images that haunt us

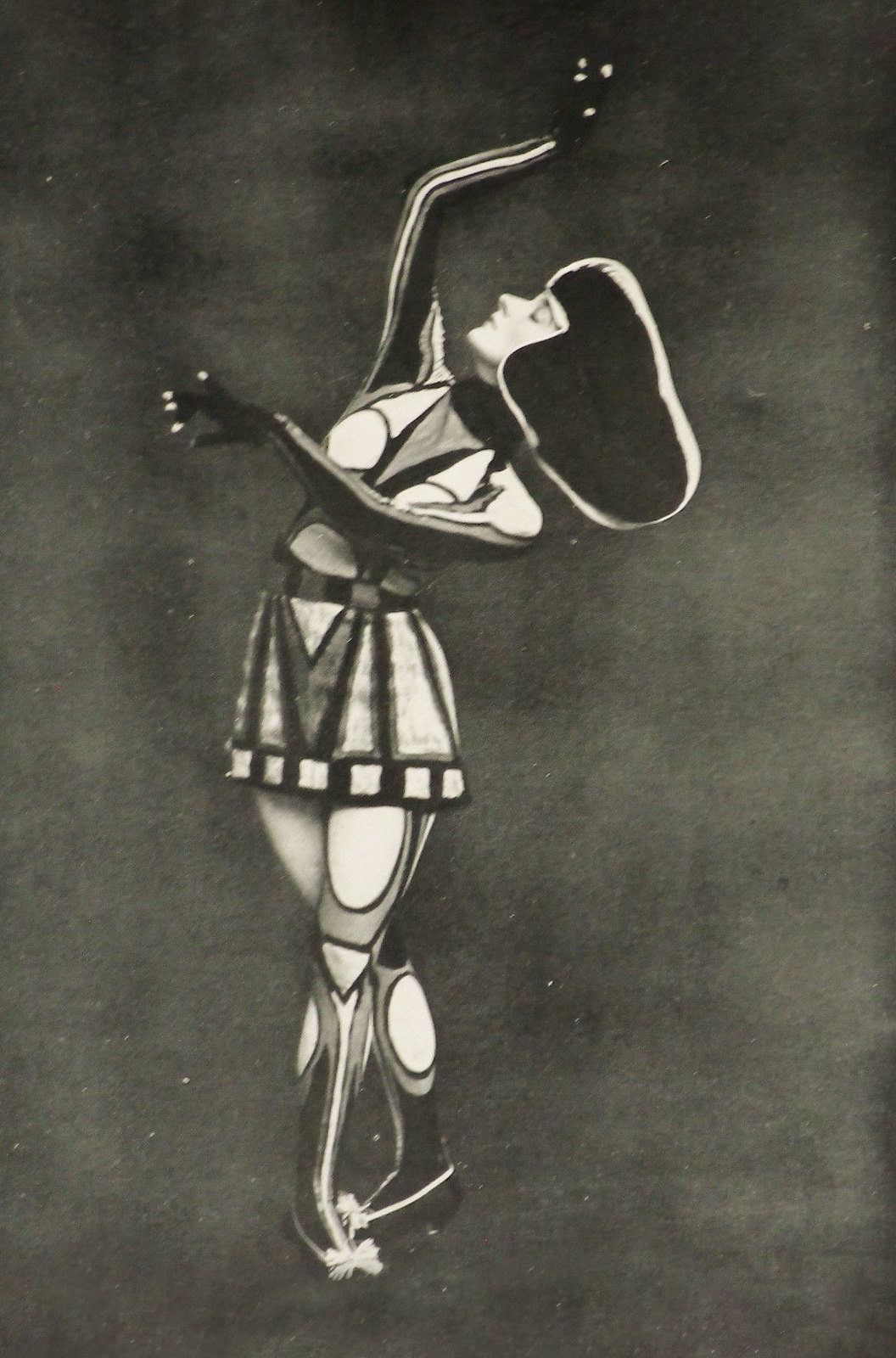

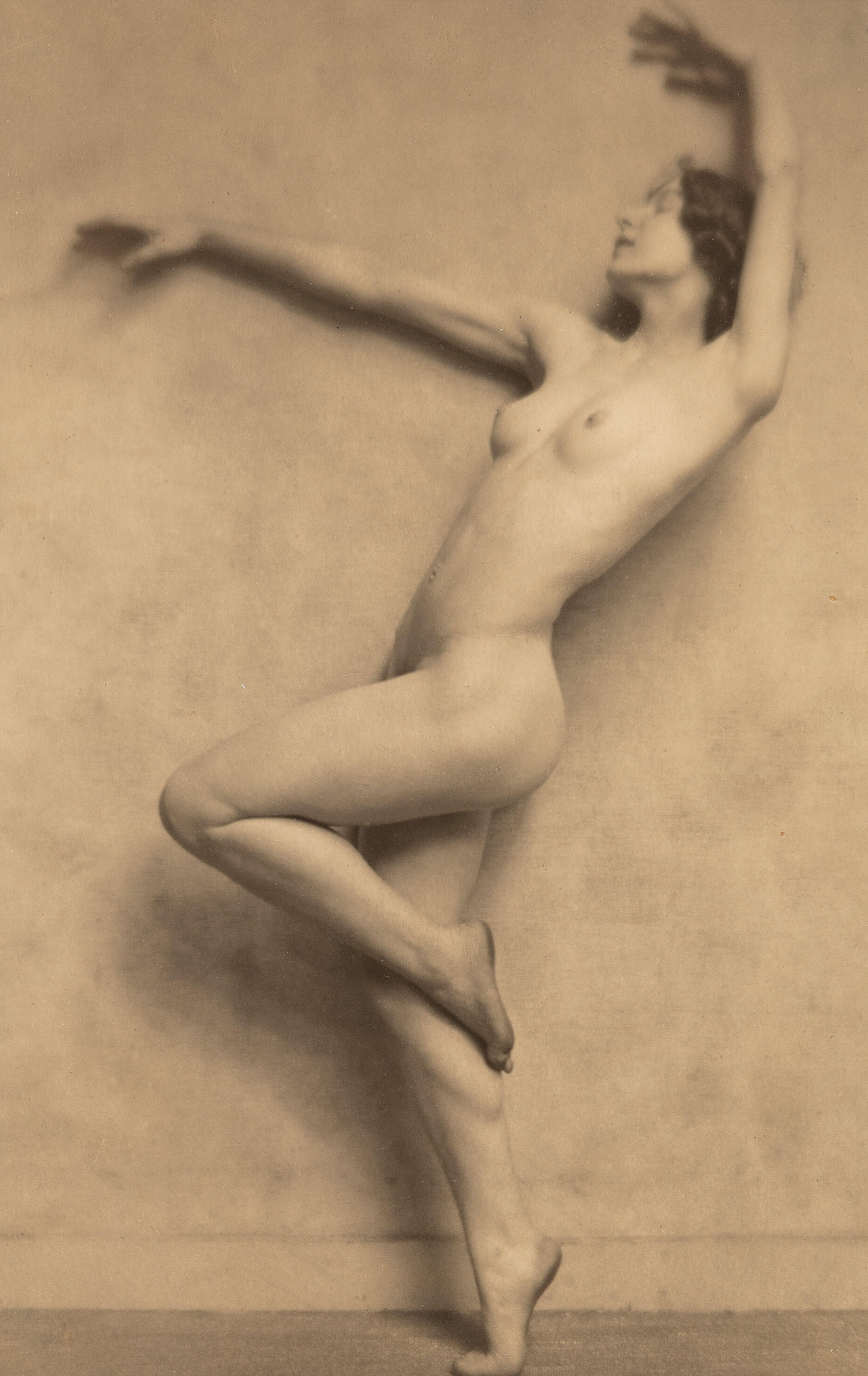

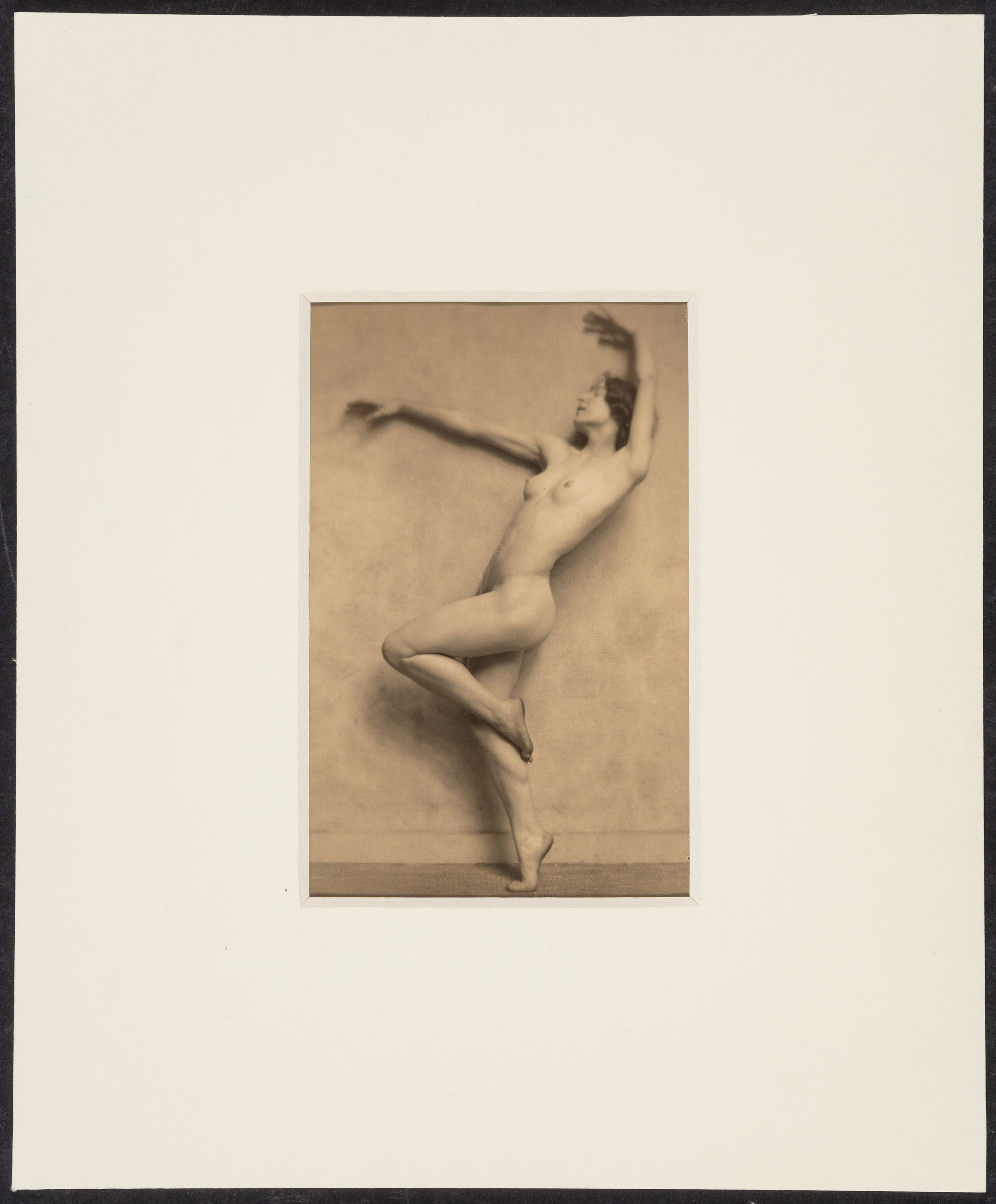

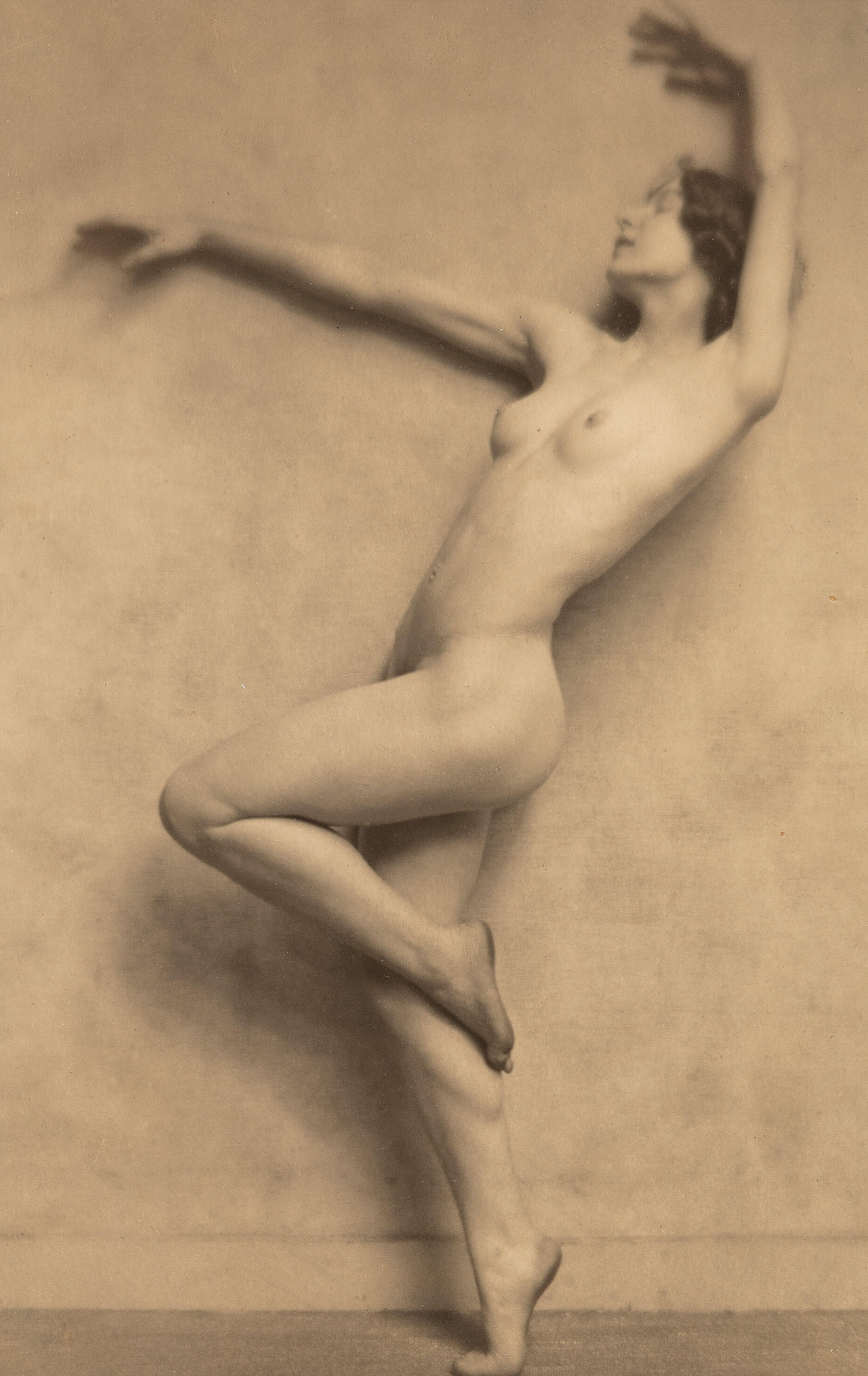

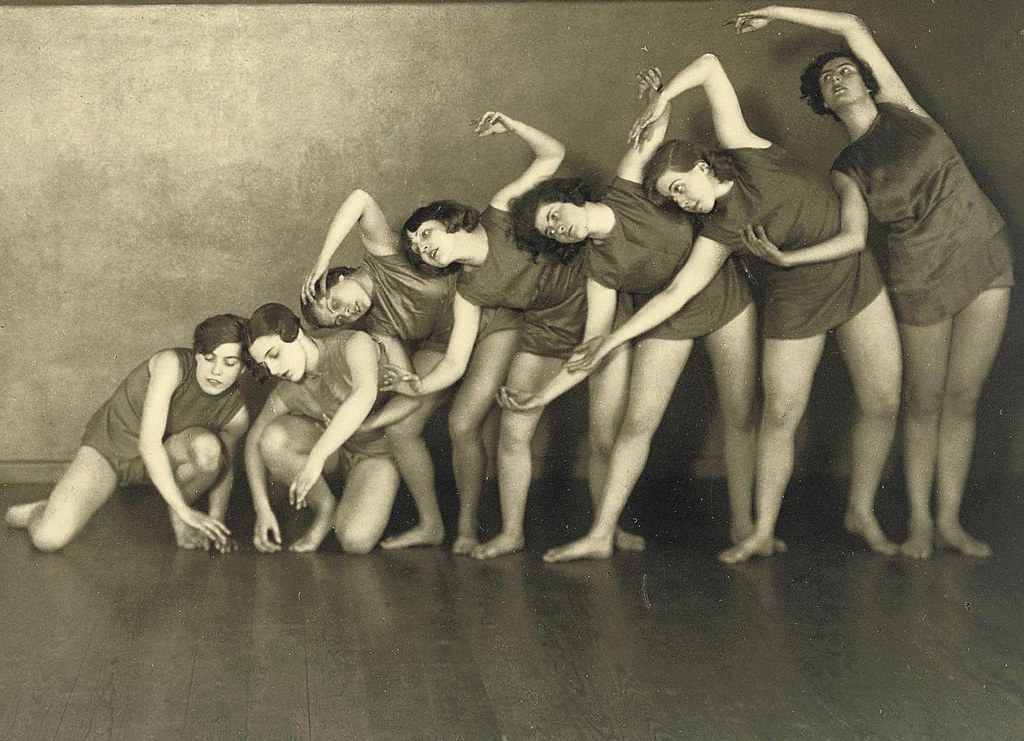

Aerodanze 4: Pubblicata in Vaccarino E., (a cura di) Giannina Censi: danzare il futurismo. Milano: Electa; Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, 1998, p.102; Bonfanti E., Il corpo intelligente. Torino: il segnalibro, 1995, p.27; G. Lista, Cinema e fotografia futurista. cat. della mostra (Rovereto, Archivio del ‘900, 18 maggio – 15 luglio 2001) Milano: Skira editore, 2001, p. 211; E. Martera, P. Pietrogrande (a cura di), Il mito della velocità : arte, motori e società nell’Italia del ‘900: Firenze ; Milano : Giunti, 2008, p. 117

