images that haunt us

This work, which Emil Pirchan developed using a special ink paper technique, impresses with its singular beauty. Emil Pirchan, who came from Brno and grew up in a well-off artist household, came to Vienna in 1903. The metropolis, which was currently experiencing one of its heydays, was a magnet for many artists from near and far. Back then, Pirchan studied architecture in Otto Wagner’s master class at the Academy of Fine Arts, and in the evenings he was a regular guest at the Café Museum, which was then a meeting place for the progressive artists of the Vienna Secession. Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, Josef Olbrich and also his teacher Otto Wagner met here and debated about art. Pirchan later vividly remembered the “exuberance of the feeling of belonging to a liberated new art” (Bau und Bild, Bühne und Buch. Erinnerungen an mich, Vienna 1941, unpublished manuscript).

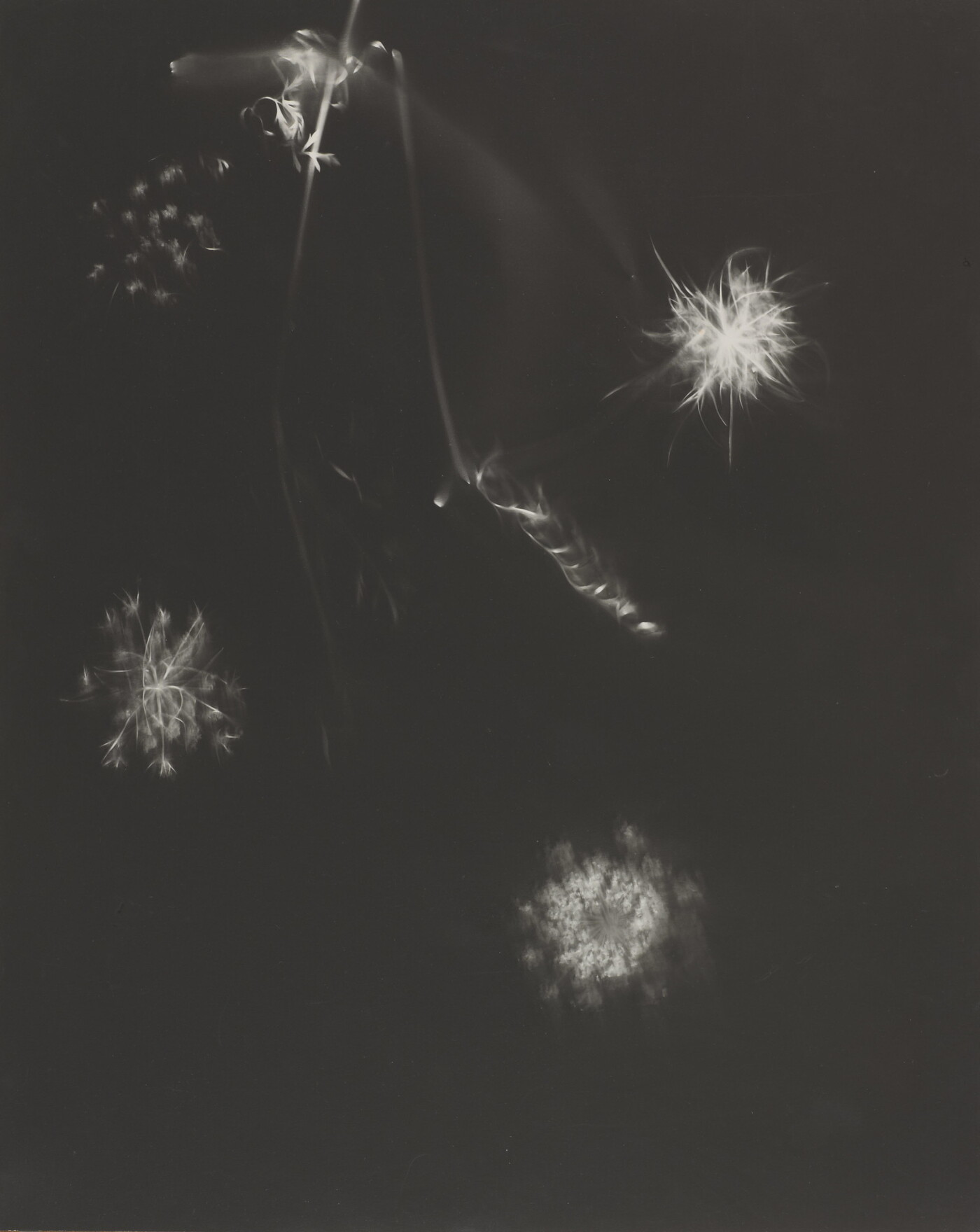

At that time, Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser and Leopold Stolba, members of the Secession, were experimenting with the production of dipped paper (Tunkpapiere). They modified the process originally developed in the Orient and created poetic compositions in which birds, amphibians, fish and plants suddenly appear in recurring wave patterns. The Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna keeps an excellent collection of these paper works from the years 1903 to 1906. These works must have been a source of inspiration for the young student Emil Pirchan, who evidently immediately recognized the potential of the technique and developed it further. In the marbling technique, a sheet of paper records an “image” that was created with colors on the surface of the water in the marbling bath. While the historical marbled papers were ornamental and could be cut to size for different purposes, the sheets of the Vienna Secession were designed as images, with a specific format and a defined image area. Pirchan’s dipped papers are also designed as images, but he breaks away from representationalism. He lets the colors sometimes glide gently onto the surface, sometimes drips them into the water bath from above, perhaps with the help of a pipette. Blurred areas of color compete with circular dots of color, which expand explosively due to additional violet drops of color in their center, creating the impression of a brilliant firework display. The monotypes created in this way are therefore largely determined by chance, by the unforeseen flowing movements of the pigments. Pirchan’s abstract compositions unfold an unexpected magic and are far ahead of their time. It was only years later that Wassily Kandinsky brilliantly shattered the representational into colorful shapes and lines. / from : Bassenge Auktion 121

The painter, commercial artist, architect, stage designer and writer Emil Pirchan was rediscovered in 2019 at the Museum Folkwang, Essen through an exhibition that was afterwards shown at the Leopold Museum in Vienna. The artist’s ink papers (Tunkpapiere) were a special surprise at the exhibition. They are closely linked to “Vienna around 1900”, where the artist, who was born in Brno, became a master student of the famous architect Otto Wagner in 1903. He is also closely connected to the vibrant art scene in the heart of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy through his great-cousin Josef Hoffmann, who rose to fame in 1903 as one of the co-founders of the legendary Wiener Werkstätte. Pirchan’s ink papers are unthinkable without the Vienna Secession and its willingness to experiment.

