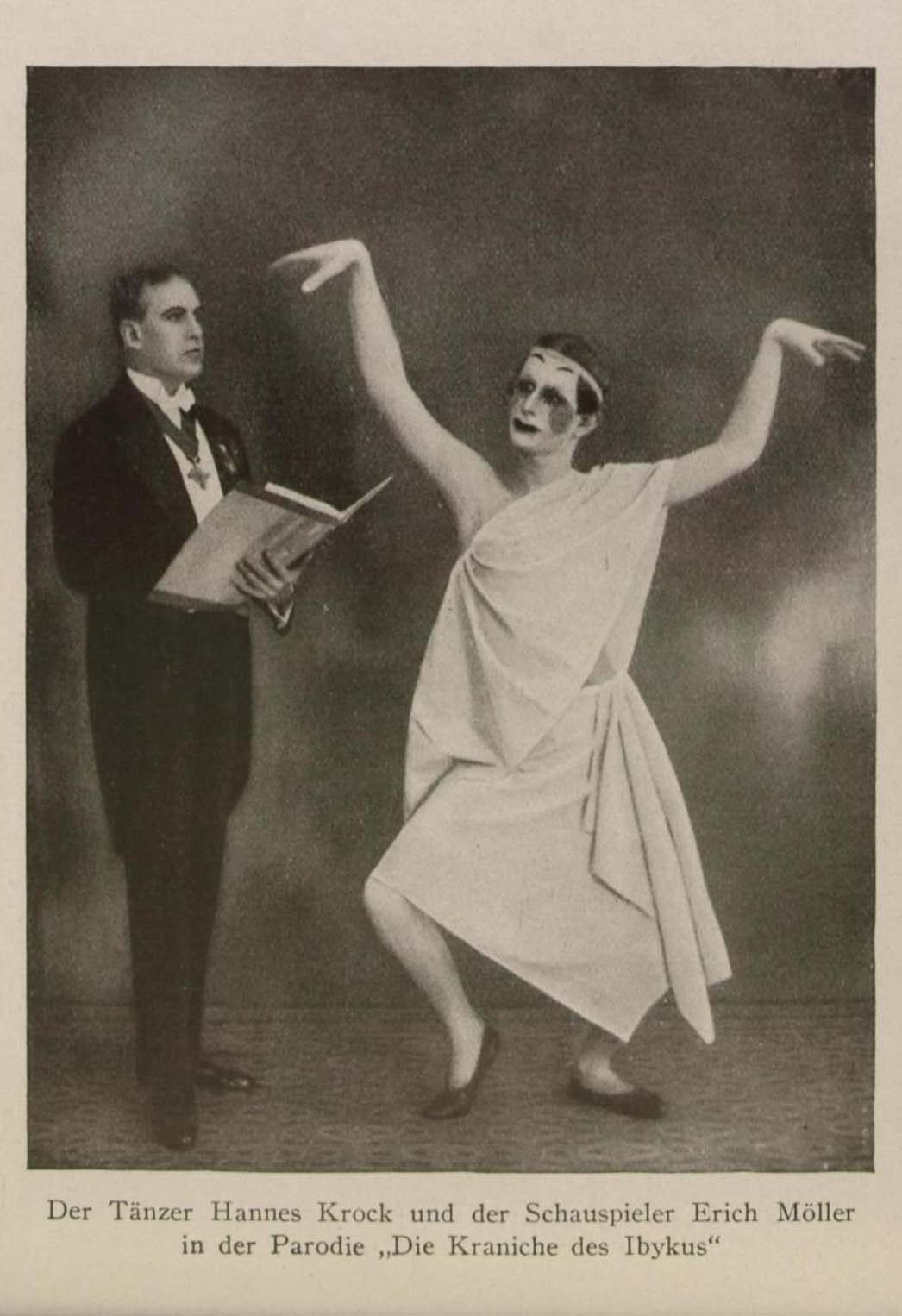

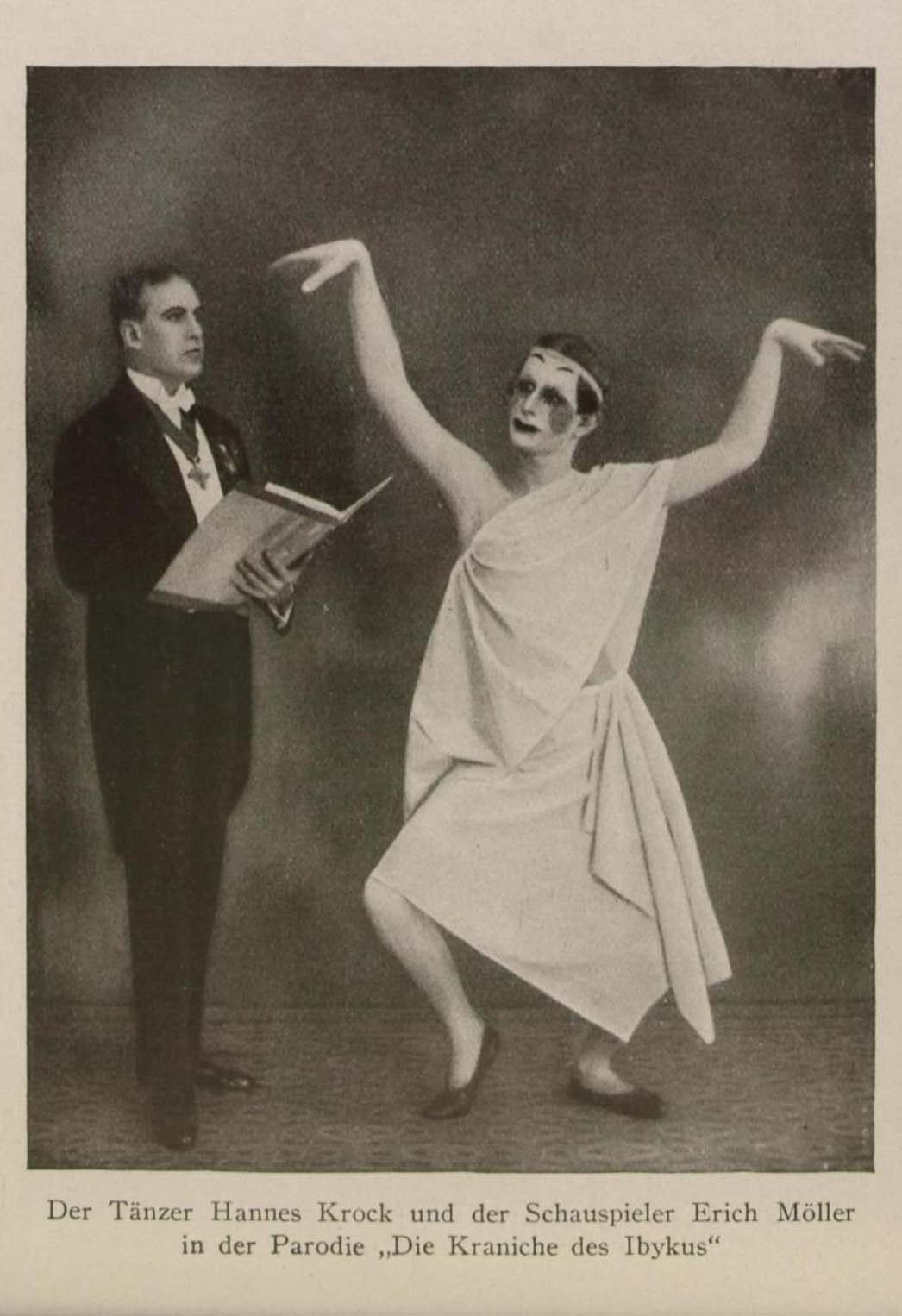

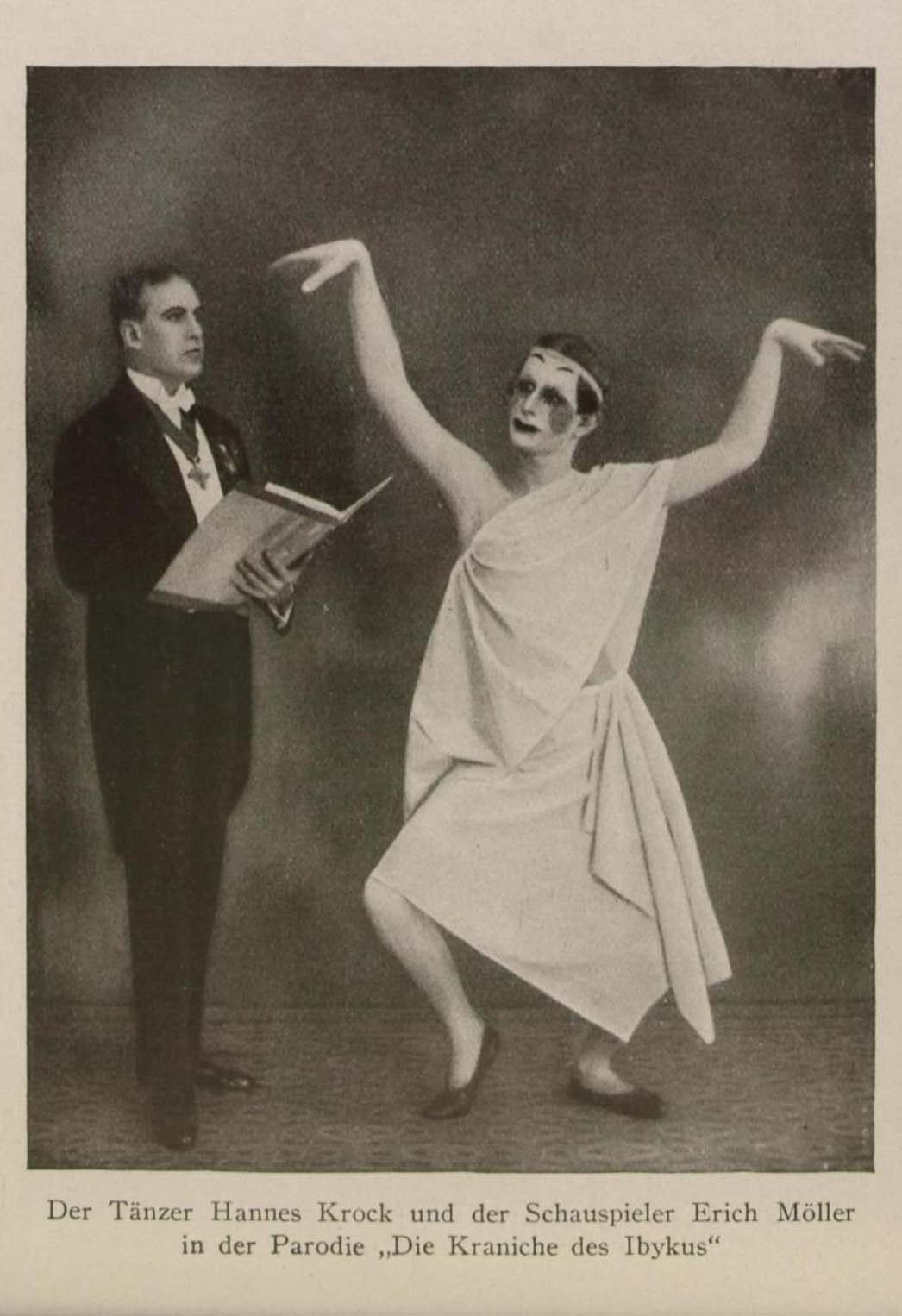

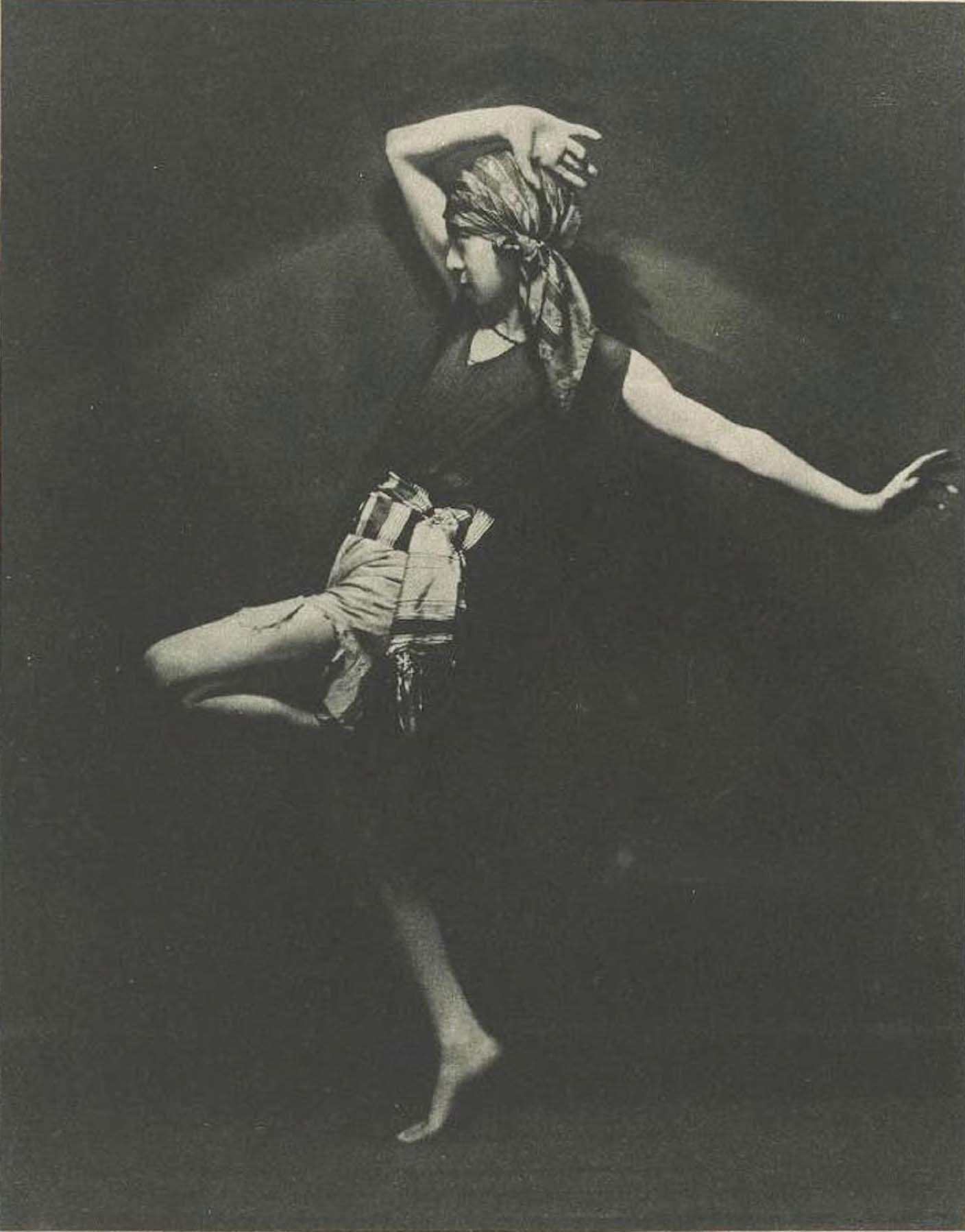

Parodistischer Tanz

images that haunt us

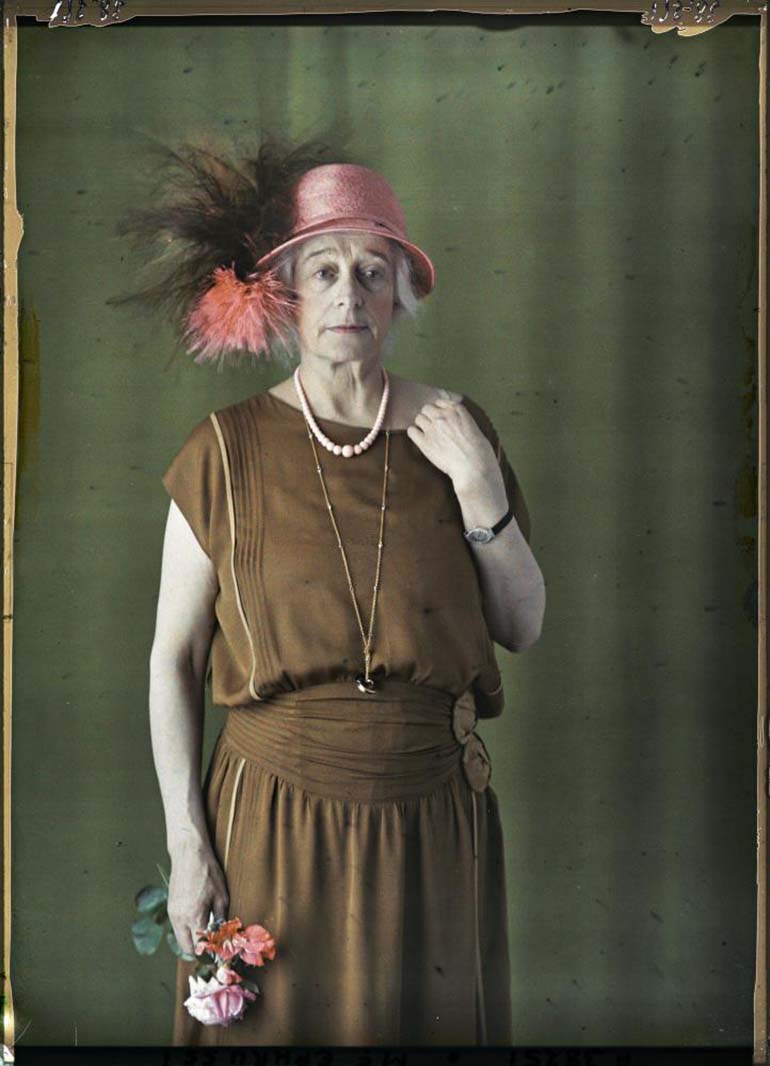

From : Die persönliche Note im Gesicht der modernen Frau • The personal touch on the face of the modern woman • Scherl’s Magazin, Band 4, Heft 11, November 1928.

![Studie der Tänzerin Fatma Carell von [Emil] Bieber. Revue des Monats Band 2, H.11, September 1928](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/revue-des-monats-band-2-h.11-september-1928-fatma-carell-crp.jpg)

An exhibition in the La Boverie Museum in Liège, Belgium, shows the hitherto little-known passion for collecting and love for art of the women of the Rothschild dynasty.