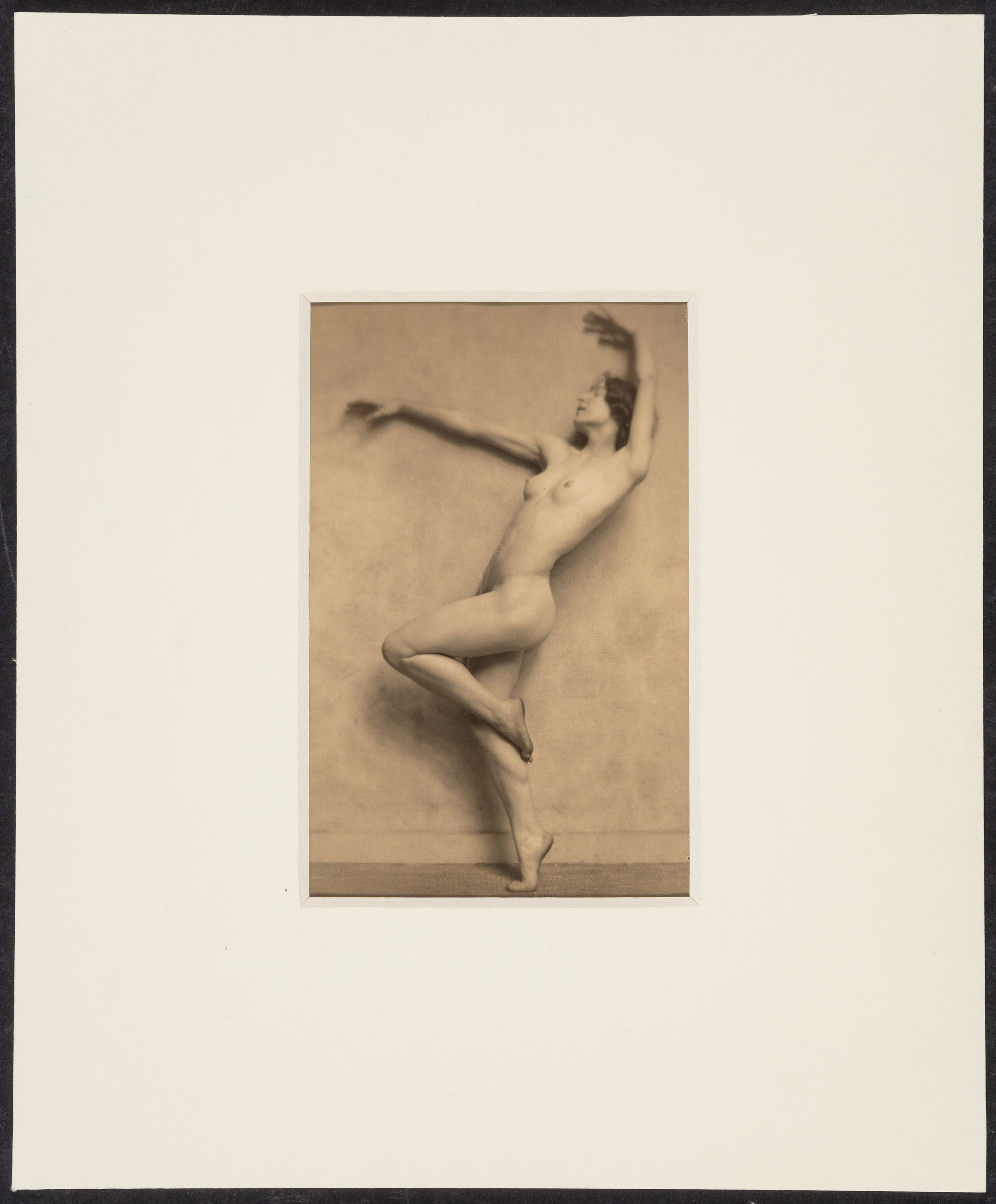

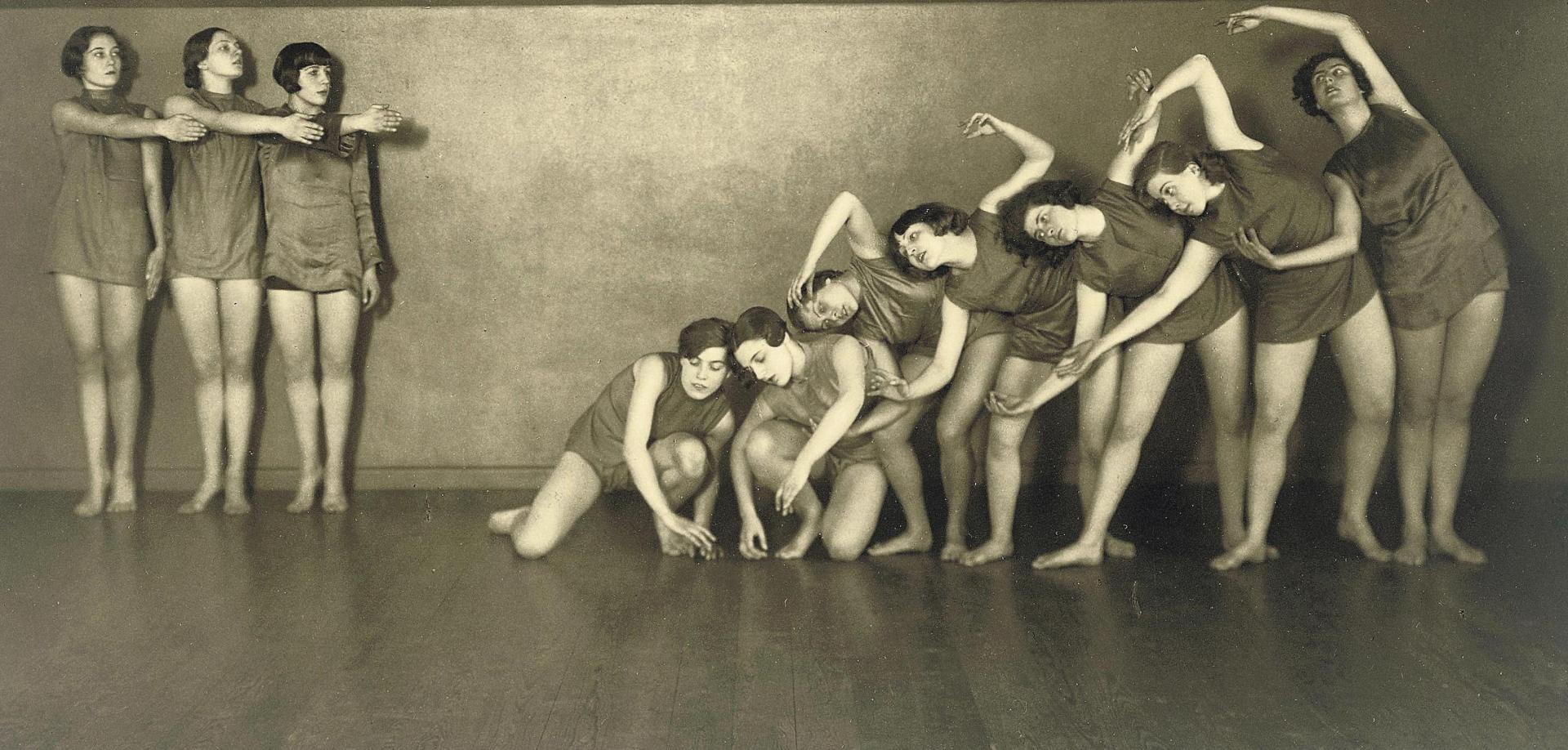

Aerodanze 5: Pubblicata in Bonfanti E., Il corpo intelligente. Torino: il segnalibro, 1995, p.27; Vaccarino E.,(a cura di) Giannina Censi: danzare il futurismo. Milano: Electa; Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, 1998, p.106; G. Lista, Cinema e fotografia futurista. cat. della mostra (Rovereto, Archivio del ‘900, 18 maggio – 15 luglio 2001) Milano: Skira editore, 2001, p. 211; E. Martera, P. Pietrogrande (a cura di), Il mito della velocità : arte, motori e società nell’Italia del ‘900: Firenze ; Milano : Giunti, 2008, p. 117; Belli G. (a cura di), Sprachen des Futurismus, cat. della mostra (Berlino, Martin Gropius Bau, 2 ottobre 2009- 11 gennaio 2010), Berlin: Berliner Festspiele, 2009, p. 236; Adrien Sina, «Feminine futures. Valentine de Saint-Point. Performance, Danse, Guerre, Politique et érotisme», Les Presses du réel, 2011, p.230; Macel C., Lavigne E. (a cura di) Danser sa vie : art et danse de 1900 à nos jour. Paris : Centre Georges Pompidou, 2011, p.114; Greene V.(a cura di), Italian Futurismus 1909-1944 : Reconstructing the Universe. cat. della mostra (New York, Guggenheim Museum, 21 febbraio-1 settembre 2014) Solomon R.Guggenheim Foundation 2014, p. 306

