![André Steiner (Andor Steiner) :: La pente [The Slope], Lily, Roscoff, 1933. | L'amour et la photographie · Musée Nicéphore Niépce](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/andre-steiner-la-pente-lily-1933-c2a9-nicole-steiner-bajolet.jpg)

images that haunt us

![André Steiner (Andor Steiner) :: La pente [The Slope], Lily, Roscoff, 1933. | L'amour et la photographie · Musée Nicéphore Niépce](https://unregardoblique.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/andre-steiner-la-pente-lily-1933-c2a9-nicole-steiner-bajolet.jpg)

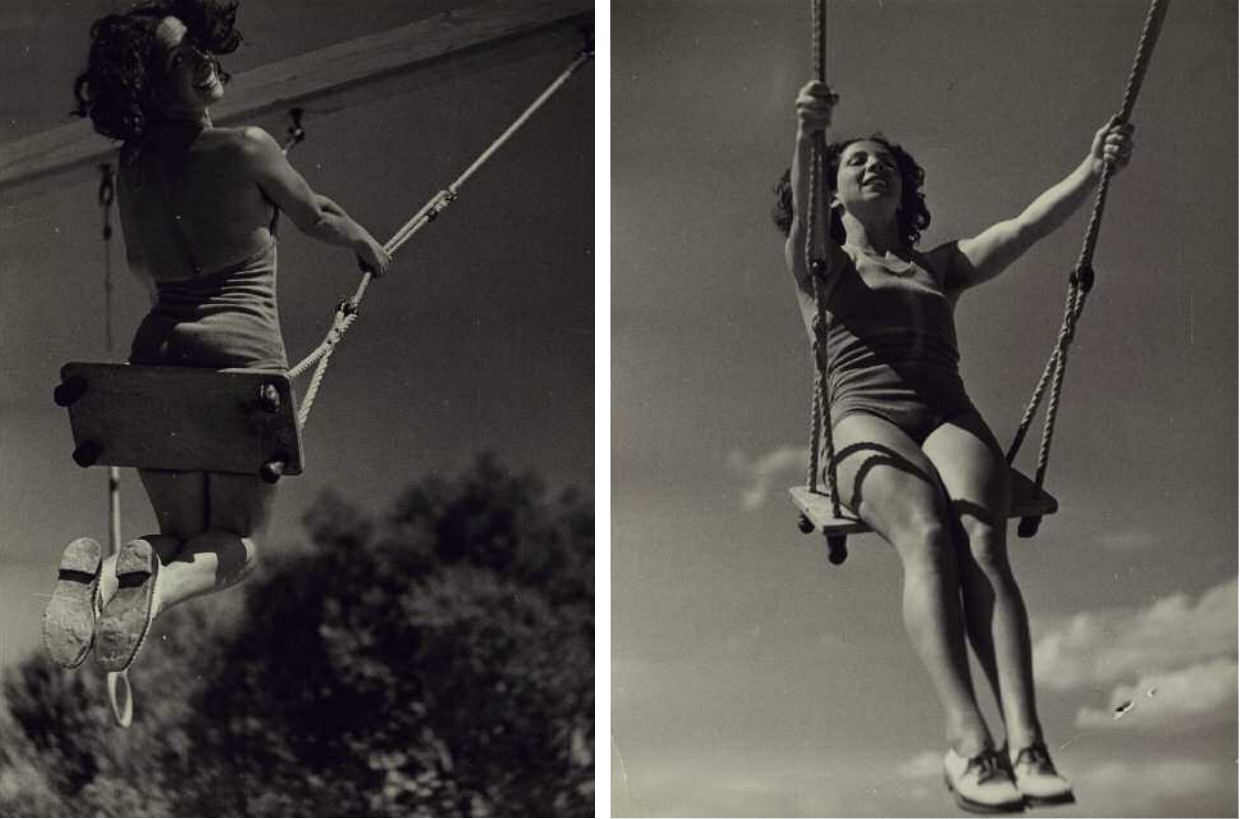

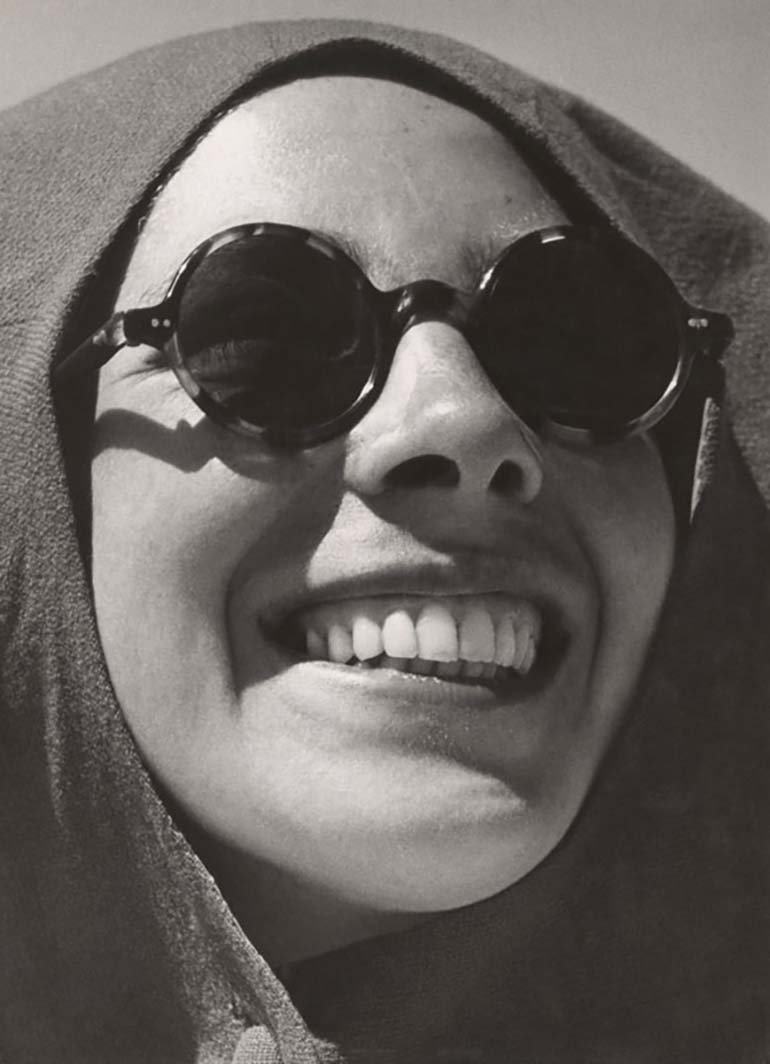

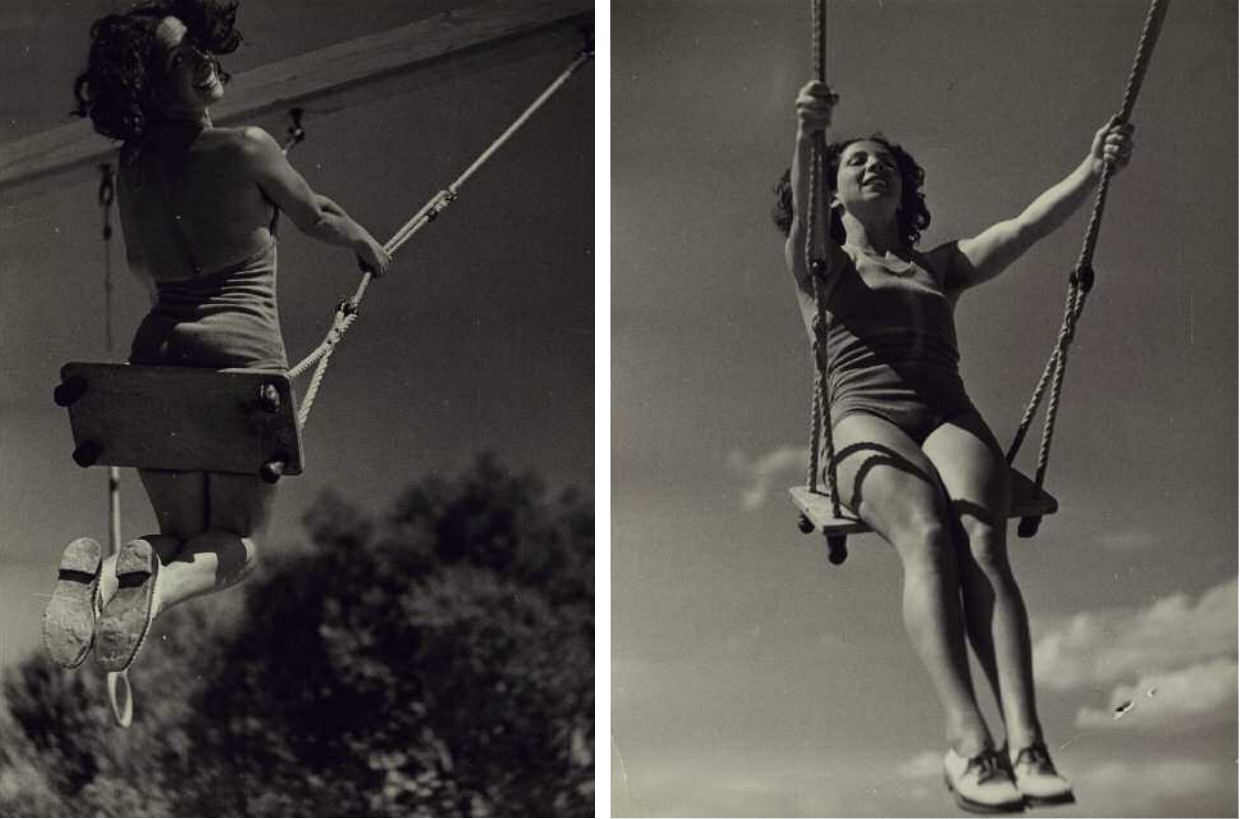

