Crossed Lines. Matray Ballet

images that haunt us

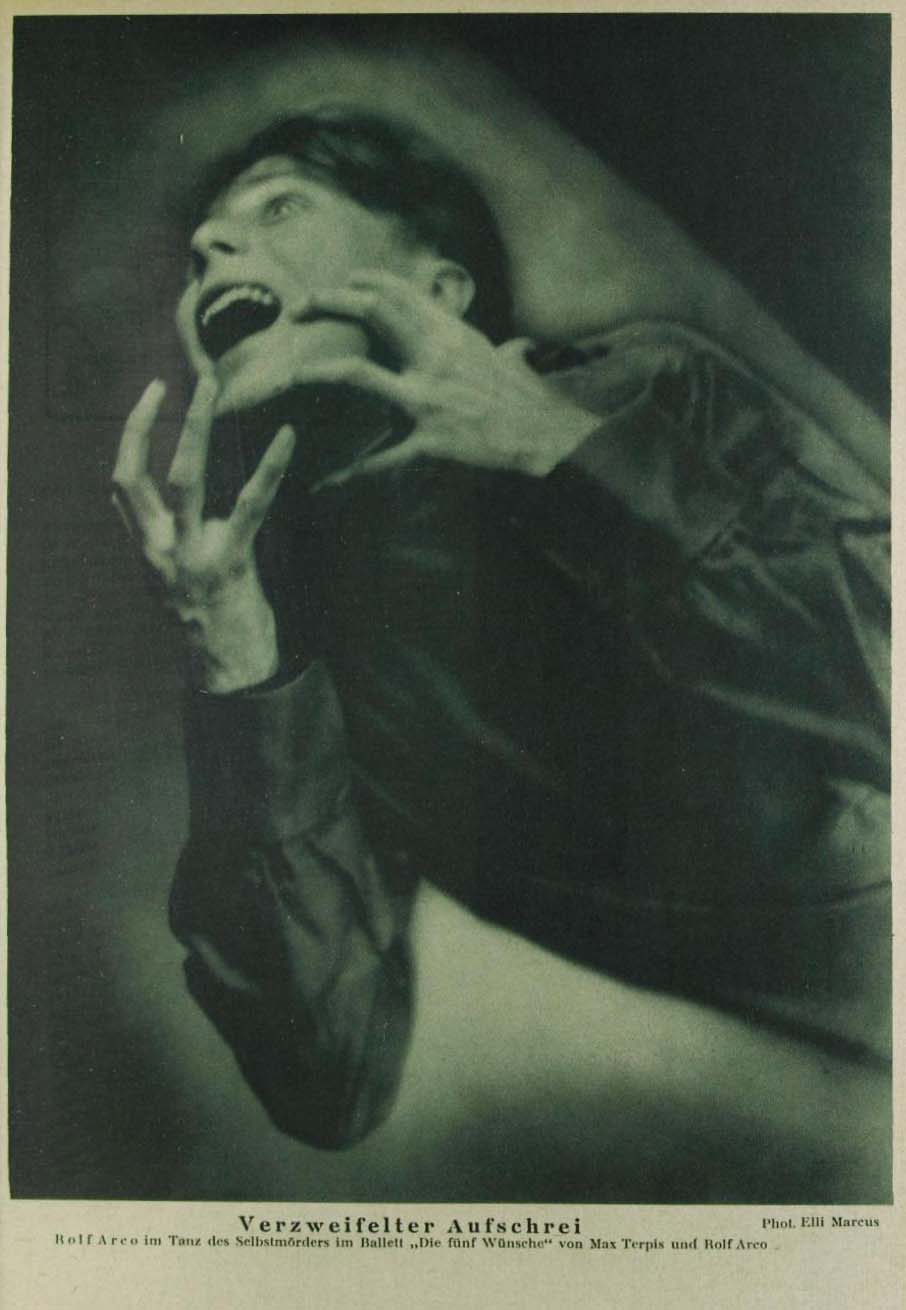

Desperate cry. Rolf Arco in the Dance of the Suicide from the ballet “The Five Wishes” by Max Terpis and Rolf Arco. Stage design. Photographer: Elli Marcus.

