Uncredited photographer on source. Blindstamp on right lower corner of the image reads: G.L. Arlaud.

images that haunt us

According to the seller, Gabriele Bacchiega (eBay profile photo-stereo) all these Autochromes are somehow related to the writer and socialite Ernesta Stern (born Maria Ernesta Hierschel de Minerbi, pen-name Maria Star) (1854 – 1926) or the Salon she held in Paris at 68 rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré. Read more about her here

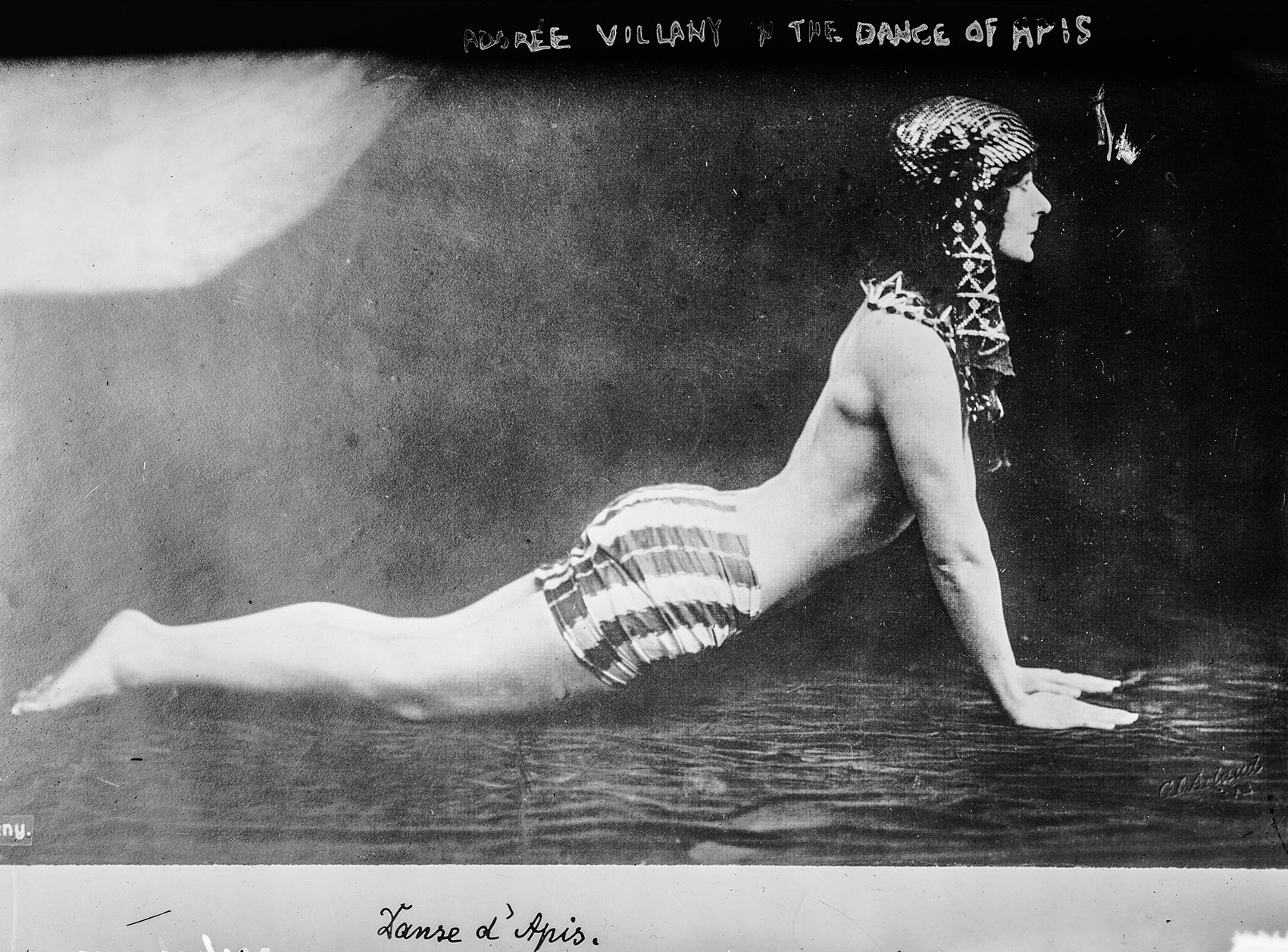

Paris, 1909. Serge Diaghilev engage Ida Rubinstein dans les Ballets russes pour le rôle-titre de Cléopâtre, à l’opéra

Garnier. Cette interprétation est remarquée, ainsi que le nez de la diva.