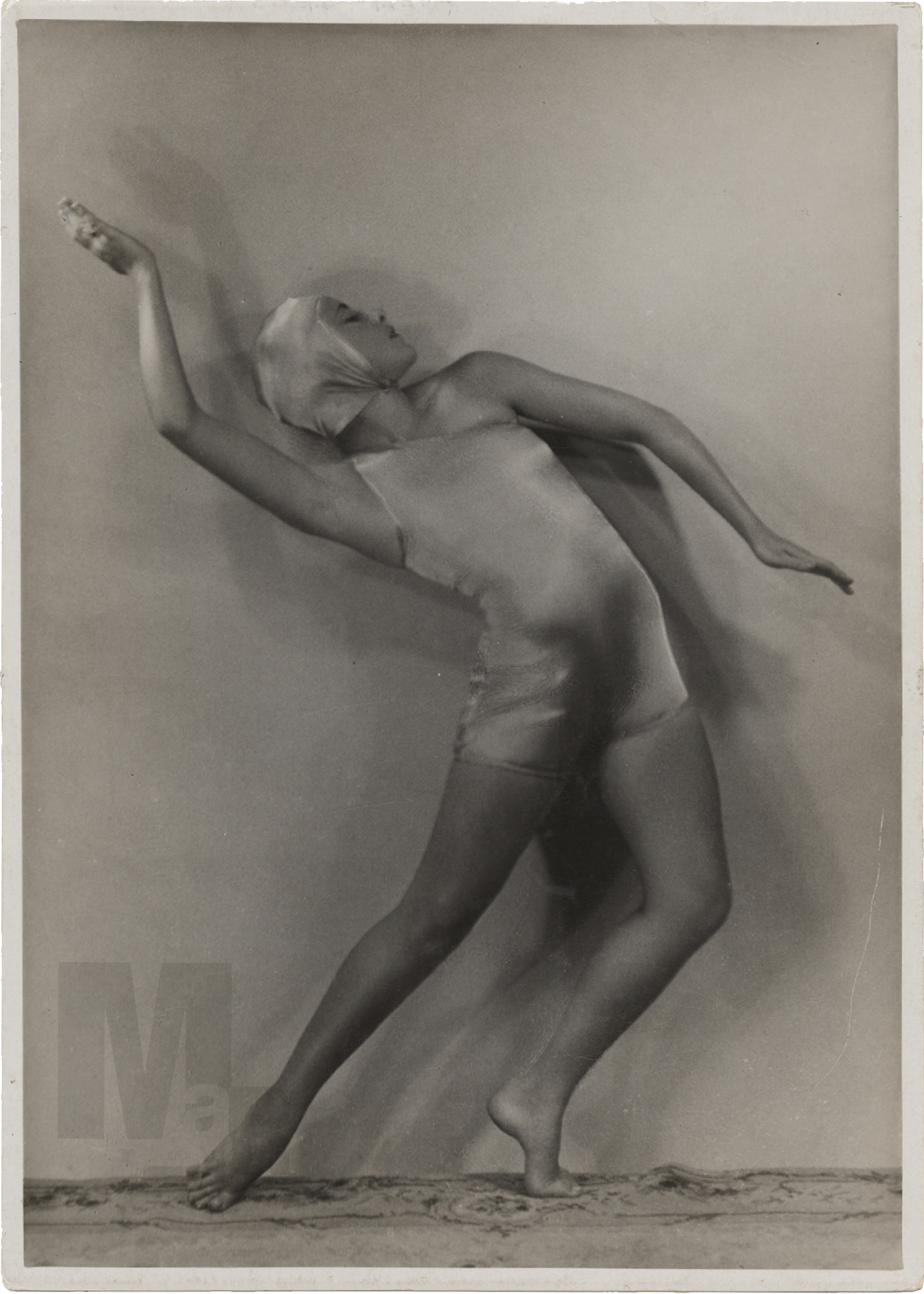

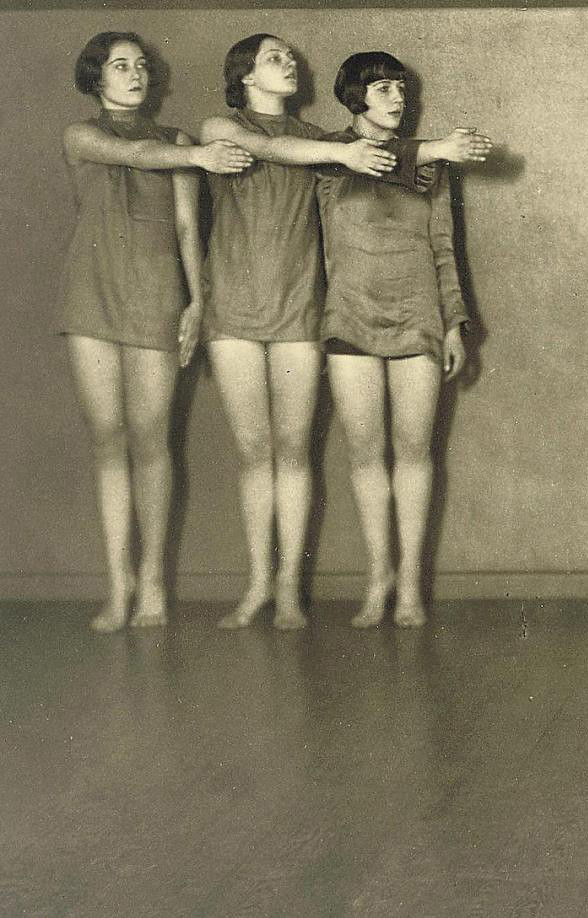

Aerodanze 6: Pubblicata in Vaccarino E., (a cura di) Giannina Censi: danzare il futurismo. Milano: Electa; Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, 1998, p.105; G. Lista, Cinema e fotografia futurista. cat. della mostra (Rovereto, Archivio del ‘900, 18 maggio – 15 luglio 2001) Milano: Skira editore, 2001, p. 211; E. Martera, P. Pietrogrande (a cura di), Il mito della velocità : arte, motori e società nell’Italia del ‘900: Firenze ; Milano : Giunti, 2008, p. 117; Belli G.(a cura di), Sprachen des Futurismus, cat. della mostra (Berlino, Martin Gropius Bau, 2 ottobre 2009- 11 gennaio 2010), Berlin: Berliner Festspiele, 2009, p. 237; Adrien Sina, «Feminine futures. Valentine de Saint-Point. Performance, Danse, Guerre, Politique et érotisme», Les Presses du réel, 2011, p.230. Esposta alla mostra Danser sa vie. Art et danse de 1900 à nos jour, a cura di Macel C., Lavigne E., Paris : Centre Georges Pompidou, 2011; Greene V.(a cura di), Italian Futurismus 1909-1944 : Reconstructing the Universe. cat. della mostra (New York, Guggenheim Museum, 21 febbraio-1 settembre 2014) Solomon R.Guggenheim Foundation, 2014, p. 226

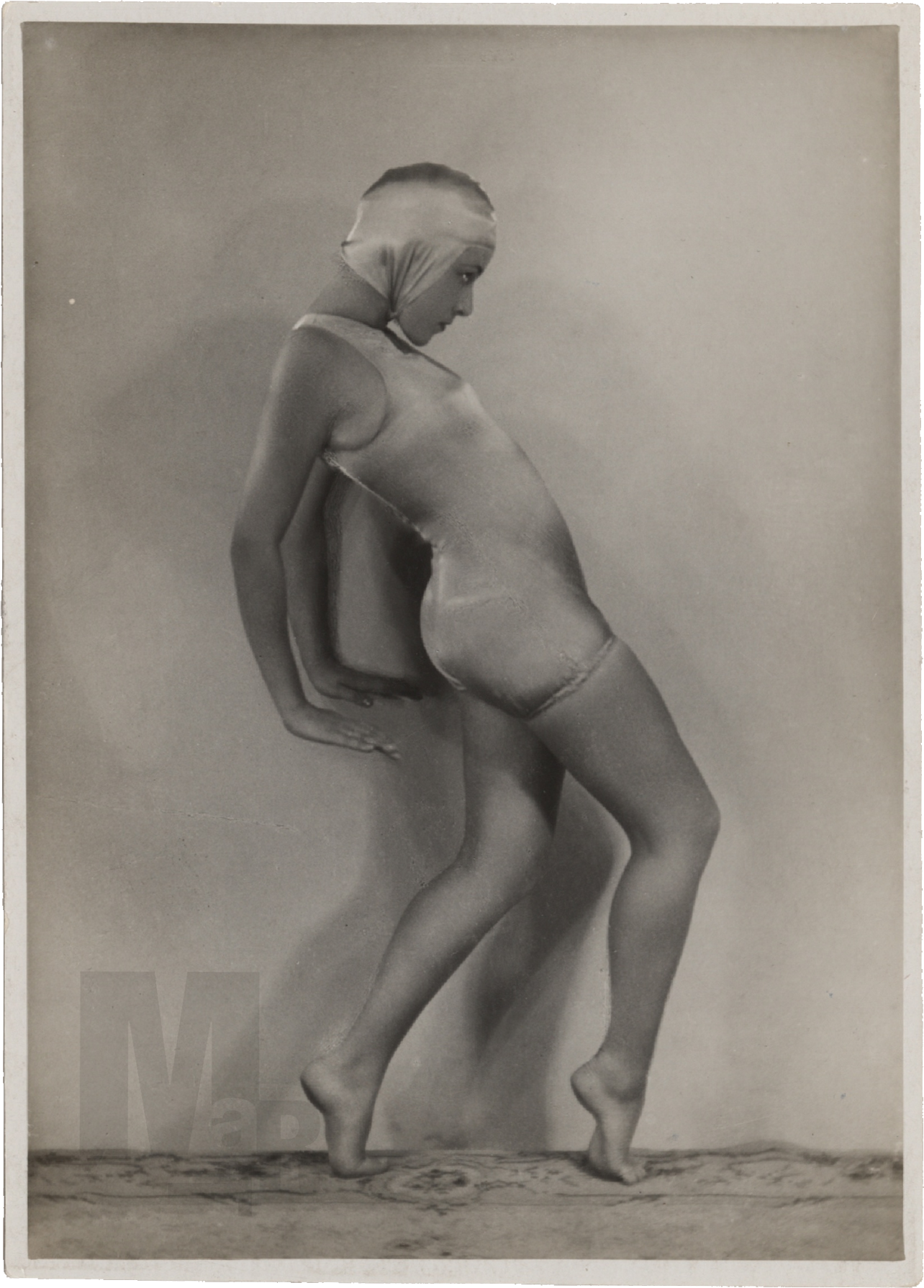