The present work, together with other inked papers by Pirchan, adorned the hall in his house in Brno. A historical photograph from 1907 shows the interior, for which Pirchan designed the entire furnishings, from the furniture to the flower vase, in the spirit of an overall concept (see exhibition catalogue Emil Pirchan. A universal artist of the 20th century, Wädenswil 2018, fig. p. 158-159, our work hangs in the top row, left). The compositions presented there in white, square frames show an effortless oscillation between closeness to nature and abstraction, a gliding and flowing of the motifs, which are sometimes reminiscent of exotic flowers and then again surprise with completely abstract, non-representational structures. Emil Pirchan’s inked papers are autonomous works that stand in their own right and are in no way inferior to Koloman Moser’s best experiments with color and form. And they give an idea of how Max Ernst created his oscillating universe with curved and branched lines. / Bassenge Auktion 121

Der Blumenstrauß. Die vergängliche Pracht

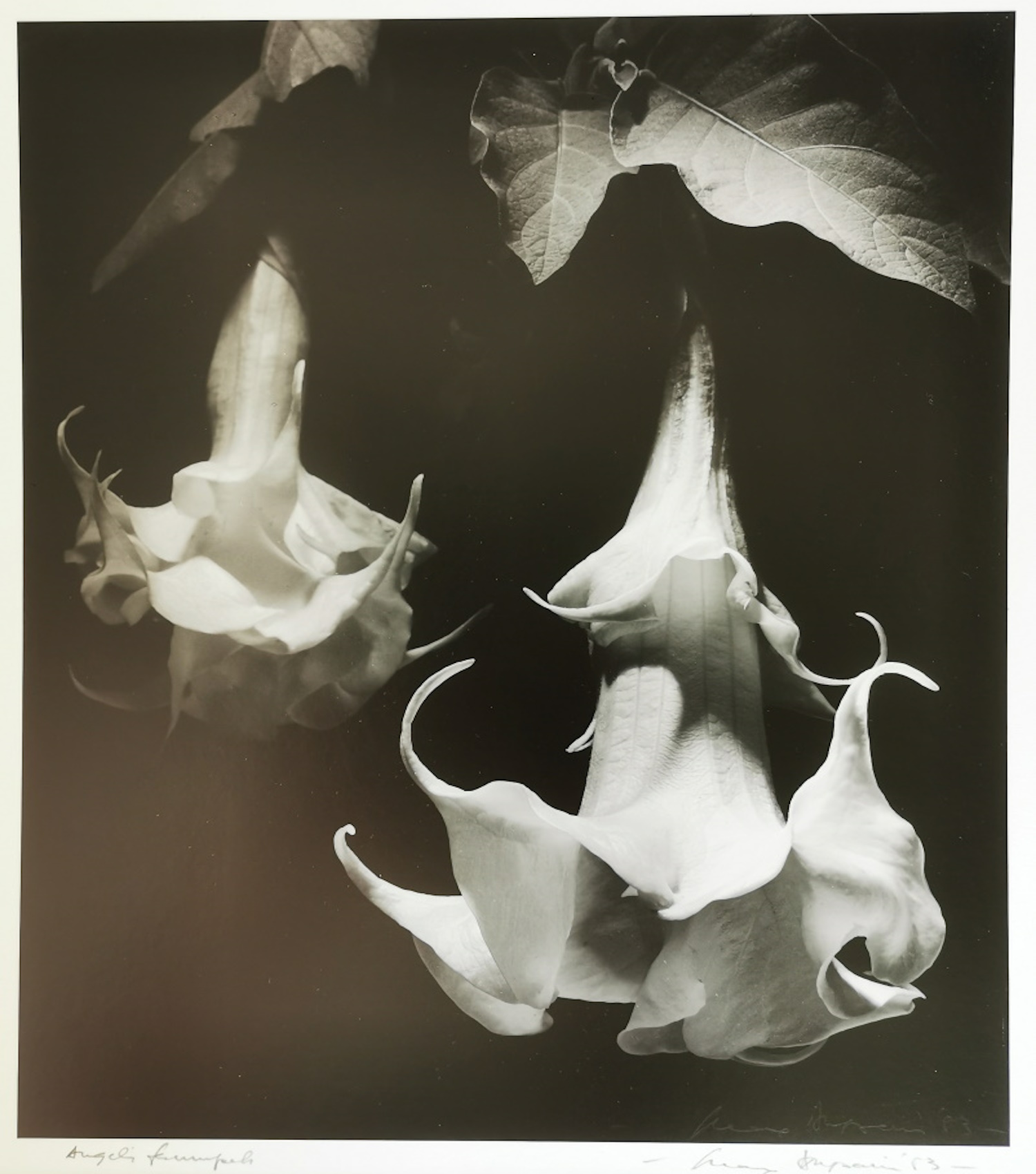

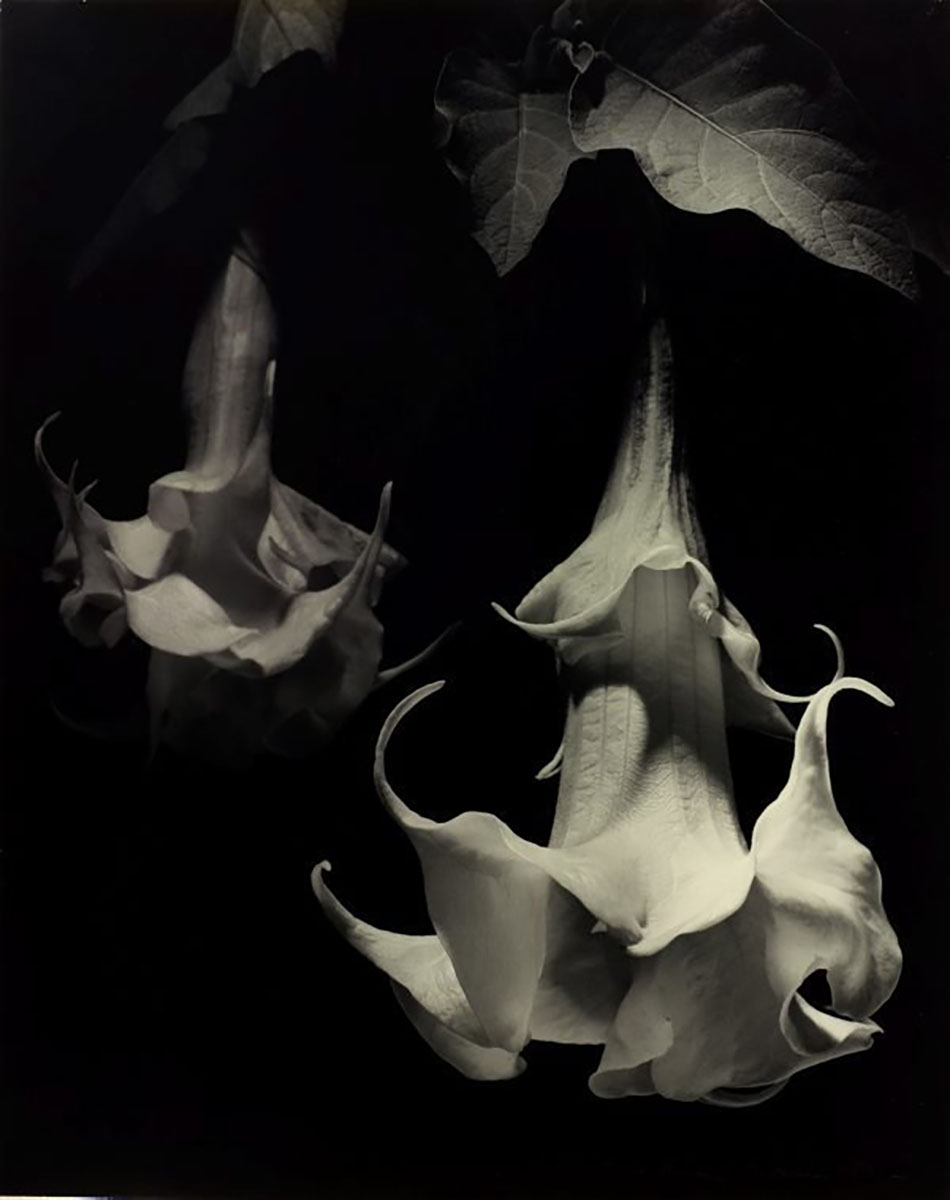

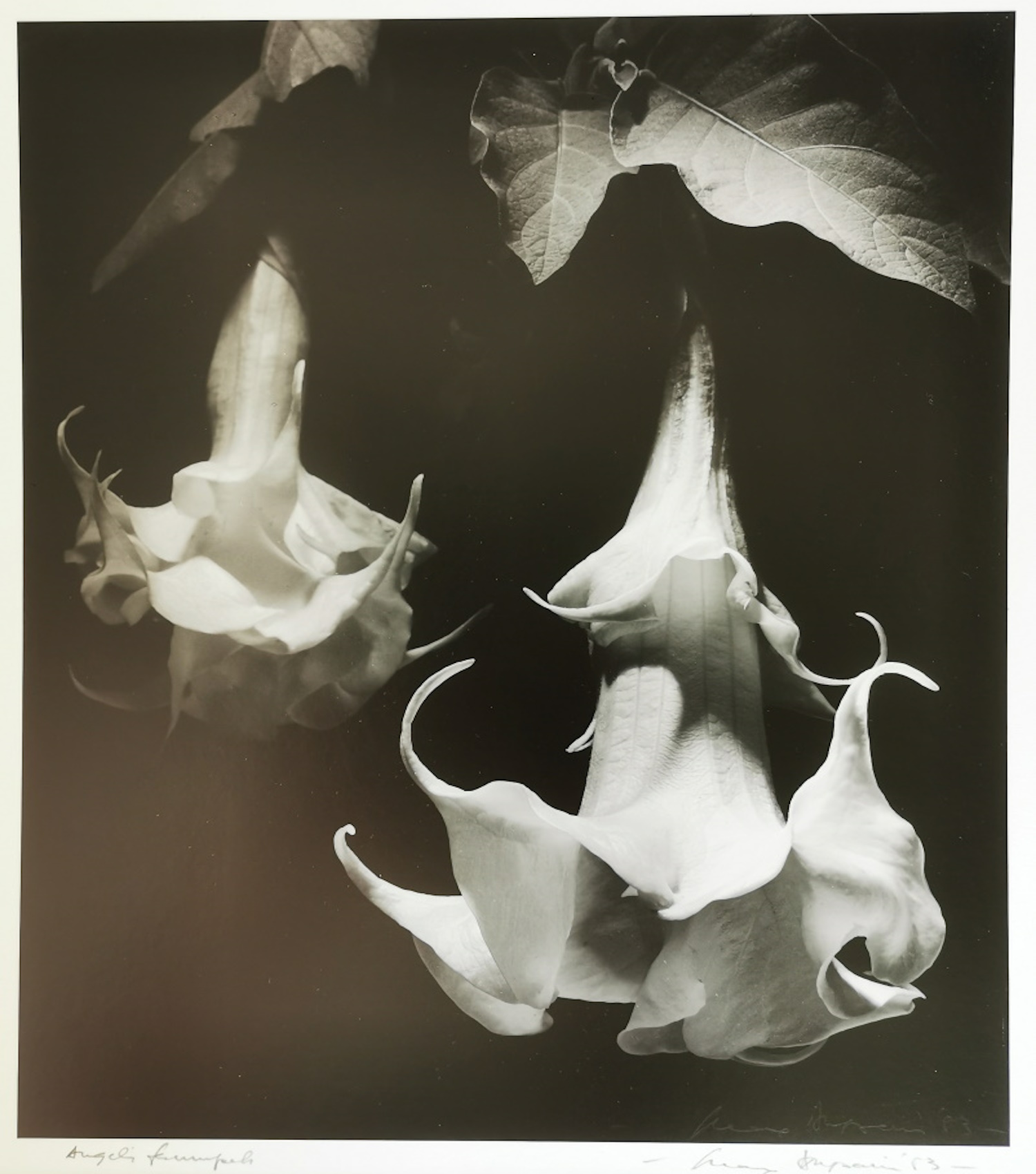

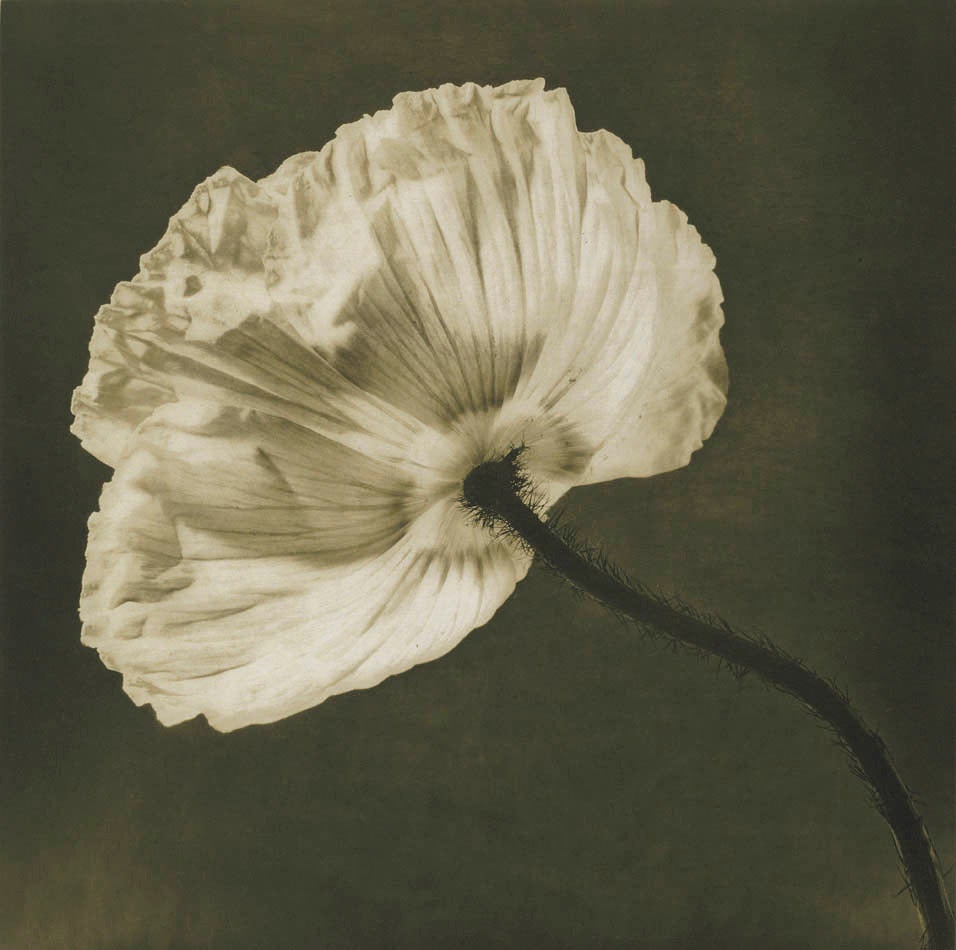

Fotografie von den Anfängen bis heute

17. Mai bis 29. Juni 2024

anlässlich der düsseldorf photo+ Biennale for Visual and Sonic Media

Mit Nobuyoshi Araki, Max Baur, Boris Becker, Ute Behrend, Viktoria Binschtok, Peter Bömmels, Tim Berresheim, Natalie Czech, Michael Dannenmann, Sam Evans, Jan Paul Evers, Jitka Hanzlová, Axel Hütte, Leiko Ikemura, Benjamin Katz, Annette Kelm, Karin Kneffel, Maximilian Koppernock, August Kotzsch, Heinrich Kühn, Kathrin Linkersdorff, Robert Mapplethorpe, Hartmut Neumann, Roland Schappert, Luzia Simons, Josef Sudek, Michael Wesely, Dr. Wolff+Tritschler und einigen anonymen alten Fotoarbeiten.