Les costumes sont signés Léon Bakst et le final inspire le Souvenir de la saison d’Opéra Russe 1909 du peintre Kees van Dongen. Nijinski danse sa première saison des Ballets russes, dans le rôle d’un esclave peu vêtu, éblouissant le public parisien.

From : Otto Portraits : Daguerre & Drouot

Paris, 1909. Serge Diaghilev engages Ida Rubinstein in the Ballets Russes for the title role of Cleopatra, at the opera

Garnier. This interpretation is noticed, as well as the nose of the diva.

The costumes are by Léon Bakst and the finale inspires the Souvenir de la saison d’Opéra Russe 1909 by the painter Kees van Dongen. Nijinsky danced his first season of the Ballets Russes, in the role of a scantily dressed slave, dazzling the Parisian audiences.

Portrait dynamique : Ida Rubinstein dans un costume pour Cléopâtre, ballet en un acte, argument d’après Pouchkine.

Remarquables décors et costumes de Léon Bakst, pour la première au théâtre du Châtelet.

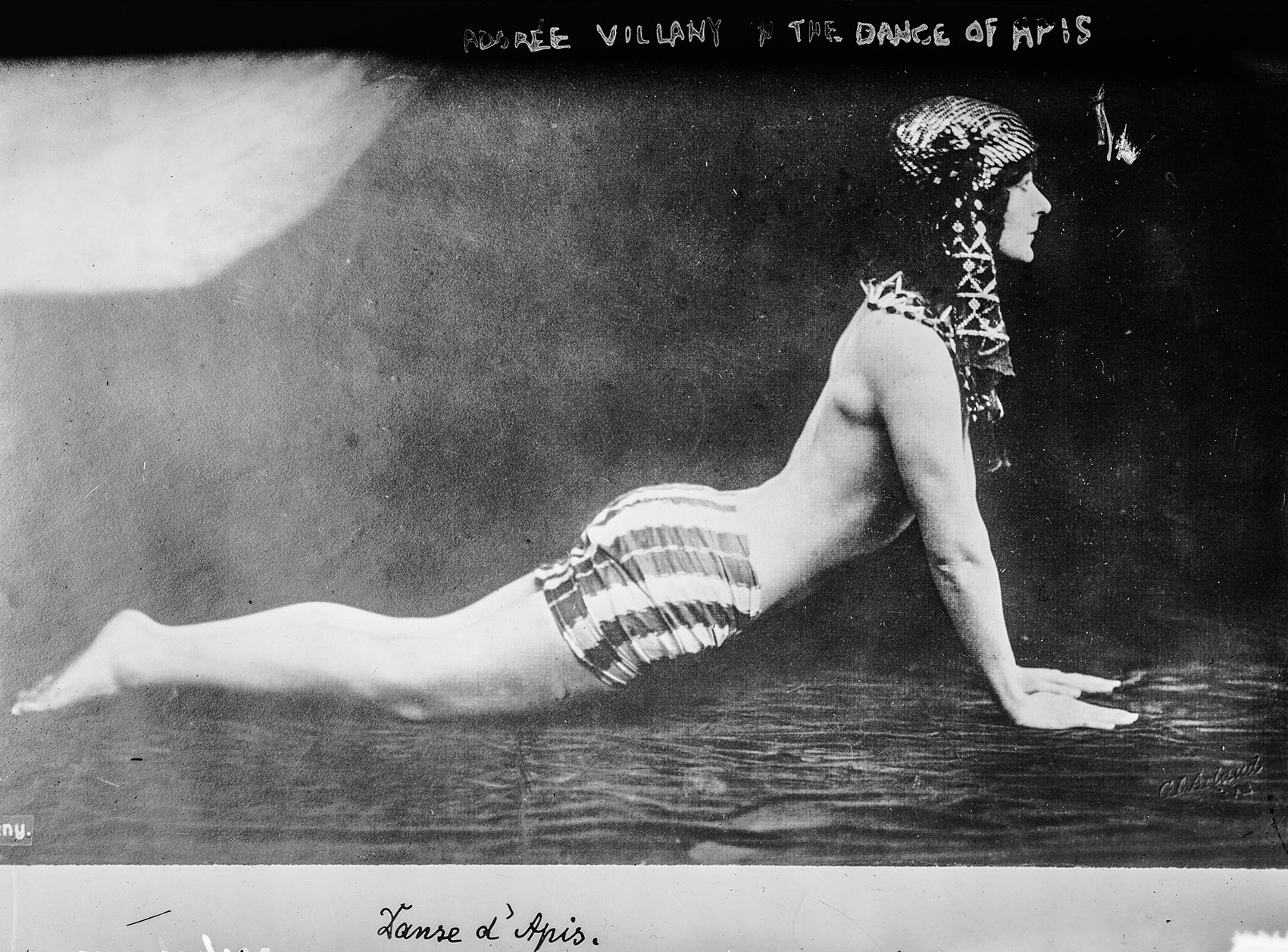

“Le 13 juin 1913 est créée au théâtre du Châtelet à Paris une œuvre rutilante et hybride : la Pisanelle ou la Mort parfumée, texte français du dramaturge italien Gabriele d’Annunzio. La participation russe est prépondérante : Lev Bakst pour le décor, Ida Rubinstein dans le rôle principal, Vsevolod Meyerhold pour la mise en scène.

La richissime actrice est la commanditaire du spectacle dont la chaude volupté répond à ses vœux. Dans cette œuvre, D’Annunzio a voulu faire se mesurer latinité et orientalisme.

Les circonstances qui ont procédé à la création de la pièce dans l’atmosphère survoltée d’une vie artistique dominée par les Ballets russes…”

Gérard Abensour, Monde Russe, 2007. From : Otto Portraits : Daguerre & Drouot

“On June 13, 1913, a gleaming and hybrid work was created at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris: La Pisanelle ou la Mort parfumée, a French text by the Italian playwright Gabriele d’Annunzio. The Russian participation is preponderant: Lev Bakst for the decor, Ida Rubinstein in the main role, Vsevolod Meyerhold for the staging.

The wealthy actress is the sponsor of the show marked by her fervent voluptuousness. In his work, D’Annunzio wanted to present Latinism and Orientalism into balance.

The circumstances that led to the creation of the piece in the charged atmosphere of an artistic life dominated by the Ballets Russes…”

Gérard Abensour, Monde Russe, 2007.

All the the photographs and texts in this post had been retrieved from the catalogue of this auction :

Otto Portraits. Un fonds d’atelier photographique est retrouvé intact après cent ans d’oubli. Le studio du portraitiste Otto, place de la Madeleine, accueillait le Tout-Paris de la Belle Époque. Otto et ses fils y menaient grand train.

Vente aux enchères ‘Photographies par Otto Wegener (1849-1924)’ à Hôtel de vente Drouot le 8 novembre 2018 – Daguerre & Drouot

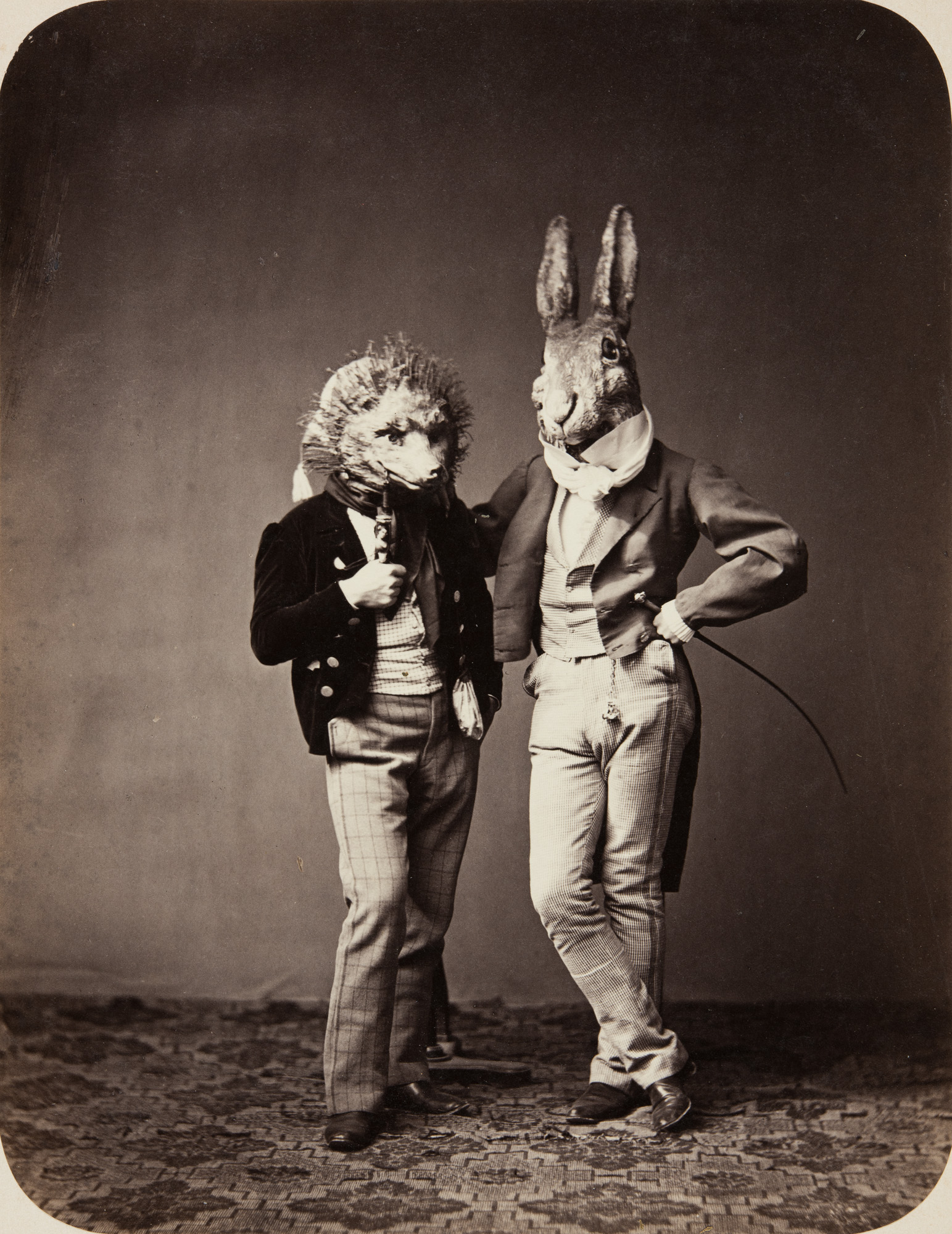

Von Künstlervereinigungen ausgerichtete Maskenfeste waren im 19. Jahrhundert in München überaus populär. Zu den frühen Aufnahmen dieser speziellen Festkultur zählen die fast surreal anmutenden, rund 30 Gruppen- und Einzelporträts, die der Fotograf Joseph Albert (1825–1886) von den Teilnehmenden am Maskenfest “Die Märchen” schuf. Das von der Vereinigung “Jung-München” veranstaltete Fest fand in der Faschingszeit am 15. Februar 1862 statt, geladen wurde in das königliche Odeon, zahlreiche Mitglieder der bayerischen Königsfamilie nahmen daran teil, darunter auch der spätere “Märchenkönig” Ludwig II.

Die Kostüme entsprachen der Vorliebe der Zeit für das mittelalterliche und märchenhafte Genre, das sich auch in der Kunst der Epoche widerspiegelte. Zu den dargestellten Märchen gehörten “Kindermärchen” wie “Hänsel und Gretel”, “Waldmärchen” wie “Rotkäppchen” oder auch “Thiermärchen” wie der “Gestiefelte Kater” oder “Hase und Igel”. Für den Fotografen Albert präsentierten sich die Kostümierten abseits des Geschehens entweder allein in typisch nachempfundener Pose oder zu mehreren für ausgewählte Szenen in der Tradition “lebender Bilder”, den sogenannten “tableaux vivants”. [quoted from : Münchner Stadtmuseum ~ Sammlung Dietmar Siegert]

Mask festivals organized by artists’ associations were extremely popular in Munich in the 19th century. The early photographs of this festival culture include these almost surreal-looking images: around thirty group and individual portraits that the photographer Joseph Albert (1825-1886) created of the participants in the masked festival “The Fairy Tales”, the festival, organized by the “Jung-München” association, took place during the carnival period on February 15, 1862. Among the invited guests were numerous members of the Bavarian royal family, including the later “fairy tale king” Ludwig II.

