images that haunt us

![Jan Zeegers :: Marie Zeegers [daughter of the photographer], 1912. Autochrome. | Nederlands Fotomuseum Rotterdam](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/jan-zeegers-marie-zeegers-dochter-van-de-fotograaf-1912-c2a9-nerderlands-fotomuseum-rotterdam.jpg)

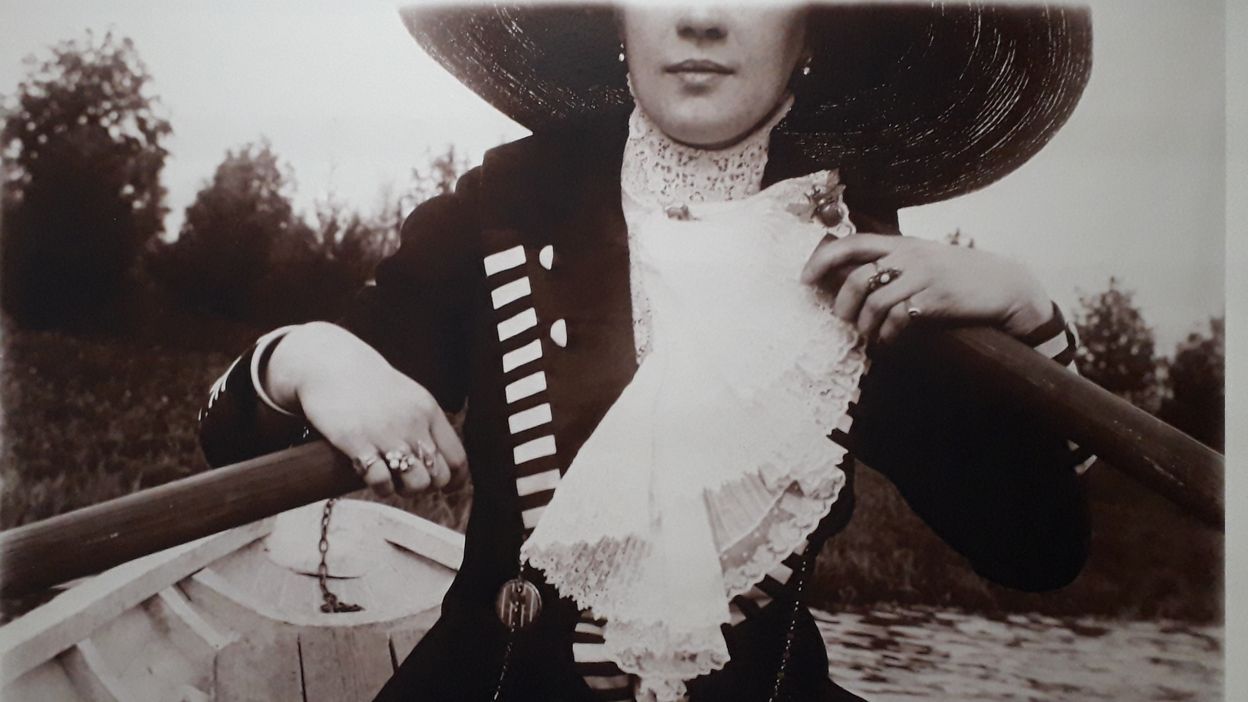

“This might be the first Dutch girl to have her picture taken in colour. The photographer, Jan Zeegers, was an Amsterdam textile merchant by trade, but this picture shows a definite eye for composition and colour – note the girl’s dress, the bow in her hair, and the cherries on the plate.” quoted from booklet of the exhibition guide: Gallery of Honour of Dutch Photography (June 2021)

When the autochrome — the Lumière brothers’ new colour photographic process — reached New Zealand in 1907, it was eagerly adopted by those who could afford to use it. Among them was Auckland photographer Robert Walrond, whose ‘Cleopatra’ in Domain cricket ground is among a small number of superb early colour photographs in Te Papa’s collection. The combined effect of the sun and wind on the women’s costumes and in the fluttering appearance of the silk scarf held above the Cleopatra character is stunning. The tableau is interrupted but undiminished by what appears to be a pipe band in uniform in the background. The women were very likely part of what was described by the New Zealand Herald as a ‘fine’ performance of Luigi Mancinelli’s Cleopatra (a musical setting of the play by Pietro Cossa), associated with the Auckland Exhibition of 1913–14 held in the Domain.