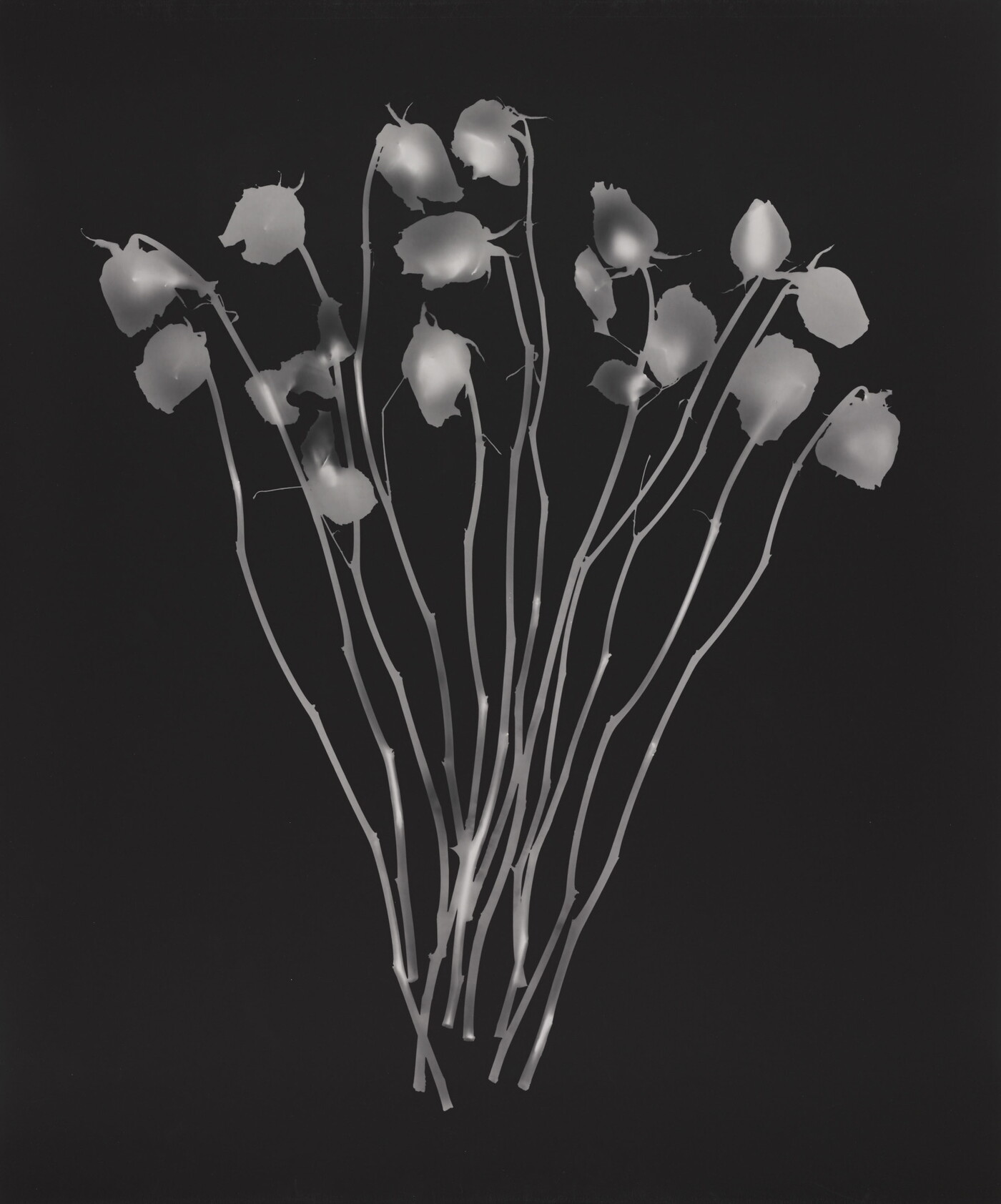

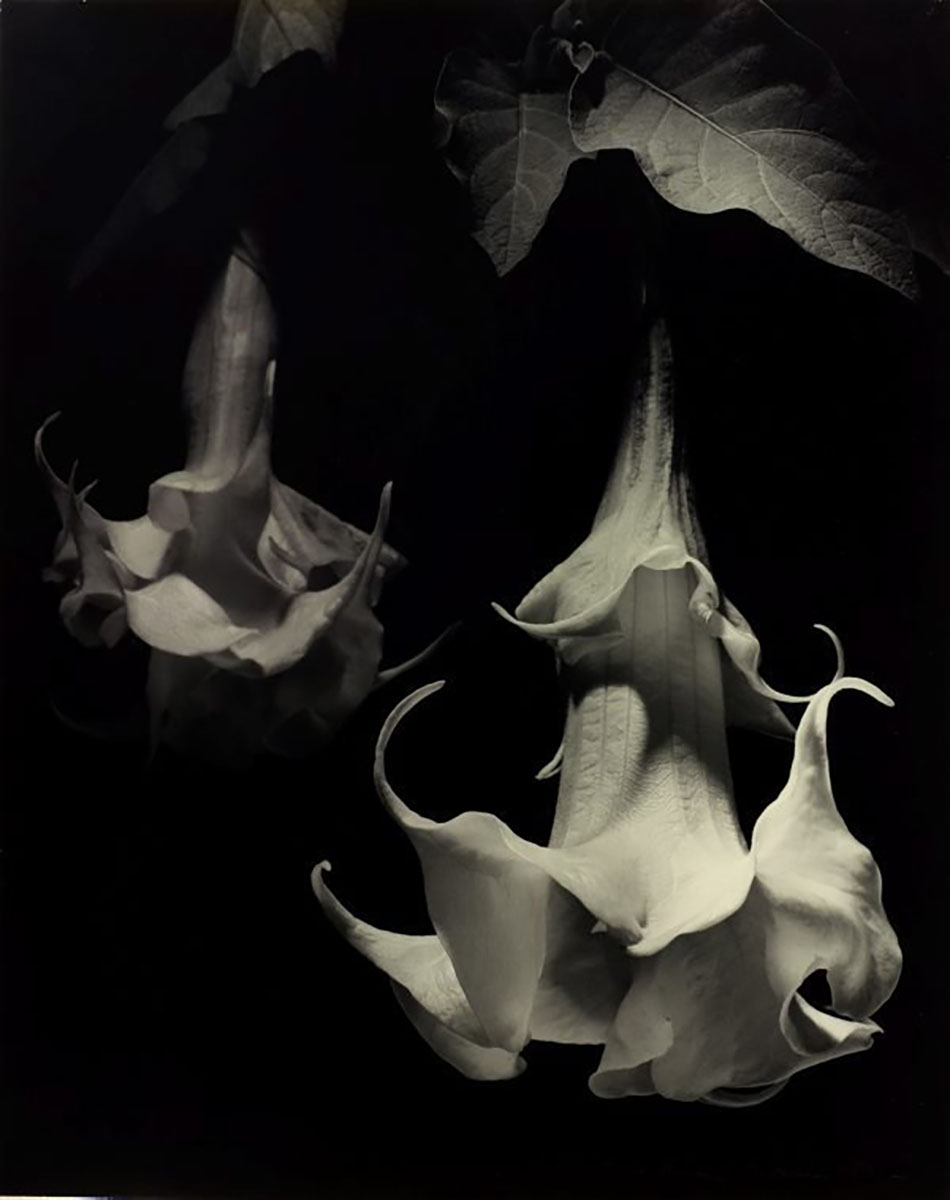

Der Blumenstrauß als künstlerische Installation, die der Fotografie vorausgeht, steht im Fokus dieser Gruppenausstellung.

