Whitney Lewis-Smith :: Death of The Moth, 2014. From ‘A Garden Of Natural Fascinations’ series.

Large format glass plate photography / via

les-sources-du-nil / original src: Whitney Lewis-Smith

more [+] by this photographer

images that haunt us

Whitney Lewis-Smith :: Death of The Moth, 2014. From ‘A Garden Of Natural Fascinations’ series.

Large format glass plate photography / via

les-sources-du-nil / original src: Whitney Lewis-Smith

more [+] by this photographer

Max Baur :: Tulips, another sublime photography of flowers from the 1930′s. / src: The English Group

more [+] by this photographer

Jean-Eugene-Auguste Atget :: Flowers (Hollyhocks), ca. 1900 Medium: Albumen print / via zzzze

more [+] by this photographer

Phipps Conservatory was presented as a gift to the City of Pittsburgh from philanthropist Henry W. Phipps, who wished to “erect something that [would] prove a source of instruction as well as pleasure to the people.” In a letter to City of Pittsburgh Mayor H.I. Gourley in November 1891, Phipps expressed his intentions to add this new conservatory as a complement to an already existing “Phipps Conservatory” built in 1887 in Allegheny, now known as the North Side. Henry Phipps stipulated that both conservatories operate on Sundays in order to allow the working people to visit on their day of rest.

On Dec. 7, 1893, Phipps Conservatory opened to the public. It showcased over 6,000 exotic plants originating from the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago — cacti, trees, ferns and more made the journey by train and horse-drawn cart to Pittsburgh and the nation’s newest and largest conservatory.

In 1895 Phipps Conservatory hosted the 26th Triennial Conclave of the Knights Templar, during which this iconic image was captured. In the photo, a woman, Angie Means, stands on a giant Amazonian water lily pad, or Victoria regia, in the Victoria Room.

In October 1898, the 27th Triennial Conclave of the Knights Templar was held in Pittsburgh. Horticulture staff decorated the Conservatory with flowerbeds designed as Masonic emblems for the Conclave’s visit on Oct. 13th.

src Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens and USC

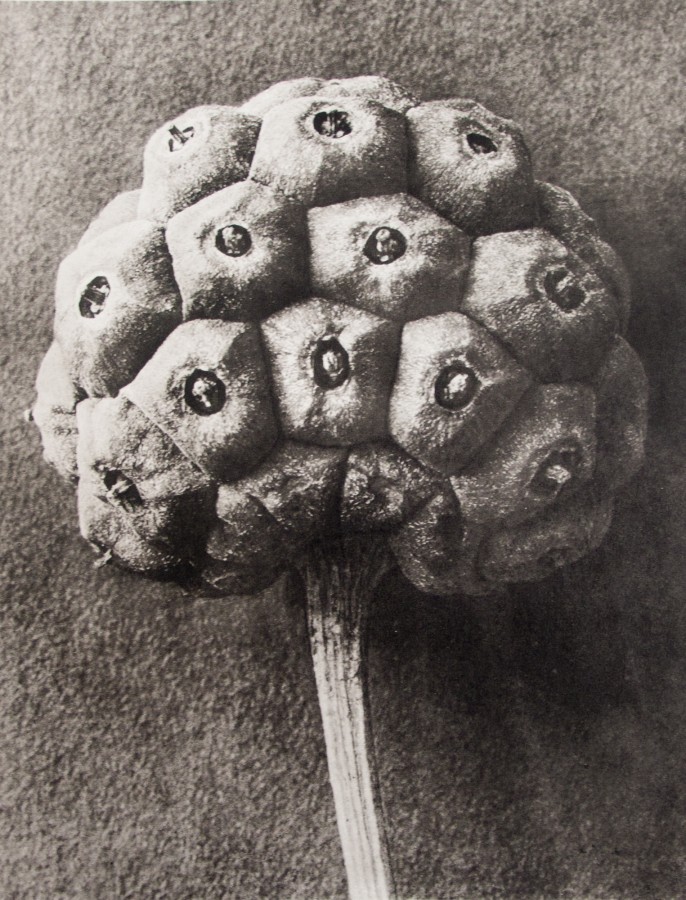

Karl Blossfeldt ::

