images that haunt us

Kadel & Hebert :: «Centipede crown». Coiffe portée par l’actrice Paulette Duval. Etats-Unis, 1926 Tirage argentique. | Galerie Lumière des Roses

Centipede crown (1926) — un regard oblique

Ferdinand Flodin (1863-1935) :: Titel saknas, u.å. | Untitled, nd | src Moderna Museet ~ Helmer Bäckströms fotografisamling

Rokoko by Ferdinand Flodin — un regard oblique

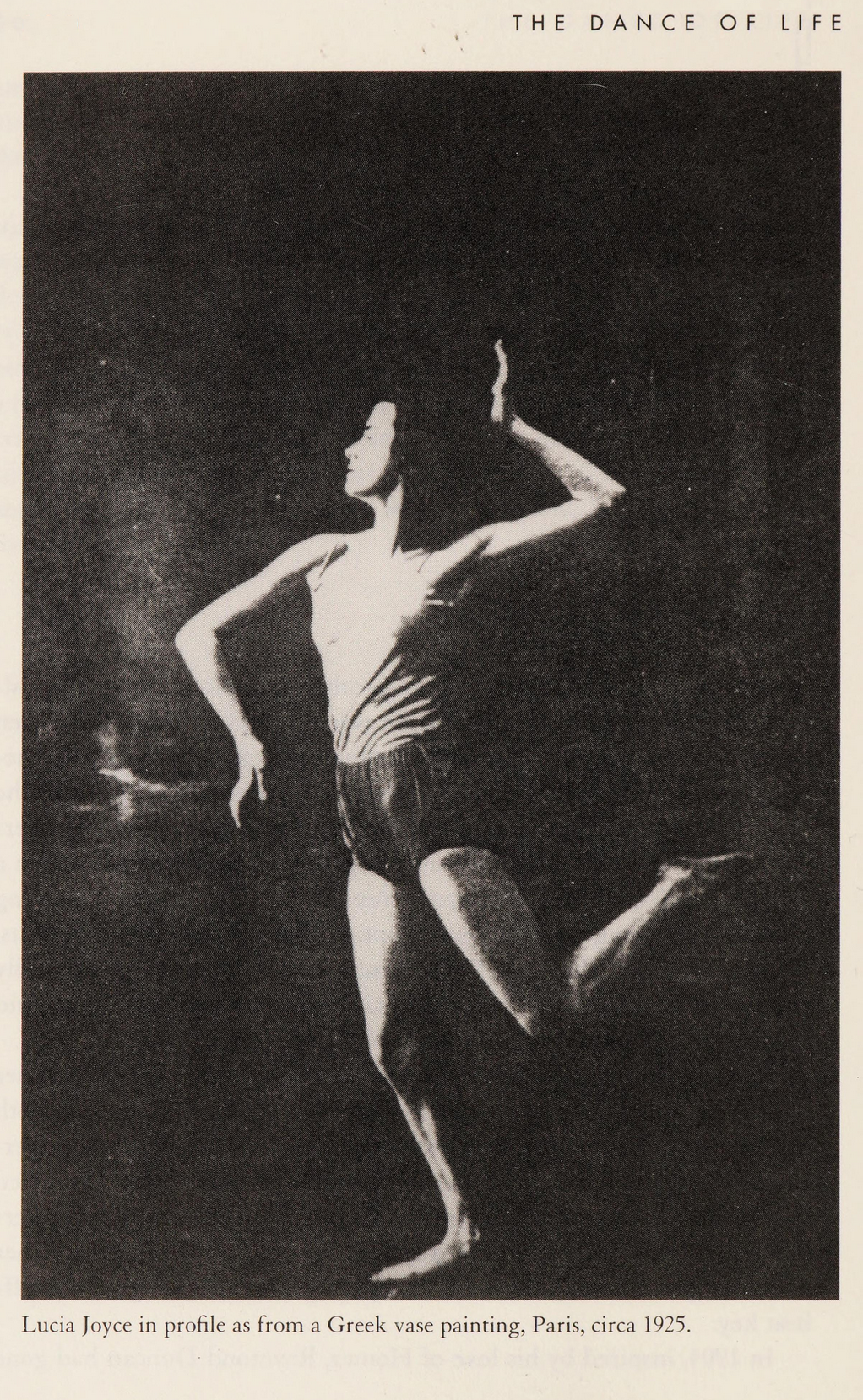

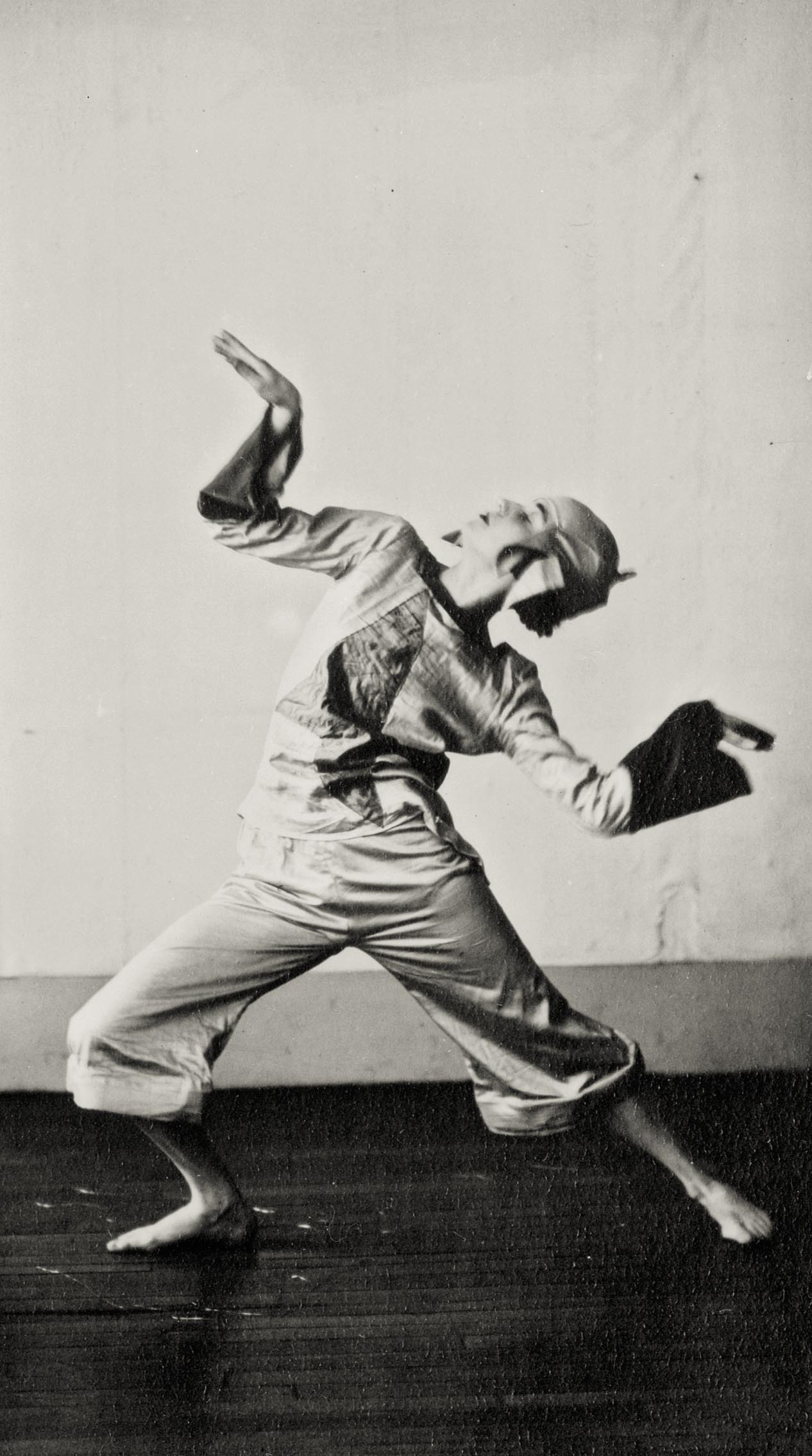

