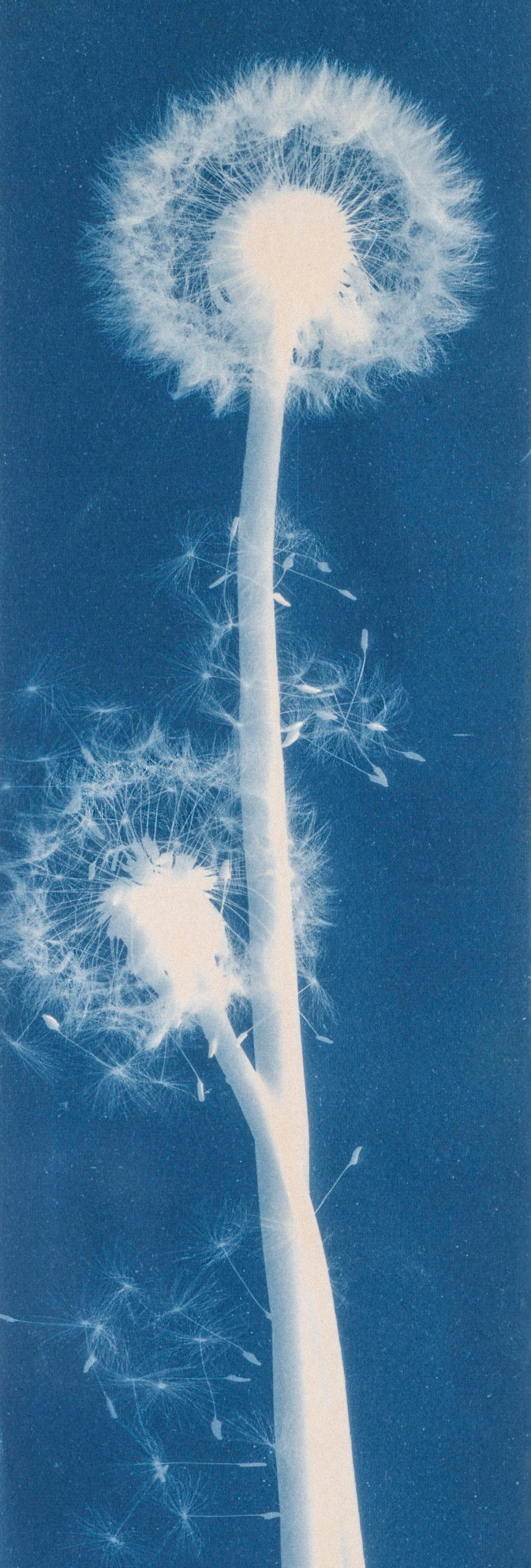

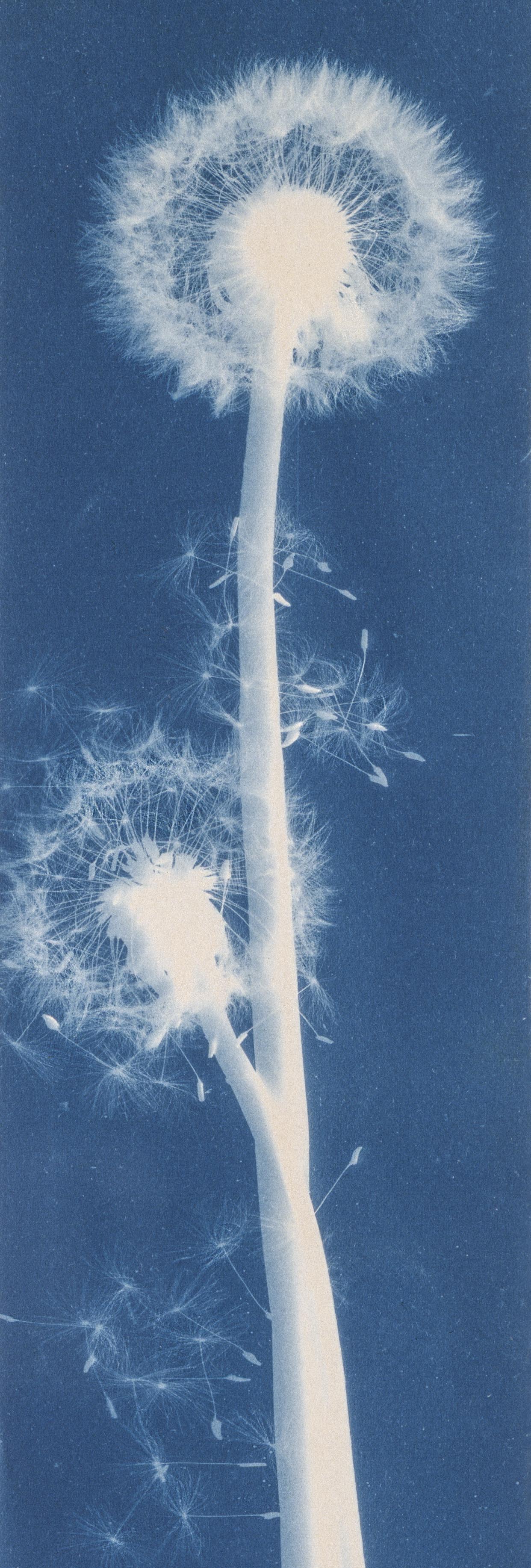

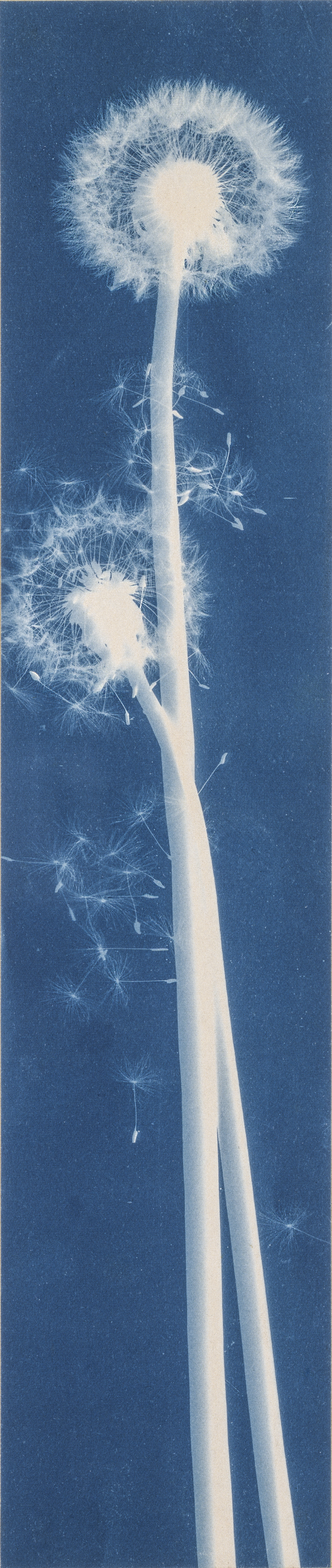

Jaques was already a respected printmaker when she began making cyanotype photograms of wildflowers. An active member of the Wild Flower Preservation Society, she created over a thousand of these botanical images. [See Dandelion Seeds, Taraxacium Officinale, SAAM, 1994.91.89] Made without a camera by placing objects directly on sensitized paper and exposing it to light, the photogram is the least industrialized type of photography. Because prints were easy to produce by this method, it achieved wide popularity. Graphic artists often chose this form of print because of its rich Prussian blue color. Aligned with the antimodernist views of the late Victorian Arts and Crafts movement, Jaques’s work reflects a reverence for commonplace elements of nature and the beautifully crafted object.

Merry A. Foresta American Photographs: The First Century (Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art with the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996). From Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM)