images that haunt us

The Golden Potlatch was a city-wide festival held in July organized by civic boosters hoping to capitalize on the success of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909. The event continued for each of the next three summers before being suspended during wartime, and then was started up again as the Potlatch Festival from 1934 to 1941.

The name “Golden Potlatch” appropriates a Chinook Jargon word describing a Native ceremony of celebration and gift giving. It also reflects the importance of the Klondike gold rush to Seattle’s growth. Many organizers and participants in the Golden Potlatch dressed in stereotyped imitations of traditional Native attire, as part of a created Potlatch myth. The appropriation of Native culture in order to market products or events was one common example of discrimination and marginalization faced by Native peoples in the United States. Text quoted from University of Washington

Description of the Golden Potlatch festival: “The success of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition encouraged local boosters to plan another ambitious event to showcase the city. The Seattle Chamber of Commerce, the Advertising Club and the Press Club decided to create a civic celebration loosely modeled on the Northwest coastal Indian tribes’ potlatch, a ceremony of friendship and sharing. Seattle held its first Potlatch in 1911, but the Golden Potlatch of 1912 was a far greater festival, meant to attract visitors from far and near… The summer carnival was both a cynical exploitation and a madcap spectacle. The Potlatch shamelessly looted the heritage of Pacific Northwest Indian people. The Golden Potlatch began with the arrival of the ‘Hyas Tyee’ — or Big Chief — in his great war canoe, visiting the city from his home in the far north. The Tillikums of Elttaes (Seattle spelled backward) paraded the streets in white suits, their hats draped in battery-powered lights, glad handing any visitors who came their way. Bright-eyed members of the Press and Ad clubs, as well as the Chamber, slathered themselves in greasepaint, donned Chilkat blankets and pretended to be ‘tyees’ and ‘shamans.’ But the Golden Potlatch volunteers also offered a week of entertainment free to anyone in the city. Every day there was a different parade downtown — of the fraternal orders, the labor unions, the soldiers and sailors, or Seattle’s children. Daredevils flew ‘hydroplanes’ over Elliott Bay, and warships from the U.S. Pacific fleet anchored in the harbor.”(“‘Seattle Spirit’ soars on hype.” Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy, Seattle Times, March 10, 1996) quoted from Seattle public library