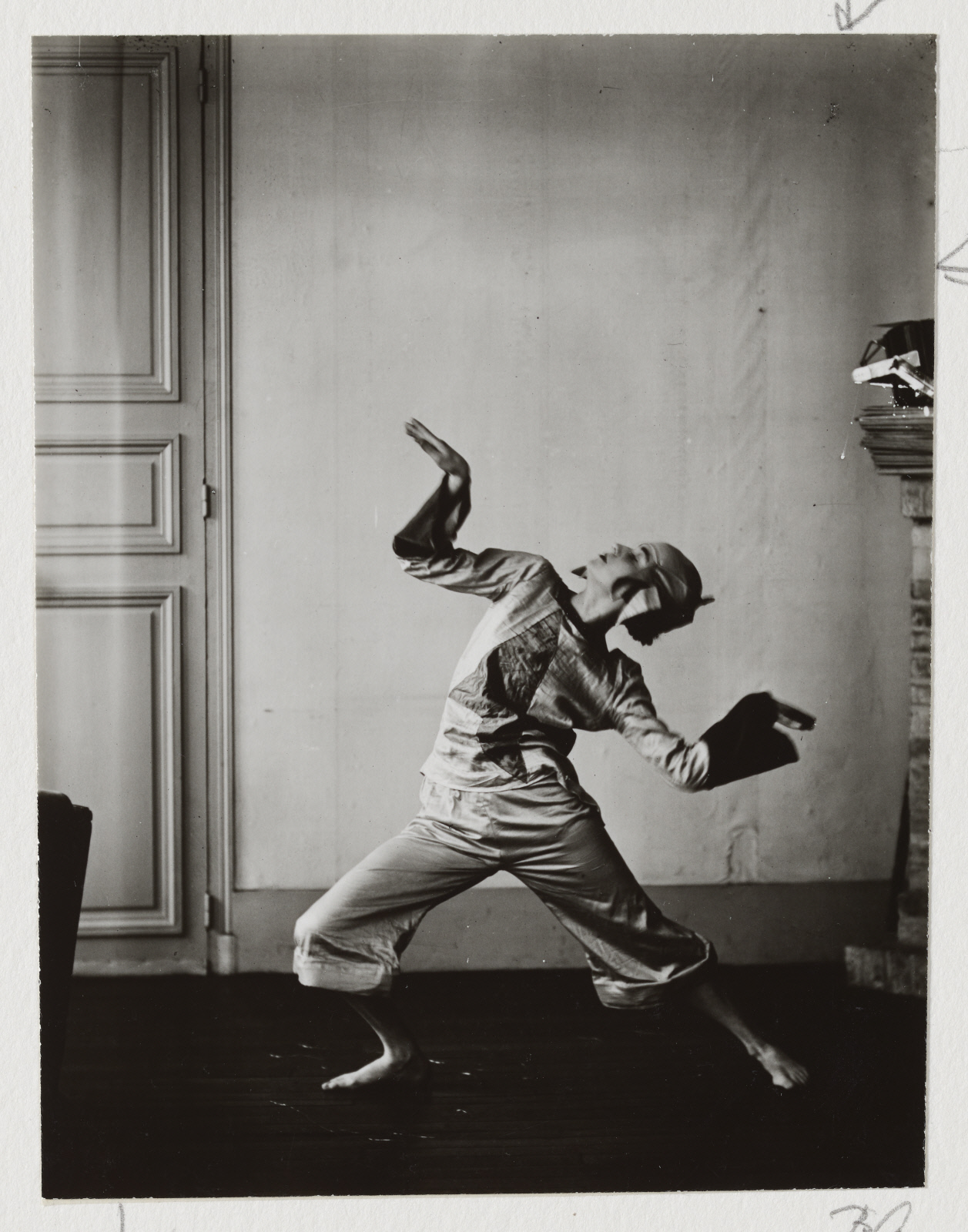

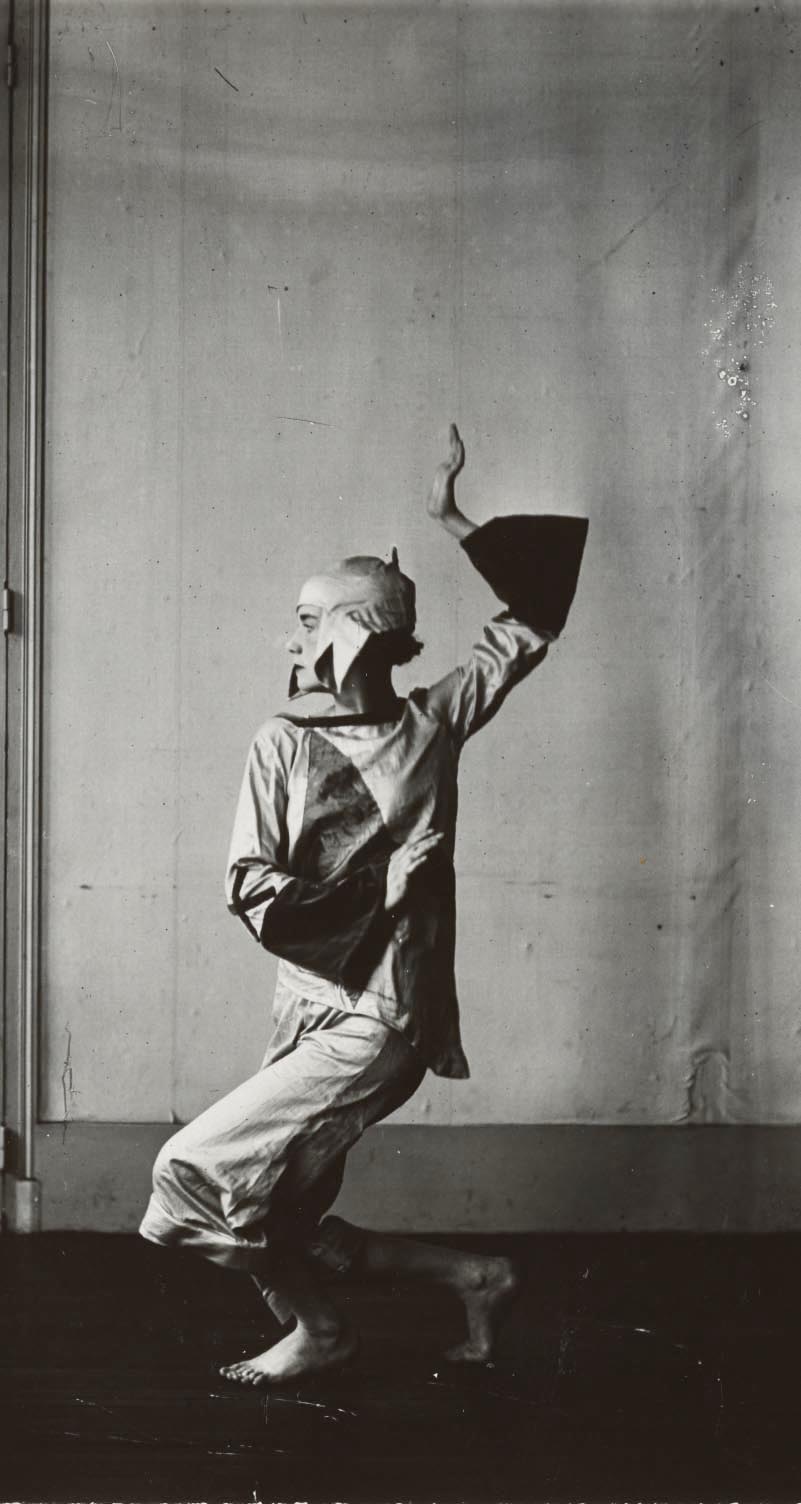

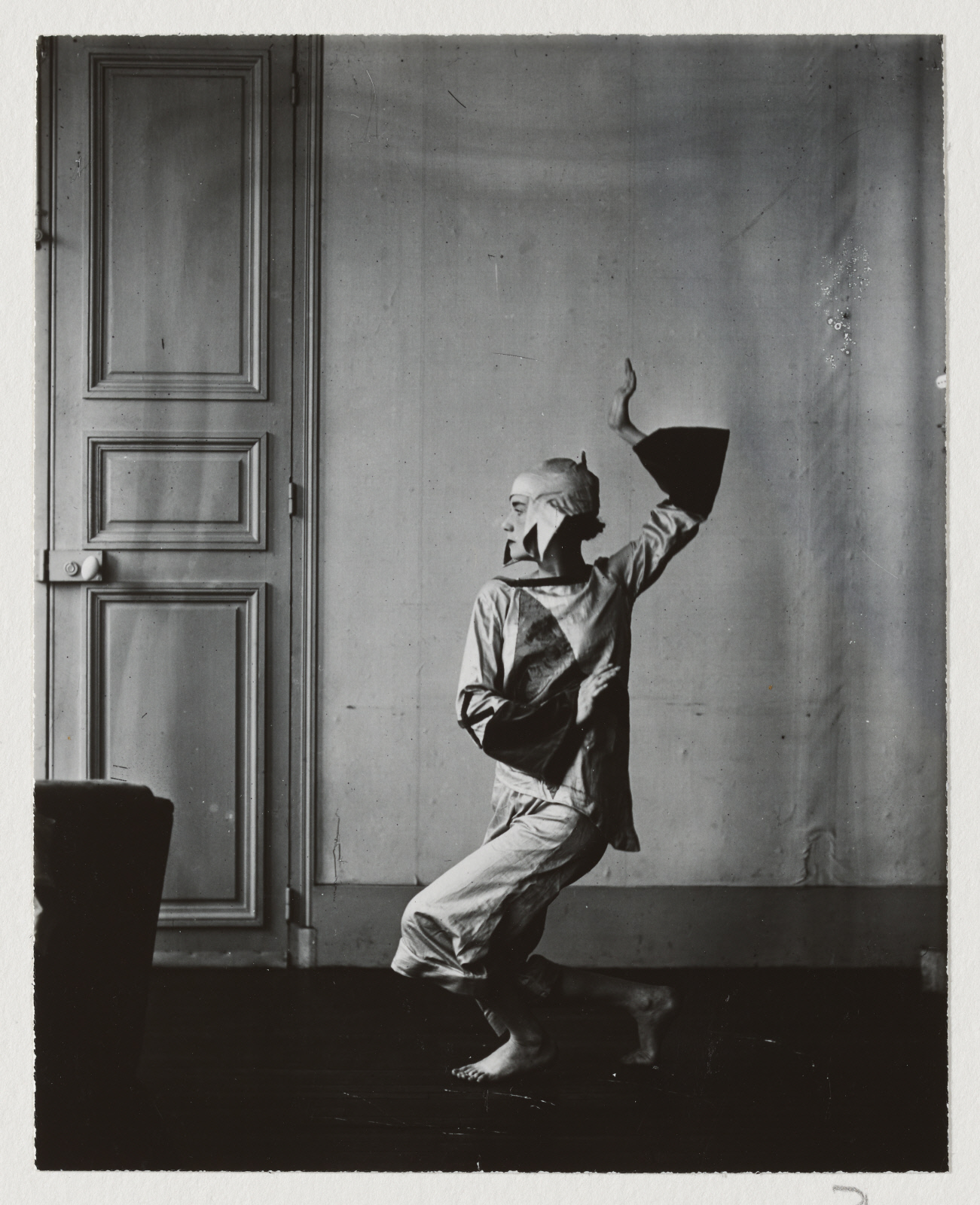

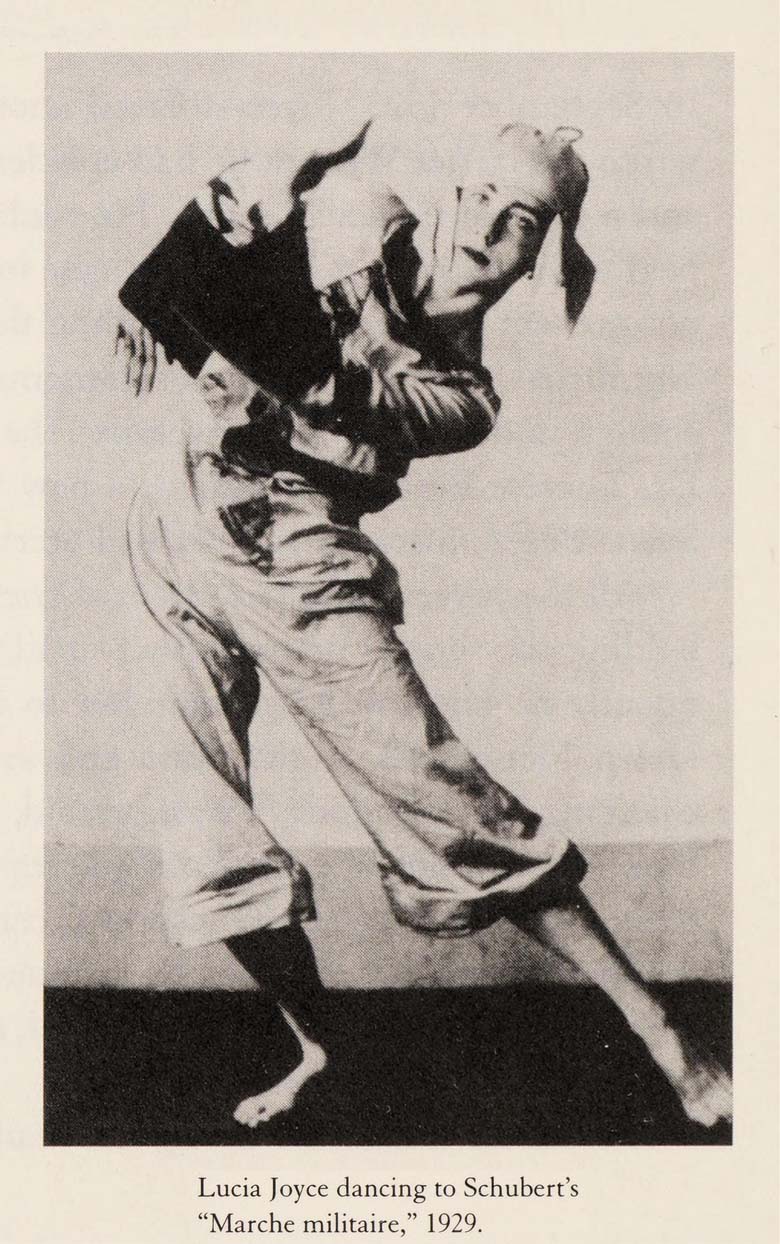

“Most accounts of James Joyce’s family portray Lucia Joyce as the mad daughter of a man of genius, a difficult burden. But in this important new book, Carol Loeb Shloss reveals a different, more dramatic truth: Lucia’s father not only loved her but shared with her a deep creative bond. His daughter, Joyce wrote, had a mind “as clear and as unsparing as the lightning.”” “Born at a pauper’s hospital in Trieste in 1907, educated haphazardly in Italy, Switzerland, and Paris as her penniless father pursued his art, Lucia was determined to strike out on her own. She chose dance as her medium, pursuing her studies in an art form very different from the literary ones celebrated in the Joyce circle and emerging, to Joyce’s amazement, as a harbinger of modern expressive dance in Paris. He described her then as a wild, beautiful, “fantastic being” who spoke to “a curious abbreviated language of her own” that he instinctively understood – for in fact it was his as well. The family’s only reader of Joyce’s work, Lucia was a child of the imaginative realms her father created. Even after emotional turmoil wreaked havoc with her and she was hospitalized in the 1930s, Joyce saw in her a life lived in tandem with his own.” “Though most of the documents about Lucia have been destroyed, Shloss has painstakingly reconstructed the poignant complexities of her life – and with them a vital episode in the early history of psychiatry, for in Joyce’s efforts to help his daughter he sought out Europe’s most advanced doctors, including Jung. Lucia emerges in Shloss’s account as a gifted, if thwarted, artist in her own right, a child who became her father’s tragic muse.”–Jacket, quoted from internet archive

