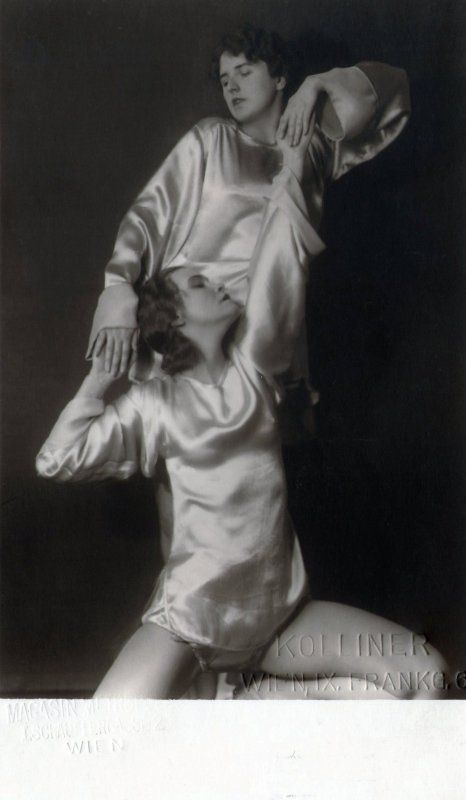

(self) Portrait by Wilding

images that haunt us

This portrait by Cecilia Beaux portrays the artist’s cousin, Sarah Allibone Leavitt, dressed in white with her black cat on her shoulder. Beaux was recognized not only for her bold painting technique, but also for her ability to imbue her female subjects with wit and intelligence, rendering them more than just mere objects of beauty. A student in Paris in the late 1880s, the artist was influenced by her firsthand exposure to French impressionism. Her light-filled palette and gestural style invite comparisons with many of her contemporaries, including William Merritt Chase, James McNeill Whistler, John Singer Sargent, and Mary Cassatt.

The sitter’s white dress, for instance, evokes Whistler’s infamous 1862 painting of Joanna Hiffernan, Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl (National Gallery of Art, Washington). The formal connection between the two paintings demonstrates Beaux’s knowledge of Whistler’s painting. Additionally, the direct gaze of the black cat perched on Sarah’s shoulder references Edouard Manet’s painting Olympia (1865, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), in which a similarly posed black cat sits at the foot of Olympia’s bed. These connections suggest that Beaux intended to reveal more with this portrait than simply her mastery of painting technique. The enigmatic title of the painting may represent Manet’s influence—Beaux’s use of Spanish diminutives, Sarita for Sarah and Sita, meaning “little one,” for the cat, acknowledges the late 19th-century popularity of Spanish painting, championed by Manet.

The present work is a replica of the original painted in 1893 and displayed in the 1895 Society of American Artists exhibition in New York. Before donating the original to the Musée de Luxembourg in Paris (now in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris), Beaux recorded that she made a second painting for her “own satisfaction when the original went to France for good.” / quoted from NGA

Approximately by the time this photo was taken Joseph Stalin was launching his campaign to compel all Soviet artists to observe the rules of ‘socialist realism’. The hunting took a step further and the Meyerhold weren’t the exception. In this new scenario of persecution there was no room for avant-gardists; it did not matter at all that he was one of the first prominent Russian artists to welcome the Bolshevik Revolution.

Reich and Meyerhold married in 1922 after Meyerhold return to Moscow and the foundation of his own theater in 1920, which was known from 1923 to 1938 as the Meyerhold Theatre. In the 1930s the Stimmung became more and more toxic and after Shostakovich had been singled out as being guilty of ‘formalism’, in January 1936, Meyerhold evidently surmised that he would soon be a target, and in March 1936 delivered a talk entitled “Meyer against Meyerholdism”.

A year later, in April 1937, his wife, Zinaida Reich, wrote Stalin a long letter alleging that her husband was the victim of a conspiracy by Trotskyists and former members of the disbanded Russian Association of Proletarian Writers.

In June 1939, Meyerhold was arrested in Leningrad (the 20th). Three weeks later two assailants stabbed Reich to death at the couple’s apartment in Moscow (July 14-15th). The murder is generally regarded as having been organized by the NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs). According to Arkadiy Vaksberg: “Beria needed this sadistic farce” because the actress was extraordinarily popular, independent, outspoken and known for saying: “if Stalin can make no sense of art, let him ask Meyerhold, and he will explain” (Toxic Politics; 2011)

Following his arrest, Meyerhold was taken to NKVD headquarters in Moscow and tortured repeatedly. But it was not until the 1st February 1940 after his “confession” of being a British or Japanese spy that he was sentenced to death by firing squad and executed the next day.

The images of this post are from an earlier, brighter era for the Meyerhold and in the USSR.