Advances in Japanese cinema, as much as any other nation, are about breaks from conventional styles and means of representation. Every generation has turned out a handful of directors whose work has broken the mould to go far beyond the standards set by their contemporaries. One of the first of these was Teinosuke Kinugasa, who all the way back in the 1920s was busily familiarising himself with developments in European cinema, Soviet theories of associative montage and movements in the artistic avant-garde such as expressionism, impressionism and surrealism, and in collaboration with a handful of young experimental writers of the day, known as the Shinkankaku school, or Neo-Perceptionists (sometimes referred to as the Neo-Sensationalists), became the first director in Japan to realise his ambition of treating cinema as a distinct art form in its own right, divorced from the commercial concerns of the new mass-audience medium. Quoted from Midnight Eye, visions of Japanese cinema

Based on a treatment by the later 1968 Nobel Prize winning novelist Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972), Kinugasa’s self-financed landmark production Kurutta Ippeiji, hereafter referred to as A Page of Madness (though some sources refer to it by the titles A Crazy Page or A Page Out of Order, and Aaron Gerow’s groundbreaking book on the film argues that the Japanese title should in fact be read as Kurutta Ichipeiji) seems a far cry from the bog-standard theatrically derived Kabuki adaptations and jidai-geki period swashbucklers being produced at the time en masse. The story of a retired sailor who has taken a job as a janitor in a lunatic asylum to look after his insane wife, locked away after attempting to drown their child, a synopsis of the plot can’t begin to explain the power of the film, nor the audacity of its vision.