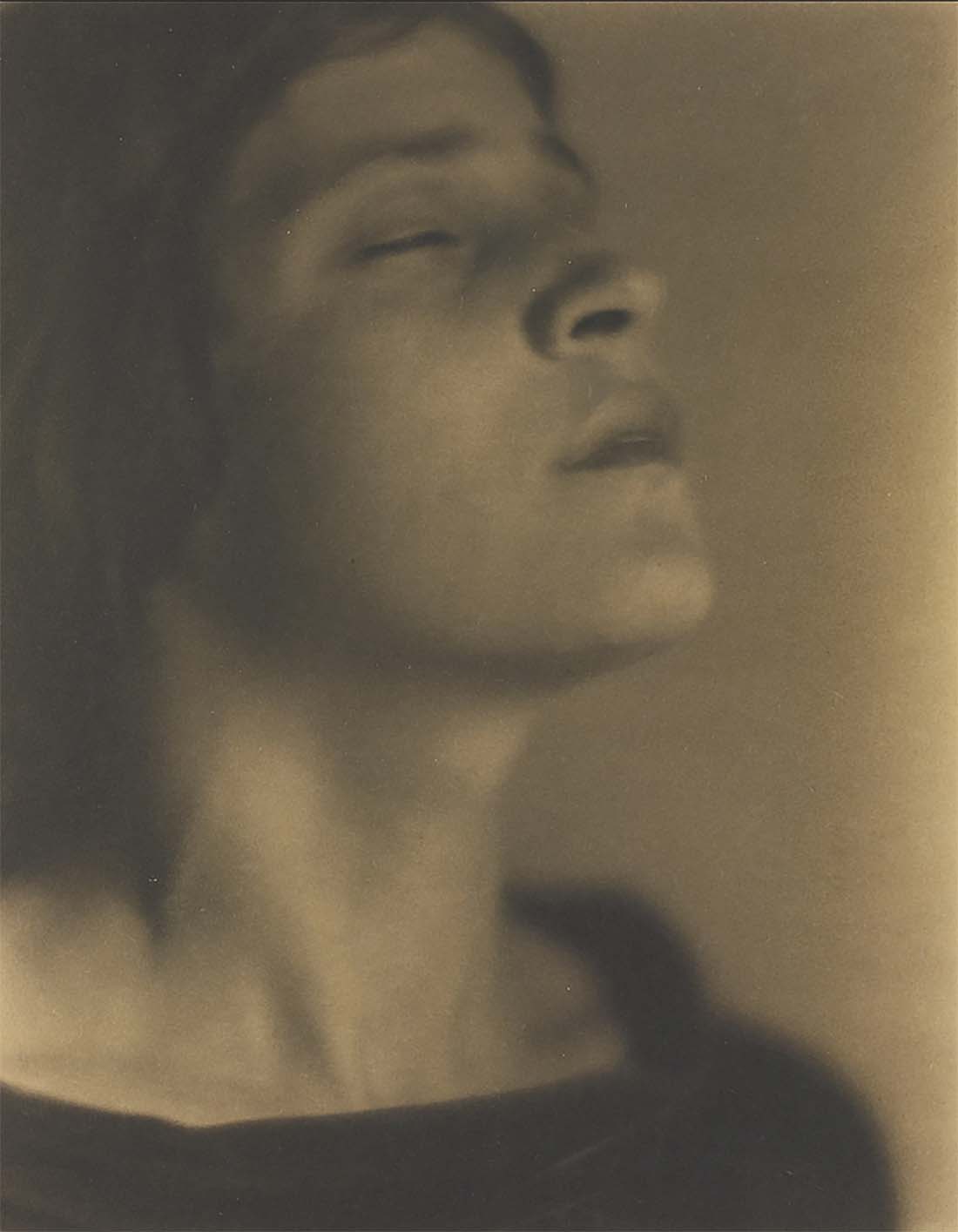

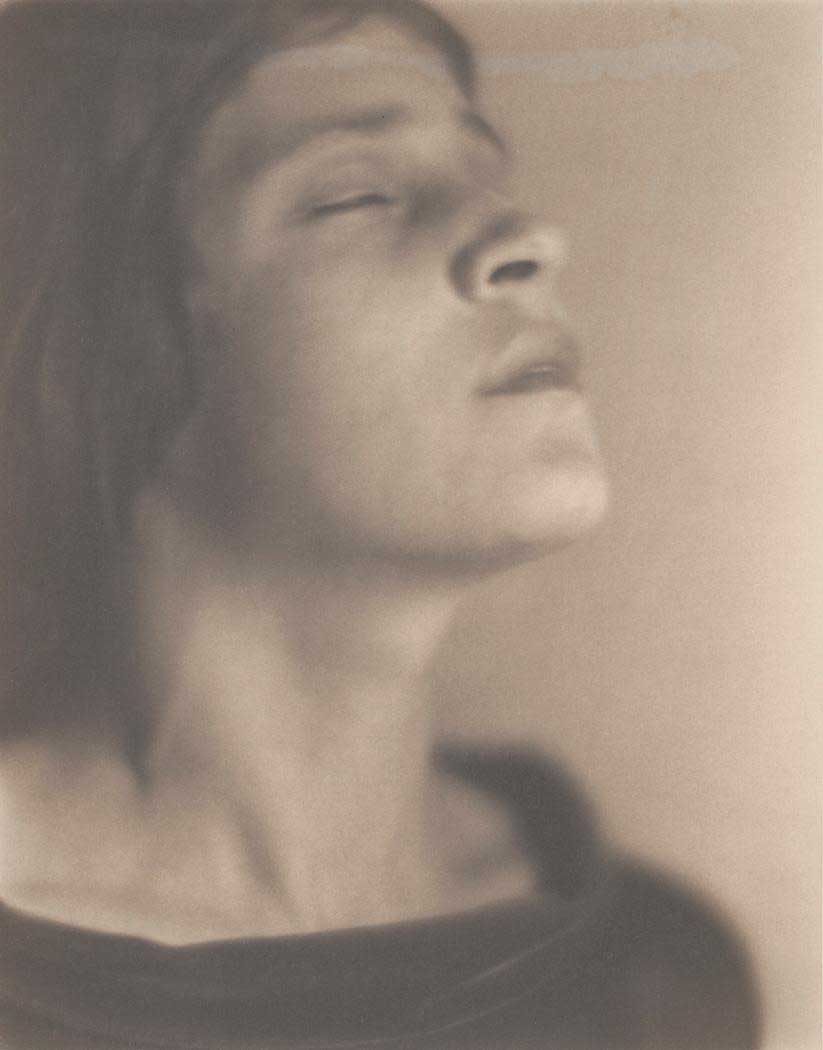

This photograph is among the earliest studies Edward Weston made of Tina Modotti, the woman whose face and figure would inspire some of Weston’s best work throughout the 1920s. The photographer regarded the image as an important one at the time, including it in two early exhibitions: in Amsterdam in 1922, and at the Aztec Land Gallery in Mexico City in 1923. This print is one of only three extant examples of this seminal picture of Modotti.

