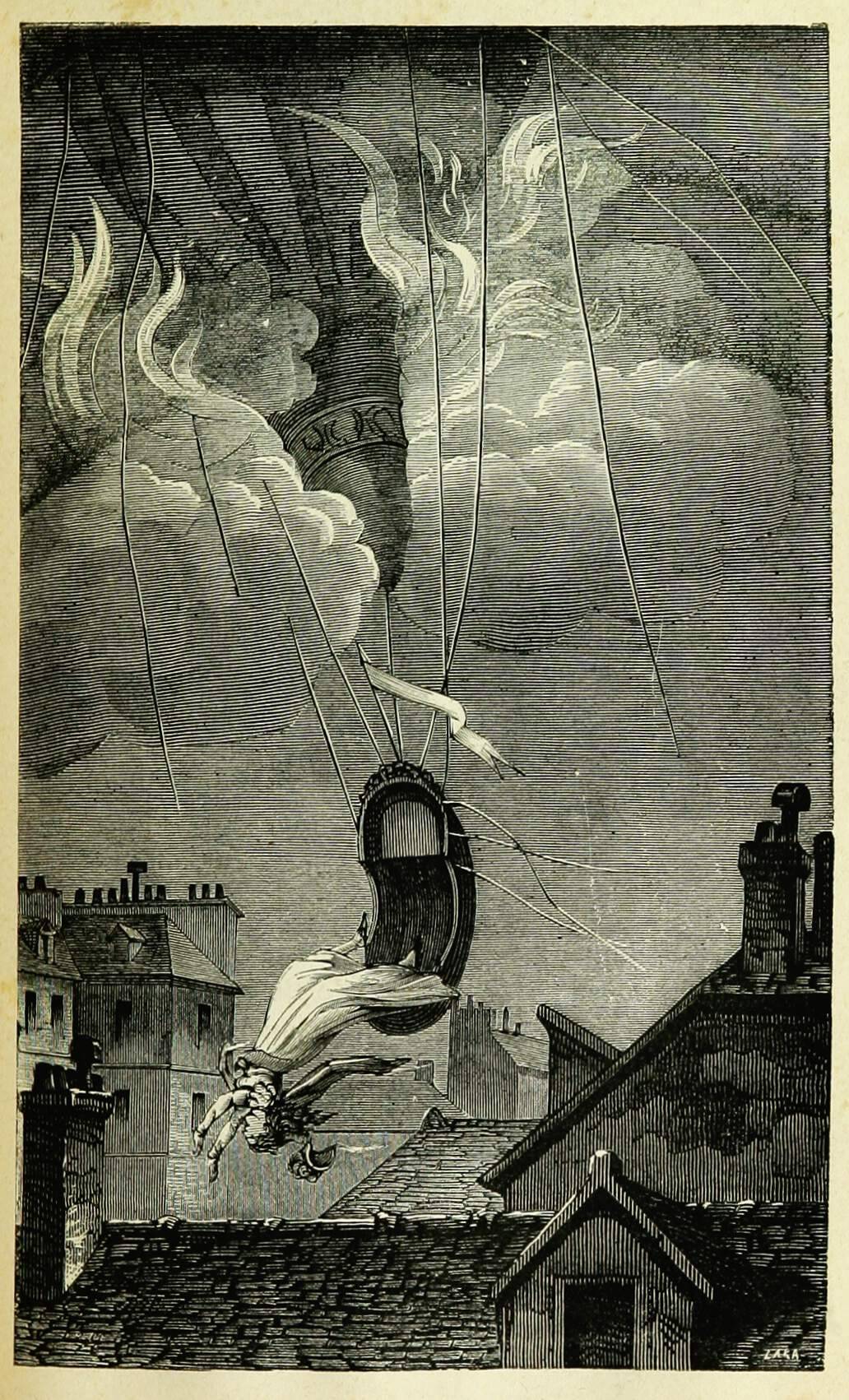

A woman is falling from the gondola of a hot-hair balloon flying over the roofs. She is Sophie Blanchard was the widow of aeronaut Pierre Blanchard, and an aeronaut herself.

On July 6, 1819, Madame Blanchard was taking part in an exhibition in the Tivoli garden in the rue Saint-Lazare. She carried with her a parachute full of fireworks in order to give the public the spectacle of fireworks descending from the middle of the air. She held a fire lance in her hand to light the fireworks she was supposed to launch from the balloon gondola. A false movement brought the orifice of the balloon into contact with the fire lance: the hydrogen gas ignited. Immediately an immense pillar of fire rose above the machine. Madame Blanchard was then distinctly seen trying to extinguish the fire by compressing the lower orifice of the balloon: then, recognizing the uselessness of her efforts, she sat down in the basket and waited. The gas burned for several minutes, without communicating with the balloon gondola. The rapidity of the descent was very moderate, and there is no doubt that, had she been directed towards the country, Madame Blanchard would have reached land without accident. Unfortunately it was not so: the balloon fell on Paris; it fell on the roof of a house in the rue de Provence. The gondola slid down the slope of the roof, on the side of the street. “A moi!” cried Madame Blanchard. These were her last words. As it slid down the roof, the gondola encountered an iron spike; it stopped abruptly, and, as a result of this shock, the unfortunate aeronaut was thrown out, and fell, head first, on the pavement. (quoted from scanned book at internet archive)

The caption reads in the original French: “Mort de madame Blanchard”.

IA