Aerodanze 7: Pubblicata in Bonfanti E., Il corpo intelligente. Torino: il segnalibro, 1995, p.28; Vaccarino E., (a cura di) Giannina Censi: danzare il futurismo. Milano: Electa; Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, 1998, p.101; G. Lista, Cinema e fotografia futurista. cat. della mostra (Rovereto, Archivio del ‘900, 18 maggio – 15 luglio 2001) Milano: Skira editore, 2001, p. 212; E. Martera, P. Pietrogrande (a cura di), Il mito della velocità : arte, motori e società nell’Italia del ‘900, cat. della mostra (Roma, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, 19 febbraio – 18 maggio 2008) Giunti, 2008, p. 117; Belli G. (a cura di), Sprachen des Futurismus, cat. della mostra (Berlino, Martin Gropius Bau, 2 ottobre 2009- 11 gennaio 2010), Berlin: Berliner Festspiele, 2009, p. 236; Adrien Sina, «Feminine futures. Valentine de Saint-Point. Performance, Danse, Guerre, Politique et érotisme», Les Presses du réel, 2011, p.231; Macel C., Lavigne E. (a cura di) Danser sa vie : art et danse de 1900 à nos jour. Paris : Centre Georges Pompidou, 2011, p. 114; Greene V.(a cura di), Italian Futurismus 1909-1944 : Reconstructing the Universe. cat. della mostra (New York, Guggenheim Museum, 21 febbraio-1 settembre 2014) Solomon R.Guggenheim Foundation, 2014, p. 306

source Fondo Giannina Censi · Mart · Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto

