Liberian Coffee, 1870s

images that haunt us

(*) Note: not orchids but irises; vase with irises. Unless they were a variety of orchids that look very much like irises. If anybody happen to have the knowledge to disambiguate, please drop a line below. Thank you!

“Le sujet le plus banal, quelques fleurs dans un vase par exemple, devient nouveau par la façon dont les lumières y sont groupées et par l’extrème variété des valeurs. (…) Pour donner plus de richesse à ses compositions, l’auteur [Laure Albin Guillot] les a tirées sur fond or selon un procédé dont elle a le brevet.”

Jean Gallotti, ‘La photographie est-elle un art? Laure Albin-Guyot [sic!]’, dans L’art vivant, No. 99, 1er février 1929, p. 138. [Quoted from Sotheby’s]

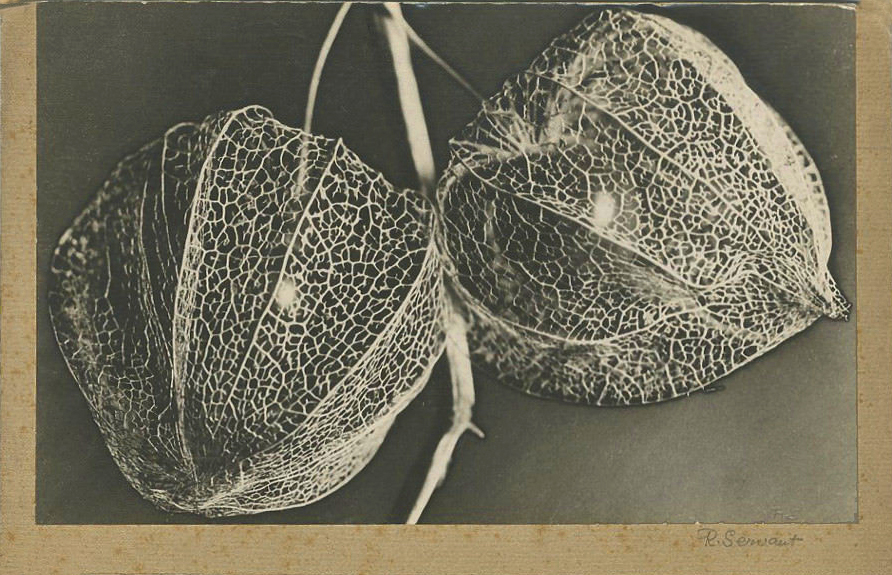

This experimental proof is a fine example of the capacity of Talbot’s “photoglyphic engraving” to produce photographic results that could be printed on a press, using printer’s ink-a more permanent process than photographs made with light and chemicals. Like Talbot’s earliest photographic examples, the image here was photographically transferred to the copper engraving plate by laying the seeds directly on the photosensitized plate and exposing it to light, without the aid of a camera. Equally reminiscent of Talbot’s early experiments, this image is part of Talbot’s lifelong effort to apply his various photographic inventions to the field of botany. In a letter tipped into the Bertoloni Album, Talbot wrote, “Je crois que ce nouvel art de mon invention sera d’un grand secours aux Botanistes” (“I think that my newly invented art will be a great help to botanists”). Such uses were still prominent in Talbot’s thinking years later when developing his photogravure process; he noted in 1863 that “if this art [of photoglyphic engraving] had been invented a hundred years ago, it would have been very useful during the infancy of botany.” Had early botanists been able to print fifty copies of each engraving, he continued, and had they sent them to distant colleagues, “it would have greatly aided modern botanists in determining the plants intended by those authors, whose descriptions are frequently so incorrect that they are like so many enigmas, and have proved a hindrance and not an advantage to science.” [quoted from The Met]