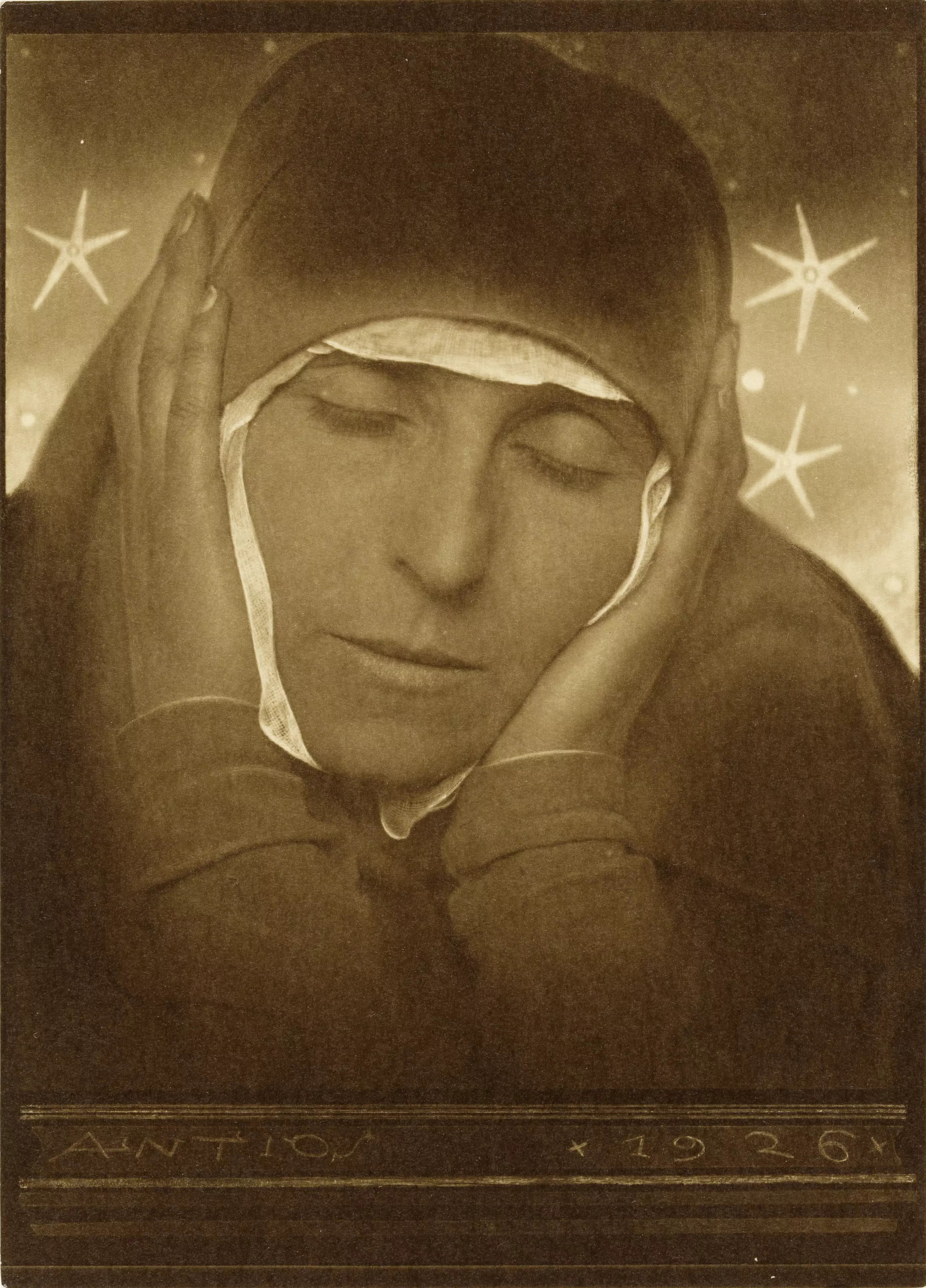

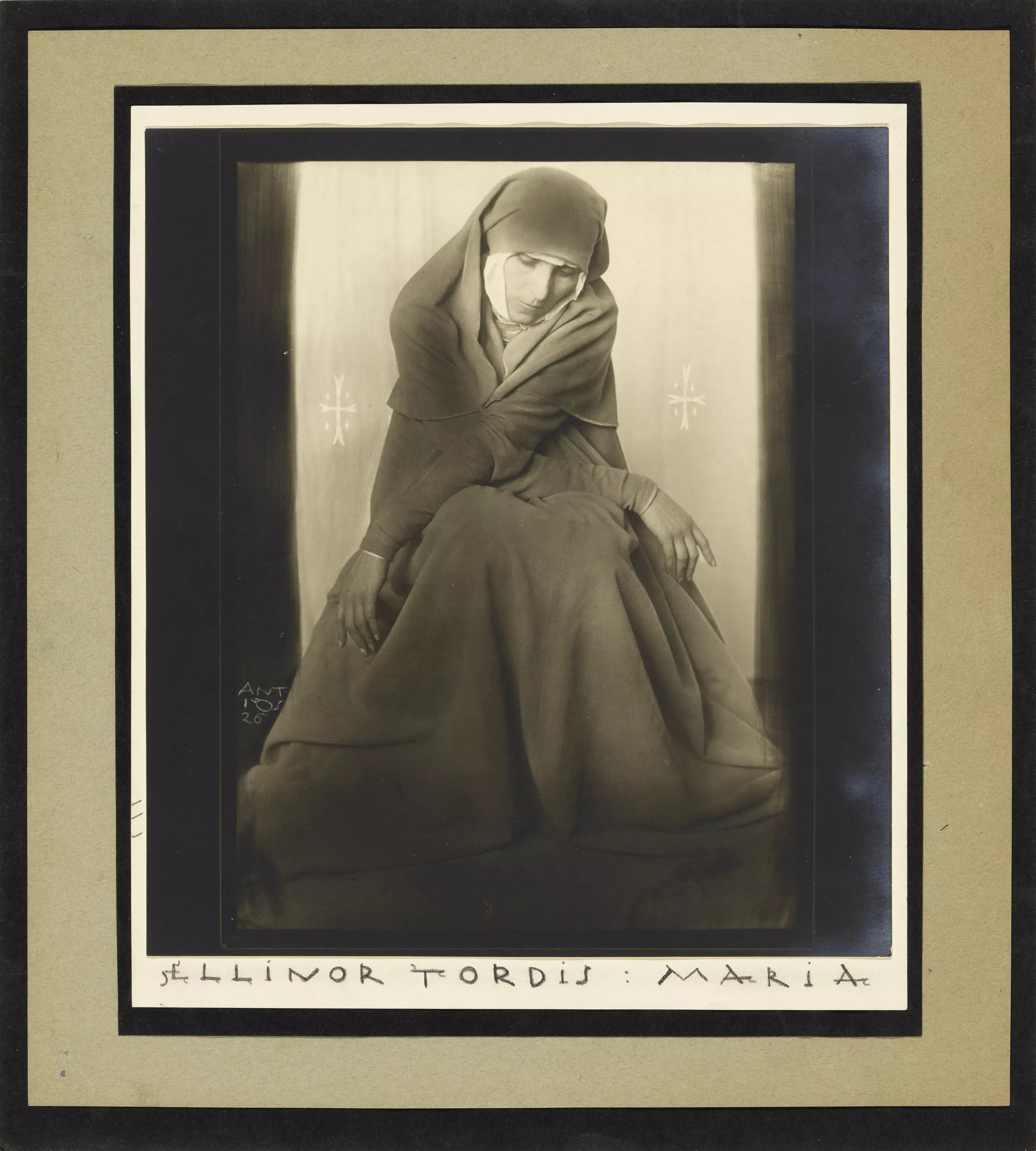

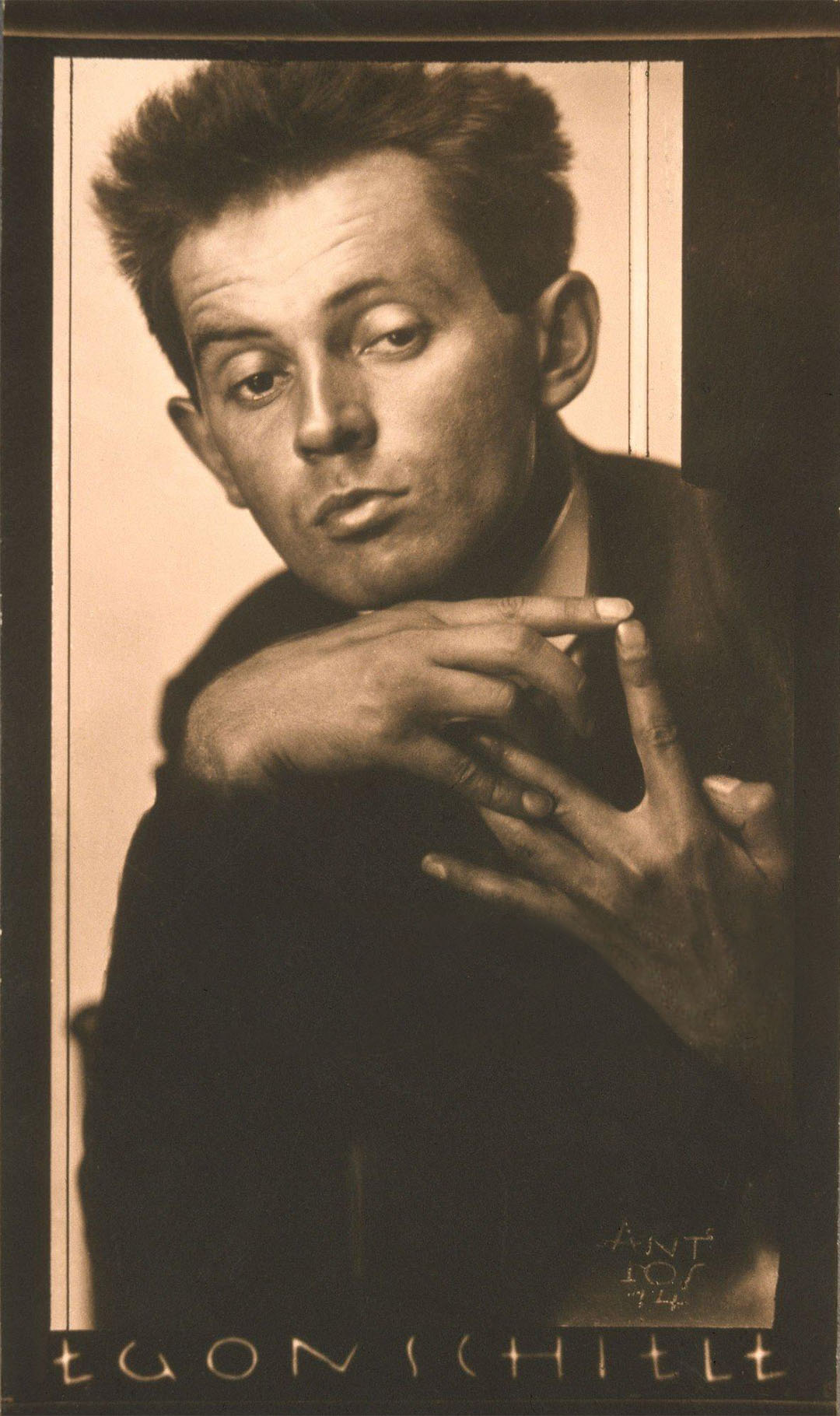

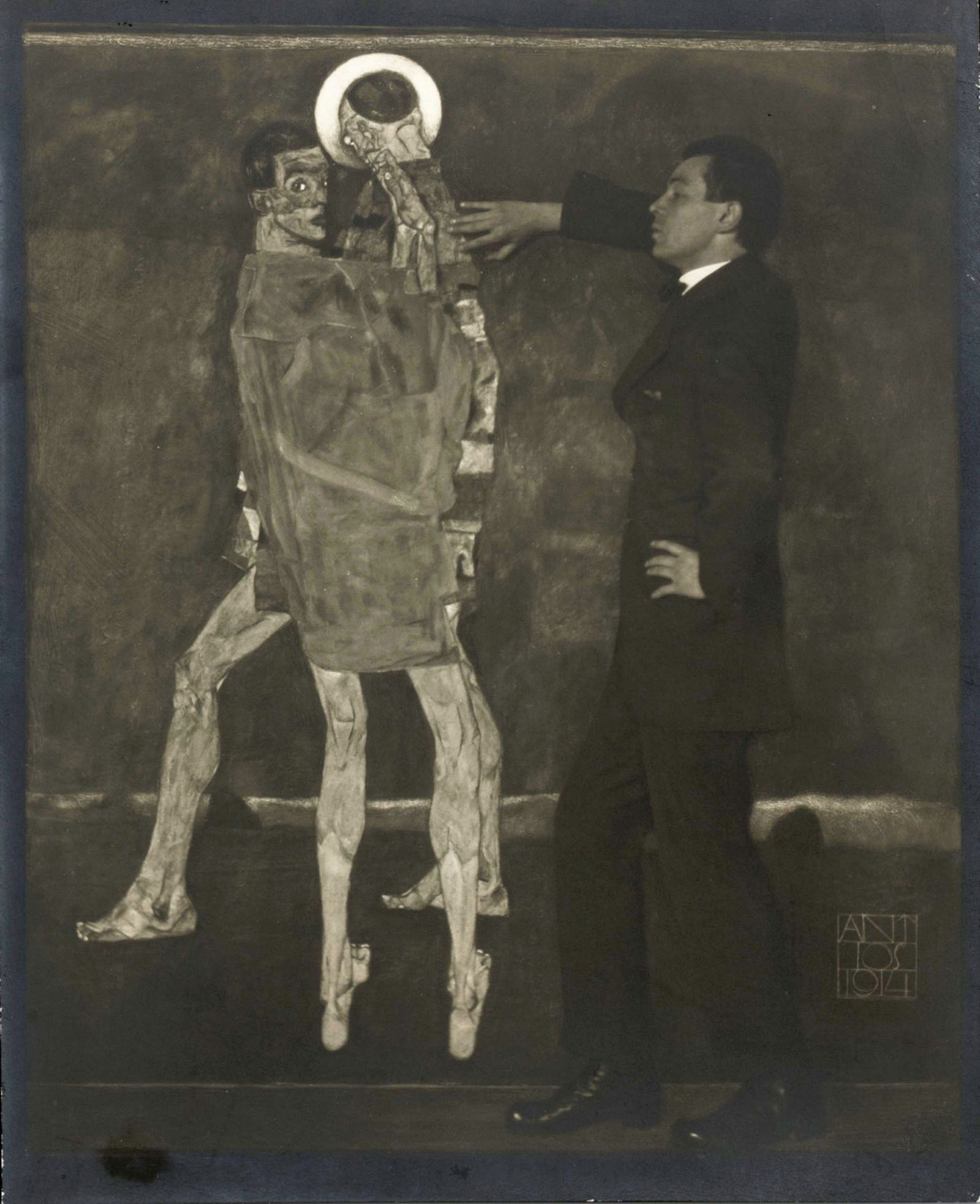

ANTIOS – this clearly legible and decorative signet is as much an effective design element of these famous portraits as EGON SCHIELE’s signature. For a long time, it seemed no one was interested in the fact that this legendary Viennese painter and self-portraitist could not have produced such accomplished photographs without the cooperation of a partner who was a master of photographic technique. The way expressive movement blends with the demands of ”classic” portraiture, or the way graphic outline contrasts with the two-dimensional rendering of figures and garments – this cannot have been the work of an amateur.

An amateur he certainly was not, this Anton Josef Trčka, who contracted his own name to form the artistic trademark ANT(on) IOS(ef) during his third year of studies at the “Graphischen Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt” (Institute of Graphic Instruction and Experimentation) in Vienna. This specialized learning institute for photography and reproduction technology, the first of its kind worldwide, was founded in 1888 in the tradition of the commercial arts schools, and combined the demand for technical perfection with solid instruction of an artistic nature. The young Trčka found in Karel Novak (later the co-founder of a similar school in Prague that produced the likes of Sudek or Rössler) a teacher, who not only taught his students how to turn the idea of Pictorialism into professional practice, but also conveyed an understanding of classical portraiture and a love of contemporary painting. The level of Novak’s influence can be seen in the way artists such as Rudolf Koppitz or Trude Fleischmann, along with ANTIOS, remained true their life long to decorative design devices particular to their teacher.