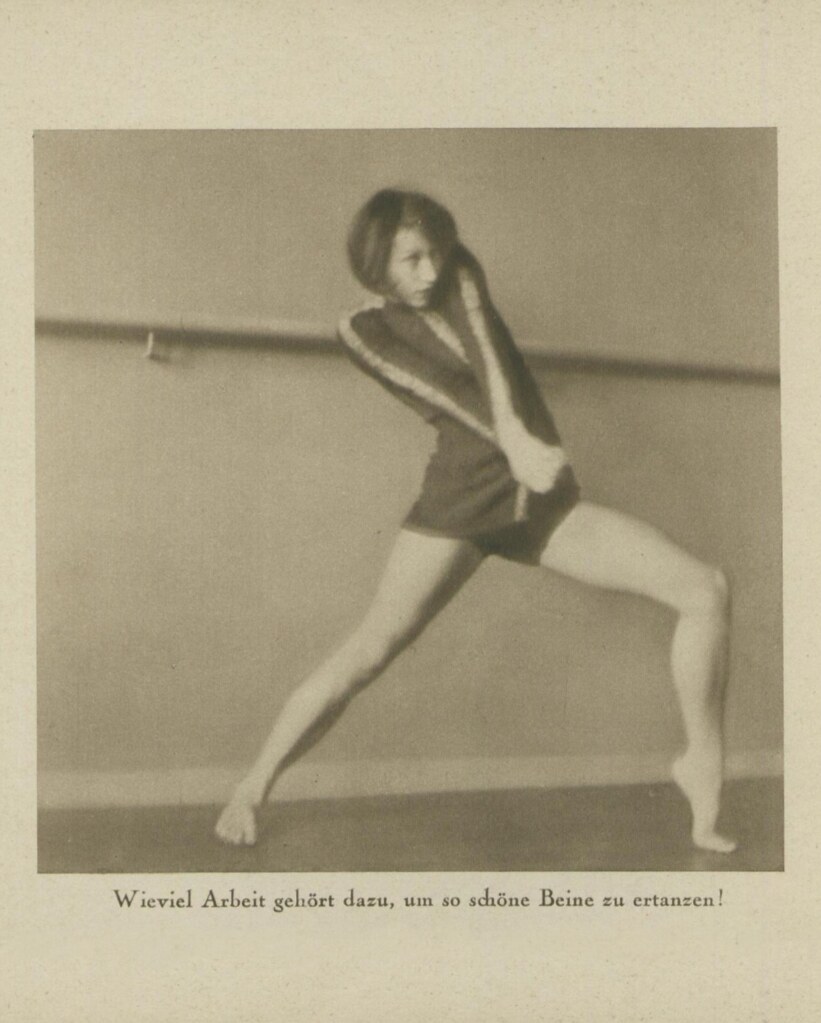

Zwanzigerjahre Die Weimarer Republik war ein Tanzparadies / In the 1920s the Weimar Republic was a dance paradise

Nothing fascinated people in the Weimar Republic as much as dance. It was a worldview and a lot of fun at the same time. This was mainly due to the fact that women set the stress here for the first time.

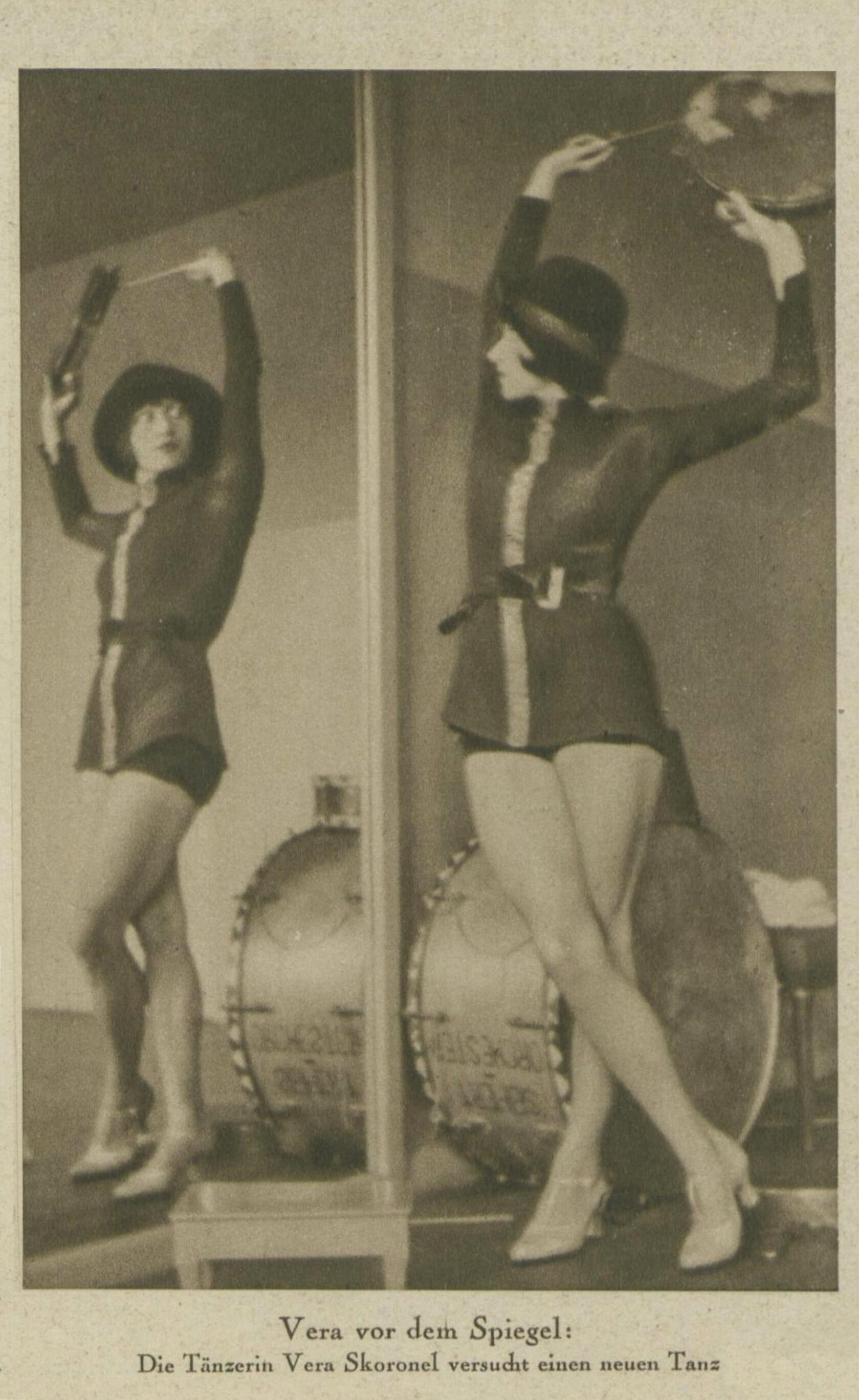

There was the nude dance, the masked dance, the grotesque dance. There was the exotic, the ecstatic, the sacred and even the socially critical dance. Yes, at its peak in 1930, the youngest hope of this trendiest art movement of the epoch, Vera Skoronel, who had just created abstract dance, asked, boisterously and of course purely rhetorically: “Non-dancing – does that even exist?”

Vera Skoronel, almost forgotten today, is a good example of how quickly creative and vivacious young women were able to establish themselves in the avant-garde art scene of the 1920s. Because Vera Skoronel, who died in 1932 at the age of only 25 after a short illness, not only became co-director of Berthe Trümpy’s famous dance school in Berlin at the age of 20.