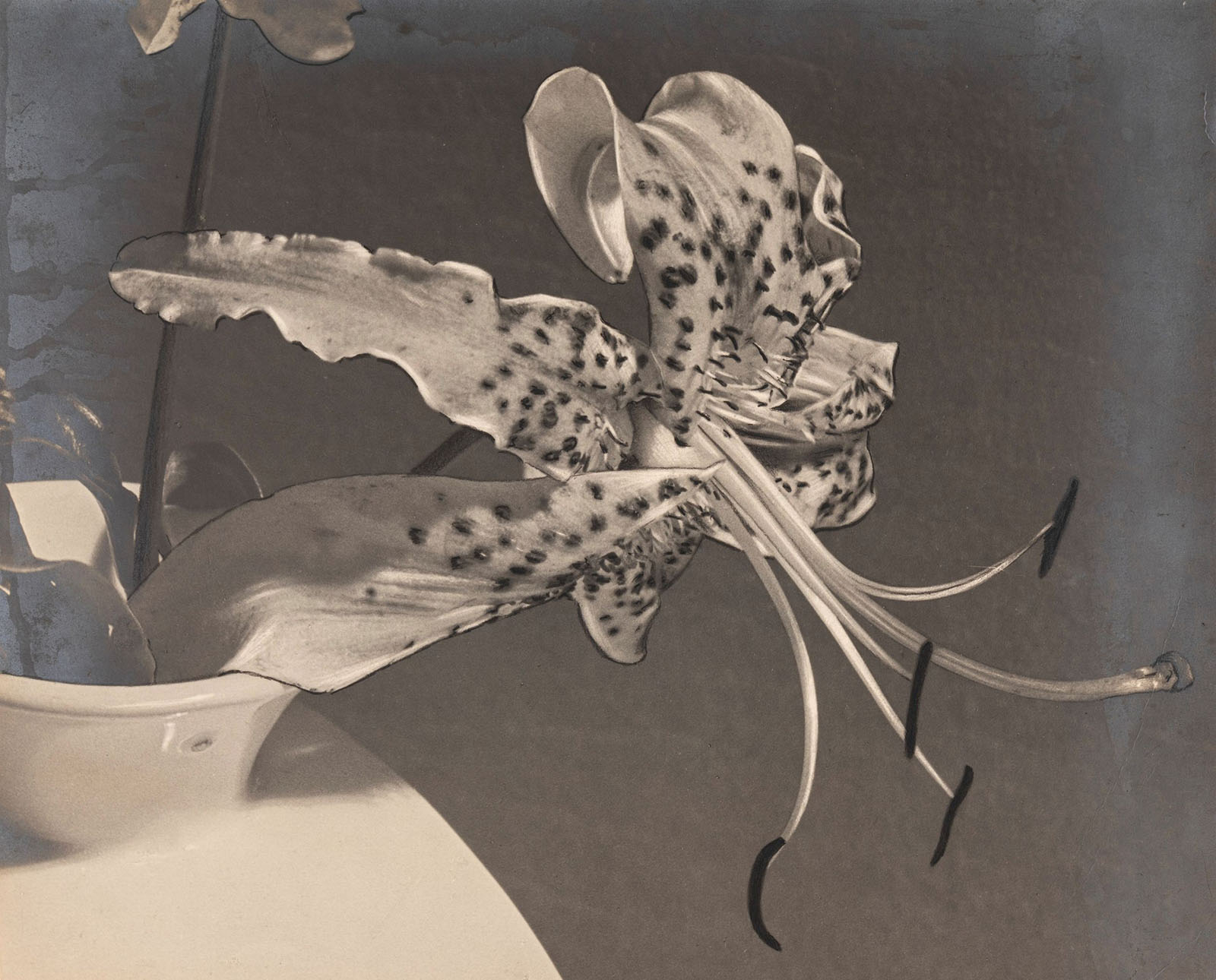

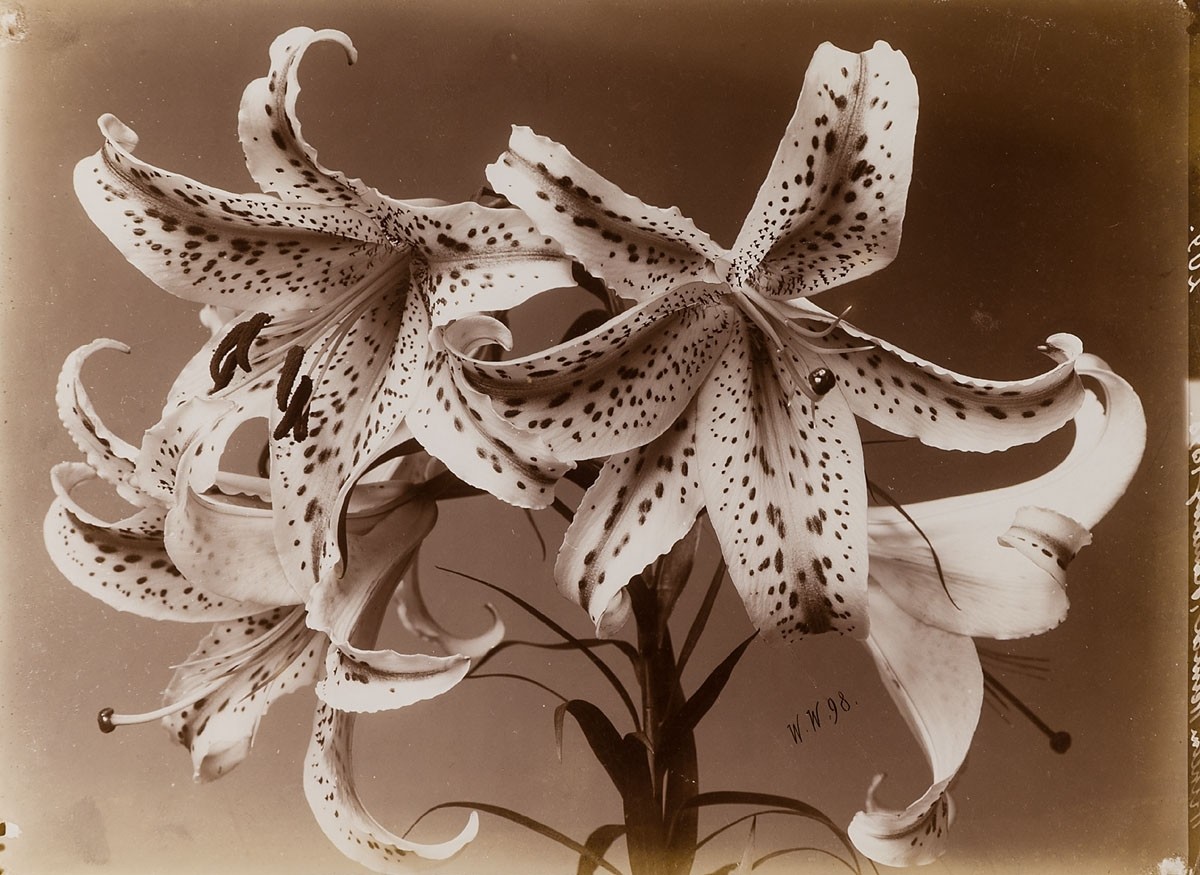

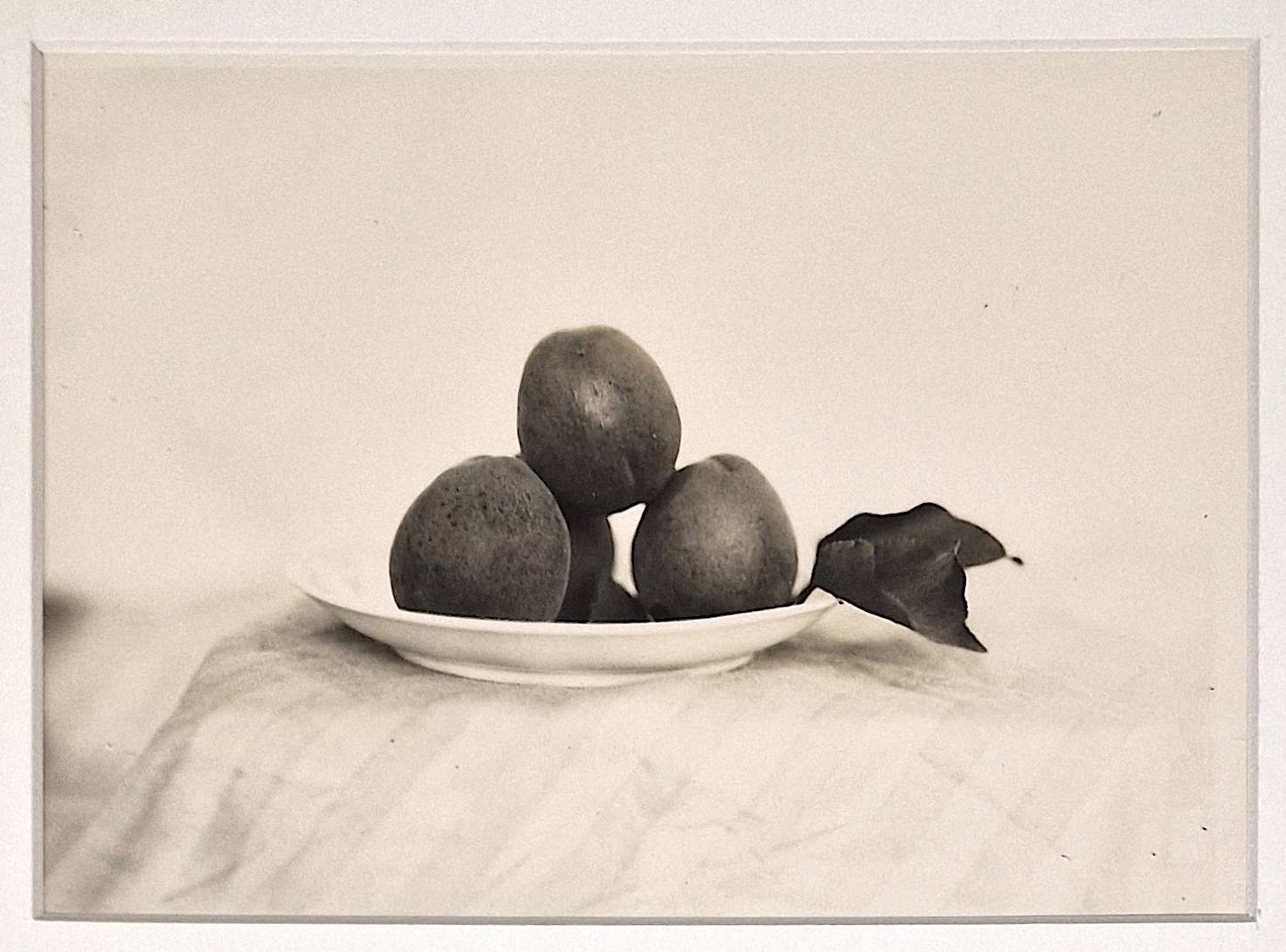

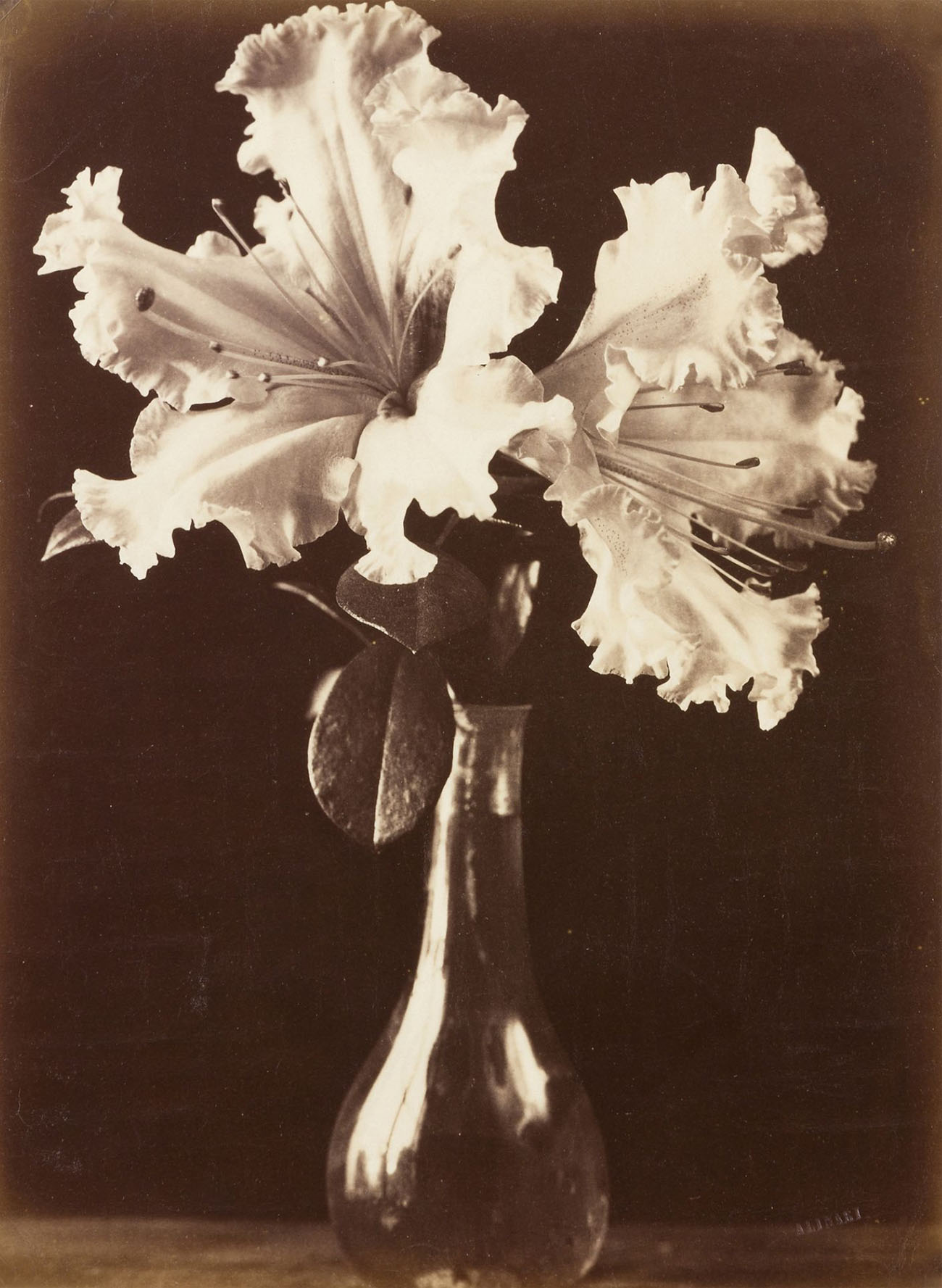

Als klassisches Thema des Stilllebens hat der Blumenstrauß seinen Reiz bis in die Gegenwart nicht verloren. Die arrangierten Fotos von Blumensträußen Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts sind als Vorläufer der inszenierten Fotografie zu verstehen.