The costumes corresponded to the period’s penchant for the medieval and fairytale genre, which was also reflected in the art of the period. The fairy tales presented included “children’s fairy tales” such as “Hansel and Gretel”, “forest fairy tales” such as “Little Red Riding Hood” or “animal fairy tales” such as “Puss in Boots” or “Hase and Hedgehog”. The costumed people presented themselves, for the photographer, away from the action either alone in a typically imitated pose or in groups for selected scenes in the tradition of “living pictures”, the so-called “tableaux vivants”.

Münchner Stadtmuseum ~ Sammlung Dietmar Siegert

Marie Haushofer presented roles that women had played in different eras and centuries. At the same time, she also traced the path of women in their cultural-historical development – from servitude and lack of culture, interrupted by a brief flash of female domination in the kingdom of the Amazons […] Read more below

Evas Töchter. Münchner Schriftstellerinnen und die moderne Frauenbewegung 1894-1933

Eve’s daughters. Munich women writers and the modern women’s movement 1894-1933

Around 1900 profound changes took place in all areas of life. There is a new beginning everywhere, in the circles of art, literature, music and architecture. The naturalists are the first to search for new possibilities of representation. They are followed by other groups and currents: impressionism, art nouveau, neo-classical, neo-romantic and symbolism. Even if this epoch does not form a unit, one guiding principle runs through all styles: the awareness of a profound turning point in time.

It is generally known that before the turn of the century Munich became one of the most important cultural and artistic sites in Europe. What is less well known is that Munich has also become a center of the bourgeois women’s movement in Bavaria since the end of the 19th century. At this time, a lively scene of the women’s movement formed in the residence city, which subsequently gained great influence on the bourgeoisie throughout Bavaria.

Since 1894, Munich has been shaped by the modern women’s movement, which advocates the right to education and employment for women. At that time, the city was decisively shaped by women such as Anita Augspurg, Sophia Goudstikker, Ika Freudenberg, Emma Merk, Marie and Martha Haushofer, Carry Brachvogel, Helene Böhlau, Gabriele Reuter, Helene Raff, Emmy von Egidy, Maria Janitschek and many other women’s rights activists and writers and artists, all of whom are members of the Association for Women’s Interests, which is largely responsible for the spread of the modern women’s movement in Bavaria. At that time, they all set out in search of a new self-image for women, questioned the traditional role models in the bourgeoisie and attempted to redefine gender roles.

In this context, on October 1899 the First Bavarian Women’s day was celebrated. The crowning glory of the First General Bavarian Women’s Day in 1899 was a festive evening that took place on October 21, 1899 in the large hall of the then well-known Catholic Casino at Barer Straße 7.

The first part of the festive evening was the performance of an impressive festival play: Cultural images from women’s lives. Twelve group representations [„Zwölf Culturbilder aus dem Leben der Frau“]. The piece was written by the painter a poet Marie Haushofer (1871-1940) especially for this occasion. Sophia Goudstikker directed it and she also played a part. The majority of the roles were played by many other protagonists of the Munich women’s movement. A few days later, Sophia Goudstikker photographed the twelve group portraits in the Elvira photo studio (Atelier Elvira). She glued the photographs into a leather album entitled Marie Haushofer’s festival for the first general Bavarian women’s day in Munich. October 18-21, 1899 [Marie Haushofers Festspiel zum Ersten allgemeinen Bayrischen Frauentag in München, 18. – 21. Oktober 1899]. Those are the 13 surviving scene photos (group portraits) that documented the event; today they are part of the Munich City Archive (Stadtarchiv München).

In her festival play, Marie Haushofer presented roles that women had played in different eras and centuries. At the same time, she also traced the path of women in their cultural-historical development – from servitude and lack of culture, interrupted by a brief flash of female domination in the kingdom of the Amazons, to burgeoning knowledge, to work, freedom and finally the union of women who from then on did their work – but also have to assert powerfully achieved new social status through unity. The present represents the last group in which “modern women” appear in “modern professions”: telephone operators, bookkeepers, scholars, painters, etc. They are accompanied by the allegorical figures of Faith, Love, Hope (*) and the Spirit of Work (**) that liberates all women / working women. Finally, the female audience is called upon to work and to actively shape together the present role of women.