Cornus-Kousa (Dogwood), 1920′s / Stiftung Ann und Jürgen Wilde, Pinakothek der Moderne, München./ src: Michael Hoppen Gallery

more [+] by this photographer

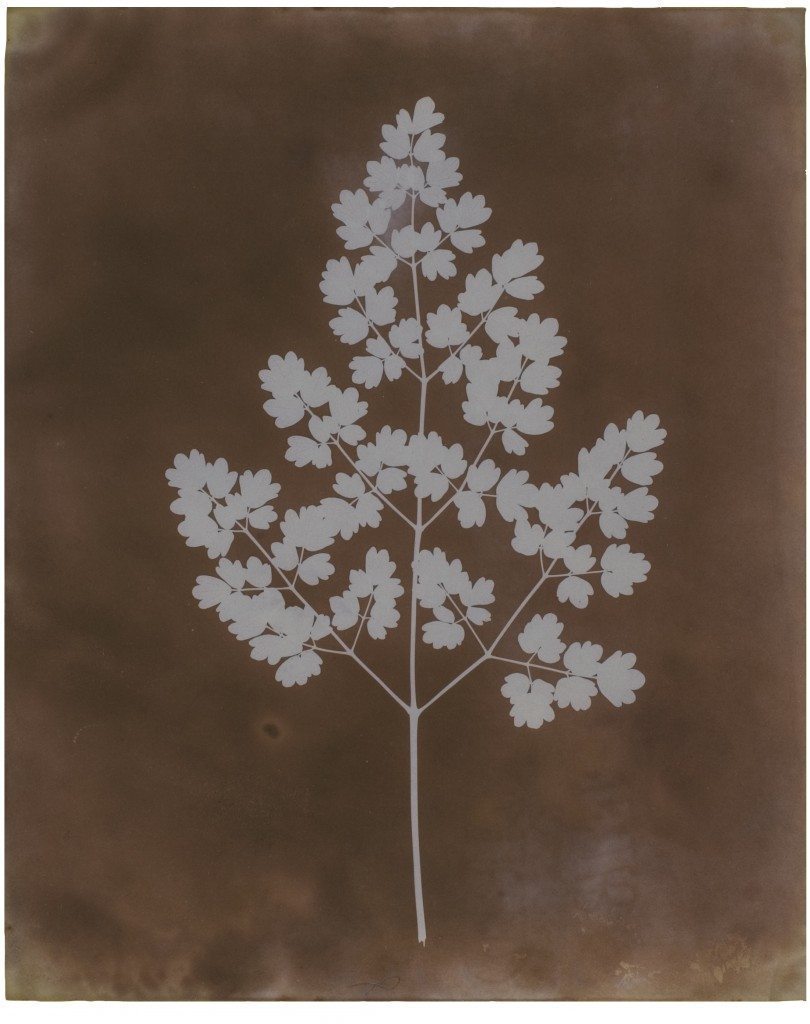

This image of a fern was an experiment by Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot. It probably dates back to 1839, the year in which he publically announced his invention of paper photography. But back then, this did not mean taking a snap using a camera in the sense that we understand it today. This was a photogram. Talbot took a small object with delicate contours like a piece of lace or a plant specimen and exposed it to light on a sheet of paper that had been bathed in a solution of salt and silver nitrate. When the object was removed after having been exposed to sunlight (a trial and error process to determine how long it should be exposed to best effect), a clear silhouette would emerge from the darkened background of the paper.

Talbot is the English inventor of photography, just as Niépce and Daguerre were the French inventors of the same. While Daguerre was working alongside Niépce and fine-tuning the daguerreotype process, Talbot, who didn’t have a clue about their research, was experimenting with photography on paper himself in his property at Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire. His early interest in botany, maths, travel and a meeting with the great scientist John Herschel in 1824 fuelled his passion for the physical and chemical sciences. His light bulb moment came in 1833 when on honeymoon at Lake Como. His idea was to chemically fix the images produced by the camera obscura used by artists at the time to create sketches from nature. He succeeded around mid 1830. It was the first time that an image had been created without human intervention, hence the word photogenic drawings followed by the expression photography, a word created from two Greek words meaning «written with light».

The story goes that these delicate little silhouettes that look like herbarium plants or sketches by naturalists became the first manifestations of the invention – and great revolution – of photography. [quoted from src]