Mit diversen fotografischen Positionen wird der Bogen von historischer Fotografie, beispielsweise von Heinrich Kühn, bis hin zu computerbasierter Fotografie von Tim Berresheim gespannt. Anhand dieses Bildsujets wird auch die Veränderung der technischen und inhaltlichen Möglichkeiten von Fotografie aufgezeigt.

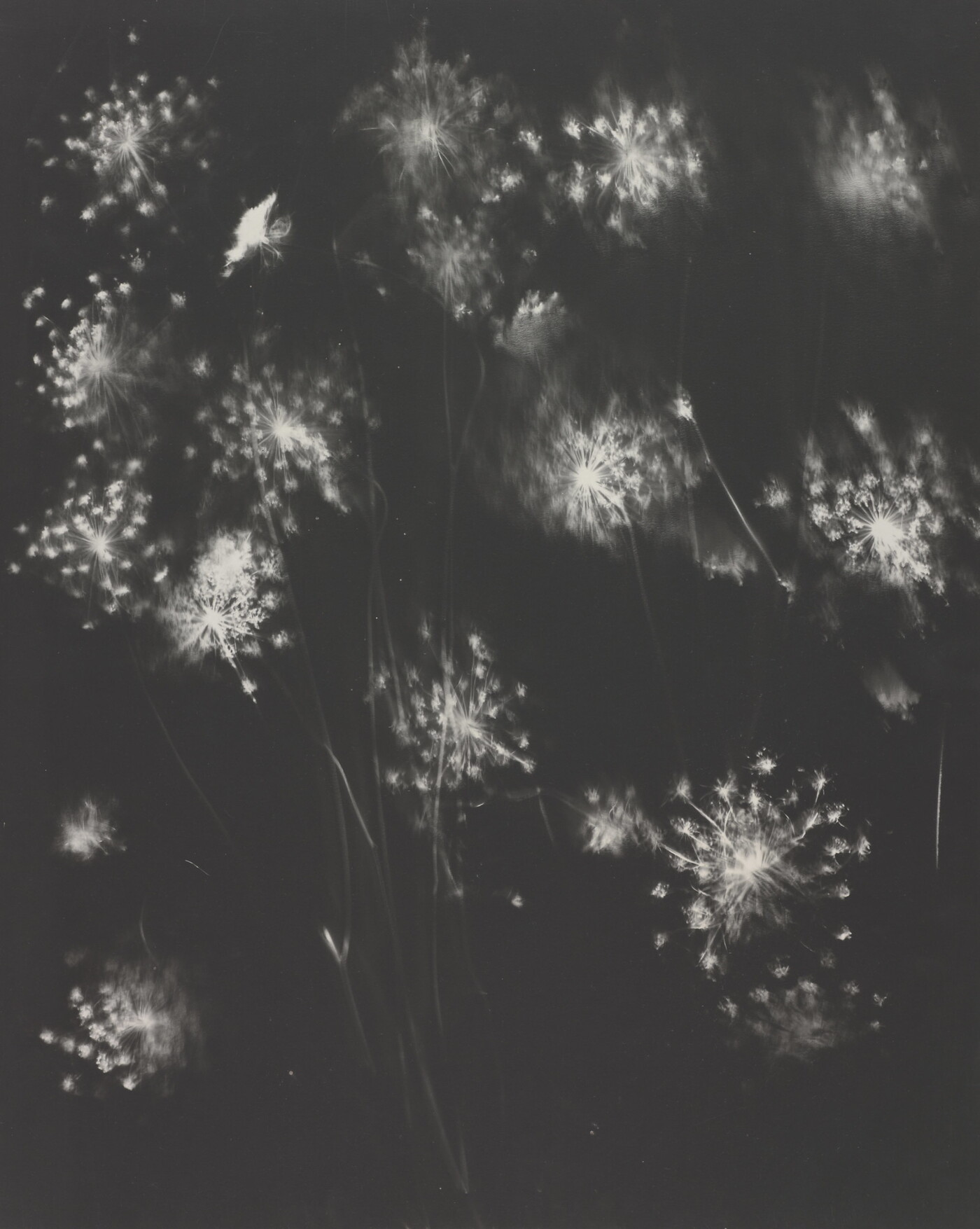

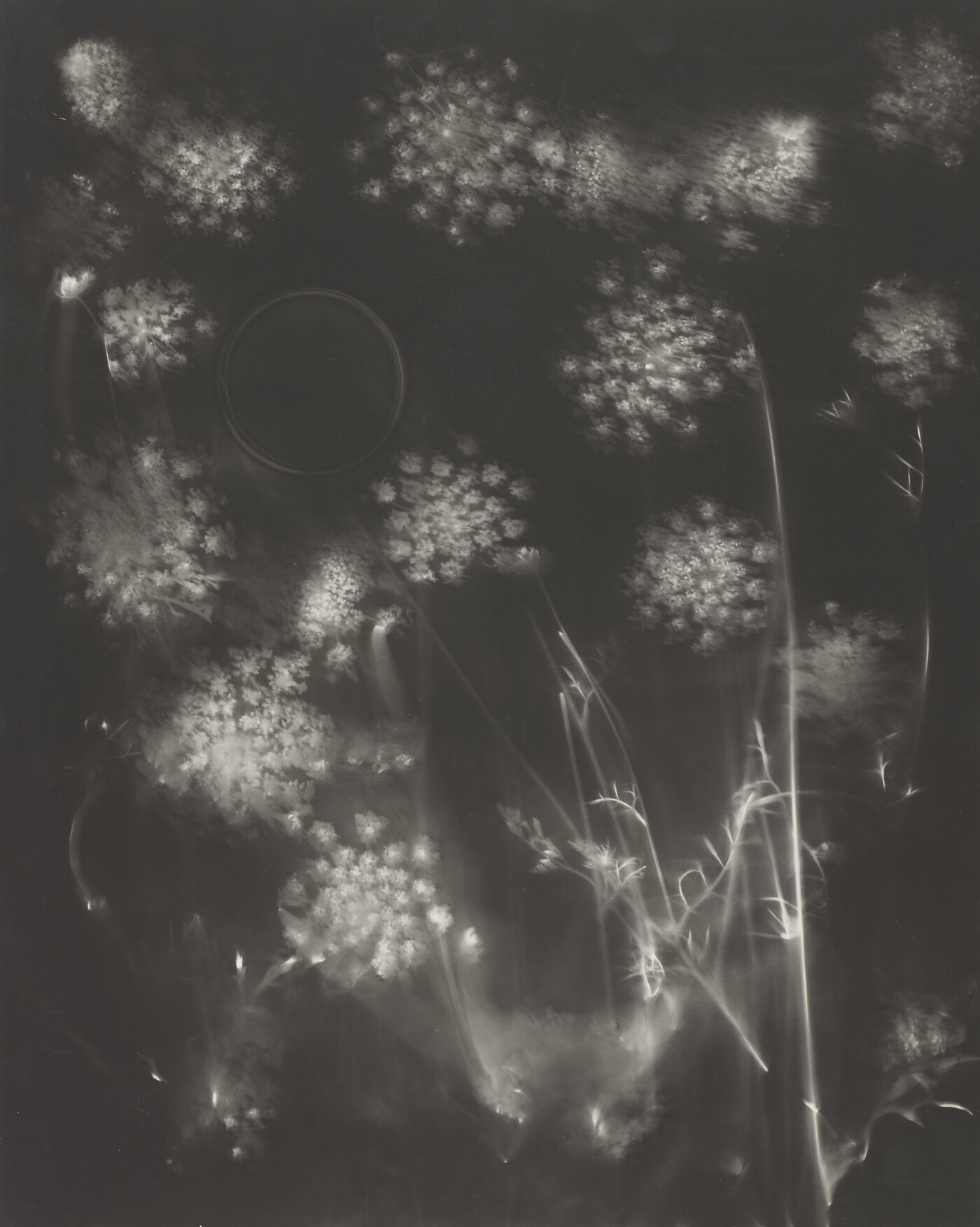

Die zeitgenössische „Blumenstraußfotografie“ geht weit über die Natur- oder Dokumentarfotografie hinaus. So haben die Fotokünstler in unterschiedlicher Ausprägung die skulpturale, malerische und konzeptuelle Möglichkeit dieses Stilllebens ausgelotet und hinterfragt.

Seit Beginn des 17. Jahrhunderts ist der Blumenstrauß in der Malerei als Stilleben in all seiner arrangierten Pracht gegenwärtig und oft sinnbildlich für die Vergänglichkeit allen Seins dargestellt. Die Fotografie hat die Möglichkeit, den Prozess des Vergänglichen zu begleiten, und oft sind es die bereits verwelkten Blumen, die einen besonderen Reiz in der Wirklichkeitswahrnehmung ausmachen. Nichts zeigt die Wirklichkeit frappierender als die Vergänglichkeit.

quoted from Der Blumenstrauß: Die Vergängliche Pracht ~ Beck & Eggeling

A Bouquet of Flowers. Transient Beauty

Photography from the beginnings to the present day

17th May until 29th June 2024

on the occasion of düsseldorf photo+ Biennale for Visual and Sonic Media