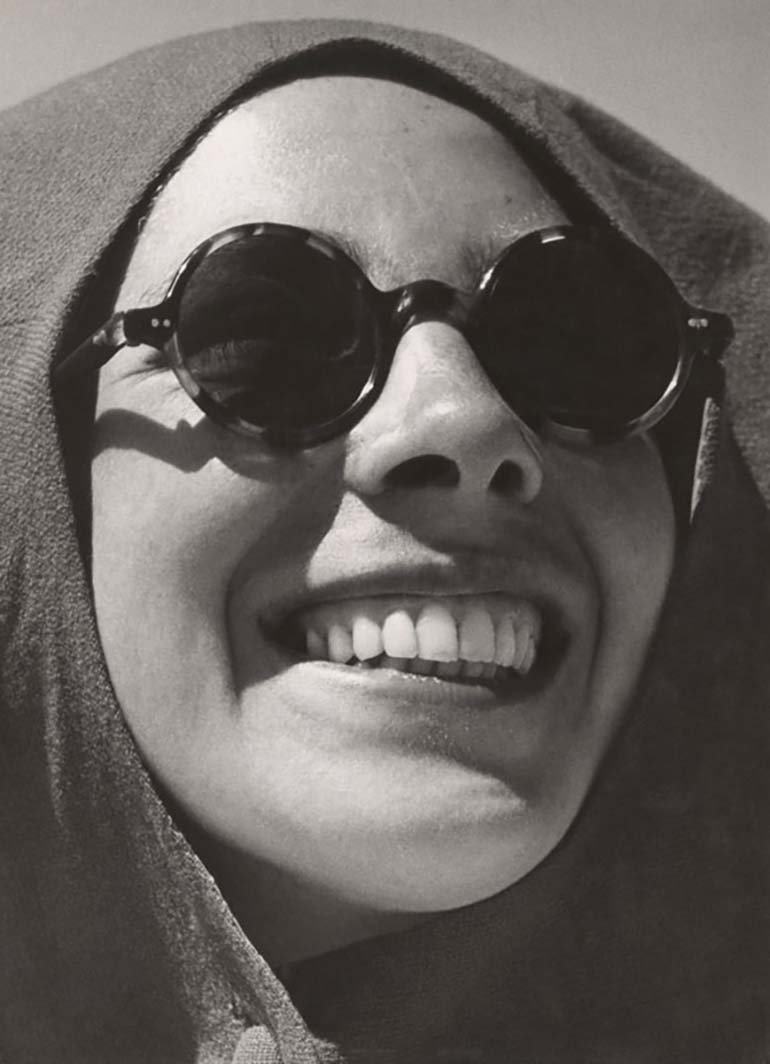

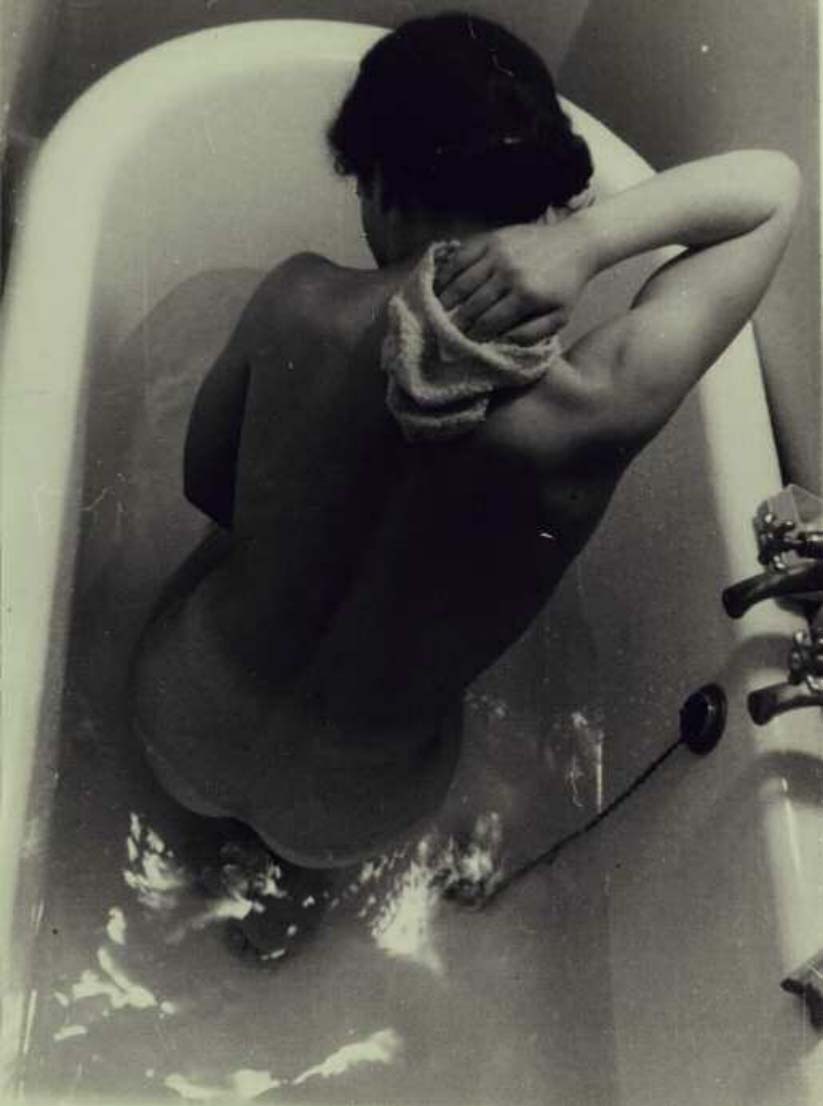

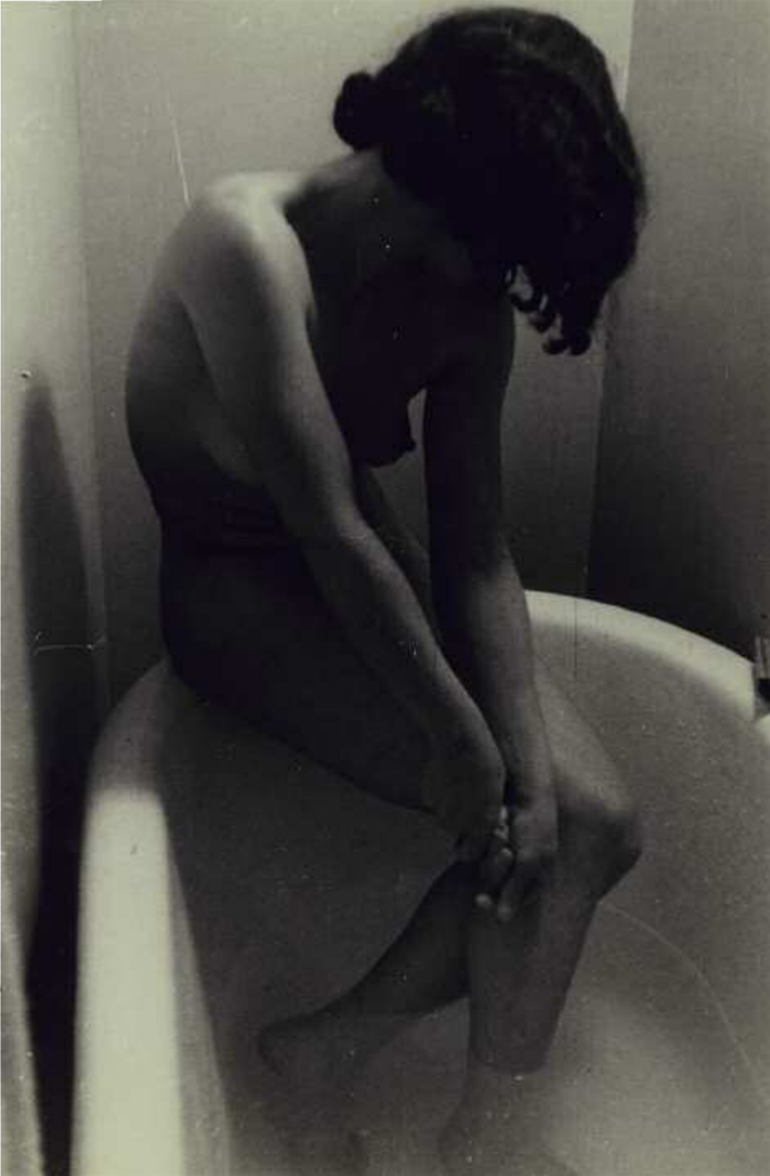

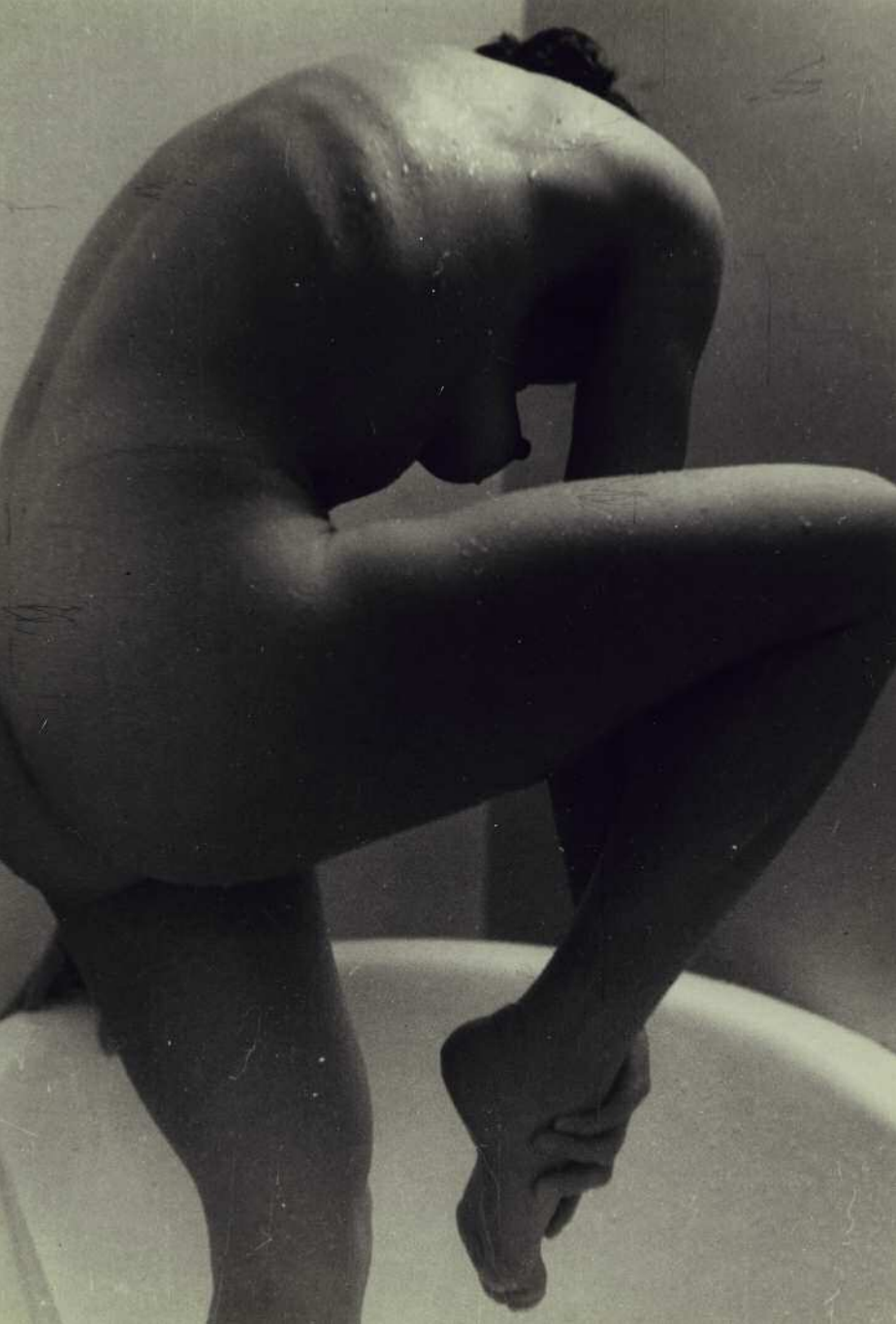

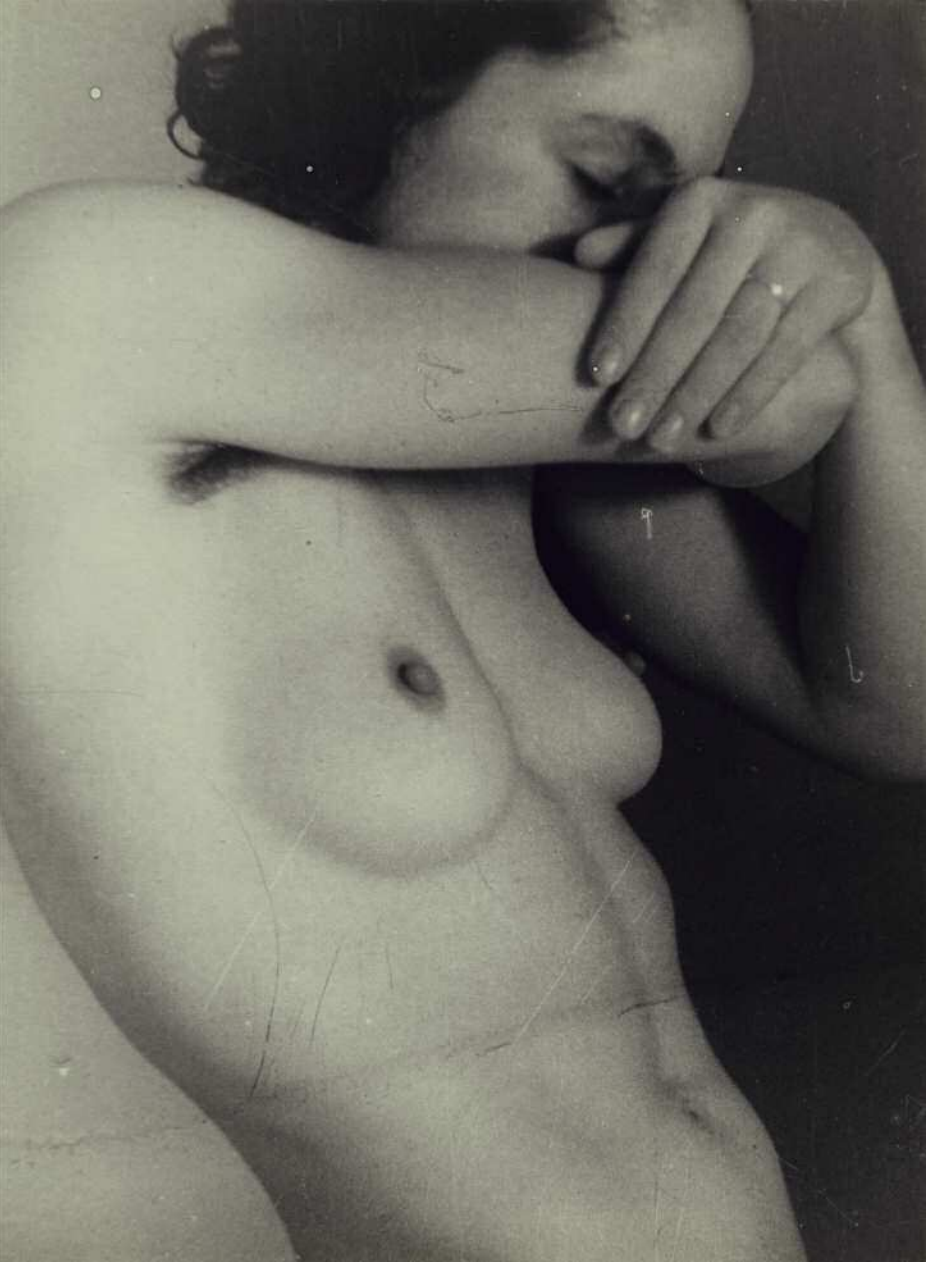

