Frida Kahlo · Alvarez Bravo

images that haunt us

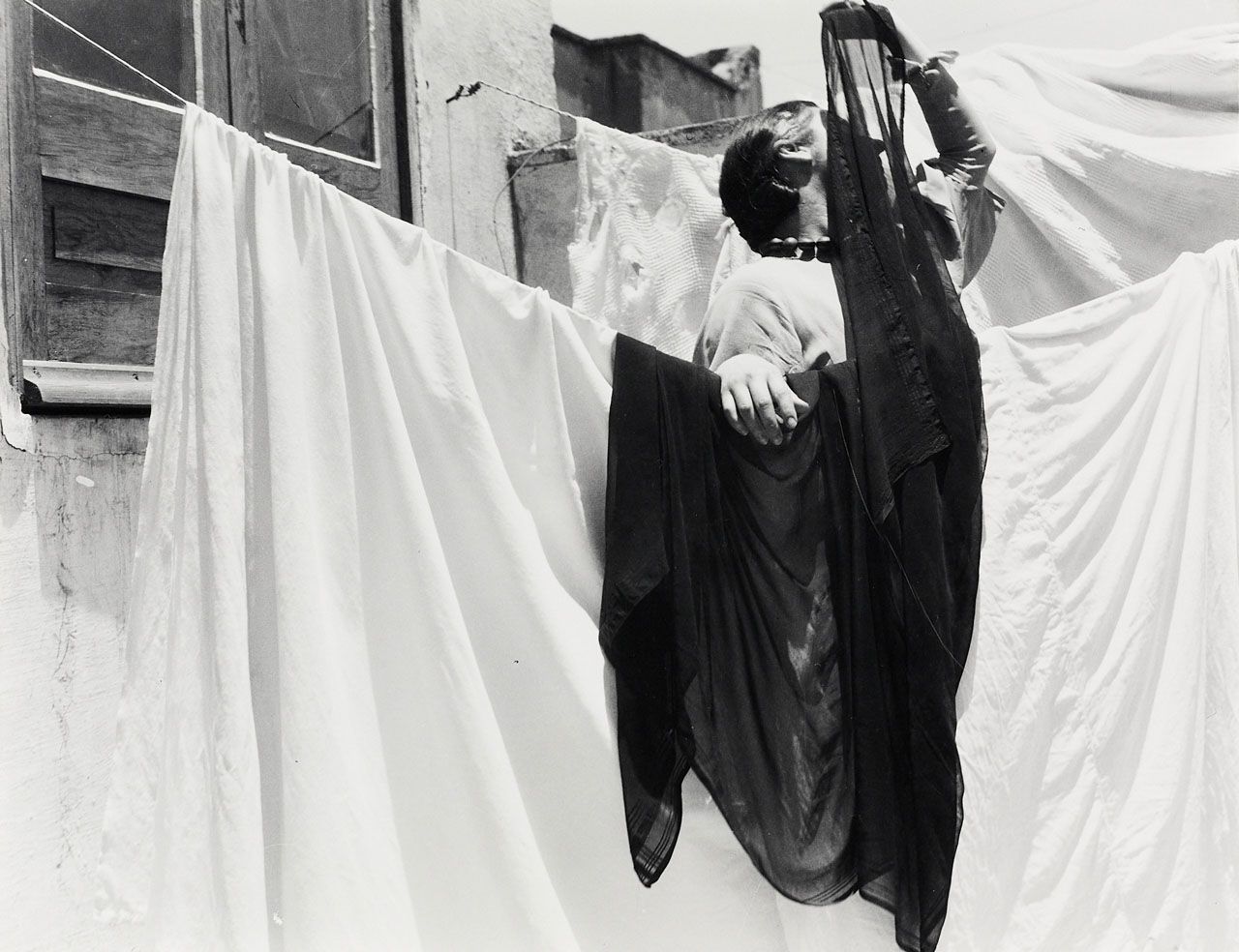

In El eclipse (1933), Álvarez Bravo achieved a dynamic geometry of crisscrossing diagonals. Standing on a shallow corner of a rooftop, a woman is partially concealed by sheets bleaching in the sun and by her dark rebozo, which she presumably holds in front of her face to look at an eclipse. His carefully composed images reveal his modern sense of aesthetics. | text Blanton Museum of Art Collections

mulating the pose of a Flamenco dancer, this woman dramatically turns her head sideways and upwards, while extending one arm high up in the air. Holding a black, sheer cloth over her face and shielding her eyes from the strong Mexican sun, she enacts Manuel Alvarez Bravo’s conception of an eclipse.