She also received a contract at the Volksbühne a short time later. There Vera Skoronel took over the movement direction for her own pieces, but also for those of the so-called workers’ speech choruses. At that time, they represented a new literary genre and bore promising titles such as “The Divided Man” or “Awakening of the Masses”.

Awakening the masses is the keyword. Because this very specific form of dance without music, which today is usually summarized under the rubrum “expressive dance”, as Mary Wigman and Gret Palucca had invented before the First World War, not only represented a rejection of the classic narrative ballet. It is also about a very fundamental farewell to bourgeois culture.

Like the Bauhaus in architecture and design, or like the Expressionist November Group in the visual arts, dance must be seen as a specific phenomenon of the Weimar Republic. Only conceivable in the turbulent and experimental interwar period. But the dance also carried a fair amount of youthful and typically German worldview with it. Because he really wanted to liberate, awaken, if not redeem.

Tanz als Religionsersatz / Dance as a substitute for religion

Awaken for what? Well, of course, first and foremost to the awareness of one’s own body in its naturalness and in allowing needs to be met. The barefoot dancer Isadora Duncan had already broken with the corseting of the dress code before the First World War. What was added after 1918 was the need to merge with other arts and to convert the old German treatment of art as a substitute for religion into new forms.

Another German cultural phenomenon quickly developed again: the splitting up into high culture and subculture. On the one hand, Anita Berber, who was incredibly popular at the time (she even became a Rosenthal porcelain figurine!) gave solos called “Morphium” or “Cocain”. And she tried to authenticate herself by taking these substances so intensively that she collapsed on the open stage in her late 20s and died shortly thereafter.

On the other hand, Charlotte Bara made herself the brand of a “Gothic dancer”. With deliberately slow movements, she aimed at the sacred, the priestly. Unlike Berber, she did not try to come to terms with the catastrophe of the world war in excess, but to come to terms with the tremendous suffering that the fateful four years had brought to Europe through a new spirituality.

Schmerzensgestik / Pain gesture

And that did not only appeal to Heinrich Vogeler in Worpswede, who left Art Nouveau behind and struggled with new forms after 1918. We owe him a particularly expressive portrait of the Bara, which presents her as almost ecstatically fervent. But even a moderate nature like Georg Kolbe was attracted to Charlotte Bara’s gestures of pain.

With Georg Kolbe we have arrived at the place where the most famous dancers of the Weimar Republic have once again gathered: in Kolbe’s studio museum in Berlin’s Westend. There are eleven of them – perhaps a small nod to the first avant-garde group in Berlin: the exhibition group “The Eleven”, which rallied around Max Liebermann in 1892.

Der absolute Tanz / The ultimate dance

Each of these dancers is different, each unmistakable, each swept up in the whirlpool of that time and often swallowed up by it early on. But they all have one thing in common: they take the viewer on a journey into a time that experienced a rare explosion of creativity. With a staggering abundance of testimonies, the exhibition“Der absolute Tanz” proves that no other art genre can be understood as a metaphor for the restless movement of the 1920s as clearly as dance.

With the help of films, photos, drawings, paintings and sculptures, the Georg Kolbe Museum evokes an attitude to life that seems to stretch in a very unique way between new beginnings here, self-wasting, self-consumption there.

The grotesque dancer Valeska Gert, one of the very few who were granted a comeback after the collapse of civilization, represents the radical side of this attitude towards life. At the peak of her career she said: “The old world is rotten, it cracks at every joint. I want to help break them. I believe in the new life. I want to help build it.”

Solidarität mit Bedürftigen / Solidarity with the needy

Jo Mihaly and Tatjana Barbakoff did the same, to introduce at least two more dancers. The former, whose real name is Elfriede Alice Kuhr, had chosen the name of a Roma-family as a pseudonym, which gave her the name Jo Mihaly out of gratitude, which means something like “one of them”. Mihaly was serious about her solidarity with the needy. For a long time she lived without a permanent address and was successful with solos called “Revolution” or “The Worker”, in which she also portrayed men. Like many of her colleagues, she continued her work in Switzerland after 1933: on Monte Verità.