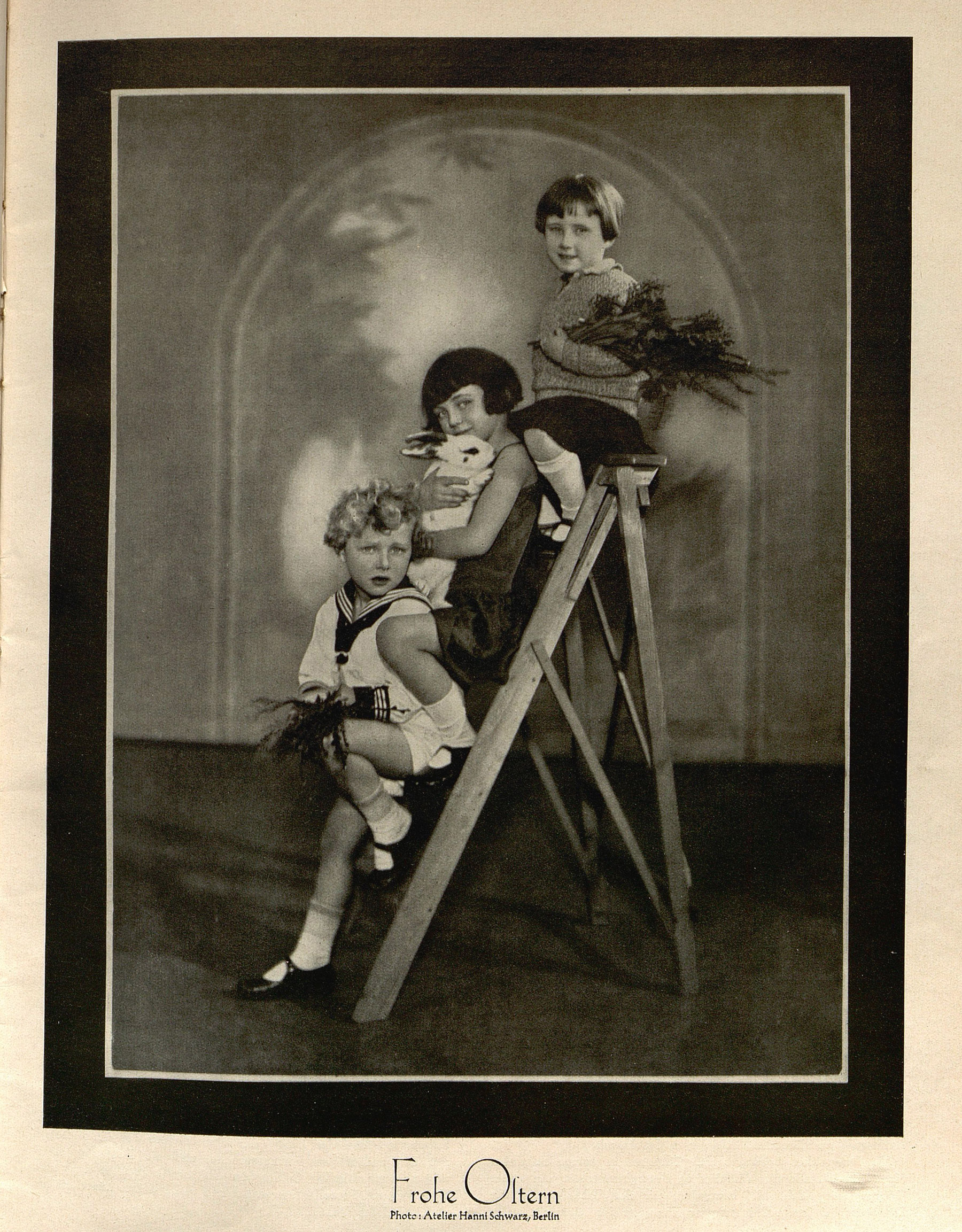

‘(…) Sunday 8th- Very nice day. Carnival’s burial. (…) Pepe went hunting and I dressed up as a man having a succès d’estime. Pepe came a little later and I decked him out with a dress of mine, Porota wore her paper suit and after dressing up granddaddy ridiculously, we devoted ourselves to perpetuate the memory of our joke through photography. As the audience, all the people from the kitchen, Luis, his wife, his children and even the workman celebrating the scene (…)’. Diary 4, p. 257 and 258, March 1908

Josefina Oliver (1875-1956) began as a vocational photographer among her friends in 1897. Two years later, she takes the first one of her one hundred self-portraits and photographs her friends and relatives, houses’ interiors and landscapes in the family farm in San Vicente. Josefina, a common porteña, was almost invisible. Author of a luminous ouvre, hidden until 2006, as a consequence of a society that disregarded women’s inner self.

Josefina Oliver reflects this reality in her artistic work so far composed by 20 volumes of a personal diary, more than 2700 photographs, collages and postcards. Plenty of her shots are conceived with scenographies; she always develops them and paints the best copies with bright colors. She makes up twelve albums, four of them are wonderful and only have illuminated photographs. At the same time, a transversal humor appears behind her multiform ouvre.