The story of Cleopatra — with a particular focus on her love life and tragic death — was an exotic but respectable theme for theatre and dress-up events for women at the time. The Cleopatra myth and look were popularised by international performers such as the frequently-photographed Sarah Bernhardt in France and by numerous stage productions and films from the late nineteenth century onwards. With the advent of photography, part of performing the role became having a portrait made while in costume. The arrival of the autochrome was greeted with excitement and anticipation because rich colours could now be captured and the elaborate style of the costumes enhanced.

Much was made of the impact the autochrome would have on art and the role of photography within it. However, one of the disadvantages of the process was that it involved a unique one-off image on a glass plate: this required projection to be viewed and couldn’t be exhibited. So despite the original excitement for the method, it slipped out of sight once new developments arrived that fixed colour printing on a paper format. Walrond’s set of autochromes held by Te Papa are one of only a few larger bodies of work by New Zealand practitioners of this process.

Lissa Mitchell – This essay originally appeared in New Zealand Art at Te Papa (Te Papa Press, 2018)

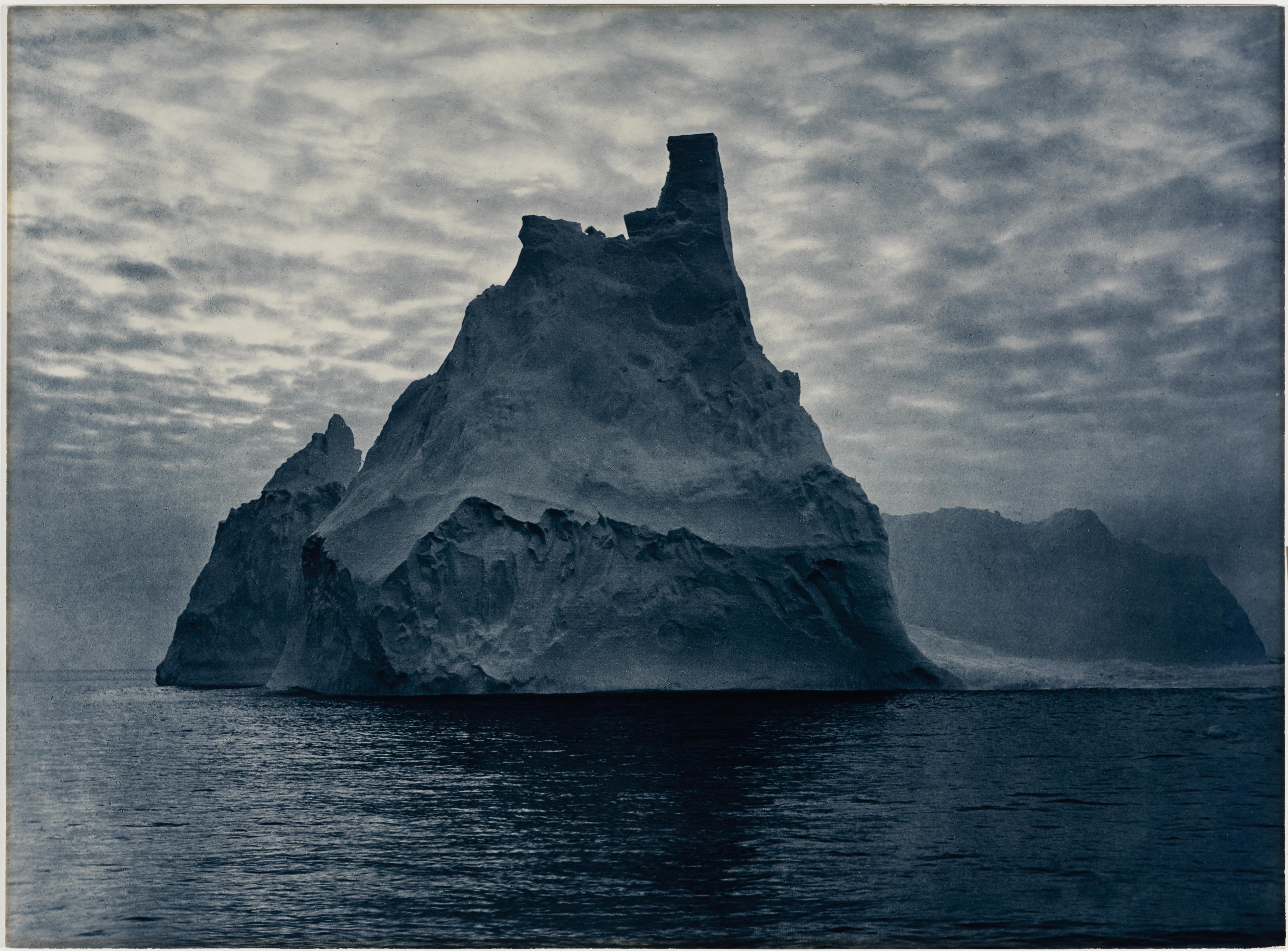

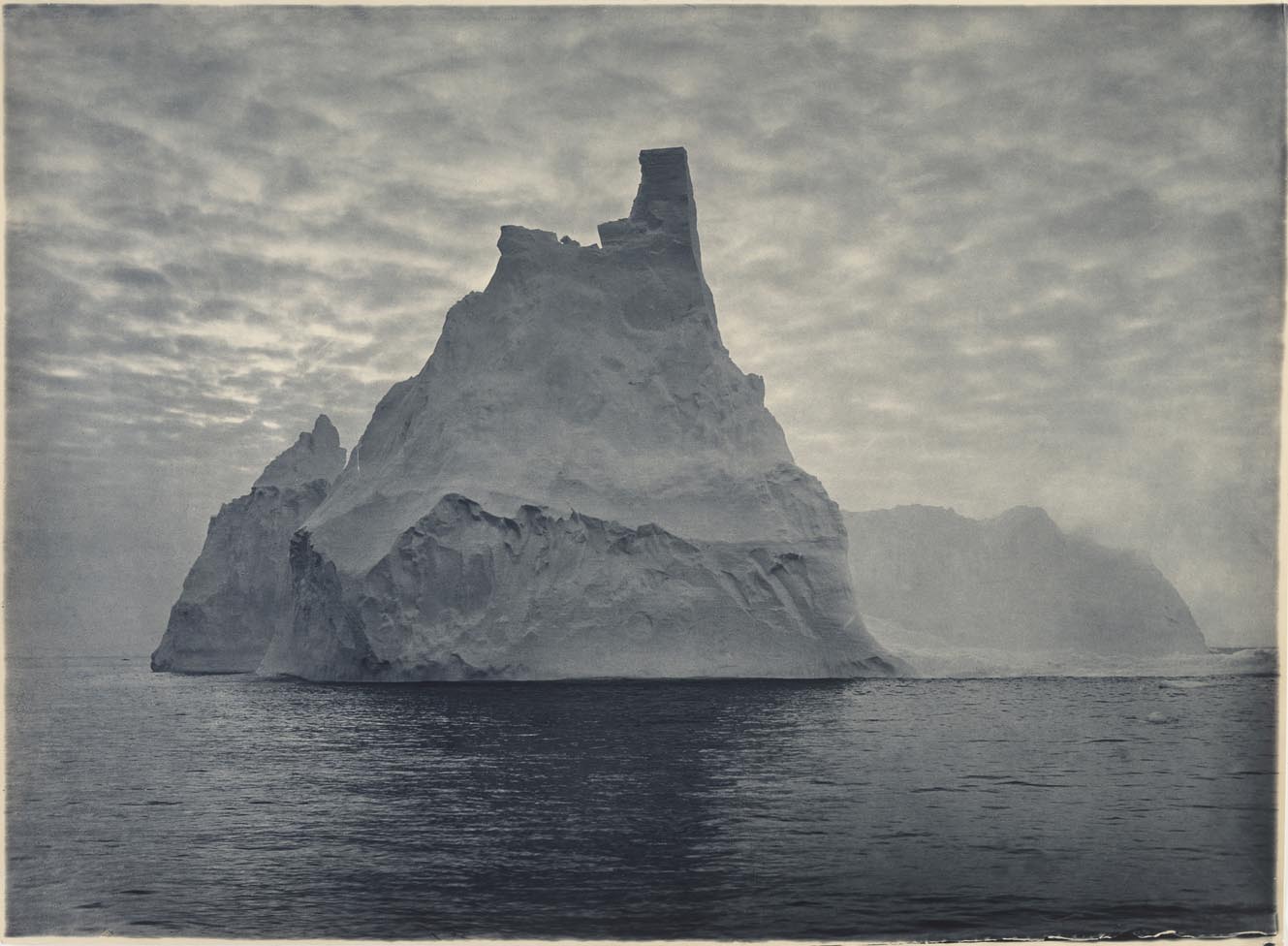