Published in Scherl’s magazine in November 1929

![Valda Valkyrien [Adele Frede, Adele Freed] in the American silent adventure fantasy The Hidden Valley (1916) directed by Ernest Warde.](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/motion-picture-news-14moti_4_0038-valkirien-1916-crp.jpg)

![Valda Valkyrien [Adele Frede, Adele Freed] in the American silent adventure fantasy The Hidden Valley (1916) directed by Ernest Warde.](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52472219344_5c1e0cfc36_o.jpg)

![Valda Valkyrien [Adele Frede, Adele Freed] in the American silent adventure fantasy The Hidden Valley (1916) directed by Ernest Warde.](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52471941686_1cd7c3254e_o.jpg)

Dancer Áine Stapleton talks about her film Horrible Creature, a ‘creative investigation’ of the life of Lucia Joyce

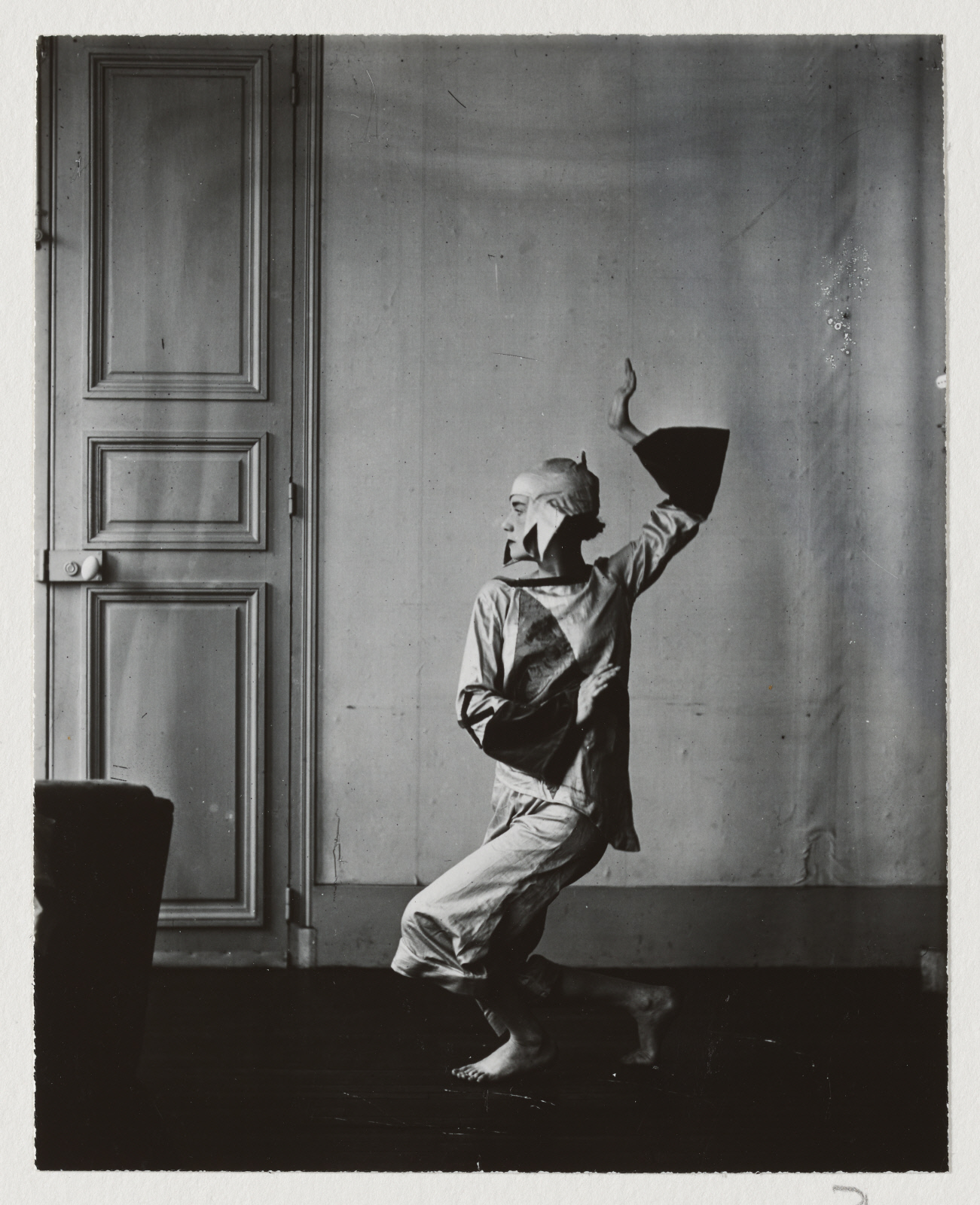

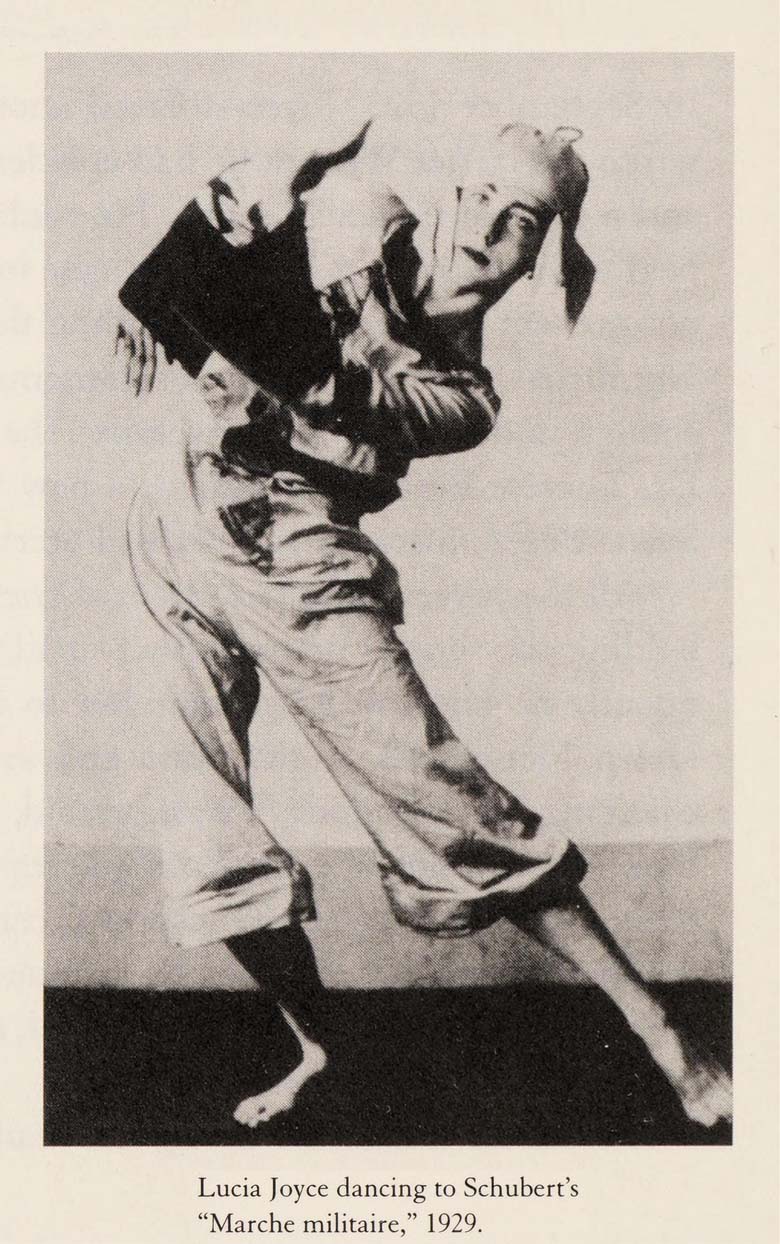

I’ve been creatively investigating the biography of Lucia Joyce (daughter of the writer James Joyce) since 2014, through both choreography and film.

Lucia once commented to a family friend in Paris that she wanted to ‘do something’. She wanted to make a difference and to creatively have an impact on the world around her. Dancing was her way of having an impact. She trained hard for many years and worked with various avant-garde teachers including Raymond Duncan. She created her own costumes, choreographed for opera, entered high profile dance competitions in Paris, and even started her own dance physical training business after apprenticing with modern dance pioneer Margaret Morris.

Until this time she had lived almost entirely under the control of her family, and had to share a bedroom with her parents well into her teens. I imagine that dancing must have been a revolutionary feeling for her, and would have offered her an opportunity to process her chaotic and sometimes toxic upbringing. It was during these dancing years that she was finally allowed to spend some time away from her family, but this freedom did not last long. Her father’s artistic needs and his sexist disregard for her career choice interrupted her training at a vital stage. She was forced to stop dancing, and the circumstances surrounding this time remain unclear. I do not believe that she herself made the decision to quit dancing. Lucia was incarcerated by her brother in 1934, and then remained in asylums for 47 years. She died in 1982 and is buried in Northampton England, close to her last psychiatric hospital.