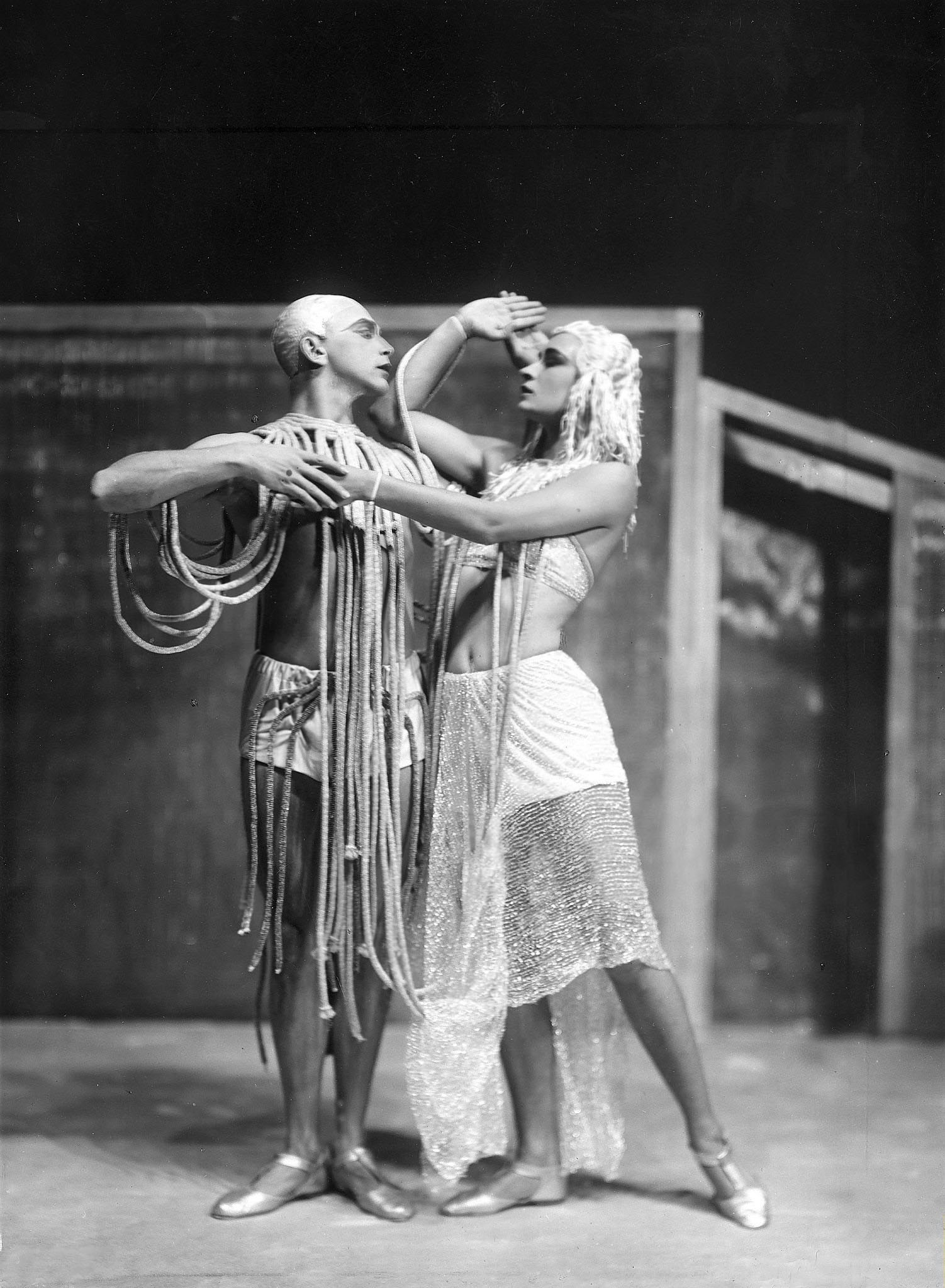

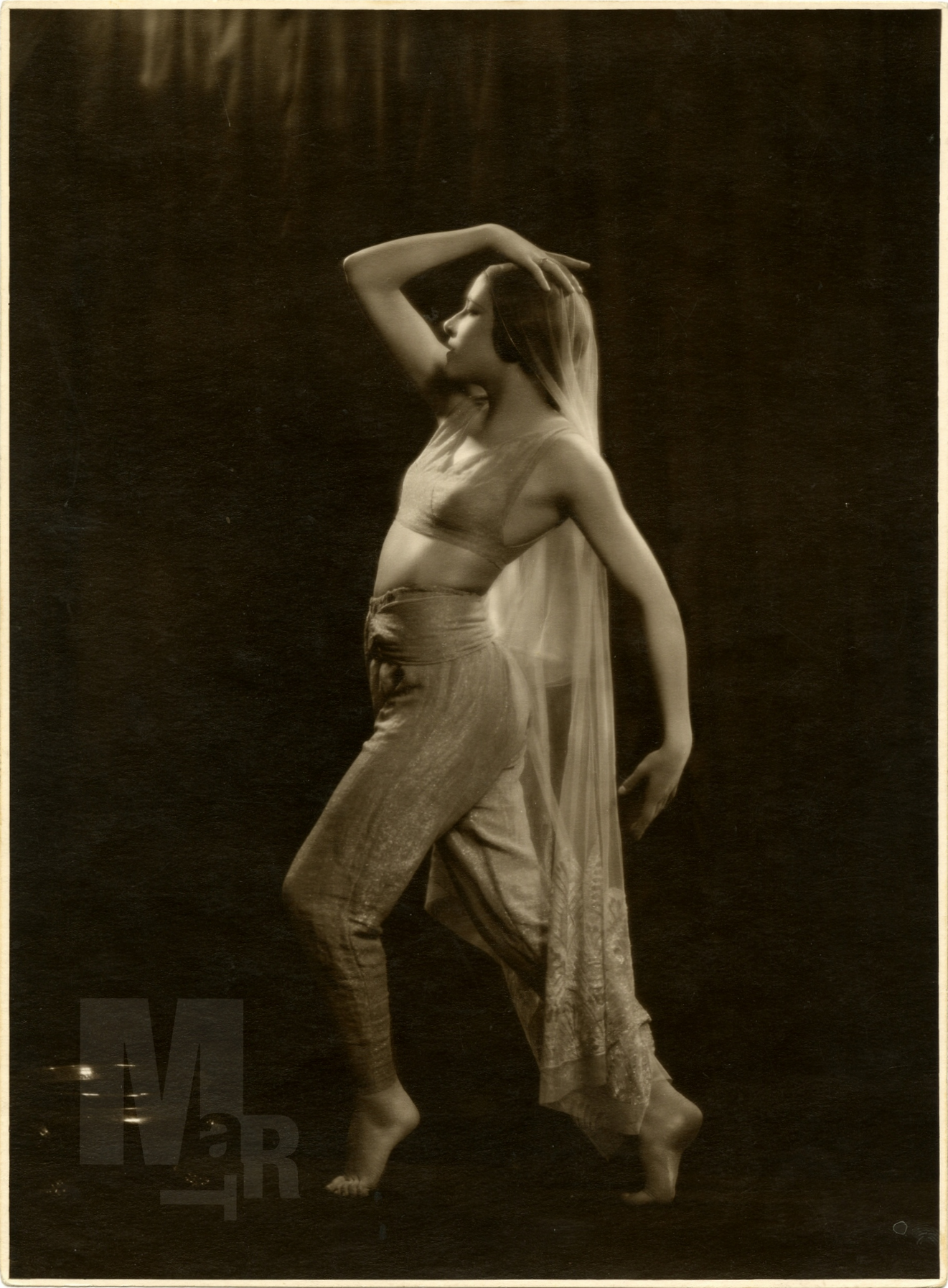

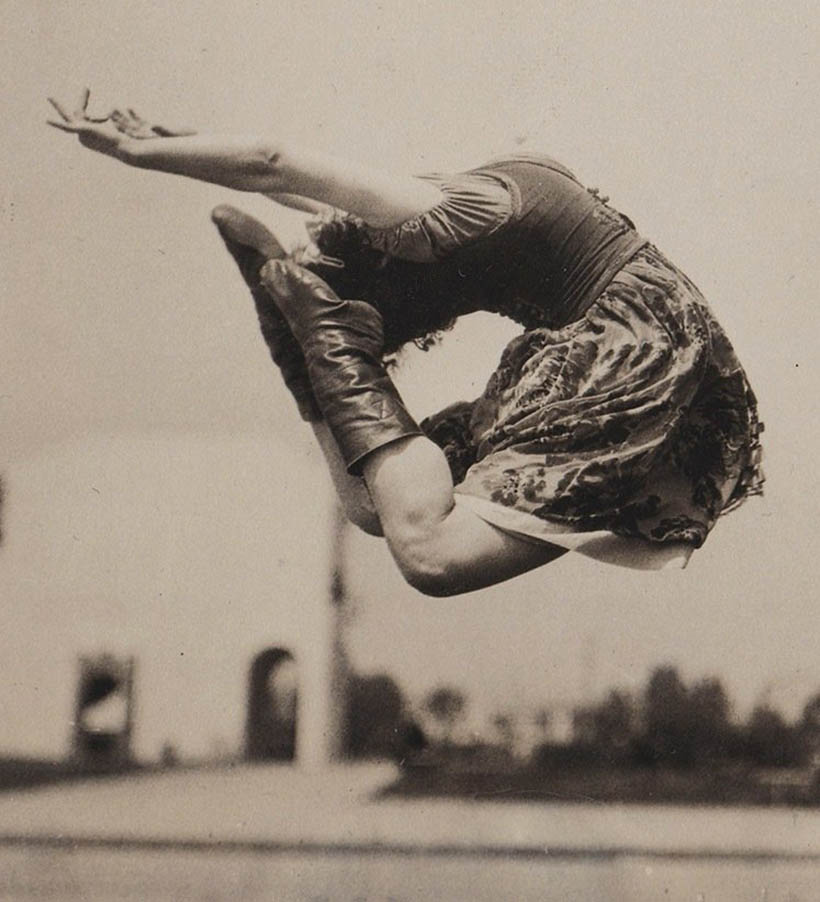

A stunning invocation of the world as viewed by the mentally ill, within minutes, as the rapid montage of the opening storm sequences dissolves into the surrealistic fantasy of the sailor’s wife dressed in an exotic costume dancing in front of an art-deco inspired backdrop featuring a large spinning ball flanked by ornate fountains, A Page of Madness bowls you over with a barrage of startling images utilising every technique known to filmmakers of the time. Even now, Kinugasa’s film seems as fresh as a daisy and when seen on the big screen, as eye-popping an experience as anything you’re likely to see released nowadays.

At the time all of this passed by unnoticed by the rest of the world, and its impact on subsequent Japanese productions seems negligible, as the film, like so many films produced in Japan during the silent period, disappeared without a trace for fifty years. Fortunately it cropped up again in the director’s garden shed in 1971, and Kinugasa struck up a fresh print, complete with a newly composed musical score and released it around the rest of the world.

For the first time A Page of Madness could be seen outside of its country of origin, affording contemporary viewers the opportunity to place the film within a historical context alongside other seminal films produced during the silent period, revealing that in many respects, Kinugasa was way ahead of the game. As the writer Vlada Petric states in an essay entitled A Page of Madness: A Neglected Masterpiece of Silent Cinema, published in the Fall 1983 edition of Film Criticism, “The fact remains that historically Kinugasa made the first full feature film whose plot development is radically subverted, whilst its cinematic structure includes virtually every film device known at the time. These devices, moreover, are used not for their own sake but to convey complex psychological content without the aid of titles”.