At the same time, light bounces off the hanging white sheets, saturating the off-center areas of the photograph.

Alvarez Bravo made many images of linens and clotheslines, exploring the interplay between draped fabric and angular architecture. Here, the addition of a figure, seemingly engaged in a performance, adds mystery and animation to an otherwise formal study. | text: Getty museum

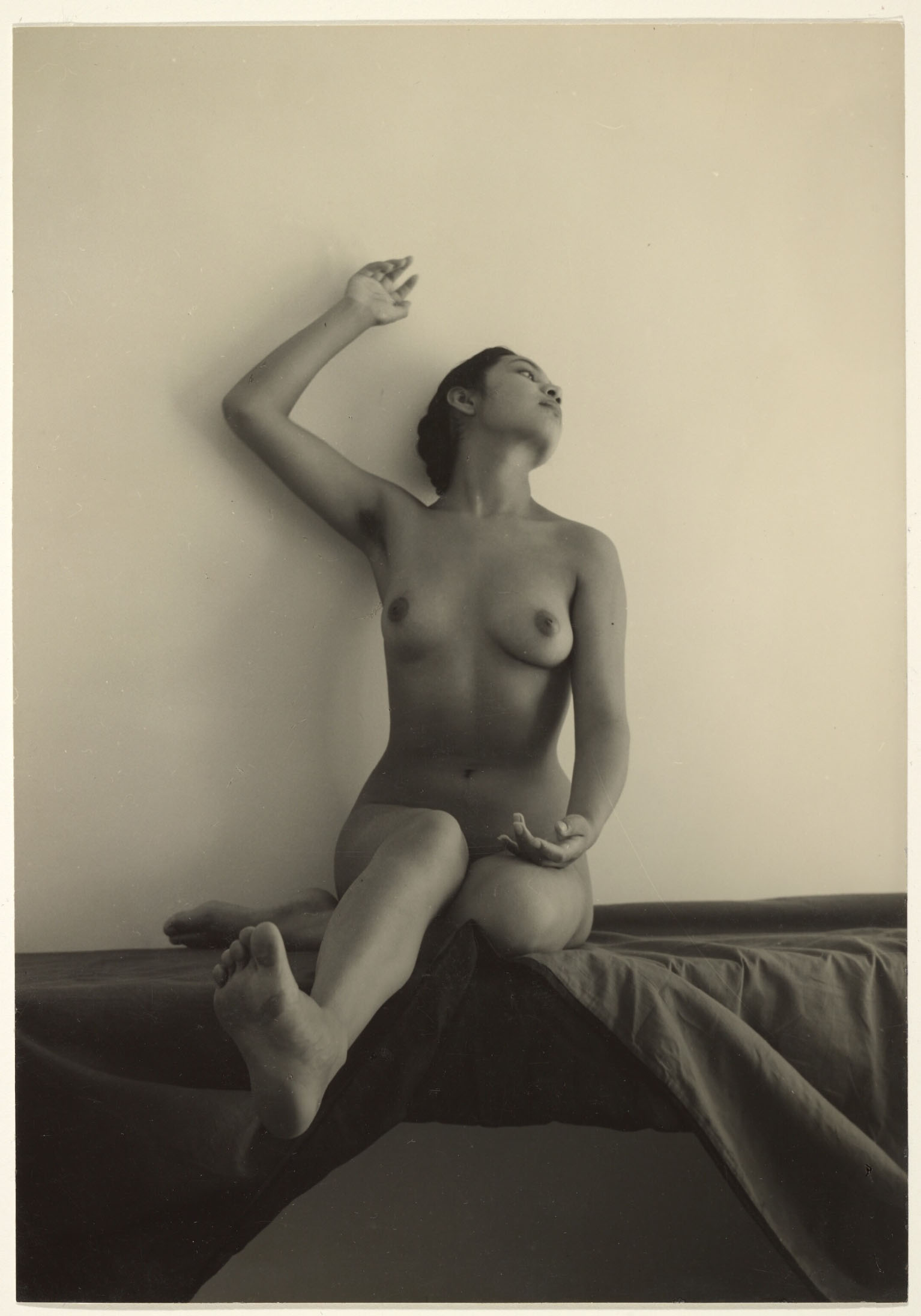

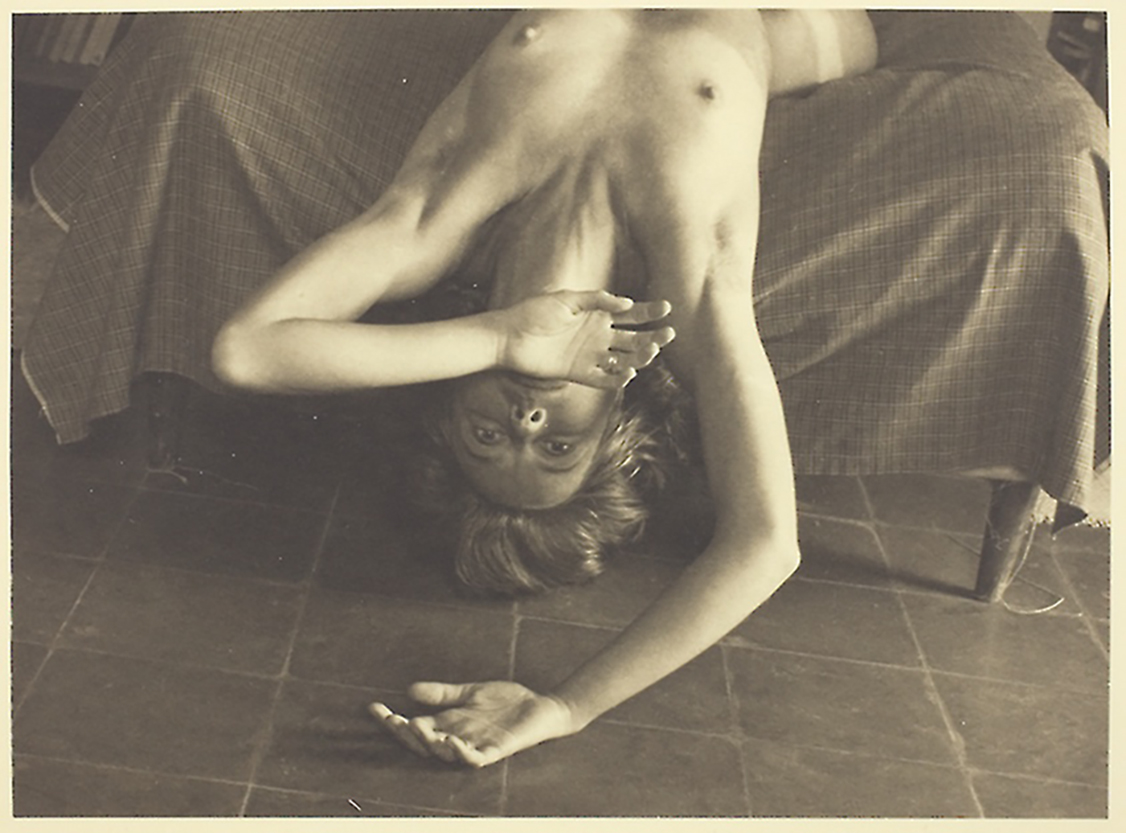

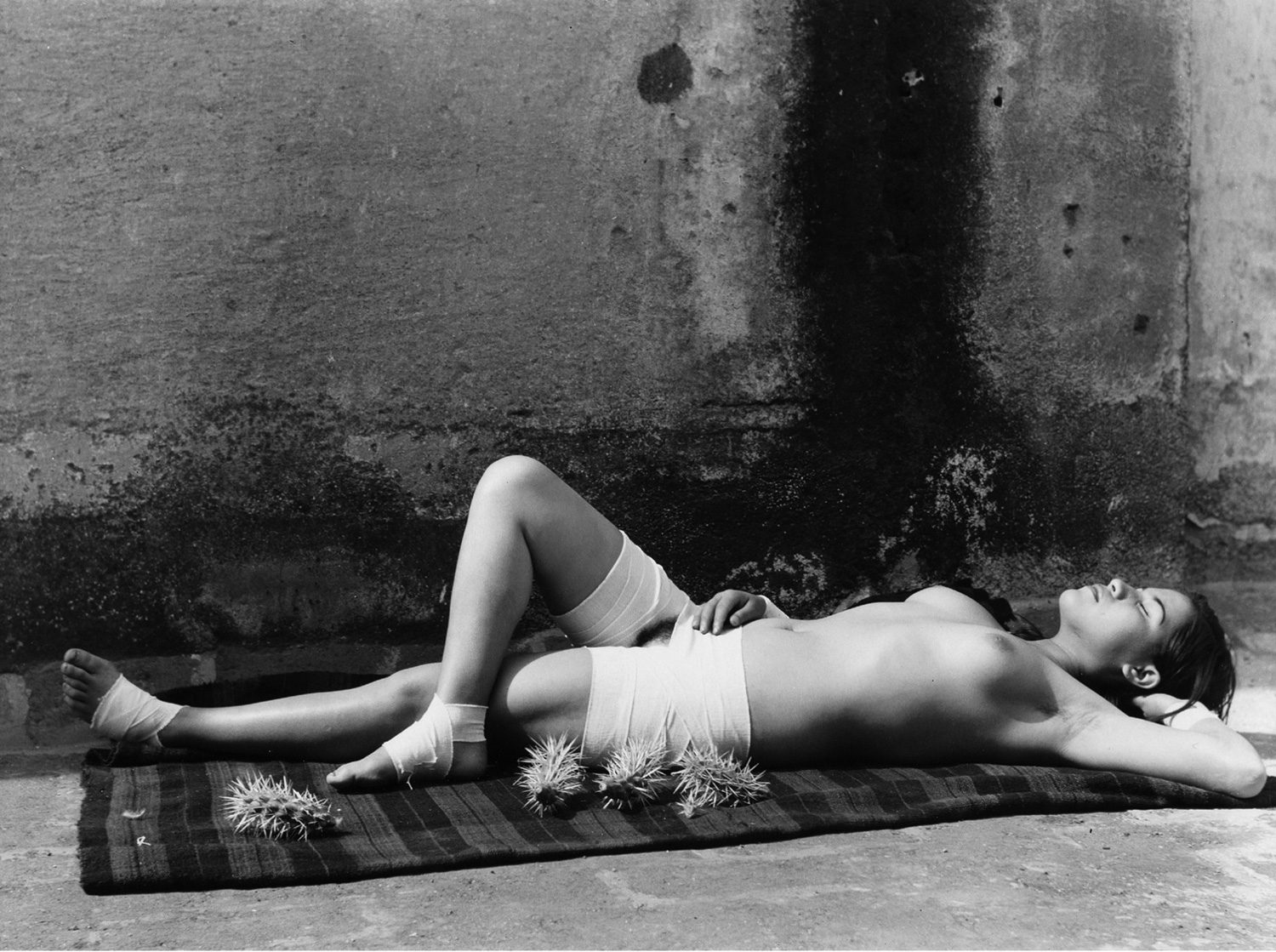

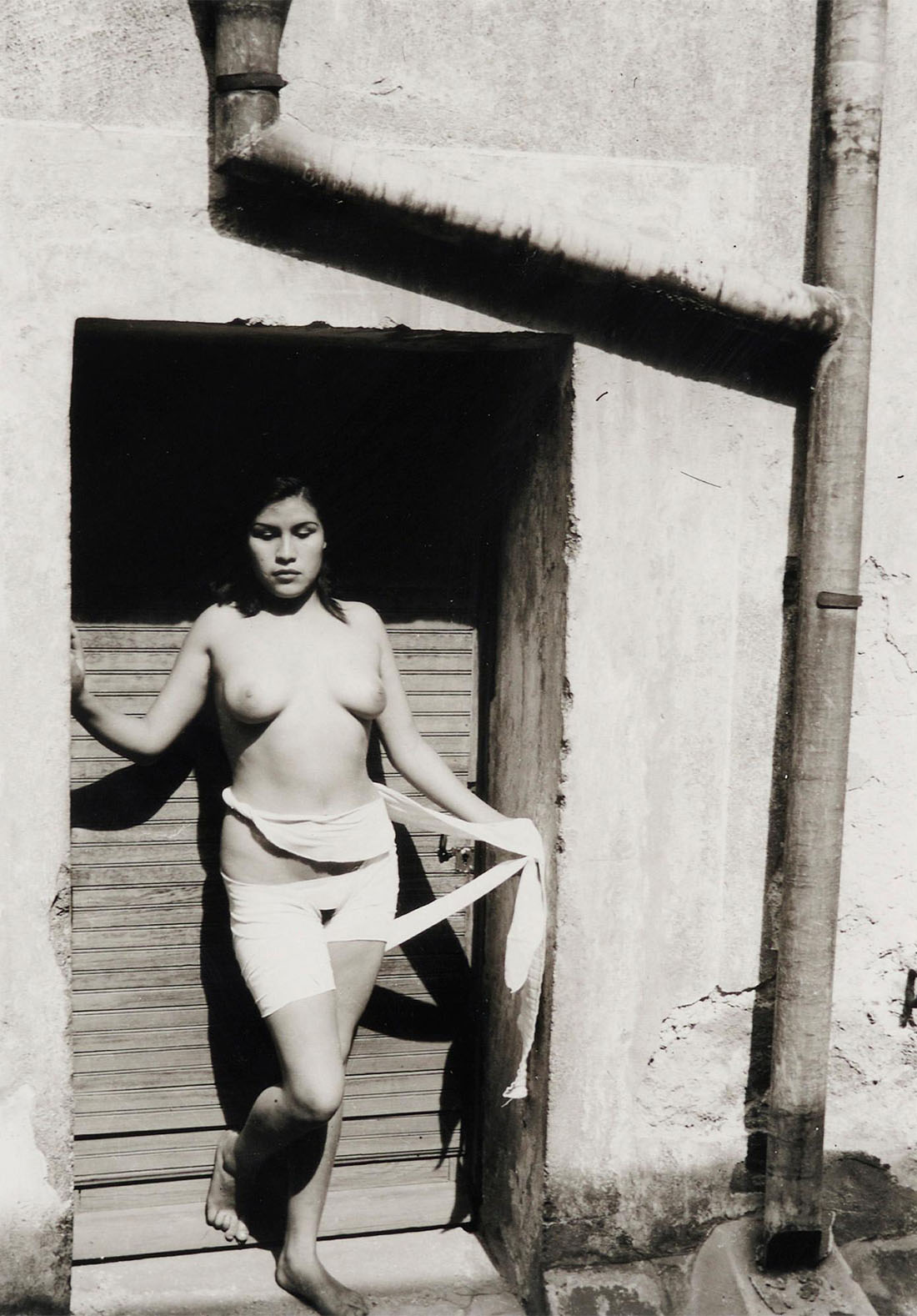

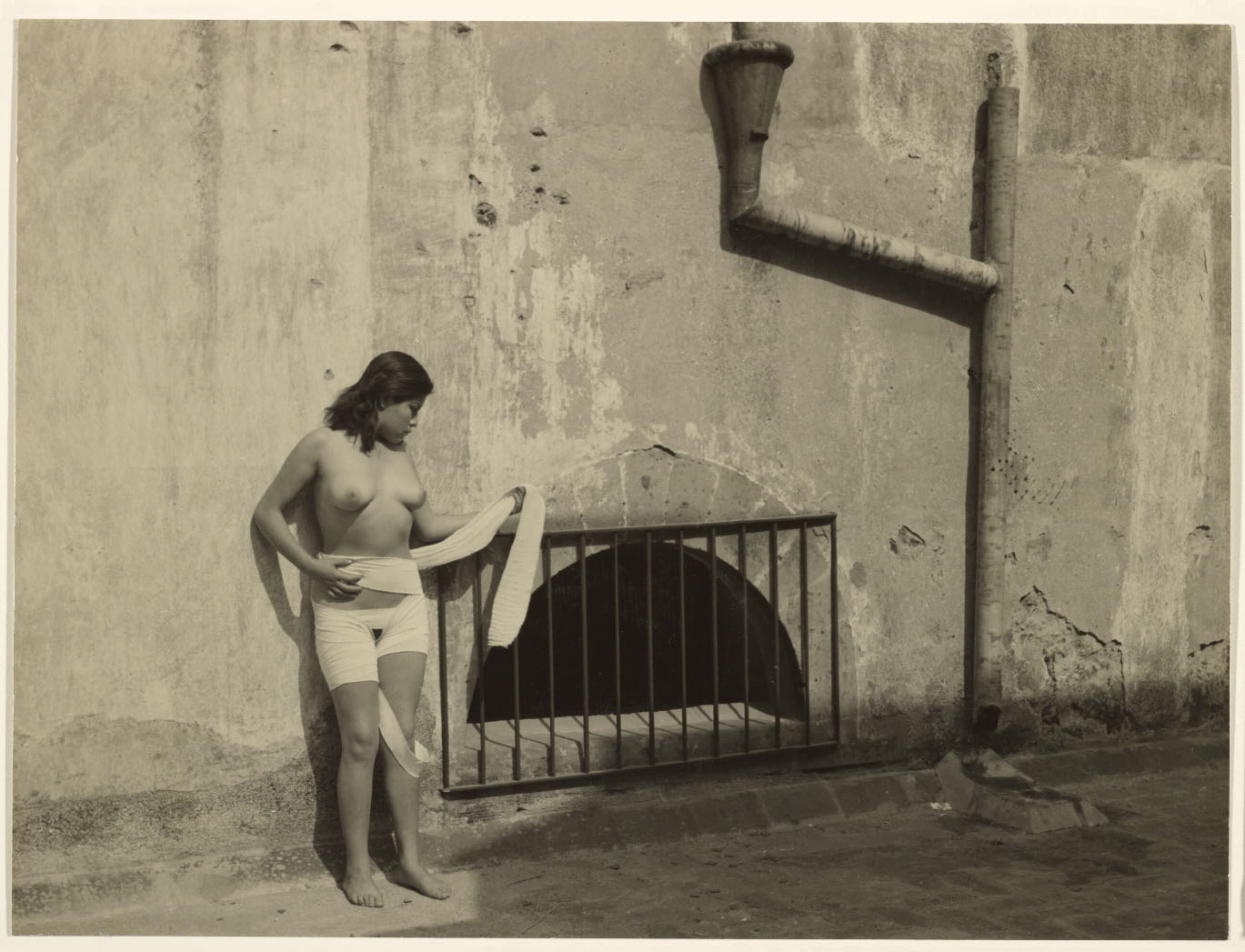

Alvarez Bravo hired a young female model to pose for him while he was teaching photography at the Academia de San Carlos (Academy of San Carlos) in Mexico City in 1937. Over the course of the next few years he created a series of figure studies that are noteworthy for their simple yet powerful compositions. In this picture Alvarez Bravo positioned the young woman on a fabric covered table against a plain white wall. He achieved a balance between divergent elements–stasis and dynamism, tension and relaxation, and positive and negative space.

Manuel Alvarez Bravo directed this model to pose with her head dramatically turned upward. The young woman’s unnatural posture encouraged the presumably male viewer to gaze freely at her eroticized form; her averted face denied her the opportunity to return and confirm the gaze. This pose belongs to an academic tradition of representing women as objects of desire.

Alvarez Bravo produced a series of nude photographs depicting this model. He called the series Morning Notebook, suggesting that the female body was a construction that could be documented and then read like words on a page. During this period, many Surrealist artists, whose work influenced Alvarez Bravo, used the female form in much the same way–for clearly visible consumption. (text quoted from Getty Museum)

(*) Secondary inscription on verso: “Cuaderno de la Mañana (Dicha Puerta)” and “# 8”