quoted from Josefina Oliver

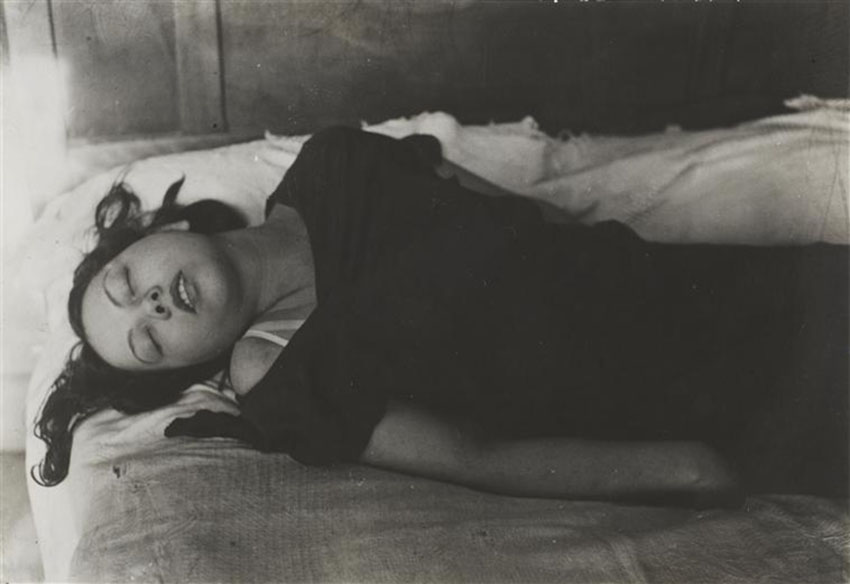

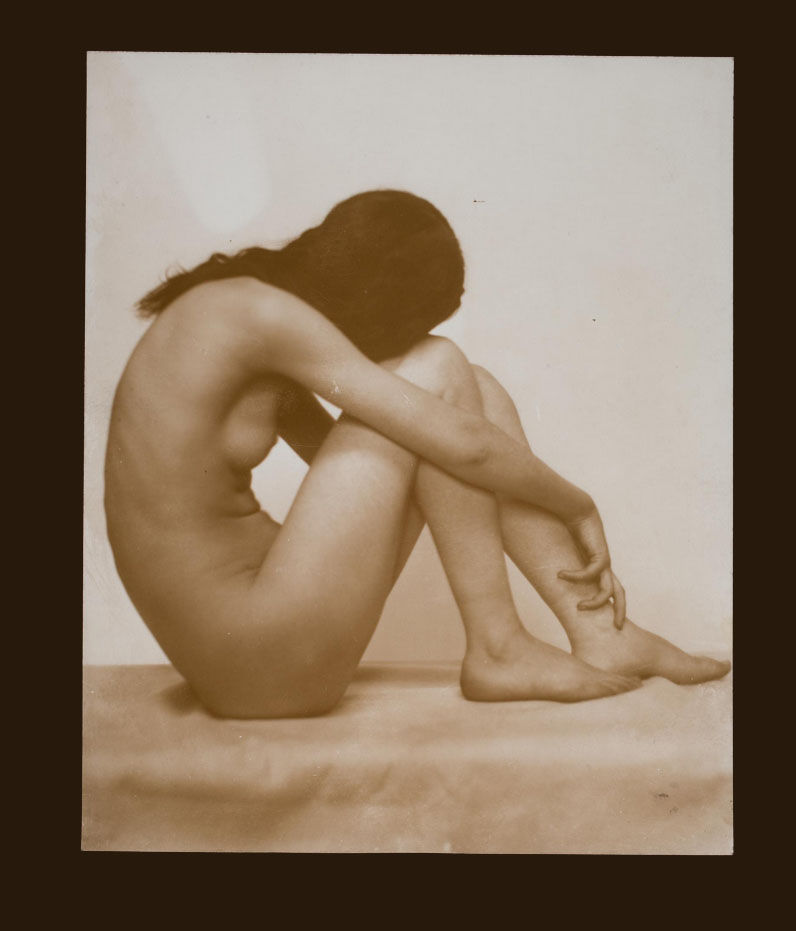

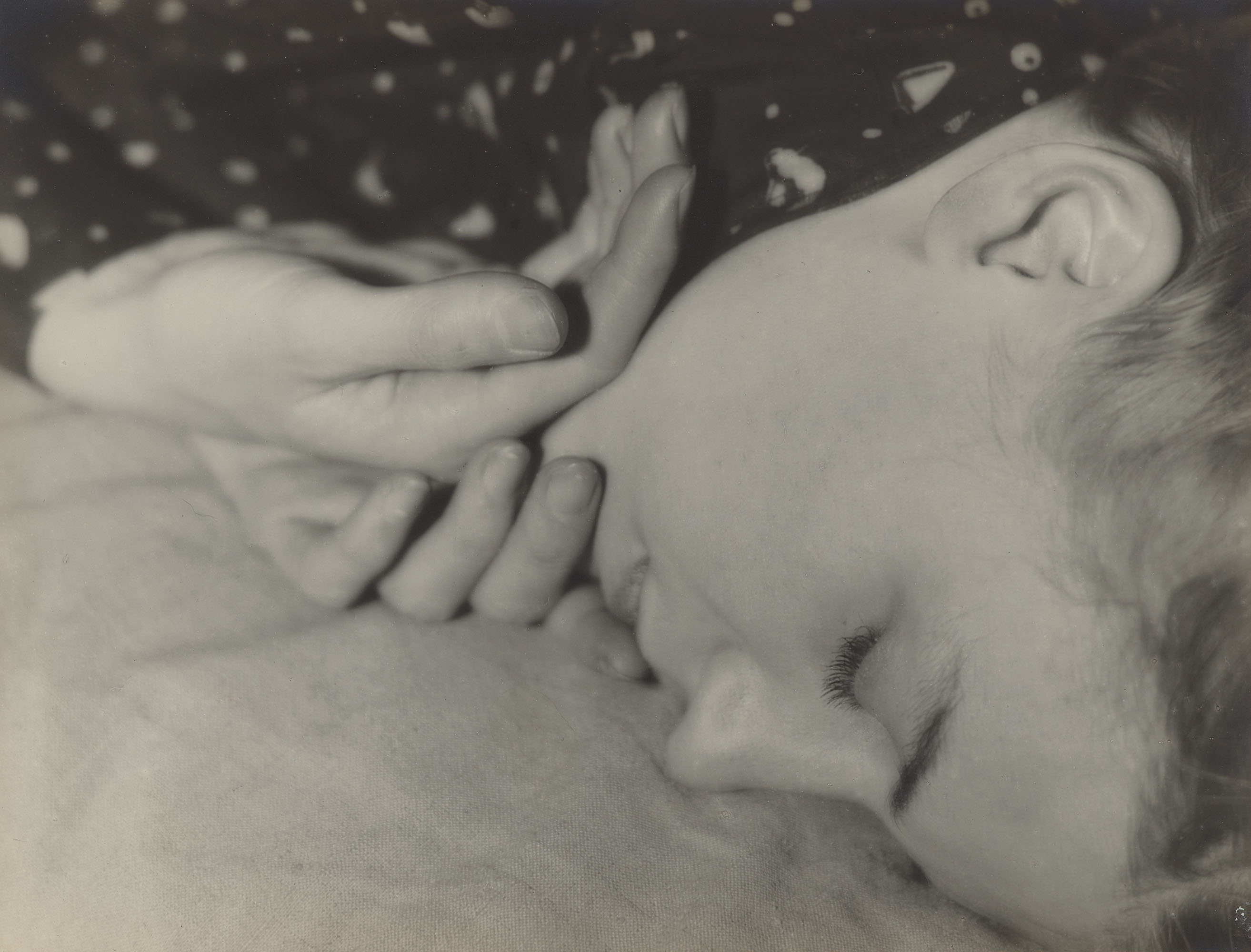

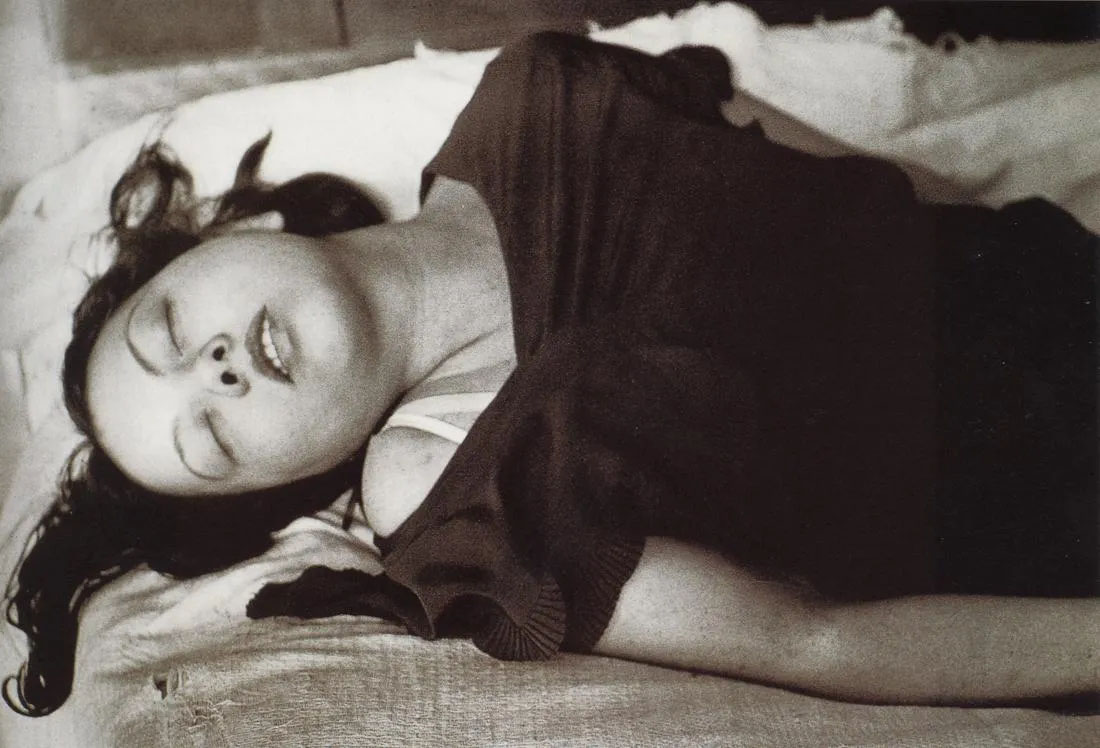

The Phenomenon of Ecstasy, is a photomontage built in a spiral: it is made up of 32 photos organized in a labyrinth of photos which wind up, drawing the eye in a hypnotic way towards the central photo, a portrait of a woman by Brassaï. This photo was part of a series of «femmes en jouissance onirique» (women in dreamlike enjoyment), taken in 1932.

Dalí saw in the convolutions of Art Nouveau a form of madness or intoxication. Brassaï’s portrait of the “overthrown” woman fit perfectly with his point. It therefore logically lands at the heart of a system which functions like a puzzle.

The historian Michel Poivert in his analysis of «Le phénomène de l’extase» ou le portrait du surréalisme même (1997) first lists the elements that make up the image: “most of them show a woman’s face that the title invites us to consider in ecstasy. In addition to these female faces, there are three male heads, four sculptures, two objects (a chair, a pin) as well as sixteen ears. These ear photos were taken by Alphonse Bertillon who was a criminologist. More precisely, he was the creator of judicial anthropometry: in 1882 he founded the first criminal identification laboratory in France.