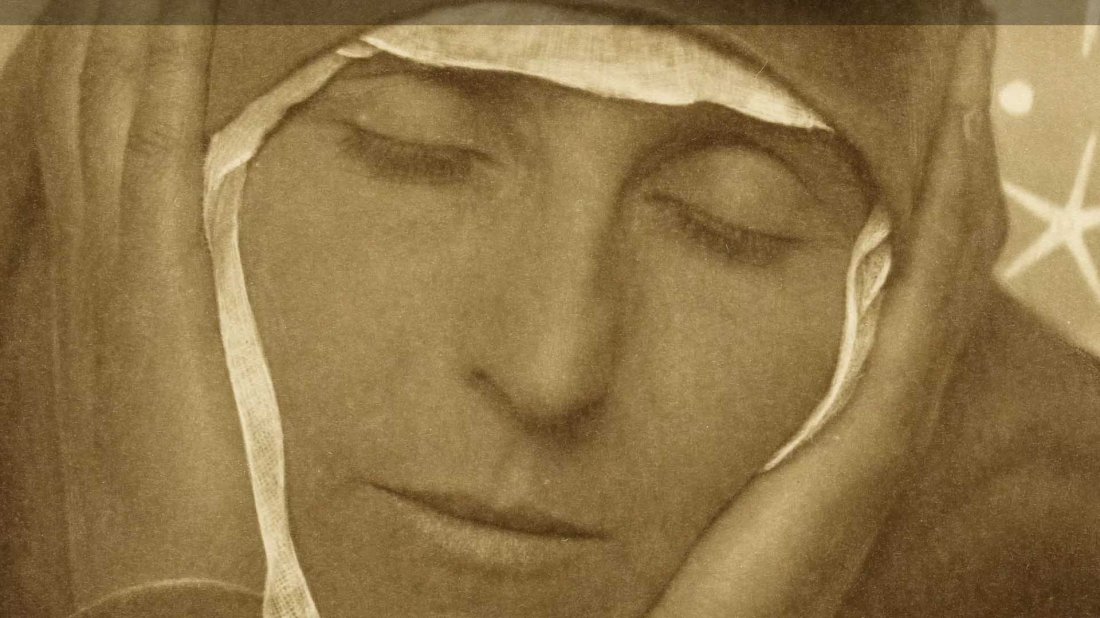

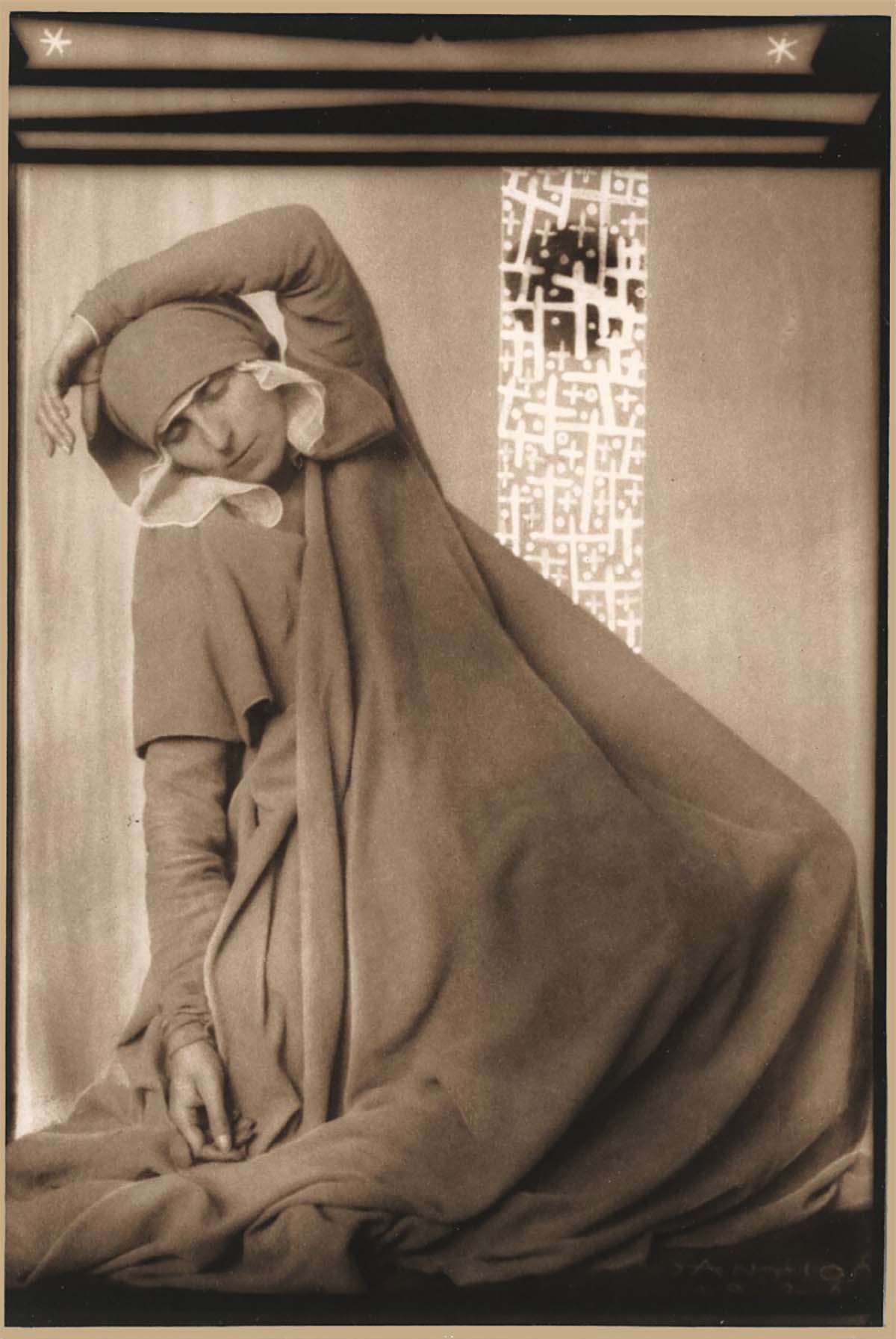

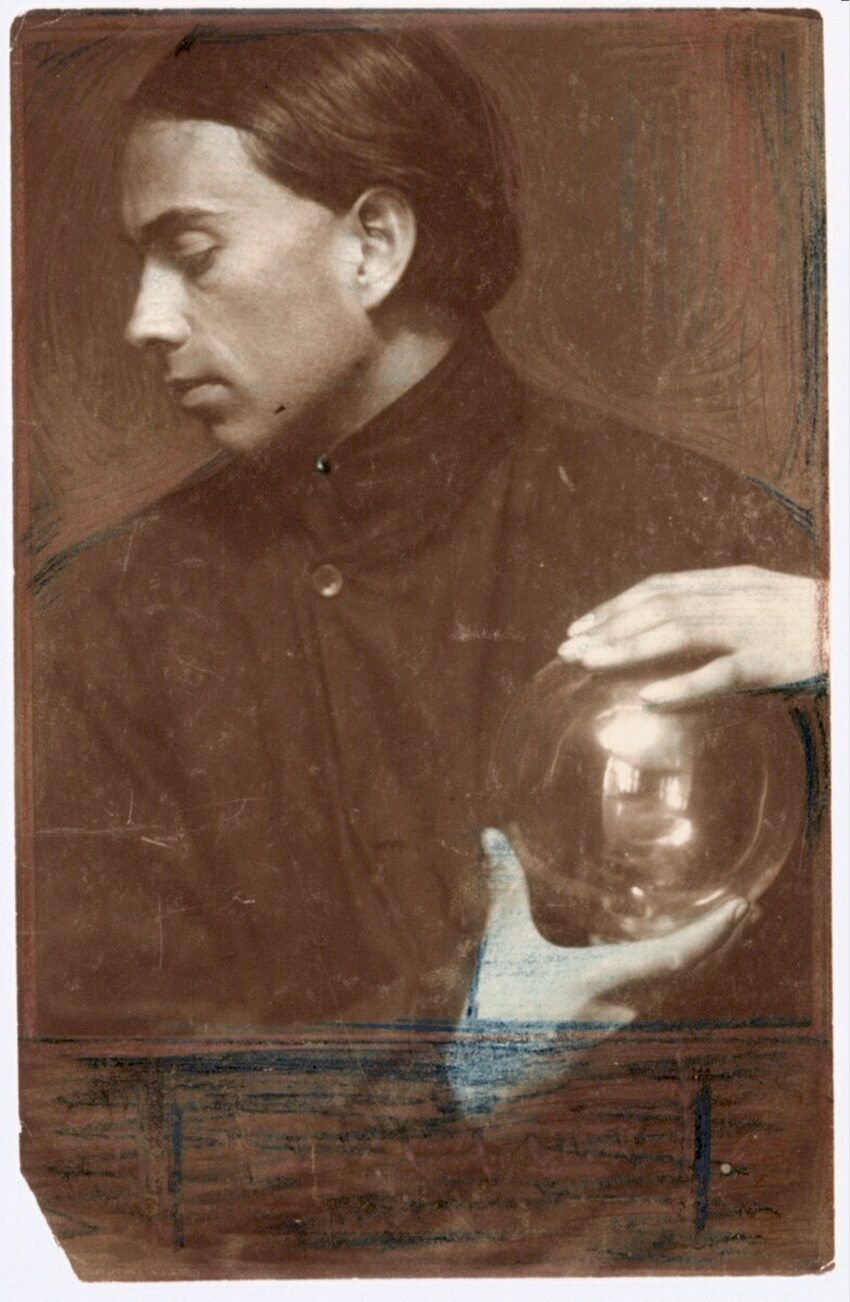

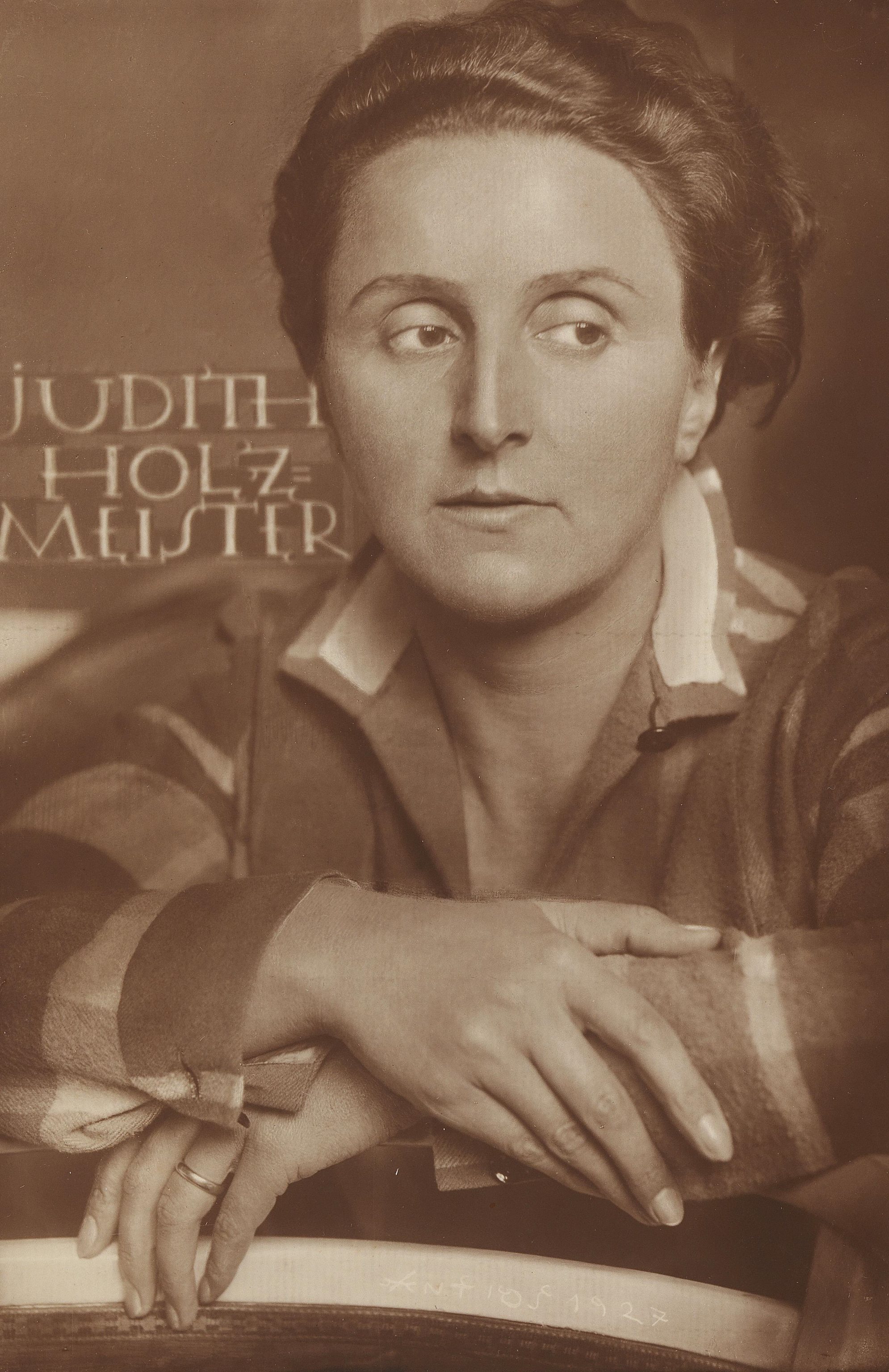

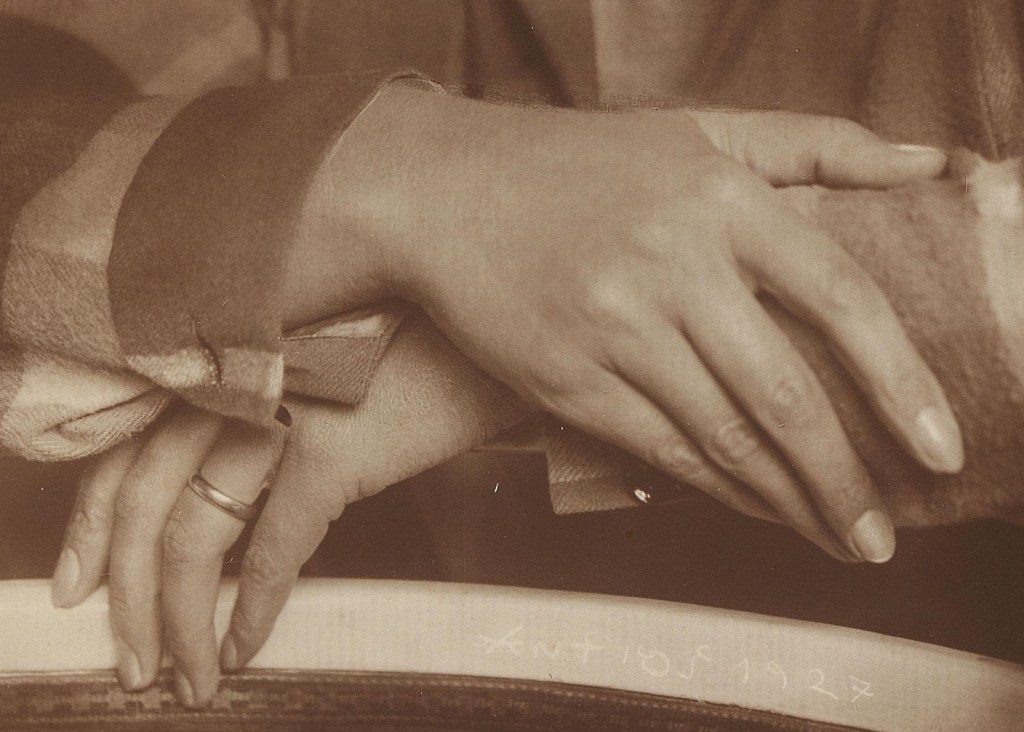

Well before his Schiele and Klimt portraits, ANTIOS had experimented with compositions that were indebted to Jugendstil. The dynamic contours of his figures appear to be inspired by the work of those young dancers who, in the first decades of the 20th century, consciously distanced themselves from classical ballet. By 1924, Trčka had developed close friendships with several dancers, including Hilde