Head of an Italian Girl is from a series of studies and portraits of Modotti that Weston began in Los Angeles in 1921, soon after their love affair began, and would continue in Mexico. At the time this photograph was taken, each was married to someone else: Weston to the former Flora Chandler, the mother of his four children, and Modotti to the poet and textile designer, Roubaix de l’Abrie Richey. Born in Italy, Modotti was a recent arrival in Los Angeles, where she worked variously as an actress in silent films and as a seamstress and clothing designer. In the early 1920s, Weston made his living as a portrait photographer in Glendale, while pursuing his own creative work. The two fell in love shortly after they met, and Weston began photographing Modotti immediately. In April 1921, Weston wrote of Modotti to his friend, the photographer Johan Hagemeyer:

‘Life has been very full for me—perhaps too full for my good—I not only have done some of the best things yet—but have also had an exquisite affair . . . the pictures I believe to be especially good are of one Tina de Richey—a lovely Italian girl’ (The Archive, January 1986, Number 22, ‘The Letters from Tina Modotti to Edward Weston,’ p. 10)

In the present image, the ecstatic expression on Modotti’s face provides some indication of the intensity of their new relationship.

Amy Conger locates only two prints of this image, both in institutional collections: a palladium print originally owned by Johan Hagemeyer and now at the Center for Creative Photography, Tucson [view image below]; and a platinum print at the Baltimore Museum of Art. [quoted from source]

Dancer Áine Stapleton talks about her film Horrible Creature, a ‘creative investigation’ of the life of Lucia Joyce

I’ve been creatively investigating the biography of Lucia Joyce (daughter of the writer James Joyce) since 2014, through both choreography and film.

Lucia once commented to a family friend in Paris that she wanted to ‘do something’. She wanted to make a difference and to creatively have an impact on the world around her. Dancing was her way of having an impact. She trained hard for many years and worked with various avant-garde teachers including Raymond Duncan. She created her own costumes, choreographed for opera, entered high profile dance competitions in Paris, and even started her own dance physical training business after apprenticing with modern dance pioneer Margaret Morris.

Until this time she had lived almost entirely under the control of her family, and had to share a bedroom with her parents well into her teens. I imagine that dancing must have been a revolutionary feeling for her, and would have offered her an opportunity to process her chaotic and sometimes toxic upbringing. It was during these dancing years that she was finally allowed to spend some time away from her family, but this freedom did not last long. Her father’s artistic needs and his sexist disregard for her career choice interrupted her training at a vital stage. She was forced to stop dancing, and the circumstances surrounding this time remain unclear. I do not believe that she herself made the decision to quit dancing. Lucia was incarcerated by her brother in 1934, and then remained in asylums for 47 years. She died in 1982 and is buried in Northampton England, close to her last psychiatric hospital.

I’ve read Lucia’s writings repeatedly over the last four years, and my opinion of her hasn’t changed. She was a kind, funny, intelligent, creative and loving person. After her father James’ death in 1941, she had one visit from her brother and no contact from her mother, yet she only writes good things about her family. She was consistently thankful to those people who made contact with her during her many years stuck in psychiatric care. She appreciated small offerings from friends, such as an additional few pounds to buy cigarettes, a radio to keep her company, a new pair of shoes or a winter coat, all of which seemed to offer her some comfort in her later years.

I have no interest in romanticising Lucia’s relationship with her father. I also don’t believe that she was schizophrenic. I think that whatever mental strain Lucia experienced was brought on by those closest to her. Her supposed fits of rage or out of the ordinary behaviour only brought to light her suffering. We know that many women have been mistreated and silenced throughout history. Why do we still play along with a romanticised version of abuse? And why is James and Lucia’s relationship, or ‘erotic bond’ as Samuel Beckett described it, regarded as an almost tragic love story?

Horrible Creature (2020) examines Lucia’s story in her own words, and also focuses on the environment which shaped her during this time. The work attempts to tap into that invisible energy that can provide each of us with a real sense of aliveness and connectedness to the world around us, even in moments of great suffering.

Quoted from Raidió Teilifís Éireann, Ireland’s National Public Service Media