With Nobuyoshi Araki, Max Baur, Boris Becker, Ute Behrend, Viktoria Binschtok, Peter Bömmels, Tim Berresheim, Natalie Czech, Michael Dannenmann, Sam Evans, Jan Paul Evers, Jitka Hanzlová, Axel Hütte, Leiko Ikemura, Benjamin Katz, Annette Kelm, Karin Kneffel, Maximilian Koppernock, August Kotzsch, Heinrich Kühn, Kathrin Linkersdorff, Robert Mapplethorpe, Hartmut Neumann, Roland Schappert, Luzia Simons, Josef Sudek, Michael Wesely, Dr. Wolff+Tritschler and a selection of anonymous historical photographs.

The bouquet of flowers as an artistic installation that precedes photography is the focus of this group exhibition.

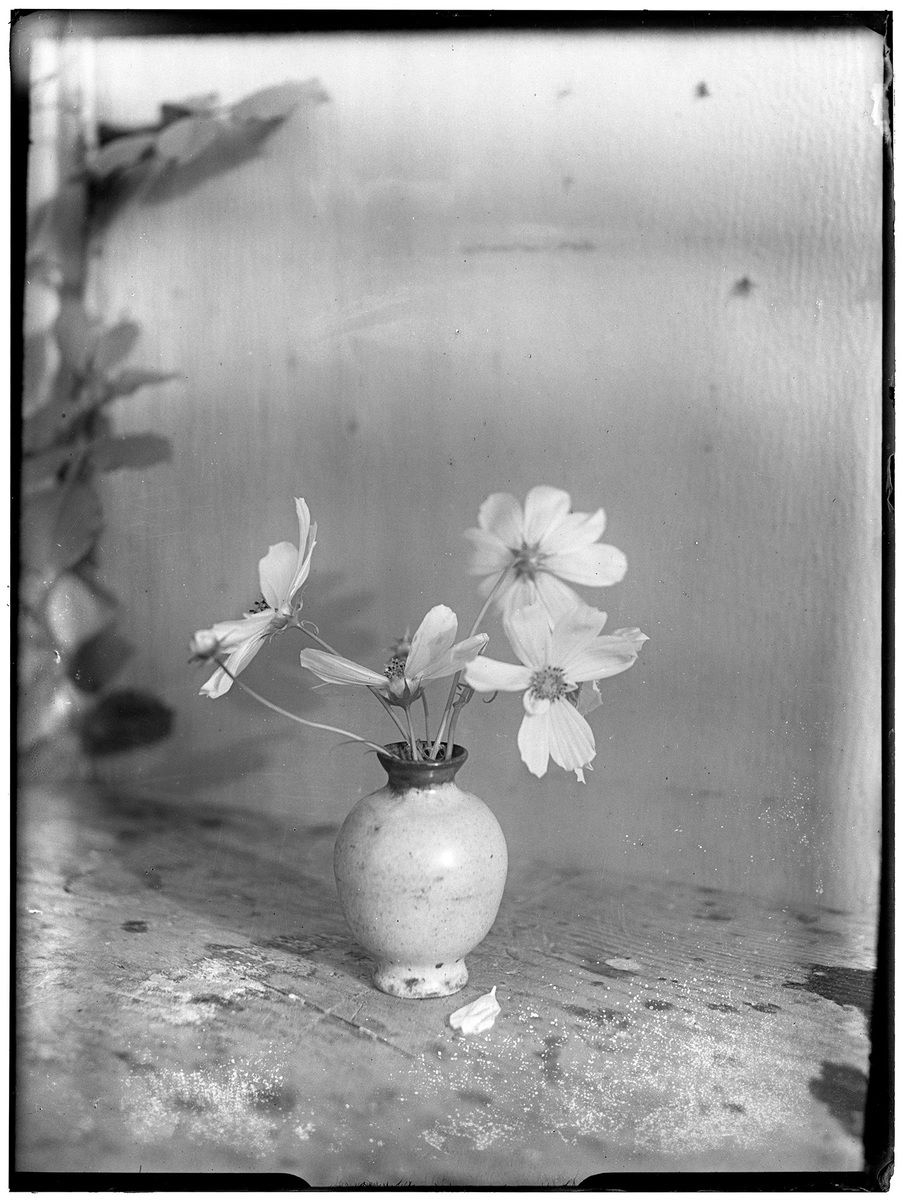

As a classic still life subject, the bouquet of flowers has not lost its appeal to the present day. The arranged photographs of bouquets of flowers in the mid-19th century are to be understood as precursors of staged photography.

With various photographic positions, the exhibition ranges from historical photography, for example by Heinrich Kühn, to computer-based photography by Tim Berresheim. This pictorial subject is also used to demonstrate the changes in the technical and content-related possibilities of photography.

Contemporary “bouquet photography” goes far beyond nature or documentary photography. Photographic artists have explored and scrutinized the sculptural, painterly and conceptual possibilities of this still life to varying degrees.

Since the beginning of the 17th century, the bouquet of flowers has been present in painting as a still life in all its arranged splendour, often symbolizing the transience of all existence. Photography has the opportunity to accompany the process of transience, and it is often the flowers that have already withered that create a special charm in the perception of reality. Nothing shows reality more strikingly than transience.