Holger and Gertrud Bodenwieser, and these found expression in photographic dance studies, nudes and portraits, and even drawings and poems. During this period, he developed a portrait style that clearly sets him apart from what is generally considered to be the international avant-garde of the 1920’s, yet at the same time is far removed from the great amateur art photographers at the turn of the century. ANTIOS’s imagery – with its wonderfully circular compositions, the painterly reworking by the artist himself, and the integration of the image title and his signature – radiates a deeper melancholy stemming from a determination for perfection that stands diametrically opposed to the photographic goals of the ”Neues Sehen” movement.

As early as his student years, the young Trčka considered himself not only a photographer but also – or mainly! –a painter and poet. And he put these inclinations to use in the service of his intense interest in religion, theosophy and anthroposophy. His admiration for Rudolf Steiner was second only to his admiration for Otokar Brezina, a Czech Poet who at the turn of the last century, created a language based on religion and nature that turned against traditional poetry as well as the hated Austrian domination. Due to this conflict between his Czech roots and the Austrian identity forced (due to economic reasons) on him, and driven with missionary zeal for Anthroposophy, Anton Josef Trcka would be damned to a lifelong existence on the margins. He saw his photographs and paintings exhibited only once in his lifetime, his poetry was made public only through private readings. However, his few friends and admirers, such as Hilde Holger, found in his work something extraordinary that accompanied them in times of escape or emigration. (Text by Monika Faber) ~ quoted from Galerie Kicken Berlin