Since the 19th century, the Rothschild name has stood for success in the financial world, but also for intellectual and artistic wealth. The story of the family began in the Jewish ghetto of Frankfurt am Main. It was there that the coin dealer Mayer Amschel (1744-1812) began to rise to become one of the richest families in Europe. “Only” ten of 19 children survived with his wife Gutle Schnapper. While the daughters had no access to the company, the patriarch skillfully placed his five sons in London, Vienna, Paris and Naples, laying the foundation for a widespread family empire that made a name for itself primarily through banking. The financing of states and the granting of loans served as the business model for this. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, women pulled the strings.

Now an unusual exhibition is dedicated to them. In cooperation with the Louvre in Paris, the La Boverie Museum in Liège, Belgium, is presenting nine women from the French branch of the family dynasty who have distinguished themselves as donors, patrons and collectors. The biographies of the women, which are set in the last two hundred years, provide information about the respective Zeitgeist. “Many of the often overlooked Rothschild women were women of talent, spirit and conviction, key figures in cultural life as well as benefactors for numerous museums,” writes Louvre Director General Laurence des Cars in her catalog introduction. They bequeathed more than 130,000 works to French museums through donations or bequests.

A selection of 350 objects from around 30 French institutions and private collections now invites you to take a tour – which in relation to the museum design with artificial turf and false rose bushes sometimes seems kitschy. Paintings by Cézanne, Renoir and Delacroix, sculptures, jewelry and porcelain, furniture, African and Far Eastern art can be seen as well as – rather untypical for women – whistles and matchboxes. The latter were the favorite collector’s items of Alice de Rothschild (1847 Frankfurt/Main to 1922 Paris). You have to know that matches were still something special at that time. They were not industrially manufactured until 1832 and were even taxed in France from 1871 to improve public finances, which had been strained by the Franco-Prussian War. Rothschild’s boxes show decorations as everyday objects, some of which contained frivolous scenes.

Collecting as emancipation

Matchboxes were certainly one of the things that were relatively easy to collect 150 years ago. It was more difficult with art. In the 19th century, women were legally dependent on their father or husband. They had no right to private property. In the household they were responsible for the decoration. For example, James – one of the sons of Mayer Amschel, a star banker in Paris and married to his brother Salomon’s daughter – wrote in a letter: “The wife is an important part of the furniture”. After all, collecting decorative objects enabled women to achieve personal emancipation and at the same time legitimized their social position as patrons. However, more in the background than in public. In the Rothschild clan, the women were often only mentioned in the context of donations and purchases from their husbands, whose knowledge, specialization and profession were in the foreground.

