Mission : Léon Busy en Indochine; all images from Musée départamental Albert Kahn

images that haunt us

Mission : Léon Busy en Indochine; all images from Musée départamental Albert Kahn

Musée départamental Albert Kahn. Archives de la Planète. Opérateur : León Busy (x)

Musée départamental Albert Kahn. Archives de la Planète. Opérateur : Auguste Léon (x)

The draught of air caught the dancer, and she flew like a sylph just into the stove to the tin soldier. [The Tin Soldier and the Dancer ~ The Brave Tin Soldier ~ The Hardy Tin Soldier (1838)]

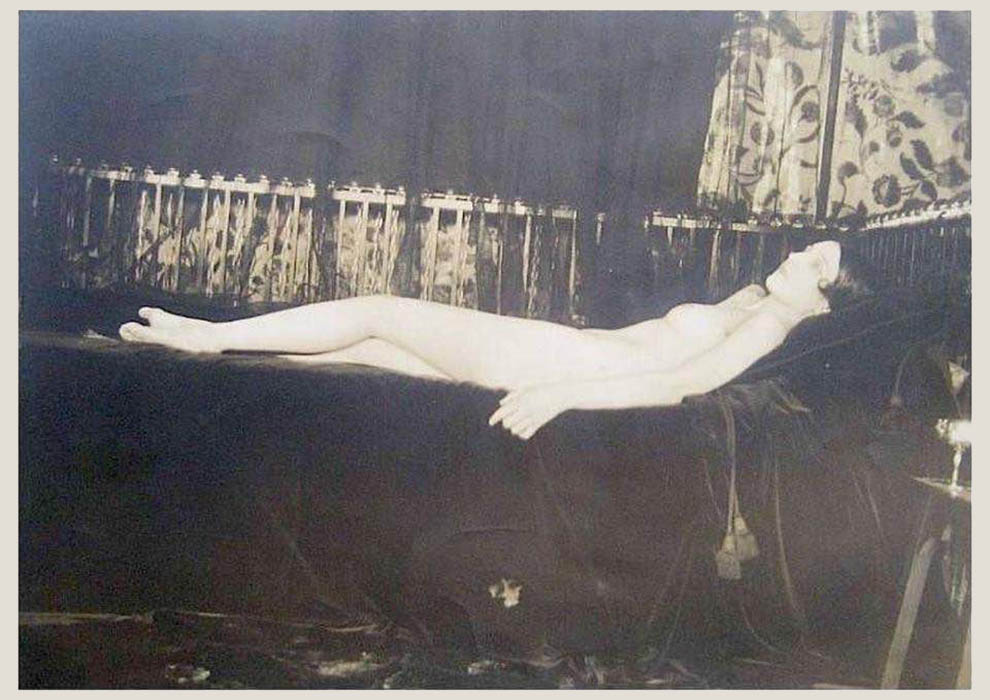

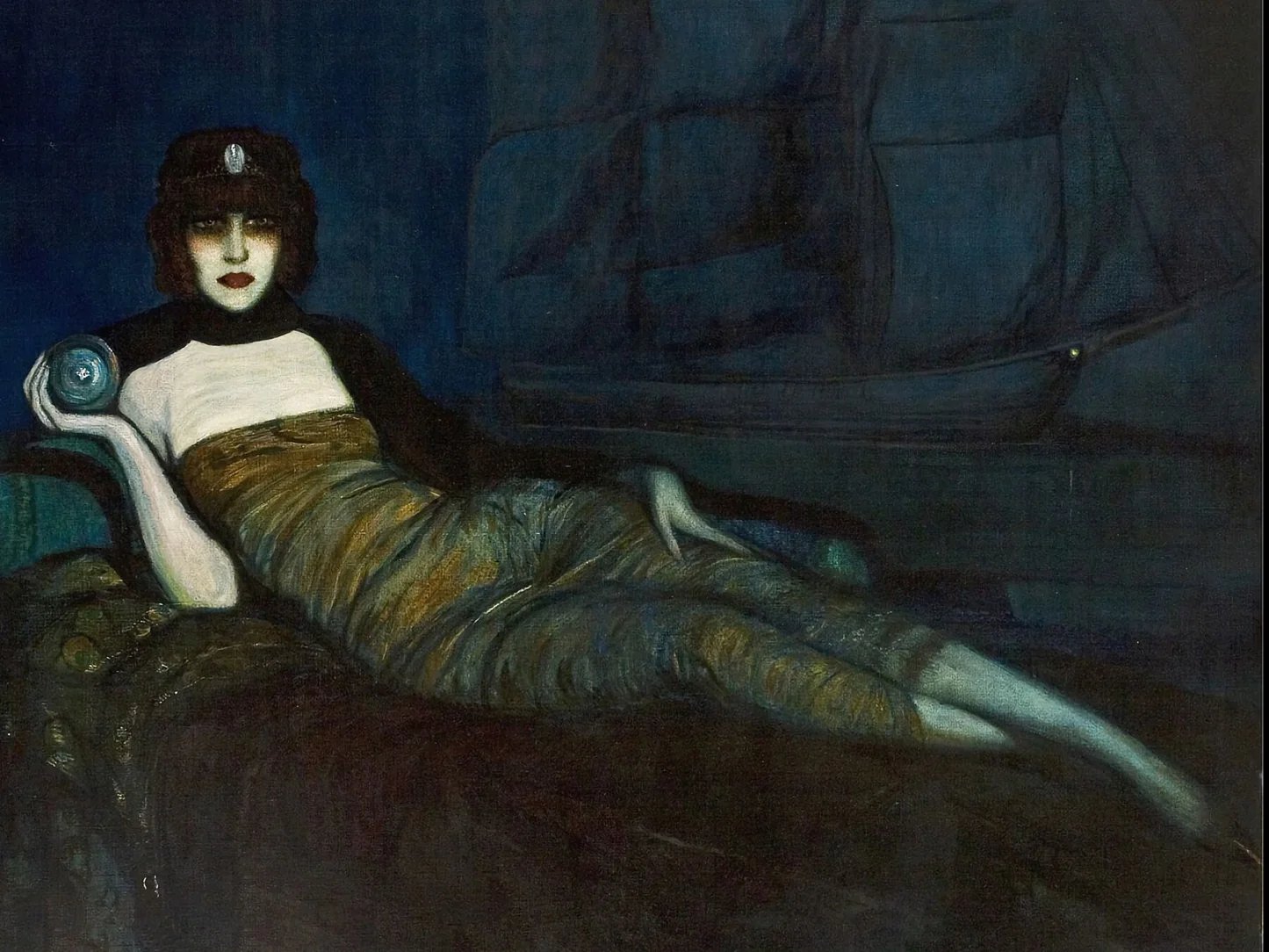

Brooks painted Ida Rubinstein more often than any other subject; for Brooks, Rubinstein’s “fragile and androgynous beauty” represented an aesthetic ideal. The earliest of these paintings are a series of allegorical nudes. In The Crossing (also exhibited as The Dead Woman), Rubinstein appears to be in a coma, stretched out on a white bed or bier against a black void variously interpreted as death or floating in spent sexual satisfaction on Brooks’ symbolic wing. (x)

In 1910, Brooks had her first solo show at the Gallery Durand-Ruel, displaying thirteen paintings, almost all of women or young girls. Among them, Brooks included two nude studies: The Red Jacket, and White Azaleas, a nude study of a woman reclining on a couch. Contemporary reviews compared it to Francisco de Goya’s La maja desnuda and Édouard Manet’s Olympia. But, unlike the women in those paintings, the subject of White Azaleas looks away from the viewer; in the background above her is a series of Japanese prints. (x)

Romaine Brooks remained aloof from all artistic trends, painting, in her palette of black, white, and grays, haunting portraits of the blessed and the troubled, of socialites and intellectuals. She moved in brilliant circles and, while resisting companionship, was the object of violent passions. […] Her story and her work reveal much about bohemian life in the early twentieth century.

Elizabeth Chew Women Artists at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (x)

Describing herself as a lapidée (literally: a victim of stoning, an outsider), at the height of her career Brooks was prominent in the intellectual and cosmopolitan community that moved between Capri, Paris and London in the early 1900s. Brook’s best known images depict androgynous women in desolate landscapes or monochromatic interiors, their protagonists undeterred by our presence, either staring relentlessly at us or gazing nonchalantly past. Her subjects of this time include anonymous models, aristocrats, lovers and friends, all portrayed in her signature ashen palette. Rejecting contemporary artistic trends such as cubism and fauvism, Brooks favoured the symbolist and aesthetic movements of the 19th century, particularly the work of James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Her ability to capture the expression, glance or gaze of her sitters prompted critic Robert de Montesquiou to describe her, in 1912, as ‘the thief of souls’. quoted from Frieze