I’ve read Lucia’s writings repeatedly over the last four years, and my opinion of her hasn’t changed. She was a kind, funny, intelligent, creative and loving person. After her father James’ death in 1941, she had one visit from her brother and no contact from her mother, yet she only writes good things about her family. She was consistently thankful to those people who made contact with her during her many years stuck in psychiatric care. She appreciated small offerings from friends, such as an additional few pounds to buy cigarettes, a radio to keep her company, a new pair of shoes or a winter coat, all of which seemed to offer her some comfort in her later years.

I have no interest in romanticising Lucia’s relationship with her father. I also don’t believe that she was schizophrenic. I think that whatever mental strain Lucia experienced was brought on by those closest to her. Her supposed fits of rage or out of the ordinary behaviour only brought to light her suffering. We know that many women have been mistreated and silenced throughout history. Why do we still play along with a romanticised version of abuse? And why is James and Lucia’s relationship, or ‘erotic bond’ as Samuel Beckett described it, regarded as an almost tragic love story?

Horrible Creature (2020) examines Lucia’s story in her own words, and also focuses on the environment which shaped her during this time. The work attempts to tap into that invisible energy that can provide each of us with a real sense of aliveness and connectedness to the world around us, even in moments of great suffering.

Quoted from Raidió Teilifís Éireann, Ireland’s National Public Service Media

![Tilly Losch [1904-1974] German show dancer from the 1930s. Previously a solo dancer at the State Opera. In 1931 she married American millionaire Edward James. She acts in two films, which, however, do not make her famous. Spaarnestad Photo. Het Leven](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/tilly-losch-1904-1974-duitse-showdanseres-uit-de-dertiger-jaren.-voordien-solodanseres-bij-de-staatopera.-in-1931-trouwt-zij-met-de-amerikaanse-miljonair-edward-james.-zij-acteert-in-ee.jpeg)