A despondent Kinugasa, near-bankrupt after footing the bill for the film’s production, returned to commercial production for a couple of years before embarking on his next artistic experimentation, Jujiro (Crossroads, sometimes known as Crossways, or The Slums of Yoshiwara) in 1928. Quoted from Midnight Eye, visions of Japanese cinema

In the last sequence before the final closure, a Western audience feels insecure because it has no spontaneous understanding of the Noh and may be disturbed by a suspicion that its interpretation of the mask (marked in the Western culture by negative allusions of a false beauty hiding the horrible truth) may not apply. If only you trust your perception, you will understand perfectly well what is going on in this sequence.

The man imagines himself to be laughing happily bringing a basket full of masks to the inmates and handing them out. The moment they don the masks their obsessively rhythmic movements stop; they relax. Then the man puts a mask on his deranged wife’s brooding face and dons one himself. A beautiful close-up shows man and wife with their radiant masks – hers softly smiling, his wrinkled but happy laughter – the image of a couple united, an image of happiness. The sequence is his fantasy of being able to overcome the mental separation from his wife. And to bring the deranged inmates deliverance from suffering. It functions, as intended by the authors (Kawabata tells us) indeed as an imagined happy end (and in the longer original version it worked as an indication of the happy end to be, the marriage of her daughter and her fiancé).

There are further insights if one tries to consider the Noh masks and the use the film makes of them. Noh is no ordinary stage entertainment, and a Noh mask is no ordinary prop. Noh belongs to the loftiest High culture, aristocratic in its origin, ritual in function. By using the masks, its most charged and prized element, the makers of A Page of Madness make a programmatic statement, claiming the status of High Art for their film, product of that very low class medium, the cinema. Using the masks freely, separated from their context, they make an ostentatious break with tradition. All of their implicit and explicit goals are fulfilled perfectly and to the advantage of the film because the masks are not desecrated or used in an arbitrary way. Their original power and function is realised in a different context; with their appearance, moods and rules of the Noh play are invoked and subtle affinities of the film with the Noh are accentuated.

Many Noh plays deal with human suffering, and one of the five categories of Noh plays are about madness; about people, usually women, gone mad through despair, longing, exhaustion, betrayal, grief of jealousy. The Noh has an aesthetic and dramatic side, telling these haunting stories, and has a ritual side of transforming, soothing and liberating the human mind from suffering and giving it peace. This function is invoked in the mask sequence. Okina, the Divine Old Man whose white mask Inoue dons, brings good fortune and divine blessing. It is the oldest and most sacred type of Noh mask (called hakushikijo). The ritual of the Okina dance is performed only on New Year, the highest holiday of the year, to invoke blessing and good fortune, and for the same purpose, on rare occasions like the inauguration of a new stage. Maybe it was purely a case that among the masks they could borrow from an antique dealer for the shooting there was also a white Okina, but this mask underlines the positive power of the scene approaching the protagonist into the laughing divinity who brings blessing and happiness. (Interview with Mariann Lewinsky) Quoted from Midnight Eye, visions of Japanese cinema

link to full movie on internet archive

![Giannina Censi con un costume di scena di ispirazione medieval-religiosa, ca. 1930 [# 3] | src MART · Fondo Giannina Censi](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52190820873_05416fc560_o.png)

![Giannina Censi con un costume di scena di ispirazione medieval-religiosa, ca. 1930 [# 2] | src MART · Fondo Giannina Censi](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52191060759_8467ea5708_o.png)

![Giannina Censi con un costume di scena di ispirazione medieval-religiosa, ca. 1930 [# 1] | src MART · Fondo Giannina Censi](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52190820928_fc94427917_o.png)

![Giannina Censi con un costume di scena di ispirazione medieval-religiosa, ca. 1930 [# 5] | src MART · Fondo Giannina Censi](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52189794977_d9329e5b47_o.png)

![Giannina Censi con un costume di scena di ispirazione medieval-religiosa, ca. 1930 [# 3] | src MART · Fondo Giannina Censi](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52190820863_8ca37fbf3a_o.png)

![Giannina Censi con un costume di scena di ispirazione medieval-religiosa, ca. 1930 [# 2] | src MART · Fondo Giannina Censi](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52191060744_e8b2752aaf_o.png)