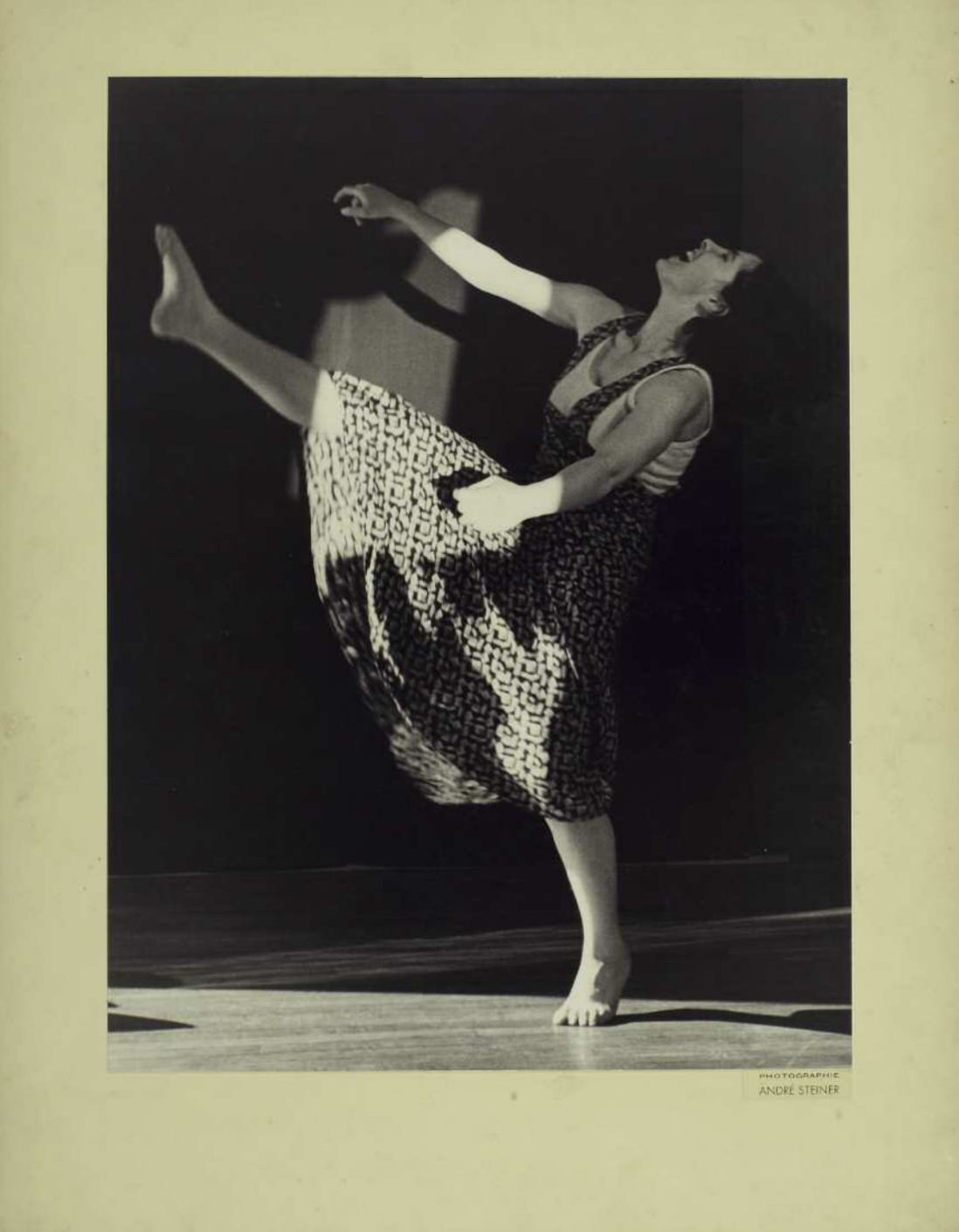

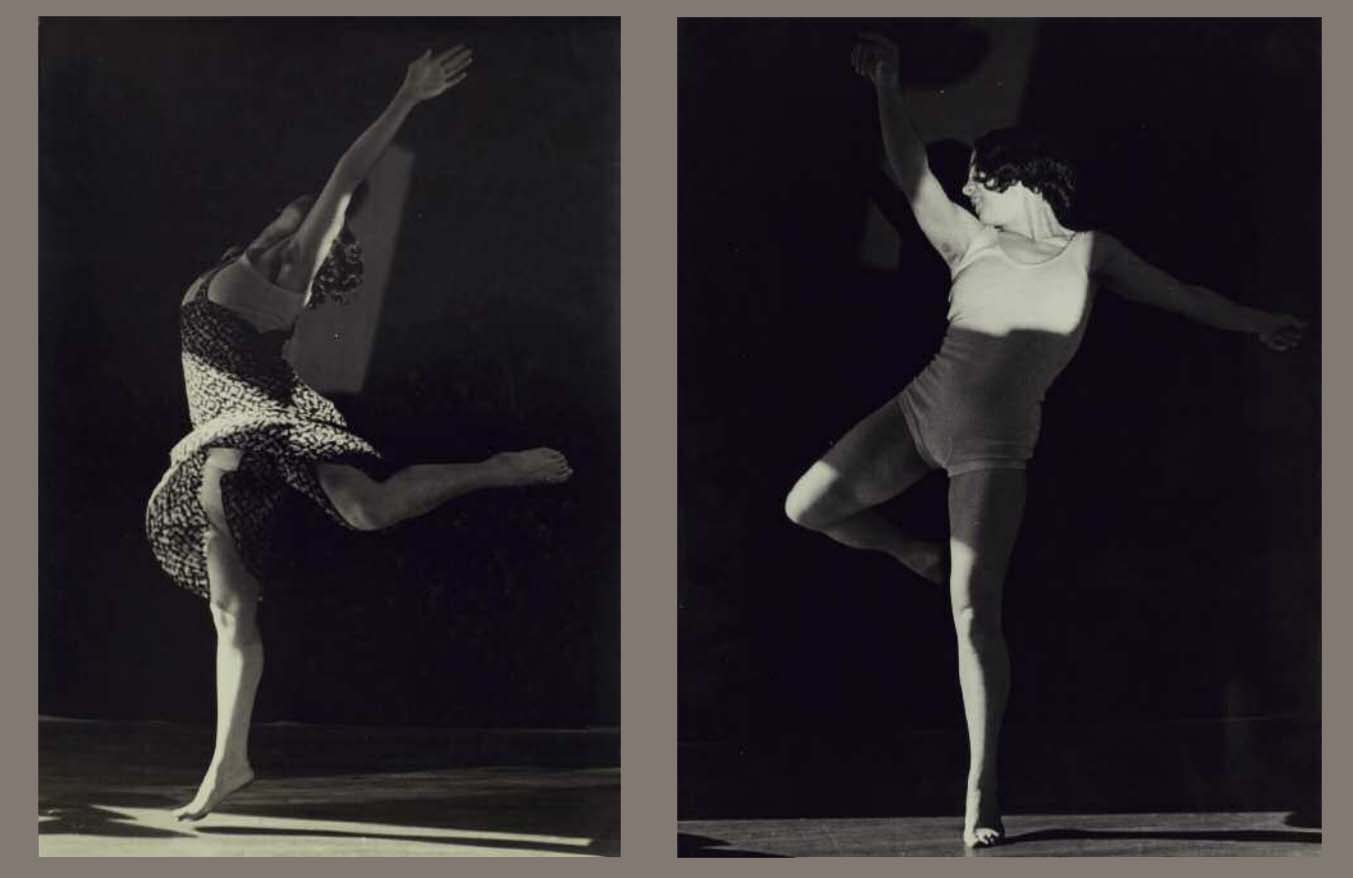

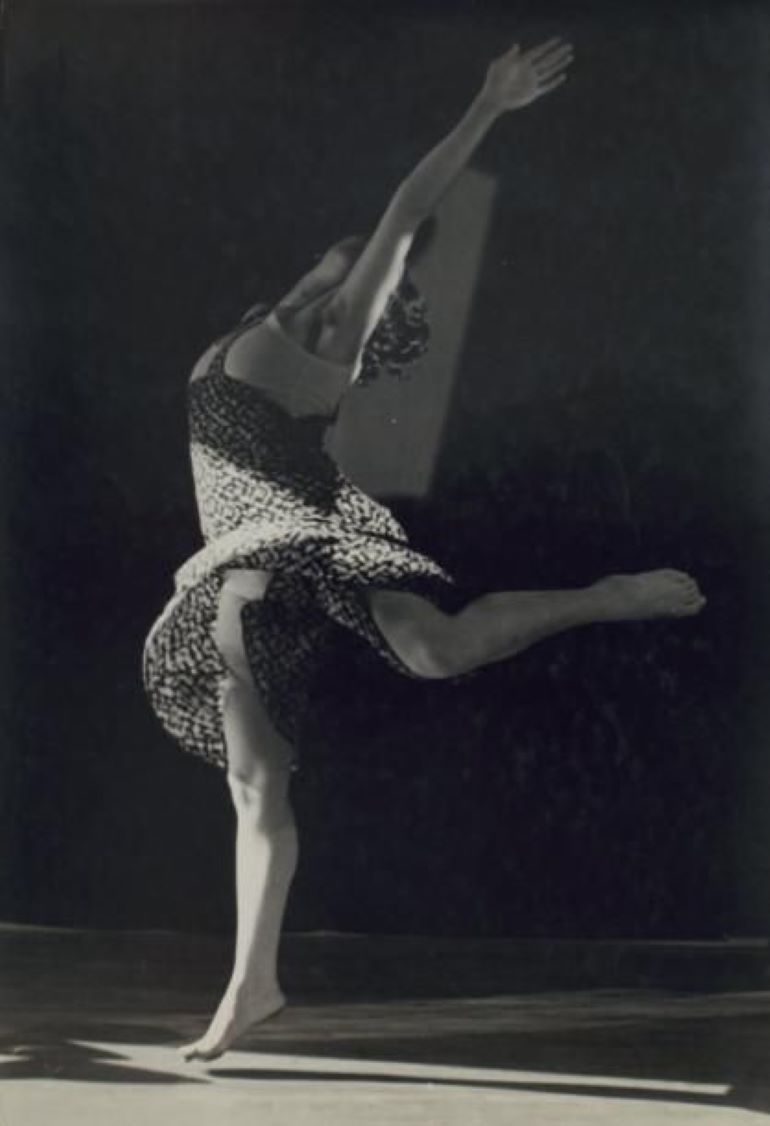

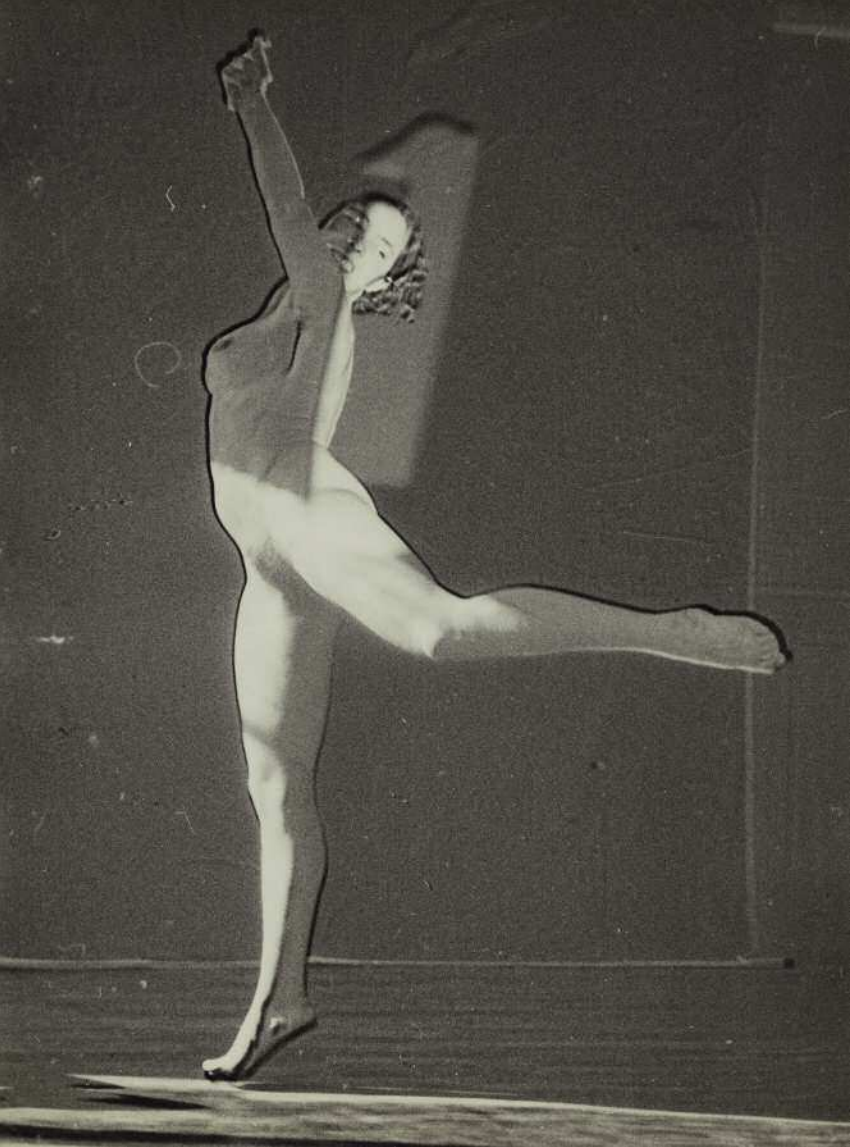

Le domino de lumière (1933) par André Steiner (Andor Steiner)