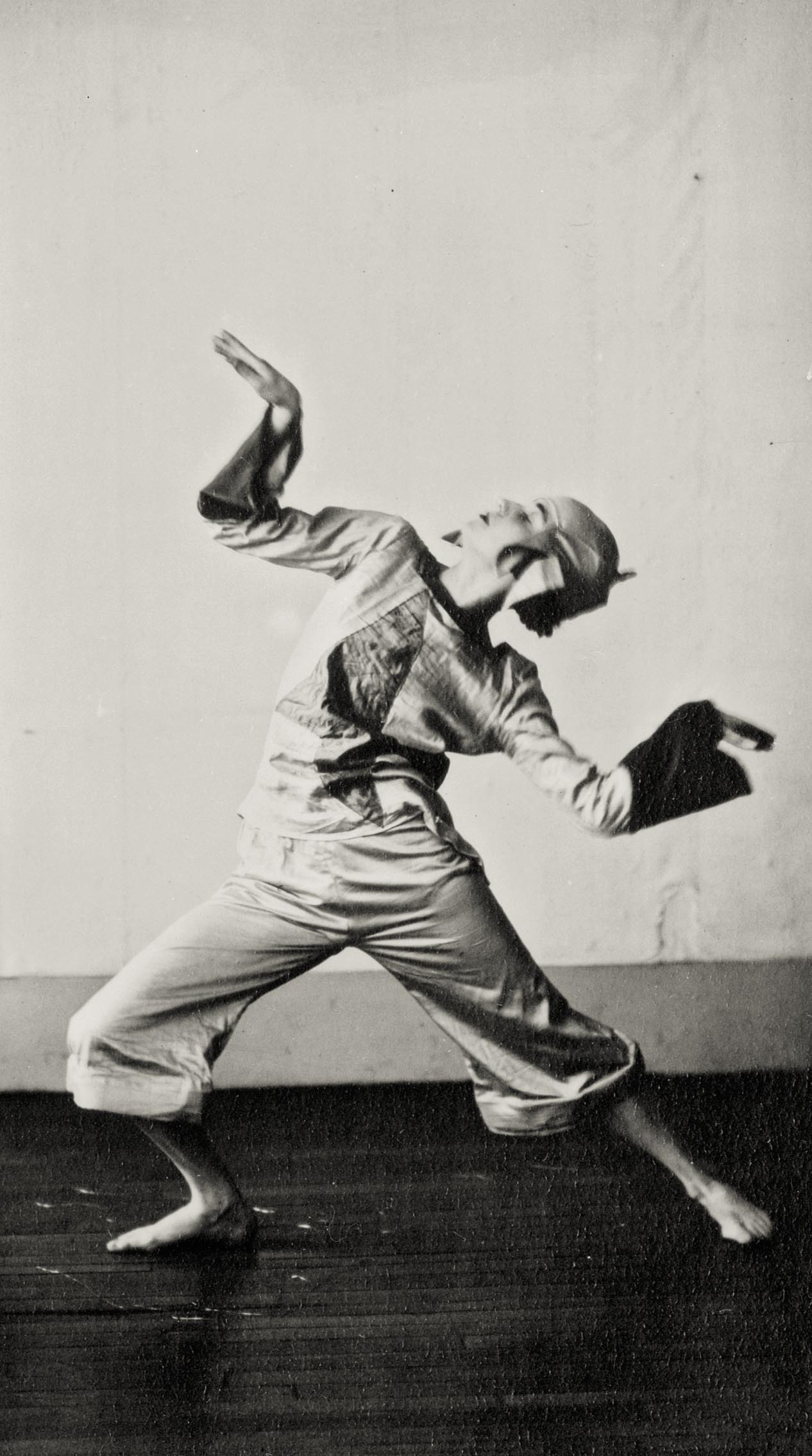

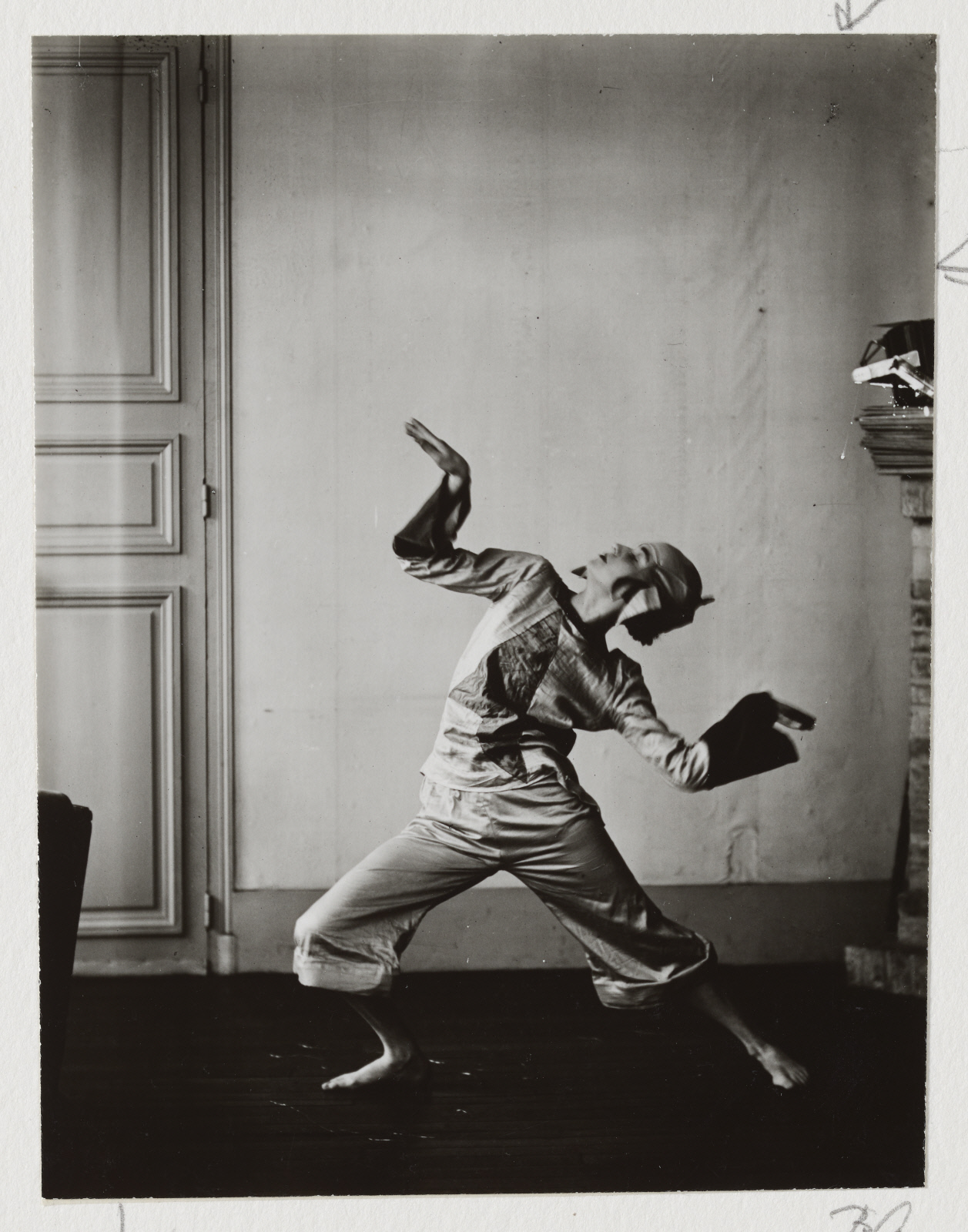

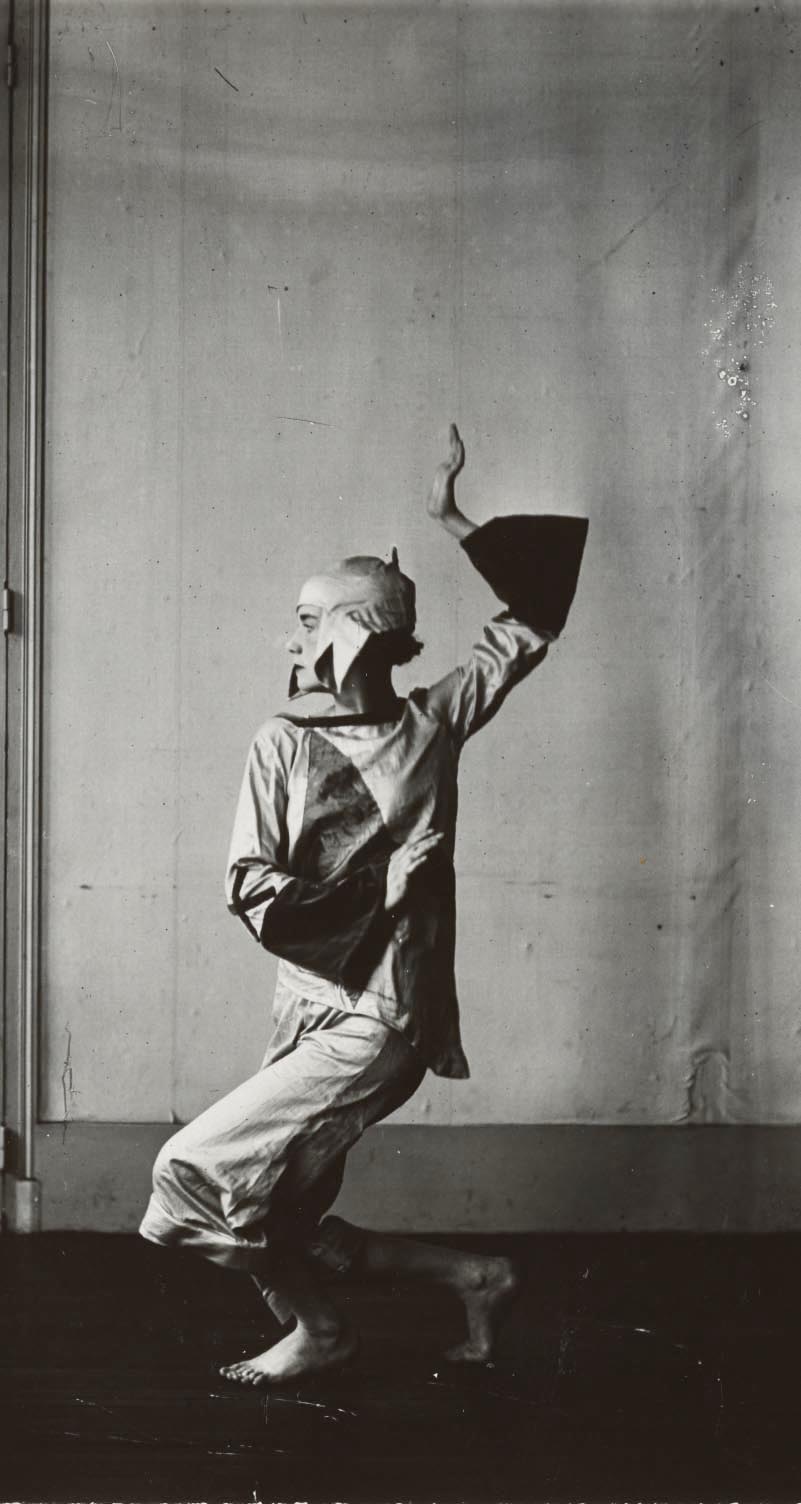

While the identity of the male Pierrot figure remains a mystery, the woman pictured in the present work is likely dancer and actress Erwina Kupferova, the artist’s muse and first wife.