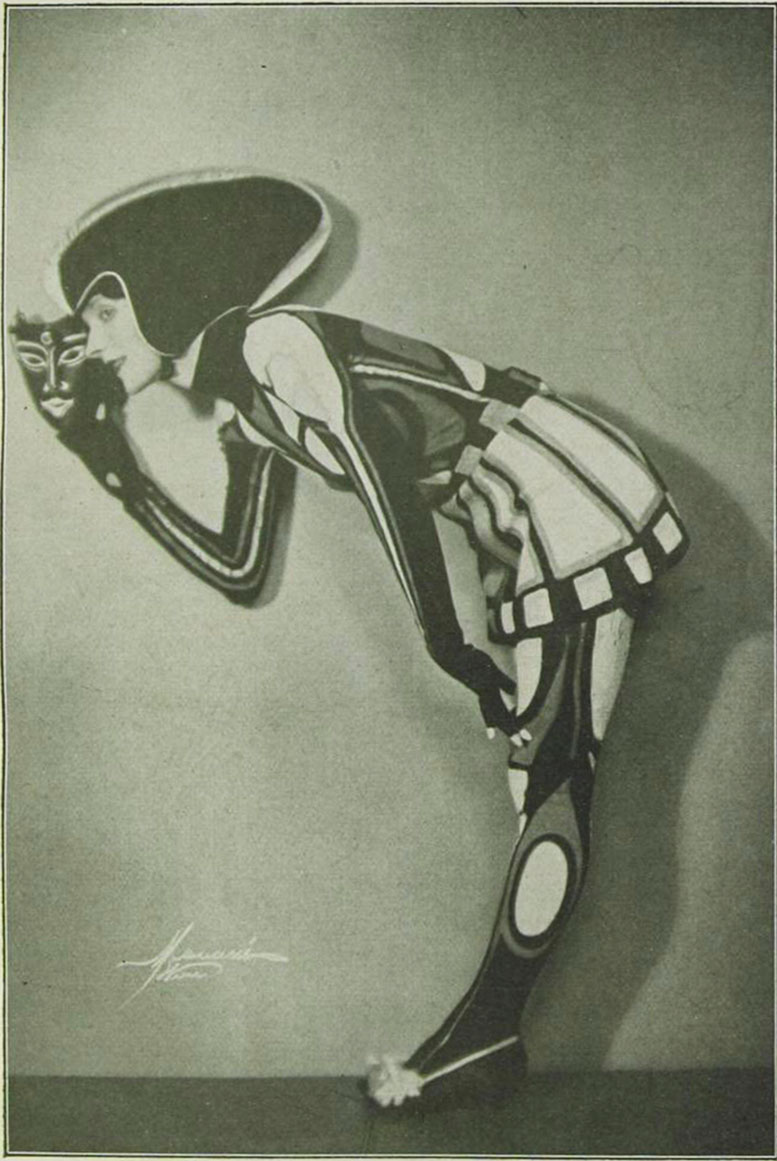

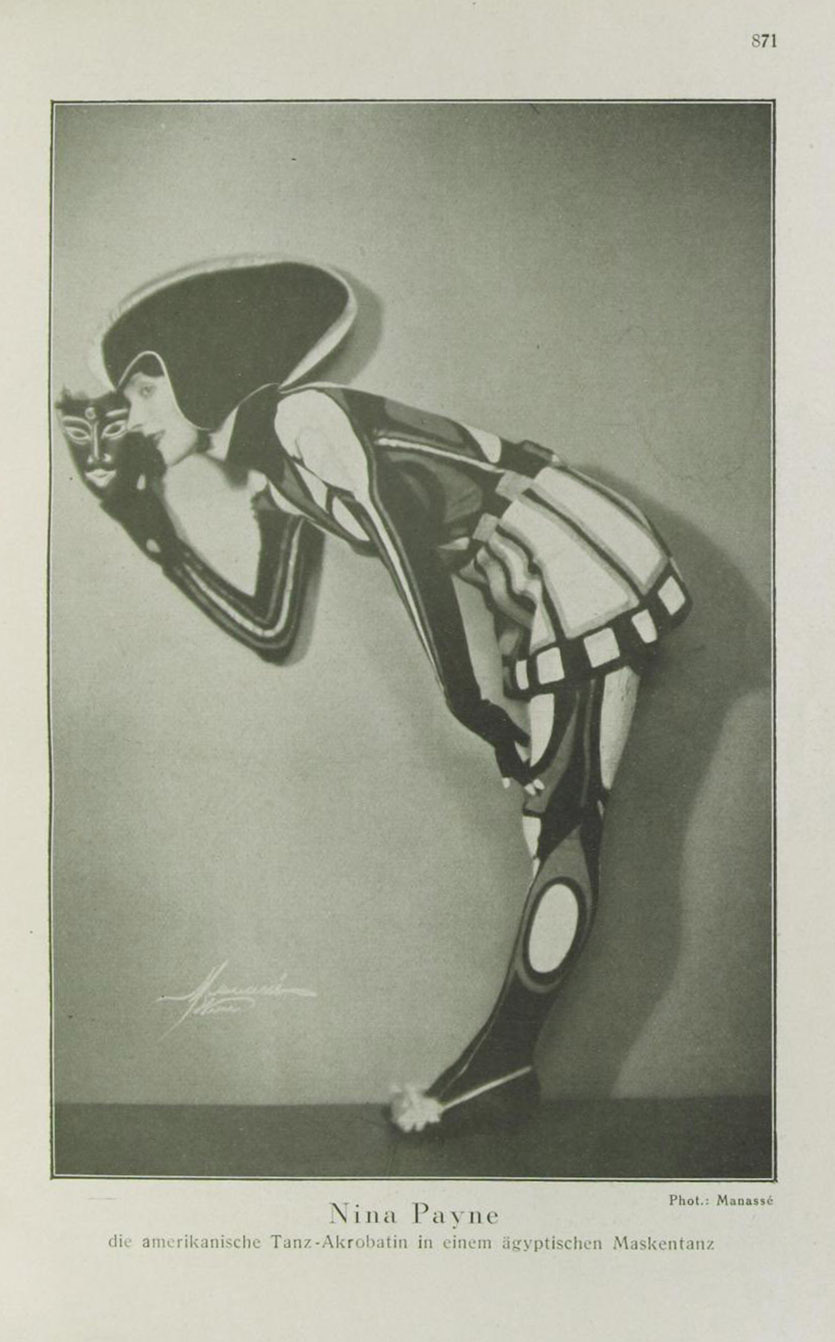

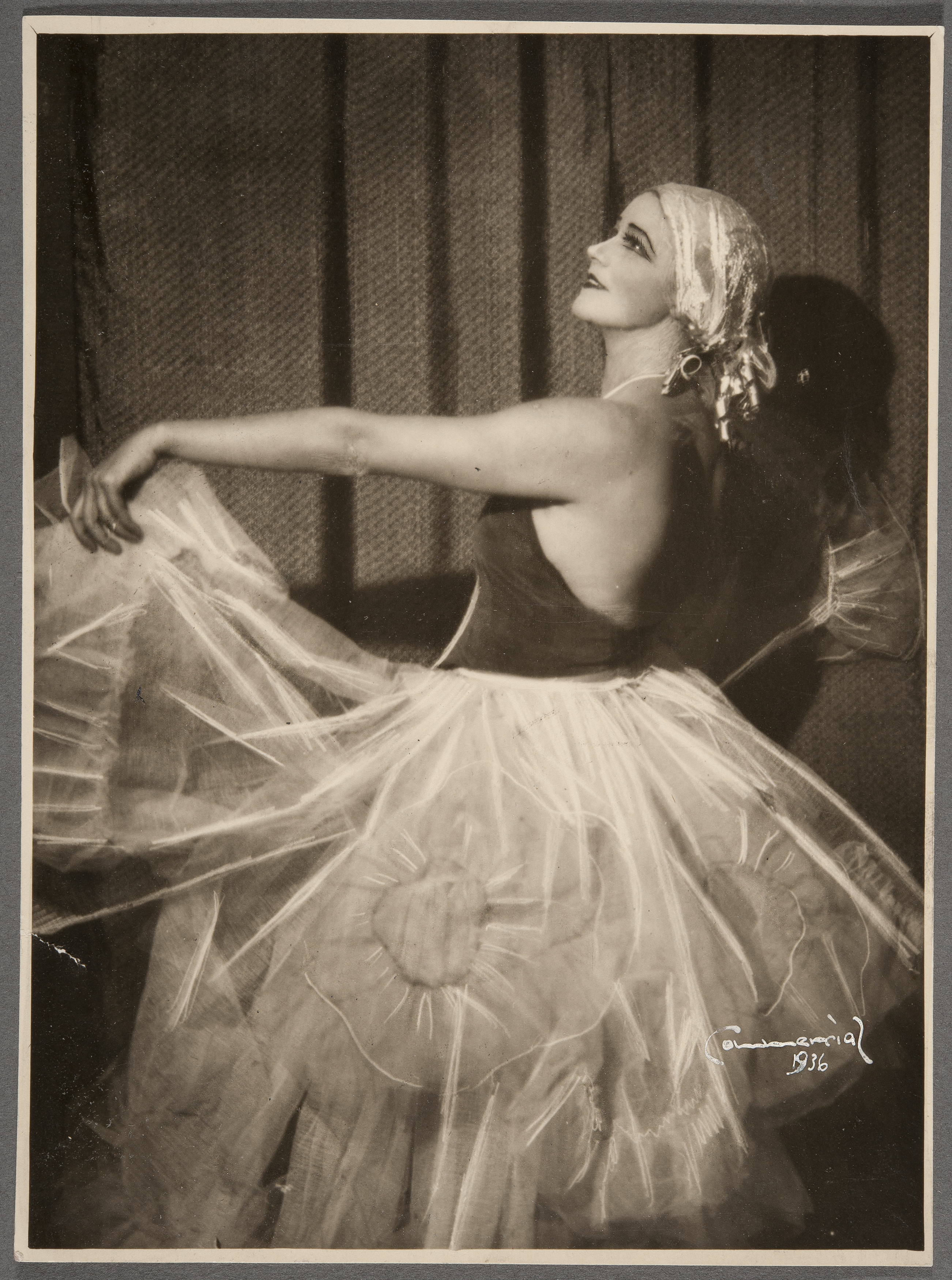

Tatjana Barbakoff focused on exploring non-European cultures and experimenting with their dance traditions. She was a grateful object of the dance photography of the time, also a new artistic genre that is richly documented in the Georg Kolbe Museum. Anyone who looks at the recordings and sees Barbakoff performing her exotic movements in fantastic costumes cannot help but get the impression that our contemporaries are at work here.

Here, a feminine aesthetic speaks up, self-confident, curious, ready to test itself, which has only fully developed in recent years. We should take note of this dawn of modernity – and allow ourselves to be carried away by its verve.

„Der absolute Tanz. Tänzerinnen der Weimarer Republik“, Georg Kolbe Museum, Berlin.

“The ultimate dance. Dancers of the Weimar Republic”, Georg Kolbe Museum, Berlin.

quoted from Welt, roughly translated by us with the aid of Google-traductor, any amend and/or help will be most welcome.

Organized by Georg Kolbe museum, in the framework of “Die absoluten Tänzerinnen”, available on Spotify (Episode 7)

“Vera Skoronel, a true exceptional talent of modern expressive dance. She was confident, charismatic, her enthusiasm infectious. “Not-to-dance – does that even exist?” she once asked, purely rhetorically, of course.” quoted from source