With Alice’s niece, Béatrice de Rothschild (1864 Paris – 1934 Davos), a different type of woman moved into the social focus. Only a year after her separation (1904) from her husband Maurice Ephrussi, a billionaire of Russian descent, Béatrice inherited part of her father’s fortune. Enough to literally build on. The resolute woman in her mid-forties has a villa built in the Renaissance style on the southern French peninsula of Cap Ferrat, which puts everything that has gone before in the shade. She plans facades, gardens and interior design with her own hand and in an authoritarian manner. Standing in the Rothschild tradition, Béatrice is also an eclectic collector. She acquires paintings by French Impressionists and those from the 15th and 16th centuries. In addition, precious carpets, furniture and porcelain objects adorn their new home. In the end, she only lives in the house for a short time. In 1933, she bequeathed it and the art collection to the French Academy of Fine Arts with the desire to set up a museum there. [quoted (partially) from Kunst in Frauenhand – read more on Monopol Magazin]

![The gentle, inward gesture. The dancer Irmin von Holten. Photograph by Hans Robertson for the article: Die persönliche Note im Gesicht der modernen Frau [The personal touch on the face of the modern woman] by Werner Suhr published in Scherl's magazine in November 1928 (nº 4-11)](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/scherls-magazine-band-4-h.-11-november-1928-atelier-robertson.jpg)

The gentle, inward gesture. The dancer Irmin von Holten. Photograph by Hans Robertson for the article: Die persönliche Note im Gesicht der modernen Frau [The personal touch on the face of the modern woman] by Werner Suhr published in Scherl’s magazine in November 1928 (nº 4-11)

From : Die persönliche Note im Gesicht der modernen Frau • The personal touch on the face of the modern woman • Scherl’s Magazin, Band 4, Heft 11, November 1928.

Mrs. Tudor Wilkinson, born Kathleen Mary Rose (1893-1975), known as Dolores or Rose Dolores started to work for the fashion designer Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon around 1910. During the First World War, Duff-Gordon’s focus shifted to her New York office which she had opened in 1910. For her New York fashion shows she imported her own models from England, although Dolores was not among the first she brought over. The shows became so popular that she had to start holding them in a theater. It was probably at one such event around 1916 that Florenz Ziegfeld and his wife Billie Burke discovered Duff-Gordon’s designs and her model Dolores. Ziegfeld was enraptured by Dolores and the luxurious spectacle of the show and Burke ordered two of Duff-Gordon’s creations. Soon, Duff-Gordon was making costumes for Ziegfeld’s theatrical productions, the Ziegfeld Follies.

Ziegfeld decided to base a scene in his next Follies on one of Duff-Gordon’s fashion shows and to use Duff-Gordon’s girls to model the clothes. Dolores made her first appearance for Ziegfeld in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1917 in which she played the Empress of Fashion. In Midnight Frolic of 1919, Dolores played the part of The White Peacock in the Tropical Birds number (wearing the iconic peacock costume).

Rose Dolores was called “the loveliest showgirl in the world”. She had a laconic and androgynous beauty, and a haughty demeanor on stage that had been cultivated by Duff-Gordon and was naturally aided by Dolores’ height. Dolores, like the other former mannequins, was only required to walk and pose when on stage. It was said that she never smiled during an appearance. It was also said that Duff-Gordon had trained her to act like a Duchess.

Diana Vreeland commented, “I remember his [Ziegfeld’s] girls so vividly. Dolores was the greatest of them – a totally Gothic English beauty. She was very highly paid just to walk across the stage – and the whole place would go to pieces. It was a good walk I can tell you – it had such fluidity and grace. Everything I know about walking comes from watching Ziegfeld’s girls.”

In 1923, Dolores married the St. Louis art collector Tudor Wilkinson in Paris and retired from the stage. After her marriage, Dolores adopted the severe masculine style of dress and hair popular at that time, appearing in Eve, The Lady’s Pictorial in March 1925 [see picture below] in a suit jacket and tie. [partially quoted from wikipedia]

![Man Ray :: Die melancholisch Sensitive. [The melancholic sensitive] Renate Green. Scherl's magazine, Band 4, Heft 11, November 1928](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/scherls-magazine-band-4-h.-11-november-1928-man-ray-renate-green.jpg)