All illustrations are from : The Rhinegold & The Valkyrie by Richard Wagner (1813-1883). Illustrations by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). Published in 1910. New York Public Library at internet archive

You could spend hours marveling at Arthur Rackham’s work. The legendary illustrator, born on September 19, 1867, was incredibly prolific, and his interpretations of Peter Pan, The Wind in the Willows, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Rip Van Winkle (to name but a few) have helped create our collective idea of those stories.

Rackham is perhaps the most famous of the group of artists who defined the Golden Age of Illustration, the early twentieth-century period in which technical innovations allowed for better printing and people still had the money to spend on fancy editions. Although Rackham had to spend the early years of his career doing what he called “much distasteful hack work,” he was famous—and even collected—in his own time. He married the artist Edith Starkie in 1900, and she apparently helped him develop his signature watercolor technique. From the publication of his Rip Van Winkle in 1905, his talents were always in high demand.

He had the advantage of a canny publisher, too, in William Heinemann. Before the release of each book, Rackham would exhibit the original illustrations at London’s Leicester Galleries, and sell many of the paintings. Meanwhile, Heinnemann had the notion to corner multiple markets by releasing both clothbound trade books and small numbers of signed, expensively bound, gilt-edged collectors’ editions. When the British economy flagged, Rackham turned his attention to Americans, producing illustrations for Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and later Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination.

Pragmatic he may have been, but Rackham’s detailed work is pure fantasy, alternately beautiful, romantic, haunting, and sinister. Nothing he did was ever truly ugly, although he could certainly communicate the grotesque. And his illustrations are never cute, although his animals—as in The Wind in the Willows—have a naturalist’s vividness, and he could do whimsy (think Alice in Wonderland, or his many goblins) with the best of them. Several generations of children grew up with this nuanced beauty; it’s probably wielded even more of an aesthetic influence than we attribute to it.

Rackham once said, “Like the sundial, my paint box counts no hours but sunny ones.” This is peculiar when one considers the moodiness of much of his palate, and the unflinching darkness of many of his illustrations. I think, rather, of a quote from his edition of Brothers Grimm: “Evil is also not anything small or close to home, and not the worst; otherwise one could grow accustomed to it.” He made that evil beautiful, too, and it was this as much as anything that enchanted. By Sadie Stein for The Paris Review Blog