![Giannina Censi con un costume di scena di ispirazione medieval-religiosa, ca. 1930 [# 1] | src MART · Fondo Giannina Censi](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52191060799_b7dd4e57ac_o.png)

![Giannina Censi con un costume di scena di ispirazione medieval-religiosa, ca. 1930 [# 5] | src MART · Fondo Giannina Censi](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52191060659_c3bbb5c87b_o.png)

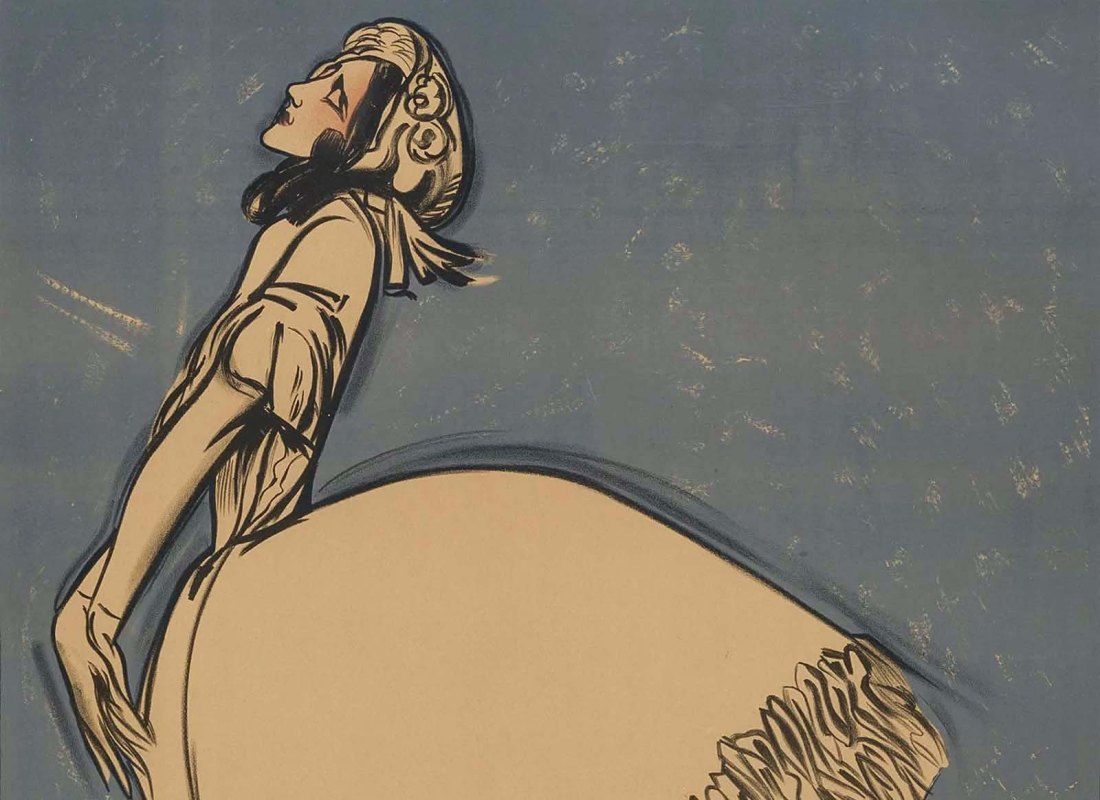

![Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) :: Théatre de Monte-Carlo; Ballet Russe; [Nijinsky]. Lithograph in colours, 1911](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52613327629_bb44094cde_o.jpg)

![Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) :: Théatre de Monte-Carlo; Ballet Russe; [Nijinsky]. Lithograph in colours, 1911](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52613161570_39fb6cfe33_o.jpg)

![Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) :: Théatre de Monte-Carlo; Ballet Russe; [Karsavina], 1911. Lithographic poster in colors on wove paper, printed by Eugène Verneau & Henri Chachoin, Paris. Severin Wunderman Family Museum | src Bonhams](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52613161620_7515a9fe2a_o.png)

![Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) :: Théatre de Monte-Carlo; Ballet Russe; [Karsavina], 1911](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/jean_cocteau_theatre_de_monte-carlo_ballet_russe_karsavina_bonhams_det.jpg)

![Jean Cocteau (1889-1963)

THÉATRE DE MONTE-CARLO, BALLET RUSSE [Karsavina]

Lithograph in colours, 1911, printed by Eugène Verneau & Henri Chachoin, Paris | src Christie's](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/52612740211_60b1398bed_o.jpg)