Gazing at the grey curtains of fog from the deck of our ship, so tiny in the surrounding vastness, we felt like Argonauts whose quest had led to the World’s brim. Slowly we crept on, filled with wonder and expectancy … Through a rift we made out the glimmering sheen of a colossal berg.

– Frank Hurley, Argonauts of the South (1925)

Thousands of mighty bergs were grounded on a vast shoal and our way lay through its midst. No grander sight have I ever witnessed among the wonders of Antarctica. We threaded a way down lanes of vivid blue with shimmering walls of mammoth bergs rising like castles of jade on either side. Countless blue canals branched off and led through what appeared to be avenues of marble skyscrapers – dazzling white in the full sunshine. Waves had weathered out impressive portals and gigantic caverns in their gleaming sides, azure at the entrance and gradually fading into rich cobalt in their remote depths. Festoons of icicles sparkling like crystal pendants, draped ledges and arches.

– Frank Hurley, Argonauts of the South (1925)

Among Hurley’s photographs taken on the Aurora in 1913 is A turreted berg, a striking study of a lofty iceberg. The photograph shows an iceberg that has been transformed by the elements into a floating pyramid of ice. In his writings, Hurley repeatedly refers to the intensity and purity of colour of the icebergs. In A turreted berg he has not employed the newly invented colour processes, but has made selective use of toning chemicals to alter the colour of the carbon photograph.15 In this case the normally neutral tonal range of this kind of photograph has been shifted to an intense shade of blue, this colour reflecting more naturalistically the actual tones of the subject.

– Susan van Wyk: A turreted berg : an Antarctic photograph by Frank Hurley [quoted from the National Gallery of Victoria]

It is interesting to note the sky in Hurley’s photograph. The clouds fan out almost symmetrically from behind the iceberg, whose remarkable silhouette is softly backlit. However, what seems to be a most fortuitous conjunction of natural phenomena is, in fact, a manipulated effect. Close examination of the photograph reveals an artificially crisp contour line around the iceberg – evidence that suggests Hurley manipulated the image in his darkroom, using the technique of masking, and combining negatives, to create a composite photograph. Hurley was well known for such practices in his work. Subsequently, the practice of combining negatives to create a photograph that ‘more accurately’ represented a scene entered the debate surrounding the veracity of photography as a documentary medium. But in 1913 this question of veracity does not appear to have been an issue, at least for Douglas Mawson, for whom Hurley was ‘indisputably a superb photographer, and a very competent technician in the way he superimposed different photographs for effect’.

– Susan van Wyk: A turreted berg : an Antarctic photograph by Frank Hurley [quoted from the National Gallery of Victoria]