Michel Poivert explains: “The iconography of criminal anthropology makes an incursion here at the very moment when the group seeks to define a revolutionary identity.” The surrealists were very interested in the grammar of repression. Dalí, in particular, was passionate about the journal La Nature, a popular science journal which published at least three articles by Bertillon, illustrated with forensic photographs. The photographic fragments used by Dalí are in fact extracted from synoptic tables or tabbed directories by Bertillon. Bertillon’s ambition was to draw up an atlas of human morphology. What modern police was developing is therefore the transformation of the human body into a territory of surveillance and control. Bertillon reduces the body to a set of records.

Michel Poivert underlines that the repetition of the motif of the ear acts in the manner of a «stéréotypie», that is to say of a gesture reproduced in a loop or of a word reiterated without end: the symptom of a mental disorder. What’s closer to ecstasy than a morbid or hysterical fixation? From this point of view, certainly, the judicial photos of ears have their place perfectly in this photomontage, “which precisely mixes devotion and the disciplinary in the pathological figure of ecstasy,” suggests Michel Poivert: Dali’s passion for hysteria inevitably guides us towards Jean-Martin Charcot. Indeed, at the time when Dalí was concerned about a representation of ecstasy, the definition of the phenomenon by theologians was entirely constructed in reaction against the popularization of hysterical ecstasy.

In the text entitled “The Phenomenon of Ecstasy” (published in Le Minotaure, 1933), Dalí himself explains in covert terms the reason for this choice: the ears are “always in ecstasy” he says, probably in allusion to their coiled shape. The ears are shaped like a fractal or vortex. They lead the eye through a whirlwind to their central point, the black orifice of the ear canal… But the photomontage is itself constructed in the manner of an ear, guiding the eye to the portrait of the woman in ecstasy.

The Phenomenon of Ecstasy shows a woman at the heart of the photomontage; she offers the ambiguous spectacle of a being carried away by an emotion of mixed suffering and joy; between the devotional universe of grace and the clinical one of madness. What passion is she devoted to? Terrestrial or celestial?

Dalé expressed it in these terms: “During ecstasy, at the approach of desire, pleasure, anxiety, all opinions, all judgments (moral, aesthetic, etc.) change dramatically. Every image, likewise, changes sensationally. One would believe that through ecstasy we have access to a world as far from reality as that of dreams. The repugnant can be transformed into desirable, affection into cruelty, the ugly into beauty, defects into qualities, qualities into black misery. (The Phenomenon of Ecstasy, 1933).

sources of the text: Libération & open edition journals