All images from Binoche et Giquello and Giquello & Associés

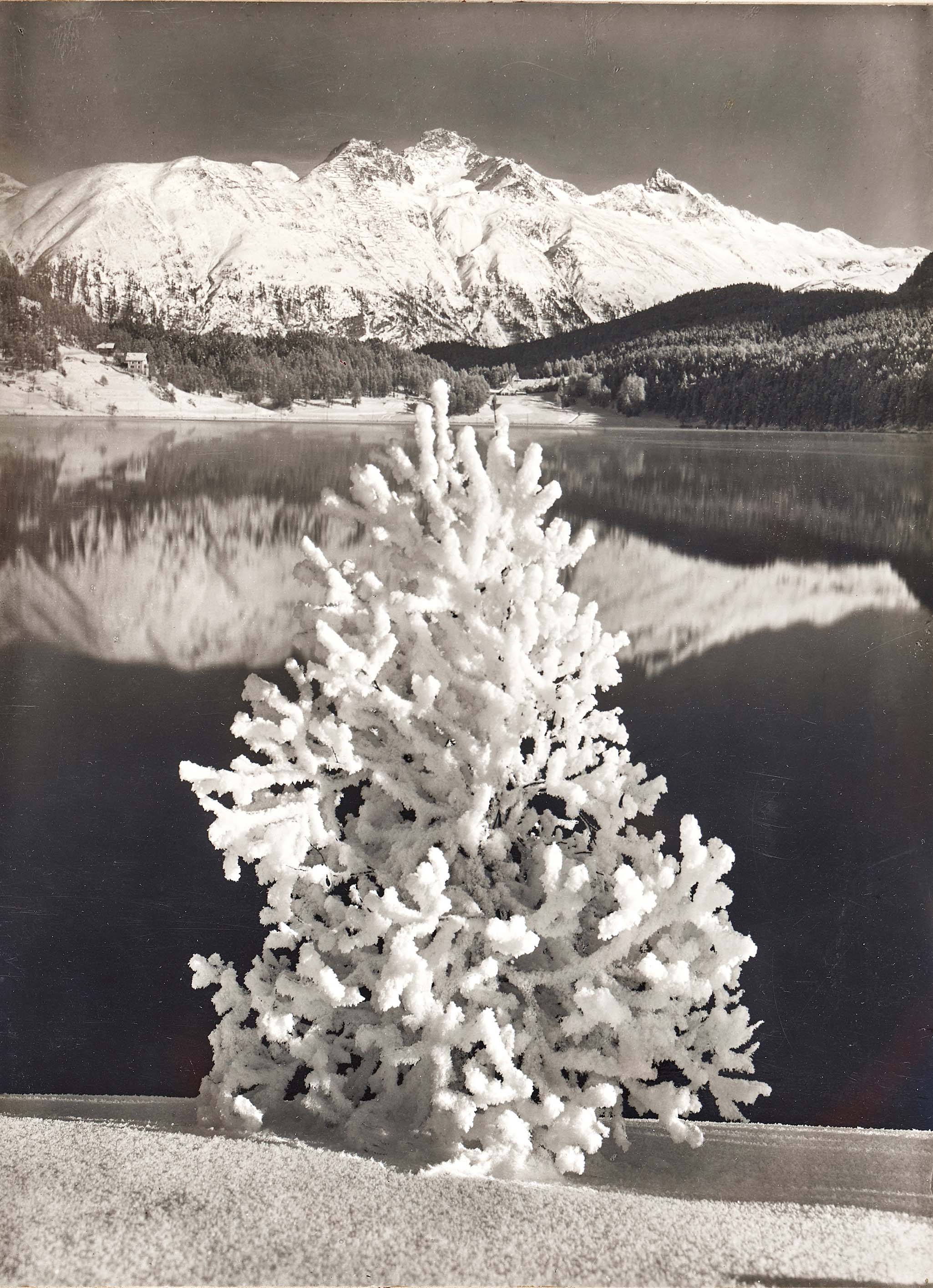

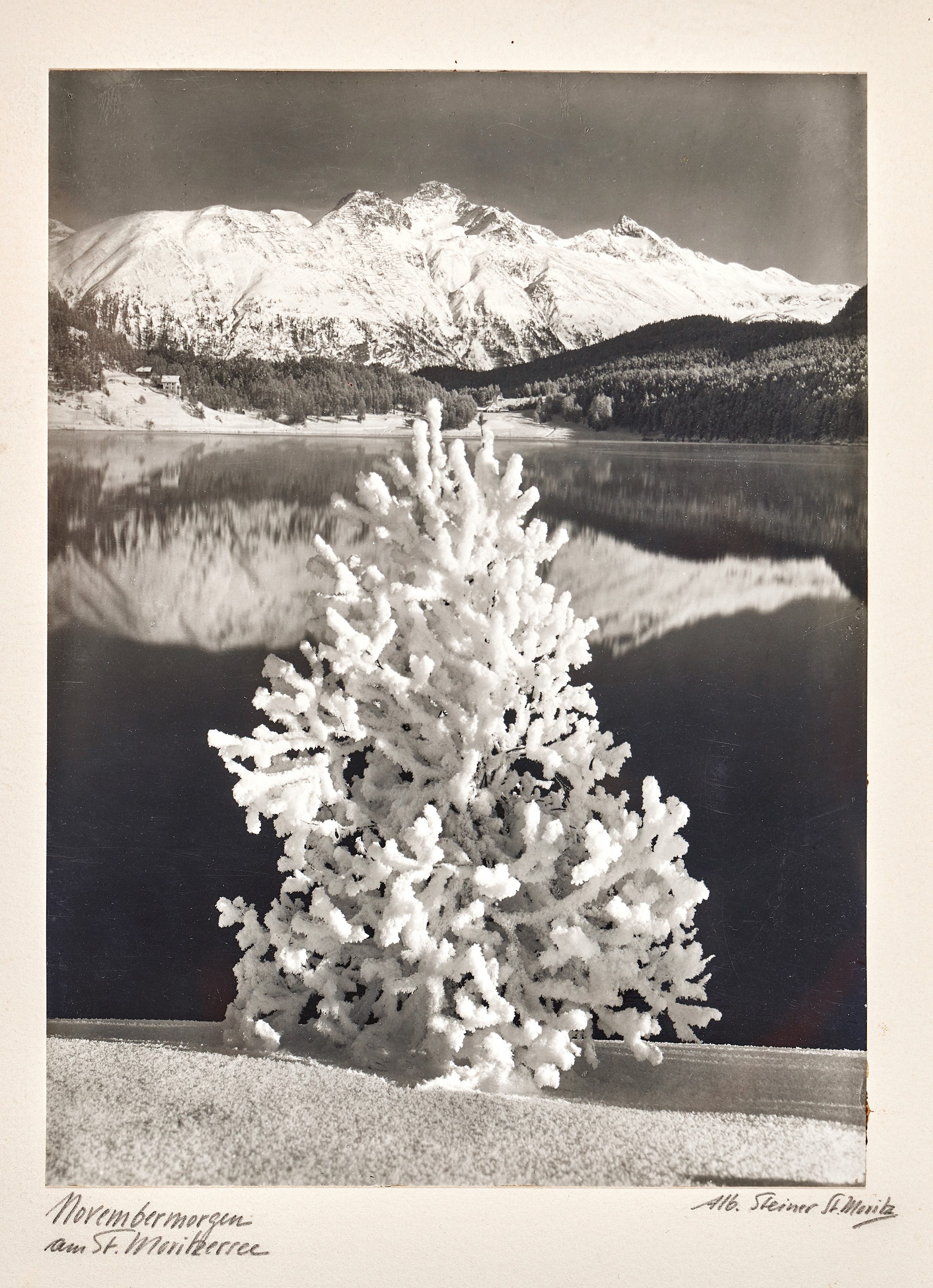

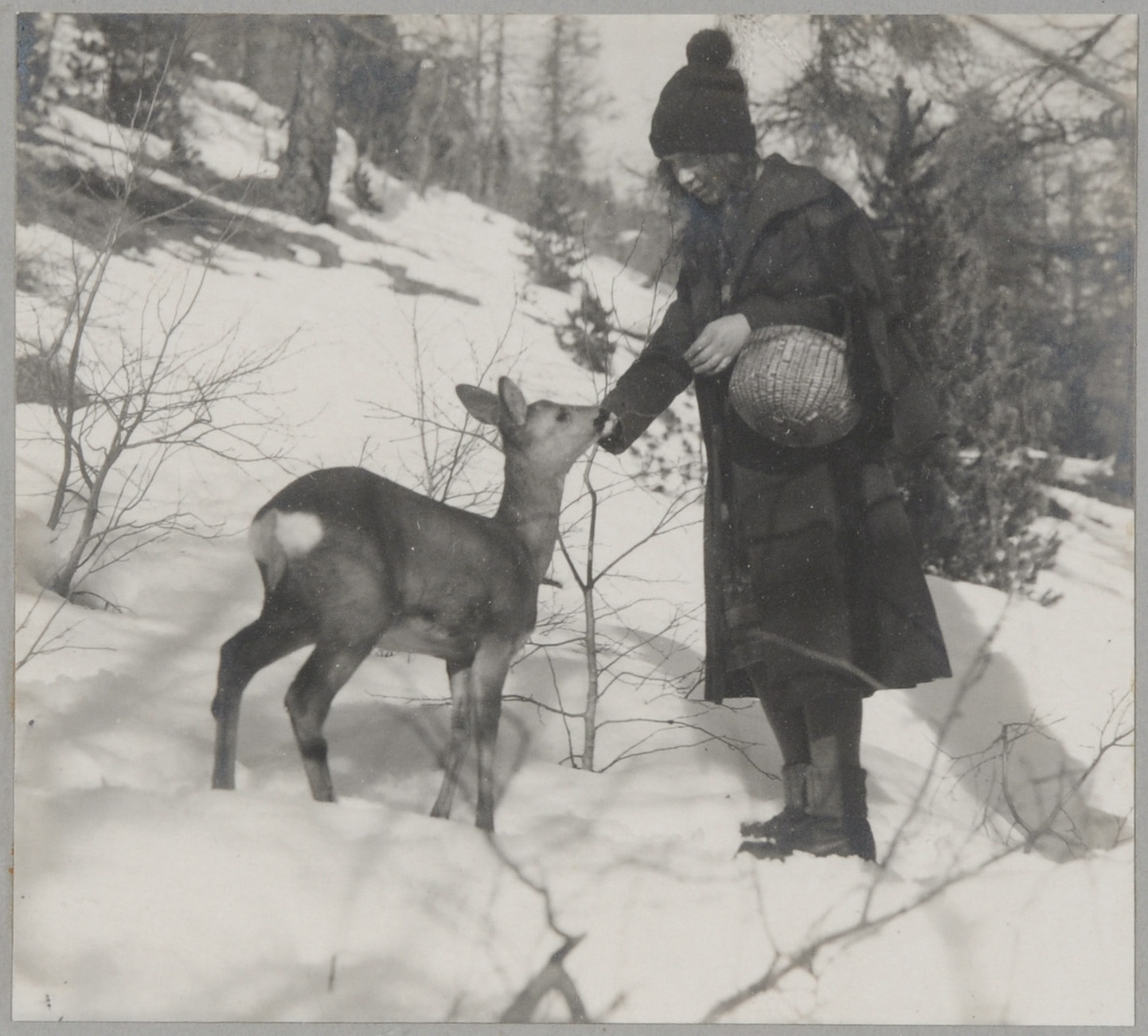

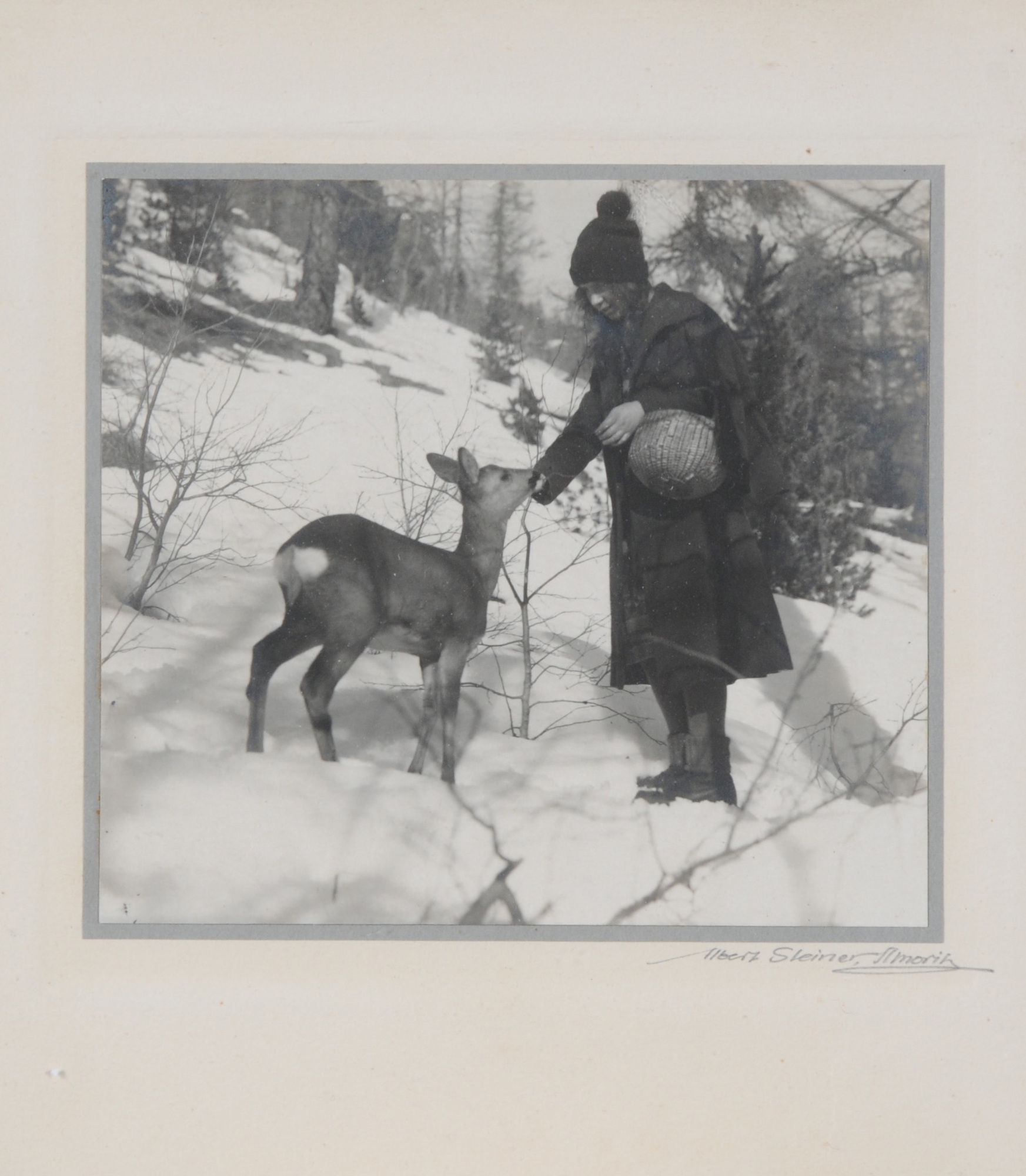

Albert Steiner (1877-1965) is one of Switzerland’s outstanding 20th century photographers. His landscape photographs taken in the Engadine, where he lived and worked for 46 years, are unique on an international as well as a national level. They have had a major influence on an awareness of Switzerland as an unspoiled alpine country of surpassing beauty. Inspired by painters such as Giovanni Segantini and Ferdinand Hodler, Steiner took pictures that reveal a profound respect for and love of nature, as well as a tireless search for timeless beauty and metaphysical truth. His meticulously structured, light-saturated compositions are expressive witnesses of his experience of human insignificance in the face of the greatness and sublimity of the mountain world. Surprisingly, up till now Steiner’s work has not been accorded the appreciation it deserves.

The exhibition “Albert Steiner, the photographic oeuvre”, which comprises around 150 photographs from various public and private collections, represents the first comprehensive overview of Steiner’s work, which reached its peak between 1910 and 1930. It also pays tribute to the different ways in which the photographer interpreted the mountain world. With his almost painterly photographs, associated as they were with pictorialism, he intensified the landscape almost to the point of unreality. With an objective and graphic visual language, his orientation in the 1920s was also based on the principles of the New Objectivity, and it was from this position that he created Switzerland’s first modern photography book (Schnee Winter Sonne, 1930), which may justifiably be compared with Albert Renger-Patzsch’s classic Die Welt ist schön (1928).

The origin of Steiner’s intensive, almost obsessive concern with the mountains was his own independent vision. More than any other Swiss photographer before him, Albert Steiner felt himself to be an artist. And, unlike many of his contemporaries, he regarded photography as a self-evidently appropriate means for creating works of art, an approach that effectively ensured the lasting relevanceof his work. [quoted from Fotostiftung Schweiz]

The New York Public Library hosts a group of around 150 photographs (shot by Vandamm Studio) of the musical The Band Wagon, unfortunately the resolution is very poor as well as the information provided: here is the direct link to them: NYPL/Billy Rose Theater Division/Vandamm theatrical photographs.