[(*) see photo on bottom of this post (last photo) / (**) last-but-one photo]

Further productions took place in Nuremberg in 1900 and on November 28 and 30, 1902 at the Bayreuth Opera.

But the festive evening of Bavarian Women’s Day did not end with the performance of the festival play. In the second part of the evening, “poems of modern women poets” were presented. There were works by Ada Negri, Lou Andreas-Salomé, Alberta von Puttkammer, Anna Ritter, Ricarda Huch and Maria Janitschek. The short prose text Nordic Birch by the Art Nouveau artist and writer Emmy von Egidy was also read.

[adapted text quoted (an translated) from : Evas Töchter : Frauenmut und Frauengeist : Literatur Portal Bayern]

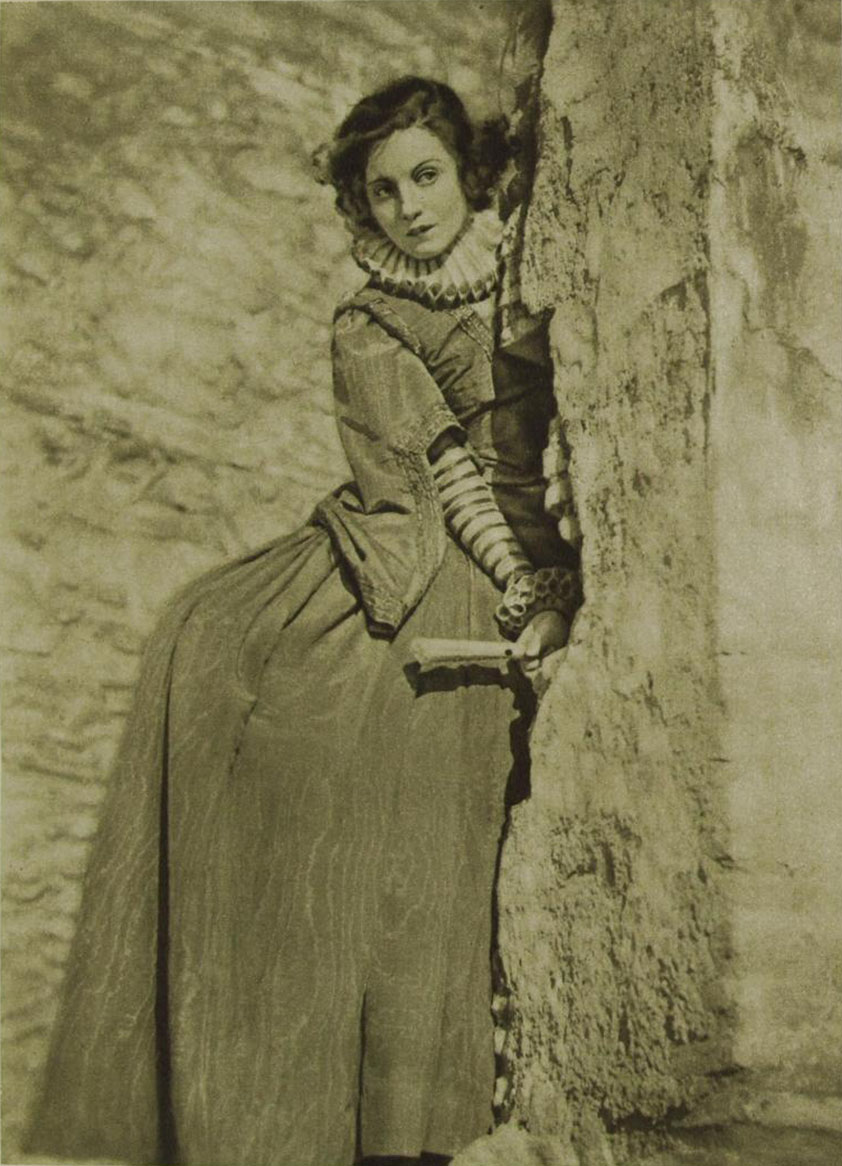

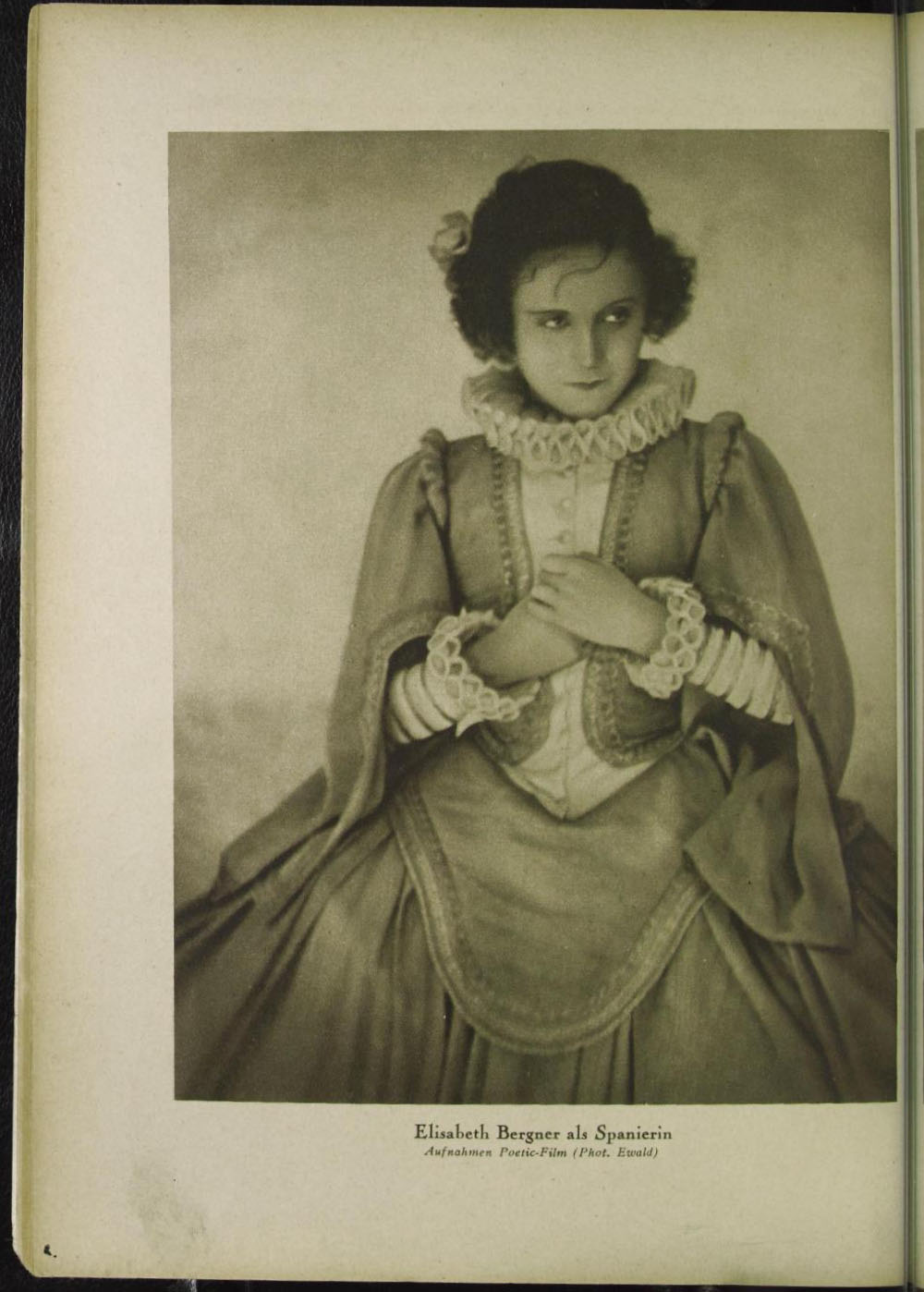

![Juana im Kampf mit ihrem Spiegelbild im Teich [Doña Juana, 1928] UHU 4.1927-28, H.3 Elisabeth Bergner in Dona Juana, 1928](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/uhu-4.1927-28-h.3-elisabeth-bergner-in-dona-juana-crp.jpg)

![Juana im Kampf mit ihrem Spiegelbild im Teich [Doña Juana, 1928] UHU 4.1927-28, H.3 Elisabeth Bergner in Dona Juana, 1928](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52794499433_c705132906_o.jpg)

All images from UHU Magazin: Mit Elisabeth Bergner in Spanien by Paul Czinner, a detailed review of Béla Balázs film Doña Juana, starring Elisabeth Bergner. Aufnahmen: Poetic-Film (phot. Ewald)