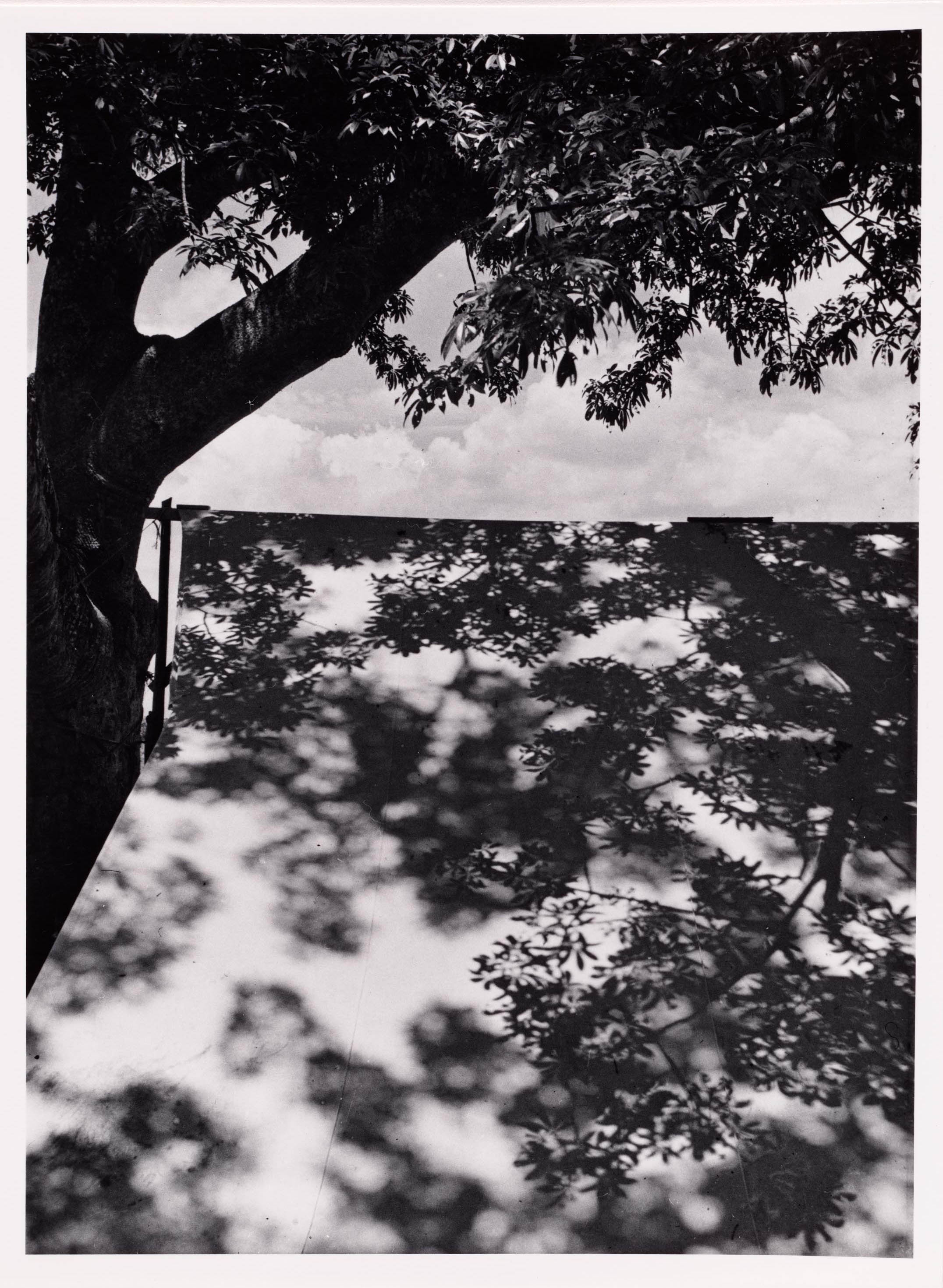

Billowing, black smoke fills the sky, obscuring the grazing burro on the right, in this photograph of an adobe brick kiln. Manuel Alvarez Bravo called this image La Quema, a term meaning “the fire” or “the burning.” Depicting a landscape threatened by human industry, the image may symbolize more sinister historical events. Alvarez Bravo, who came of age during the violent Revolution of 1910-1920, often saw dead bodies burning in the street.

The Mexican people may have viewed the kiln–a site of fiery transmutations–as an allusion to the Spaniards’ conquest and purging of the Aztecs in the 1500s. About this image, one historian has said: “The photograph does not project sorrow or excessive drama, but quiet and noble resignation. Even the human figure standing at the base of the kiln/pyramid has an attitude, extremely Mexican in character, of resigned acceptance of destiny.” | src getty.edu