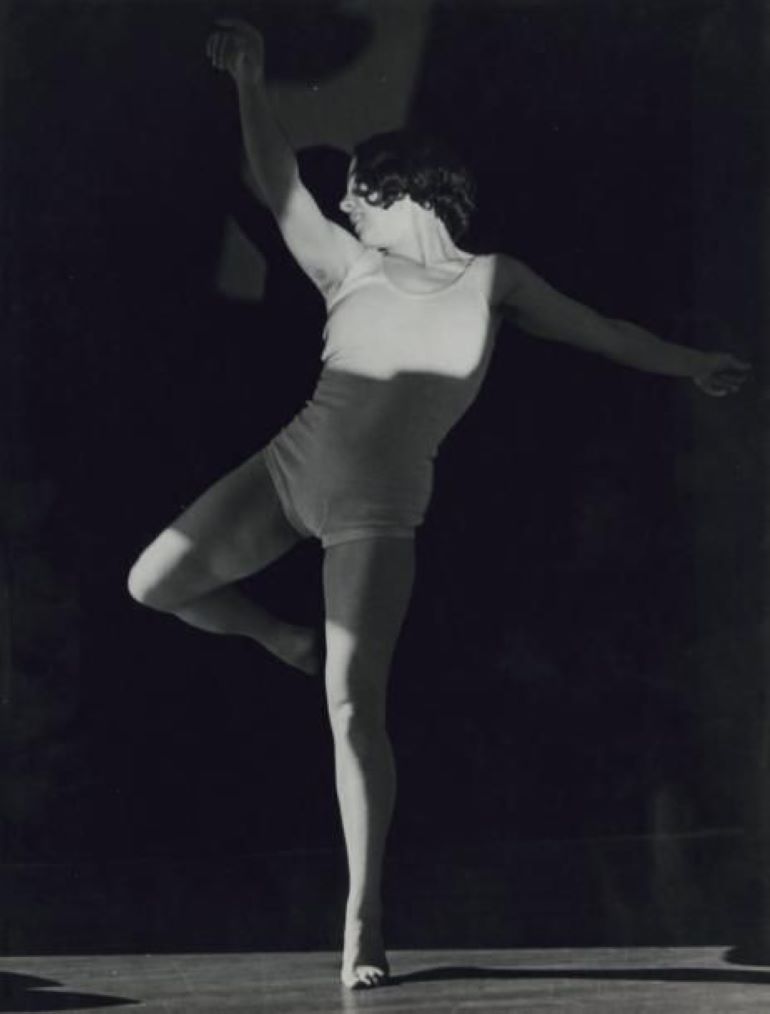

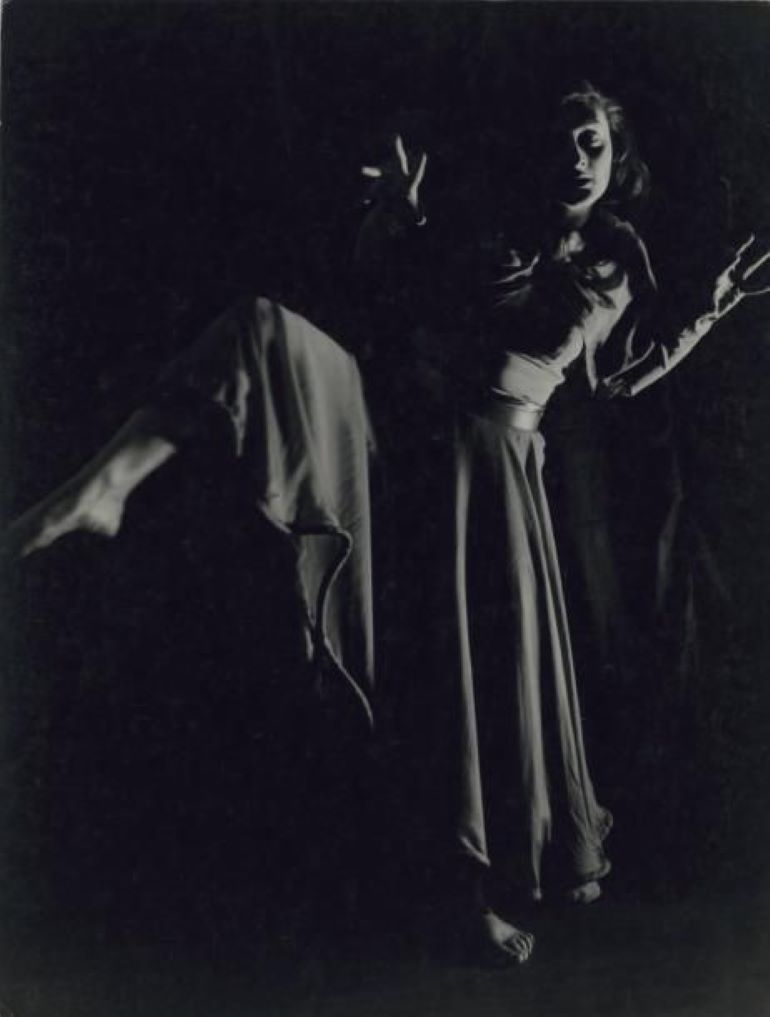

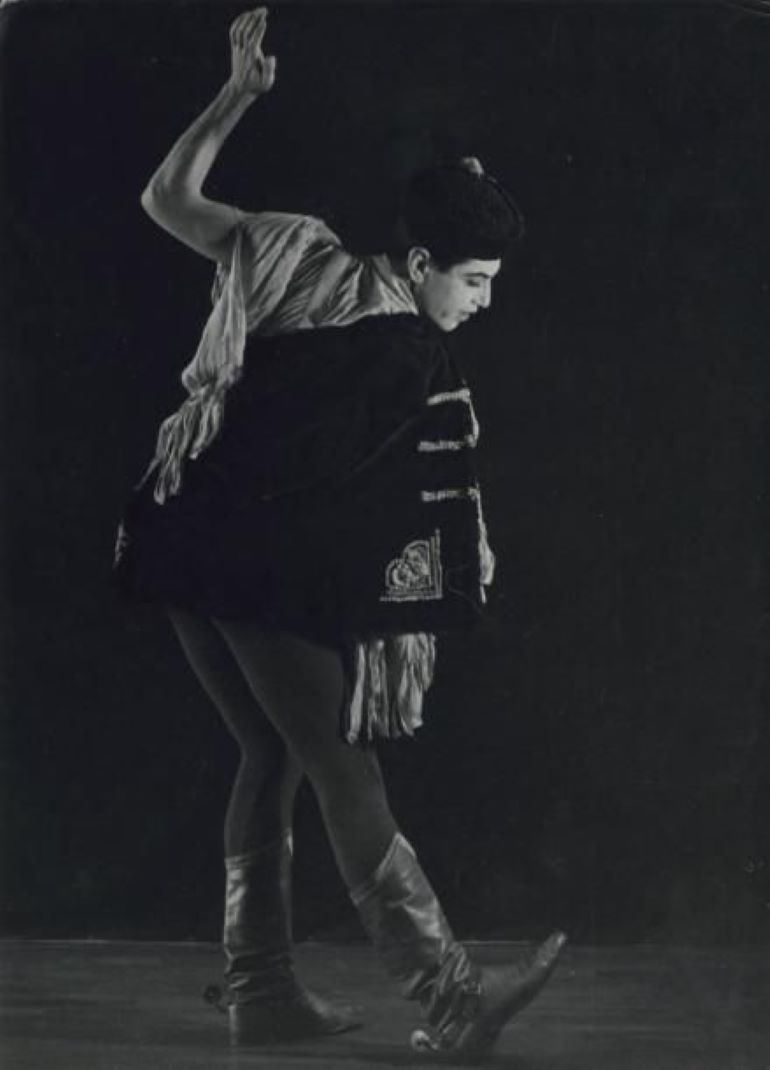

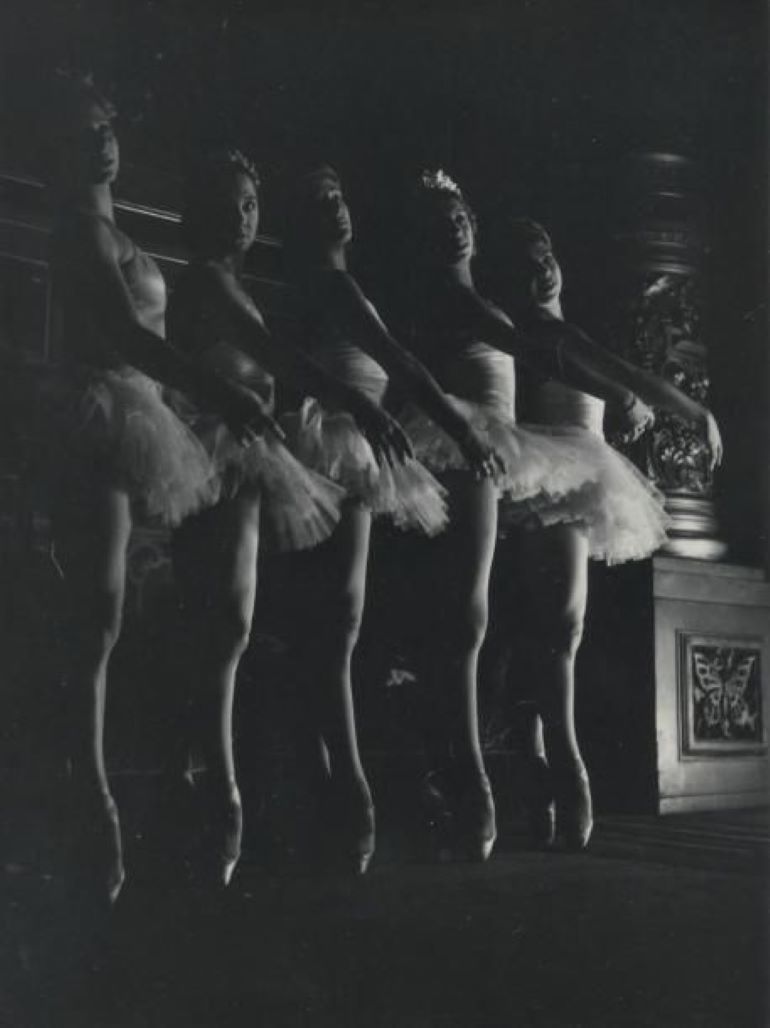

The Band Wagon opened on Broadway at the New Amsterdam Theater on June 3rd, 1931, and concluded on January 16th, 1932, running a total of 260 performances. Produced by Max Gordon, with book by Walter Thomson and Howard Dietz, lyrics also by Dietz and music by Arthur Schwartz. Staging and lighting were by Hassard Short, choreography by Albertina Rasch, and scenic design by Albert R. Johnson. The cast included Fred Astaire, Adele Astaire, Helen Broderick, Tilly Losch, John Barker and Frank Morgan (among others). The show introduced for the first time Schwartz-Dietz’s song Dancing in the Dark (danced by Losch).

Structure of the revue: the musical comedy consisted in five sketches and thirteen songs or musical numbers divided in two acts. As far as we are aware, Losch took part in three of the musical numbers: The Flag, The Beggar Waltz (with Fred Astaire) and Dancing in the Dark (with John Barker).