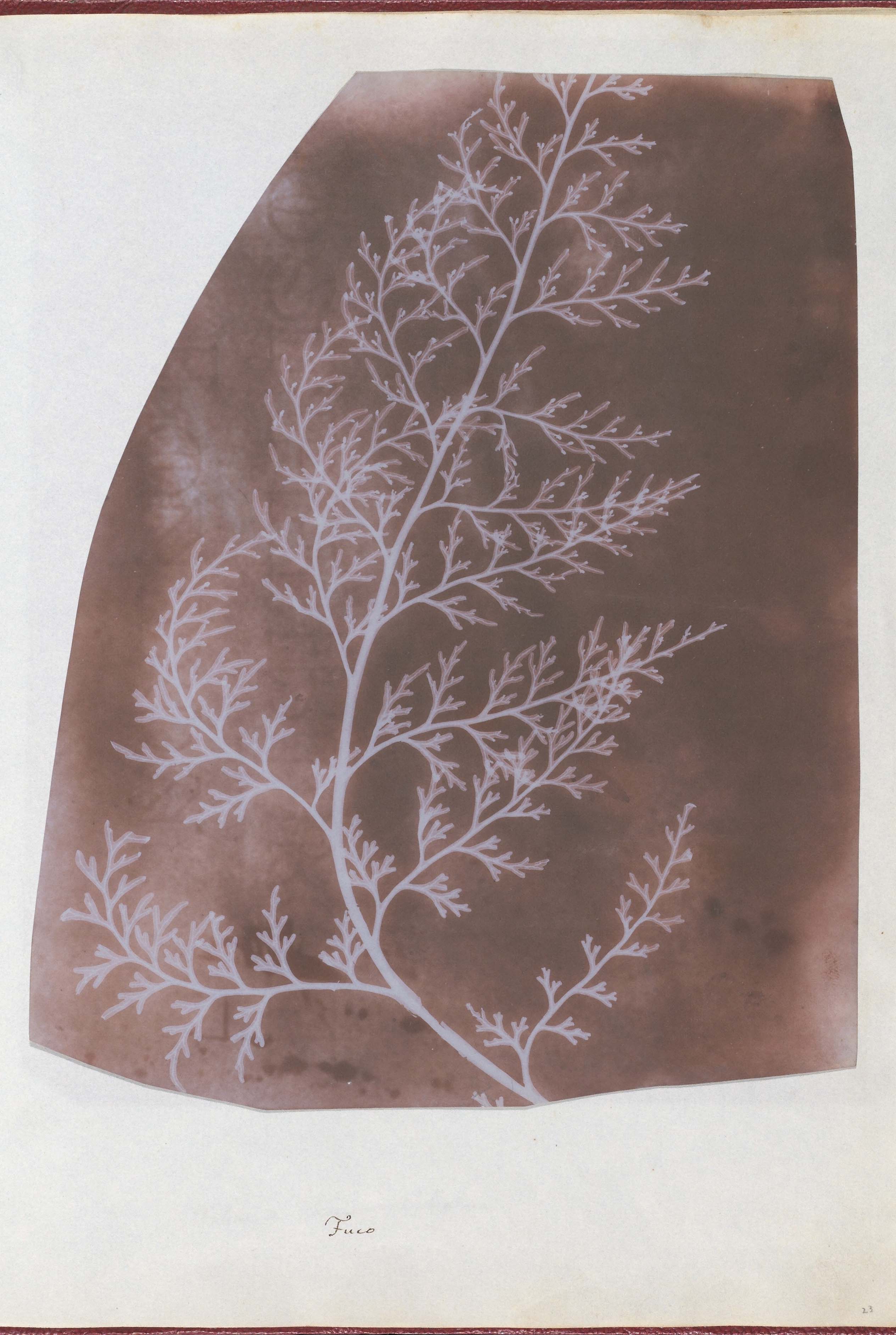

This evanescent trace of a biological specimen, among the rarest of photographs, was made by William Henry Fox Talbot just months after he first presented his invention, photography—or “photogenic drawing,” as he called it—to the public. Talbot’s earliest images were made without a camera; here a piece of slightly translucent seaweed was laid directly onto a sheet of photosensitized paper, blocking the rays of the sun from the portions it covered and leaving a light impression of its form.

Plants were often the subject of Talbot’s early photographs, for he was a serious amateur botanist and envisioned the accurate recording of specimens as an important application of his invention. The “Album di disegni fotogenici,” in which this print appears, contains thirty-six images sent by Talbot to the Italian botanist Antonio Bertoloni in 1839–40. It was the first important photographic work purchased by the Metropolitan Museum. [quoted from source]

This experimental proof is a fine example of the capacity of Talbot’s “photoglyphic engraving” to produce photographic results that could be printed on a press, using printer’s ink-a more permanent process than photographs made with light and chemicals. Like Talbot’s earliest photographic examples, the image here was photographically transferred to the copper engraving plate by laying the seeds directly on the photosensitized plate and exposing it to light, without the aid of a camera. Equally reminiscent of Talbot’s early experiments, this image is part of Talbot’s lifelong effort to apply his various photographic inventions to the field of botany. In a letter tipped into the Bertoloni Album, Talbot wrote, “Je crois que ce nouvel art de mon invention sera d’un grand secours aux Botanistes” (“I think that my newly invented art will be a great help to botanists”). Such uses were still prominent in Talbot’s thinking years later when developing his photogravure process; he noted in 1863 that “if this art [of photoglyphic engraving] had been invented a hundred years ago, it would have been very useful during the infancy of botany.” Had early botanists been able to print fifty copies of each engraving, he continued, and had they sent them to distant colleagues, “it would have greatly aided modern botanists in determining the plants intended by those authors, whose descriptions are frequently so incorrect that they are like so many enigmas, and have proved a hindrance and not an advantage to science.” [quoted from The Met]